Editors' note: This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU debate on euro area reform.

The European fiscal rules were designed some 30 years ago with the primary aim of ensuring sustainable public finances in the Economic and Monetary Union (EMU). One intention was to avoid fiscal profligacy in individual countries spilling over in the form of higher inflation and interest rates. Since then, the economic landscape has changed dramatically. If the secular decline in real interest rates does not reverse, monetary policy can be expected to operate in the vicinity of the effective lower bound (ELB) on interest rates more frequently. In such a situation, as shown in the ECB’s recent strategic review,1 mutual reinforcement of monetary and fiscal policies can ensure a swifter achievement of macroeconomic stabilisation objectives. Concretely, when confronted by persistent inflation undershooting, the effectiveness of monetary policy may depend on the effectiveness of the fiscal framework to facilitate coordinated and efficient fiscal stabilisation. At unchanged policy rates, fiscal multipliers tend to be strong while favourable financing conditions support governments via lower borrowing costs. Therefore, during lasting lower bound episodes, monetary and fiscal policies can mutually create policy space for each other. And vice versa, if domestic inflation is persistently above target, counter-cyclical fiscal policies would ‘lean against the wind’ and help to prevent an overheating of the economy. It is also in this context that an overhaul of the European fiscal rules is considered warranted to achieve a better trade-off between output stabilisation and reductions in governments’ indebtedness.

Our proposal: The basics

In line with numerous contributions to the debate on the reform of the EU’s fiscal rules, in a recent paper (Hauptmeier et al. 2022) we propose a ‘two-tier system’ that links an expenditure rule with a debt anchor (European Fiscal Board 2020, D’Amico et al. 2022).2 Our two-tier approach combines two existing features of the Stability and Growth Pact (SGP) framework, namely, the expenditure benchmark3 as the single operational indicator, which would be linked to the debt anchor, that is, the Treaty debt reference level of 60% of GDP. Compared with the SGP’s status quo application, our system has two major advantages. First, the anchor function can ensure that fiscal adjustment needs are in line with fiscal challenges, i.e. larger for countries with higher government debt. Second, by being less reliant on the annual output gap than the structural balance, an expenditure rule – such as the SGP’s expenditure benchmark – tends to have better counter-cyclical properties.

Specifically, our proposal consists of three elements:

- First, we suggest maintaining the Treaty’s 60% of GDP debt reference value to act as an anchor in a ‘two-tier system’. We consider a change in the debt reference value to be politically difficult. Moreover, we are of the view that countries with debt-to-GDP ratios safely below 60% possess fiscal space, especially in times of contained interest–growth differentials. This can be used for additional government investment – for example, for the pressing need to mitigate climate change.

- Second, we propose tailoring the SGP’s expenditure benchmark to the debt anchor, while allowing for a slower pace towards it than currently foreseen under the SGP’s debt rule. As argued, for example, by the European Fiscal Board (2020) and Hauptmeier and Kamps (2022), the current speed of debt adjustment required by the SGP’s 1/20th rule appears overly demanding for high-debt countries. We suggest reducing the speed towards the debt anchor through (i) lowering the 1/20th or 5% adjustment requirement to 3%; and (ii) similar to D’Amico et al. (2022), a longer-term smoothing of adjustment requirements towards the debt anchor (nine-year forward-looking). The current rule targets average adjustments over three years. By lowering the general adjustment speed towards the debt anchor, we avoid the complexity of the proposal by D’Amico et al., who define different adjustment requirements for certain types of debt (notably, a lower speed of adjustment, inter alia, for crisis- and investment-related debt issuance). We believe that such differentiated adjustment not only adds complexity but would also face political resistance. At the same time, our proposed reduction in the general adjustment speed would have similar implications in terms of debt reduction, notably for high-debt countries (considering the simulations shown in Giavazzi et al. 2021).

