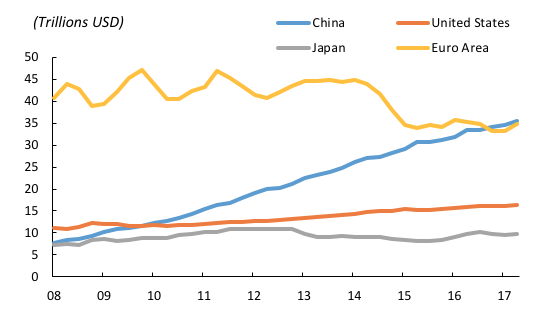

China’s banking system has been growing steadily over the past eight years. Measured in total assets, its size surpassed that of the US banking system in 2010, and even all euro area banking systems put together in the last quarter of 2016 (see Figure 1). It is now clearly the largest banking system in the world, with $35 trillion in total assets (about 300% of China’s GDP).1

Figure 1 Total bank assets for selected countries

Source: Bank of Japan, CEIC, European Central Bank, FRED.

Domestic versus foreign operations

Domestic assets constitute most of Chinese banks’ balance sheets, representing about 97% in 2016 based on aggregate official data. Behind the very fast growth in domestic assets, as highlighted in IMF (2017), there is a lending boom that resulted from (among other things) a focus on hitting GDP growth targets and protecting employment while China is transitioning from a high-growth economic model based on exports and investment to one based on services and consumption.

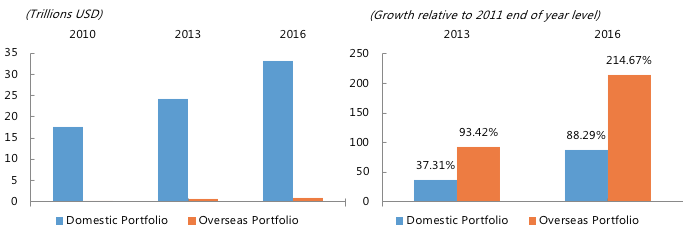

Although relatively small vis-à-vis domestic assets, the size of Chinese foreign claims has been growing at an even faster rate than domestic exposures. For example, as shown in Figure 2, foreign assets have grown more than 200% from their 2011 level, substantially increasing their upward pace with respect to domestic growth in the past three years. Given this context, the rest of the column will focus on Chinese banks’ foreign assets.

Figure 2 Total assets of banks in China, by portfolio type

Source: CEIC, Authors’ calculation.

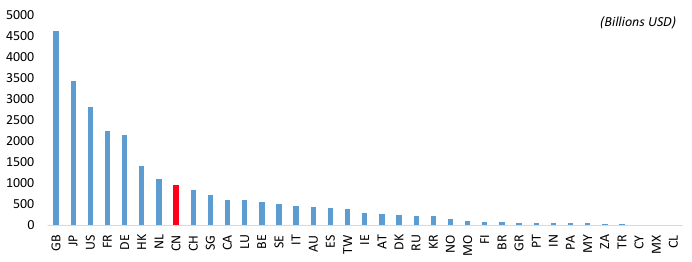

High financial dependence on Chinese banks

One of the recent upgrades to the Bank for International Settlements’ (BIS) banking statistics is an enlargement in the set of reporting countries. With China recently joining the BIS Locational Banking Statistics, it is now possible to have a relatively consistent look at China’s cross-border bank lending. As shown in Figure 3, mainland Chinese banks’ cross-border claims amounted to $970 billion as of the second quarter of 2017, ranking eighth overall globally and exceeding those of traditional financial centres such as Switzerland and Luxembourg, or countries hosting large international banking groups such as Spain and Italy.

Figure 3 Cross-border claims of BIS reporting countries, 2017Q2

Source: BIS.