- Third, we suggest accounting for the ECB’s symmetric inflation target by replacing the national GDP deflator in the current definition of the expenditure benchmark with a fixed nominal growth component of 2% (see also Lane 2021).4 Currently, the GDP deflator is used as a measure of inflation to convert the real benchmark growth rate into nominal terms so that it can be compared to the change in the expenditure aggregate. Replacing the GDP deflator growth rate with the constant 2% inflation objective, as we propose, can further reduce the pro-cyclicality in the fiscal response to nominal shocks that is present in the current framework for two reasons. First, in times of declining (increasing) domestic inflation (as measured by the growth rate of the GDP deflator), the excess of debt over the debt anchor rises (declines), making adjustment needs under the fiscal rule more (less) demanding. Second, in times of lower (higher) domestic inflation, the current definition of the SGP’s expenditure benchmark allows for lower (higher) spending growth. The proposed parametric adjustment would also improve the counter-cyclicality of the framework by automatically increasing fiscal space in times of inflation below the target, and vice versa. This would facilitate the synchronisation of fiscal and monetary policy over the cycle.

It is important to stress that, in our proposal, the inflation-adjustment of the expenditure rule is based on the growth rate of the GDP deflator rather than HICP inflation. The GDP deflator constitutes a broad indicator of underlying domestic price developments (including in the public sector) and is typically less volatile than HICP, given that, for example, it is less affected by import price developments. Recently, this latter aspect has become important in a context of volatile and high commodity prices related to an exogenous supply shock, with the GDP deflator remaining markedly below HICP. Only over longer periods do the HICP and the GDP deflator show similar average inflation. Consequently, our fiscal policy rule provides for stability especially in the presence of demand shocks, but also shields from undue adjustment when economies are affected by exogenous supply shocks that shift inflation beyond the ECB’s target.

Simulation results

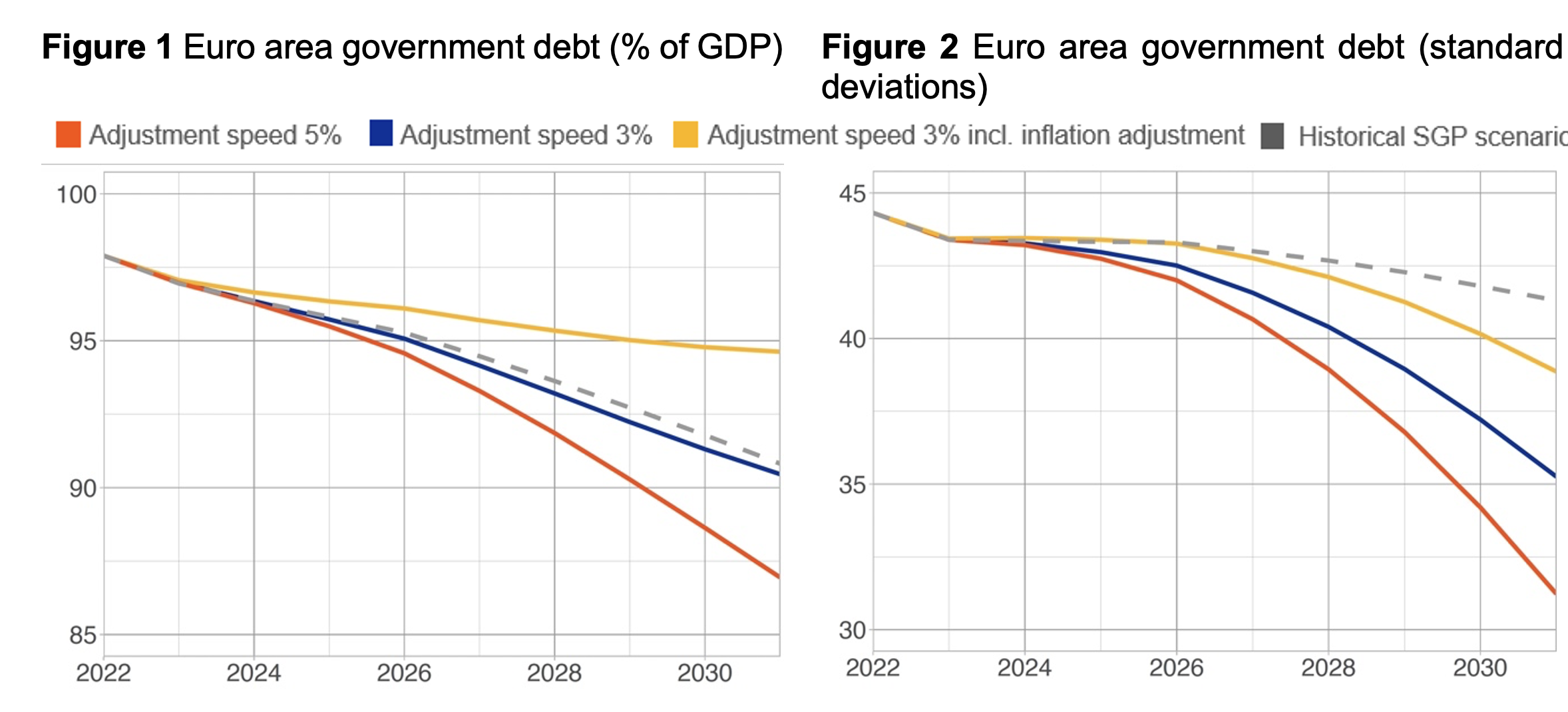

Figure 1 shows the simulated debt reduction paths for the euro area on aggregate that follow from the application of our suggested fiscal rule. They derive from a computed constant growth rate of government expenditure under the expenditure benchmark which, if implemented as of 2023, would ensure that the intermediate debt target is met at the end of the simulation horizon (i.e. in 2031). The currently applied SGP status quo serves as a benchmark.5 As can be seen from the figure, the current adjustment speed under the SGP’s debt rule would imply a gradual reduction of the euro area aggregate debt ratio by around 10 percentage points of GDP from somewhat below 100% of GDP to below 90% of GDP.

Figure 2 shows that the application of the debt rule in its current parametrisation would significantly reduce the heterogeneity in debt ratios (as measured by the standard deviation). This results from the fact that high-debt countries would need to ensure a more significant reduction in their debt-to-GDP ratios, given that the adjustment parameter links to the distance to the 60% of GDP debt reference level. Lowering the speed of adjustment under the debt rule from 5% to 3% would ensure a more gradual but politically and economically more feasible debt adjustment. Still, the aggregate debt ratio would decline to around 90% of GDP over the simulation horizon with a decline in the standard deviation to 35% of GDP (from just below 45% of GDP currently).

Based on the European Commission’s 2021 Autumn forecast,6 which projected a drop of inflation (as measured by the growth rate of the GDP deflator) to below 2% as of 2023, the application of an inflation-adjusted expenditure growth rule would reduce adjustment requirements compared to the case of a non-adjusted rule for the euro area on average. Conceptually, positive (negative) gaps vis-à-vis the inflation target increase (decrease) the allowed growth rate of spending under the rule.

Sources: European Commission Autumn 2021 Economic Forecast, own calculations.

Notes: As of 2024, fiscal and macroeconomic assumptions are in line with the European Commission’s 2020 Debt Sustainability Monitor. The latest T+10 assumptions for potential GDP growth rates needed for the computation of the expenditure benchmark are taken from the Output Gap Working Group of the Economic Policy Committee. The macroeconomic impact of fiscal adjustments required by the fiscal rule is incorporated on the basis of dynamic fiscal multipliers based on the so-called Basic Model Elasticities (BMEs), developed within the Eurosystem and based on the forecasting models in use in the national central banks. See Hauptmeier et al. (2022) for further details.

Two final remarks on the implications of a persistent shock to the baseline path for domestic inflation (as measured by the GDP deflator). The debt rule in its current specification with a 5% speed of adjustment would imply a pro-cyclical fiscal response to nominal shocks. Concretely, a decline (increase) in domestic inflation triggers an increase (decline) in the fiscal adjustment required under the rule. In contrast, an inflation-adjusted debt rule would react counter-cyclically as adjustment requirements drop with a decline in inflation and vice versa. Obviously, in case of a permanent shock to inflation, the corresponding implications for government debt trajectories relative to the baseline would be more pronounced than in the presence of just a temporary shock.

Conclusion

The two-tier framework we propose, which combines a lower speed of debt adjustment with an explicit accounting for the ECB’s 2% inflation objective, would help to better account for macroeconomic conditions while also supporting a gradual phasing-in of the necessary fiscal adjustment to address debt overhangs in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. Being a relatively ‘surgical’ parametric adjustment of the existing SGP framework, we argue that our proposal internalises political and legal feasibility considerations as well as fundamental economic concerns with the current fiscal rules. It arguably retains elements of complexity. Still, we consider that our proposal provides a conceptual framework that overall would ensure more transparency and consistency across countries than currently is the case, thus supporting multilateral surveillance. It could be implemented on the basis of the current institutional and governance structure of the European fiscal framework. It would replace the current 1/20th rule of the SGP while keeping the 3% deficit threshold in place. Possible excessive deficit procedures could be calibrated in line with the proposed debt reduction under our two-tier setup.

It is important to note that taking account of the ECB’s 2% inflation target in the spending rule should not be seen as a subordination of fiscal policy to the ECB’s monetary policy. Applying an inflation-adjusted expenditure growth rule achieves an automatic – not fine-tuned – counter-cyclical modulation of adjustment requirements in the face of nominal shocks, i.e. fiscal space is created when inflation is low while the rule becomes more constraining when inflation is above target.

Authors’ note: We thank Oscar Arce, Philip Lane, Klaus Masuch and Jean Pisani-Ferry for helpful comments and suggestions.

References

Claeys, G, Z Darvas and A Leandro (2016), “A proposal to revive the European fiscal framework”, Bruegel Policy Brief 2016/07.

D'Amico, L, F Giavazzi, V Guerrieri, G Lorenzoni and C-H Weymuller (2022), “Revising the European fiscal framework, part 1: Rules”, VoxEU.org, 14 January.

European Fiscal Board (2020), Rethinking the EU Fiscal Rules, EFB Annual Report, Brussels.

Hauptmeier, S and C Kamps (2022), “Debt rule design in theory and practice: the SGP’s debt benchmark revisited”, European Journal of Political Economy, forthcoming.

Hauptmeier, S, N Leiner-Killinger, P Muggenthaler and S Haroutunian (2022), “Post-Covid Fiscal Rules: A Central Bank Perspective”, ECB Working Paper No. 2656.

Lane, P (2021), “The future of the EU fiscal governance framework: a macroeconomic perspective”, panel at the European Commission webinar on “The future of the EU fiscal governance framework”, 12 November.

Endnotes

1 https://www.ecb.europa.eu/home/search/review/html/index.en.html

2 See also Hauptmeier and Kamps (2022).

3 The so-called expenditure benchmark was introduced in the preventive arm of the SGP in the context of the 2011 reform. The basic idea of this indicator is to compare the growth rate of government expenditure (net of discretionary tax measures, cyclical spending and transfers from EU budget) with a benchmark rate of medium-term potential GDP growth.

4 Claeys et al. (2016) have proposed a similar parametric adjustment of the SGP’s expenditure benchmark indicator.

5 Countries with deficits above 3% of GDP implement a structural adjustment in line with the average observed under historical EDP procedures. In case of a deficit ratio below 3% broad compliance with the requirements of the preventive arm of the SGP is deemed sufficient. In both cases, the average annual adjustment speed amounts to around

6 We use the Commission’s Autumn 2021 forecast since it is the latest available fully-fledged fiscal and macroeconomic forecast.