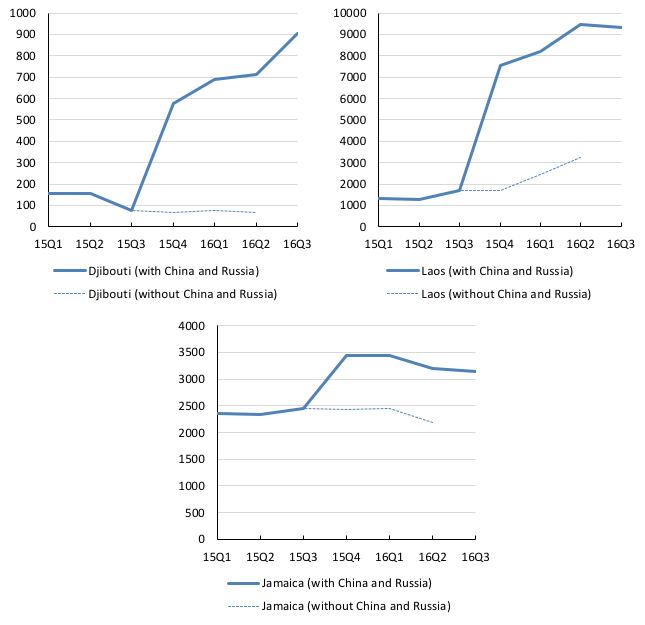

While the BIS does not publicly release China’s bilateral exposures to individual counterparties, we approximate the bilateral linkages by comparing two vintages of aggregate total banks’ claims from the BIS Locational Banking Statistics dataset.2 One vintage was retrieved on 17 October 2016, weeks before it was replaced with a new vintage of the same publicly available data, but now including Chinese and Russian bank data (we retrieved it on 19 January 2017). As shown in Figure 4, the inclusion of China and Russia triggered sharp increases in banks’ claims. For example, BIS reporting of banks’ claims on Djibouti jumped by $650 million (an almost tenfold increase) in 2016Q2. To deal with the issue that Russia and China were included simultaneously in the dataset, we exclude in the rest of the analysis former Soviet Union countries, Cyprus, and Malta (the last two being offshore financial centers), which together account for around half of the total claims by Russian banks. The remaining Russian banks’ claims are distributed across the other countries, but likely concentrated in the US, the UK, and other developed countries (Koon Goh and Pradhan 2016). Thus, our estimates are probably a good proxy for China’s cross-border claims to emerging and developing counterparties.

Figure 4 BIS reporting countries’ claims on selected countries, US$ millions

Source: BIS.

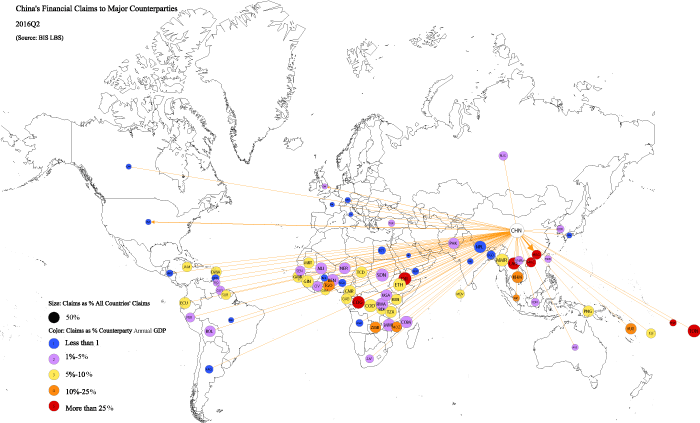

These estimates are plotted in Figure 5, which illustrates the map of Chinese banks’ major financial linkages, by displaying counterparties in the map if either they are G20 countries, or if China’s claims on the node exceed 5% of BIS reporting countries’ total claims on the same node. Not only is China connected to many countries, Chinese banks also serve as major foreign creditors for many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Caribbean, and Southeast Asia (illustrated by node ball sizes above 50% in Figure 5). China’s overseas presence in the global banking network not only throws light on the expansion of China’s banking system, it also highlights the potential spillovers from China to the borrowing countries. In some cases, the claims of banks located in mainland China exceed 25% of counterparty GDP (e.g. Hong Kong, Laos, Congo, and Djibouti).

What can explain the banking relationships? The roles of FDI and trade linkages

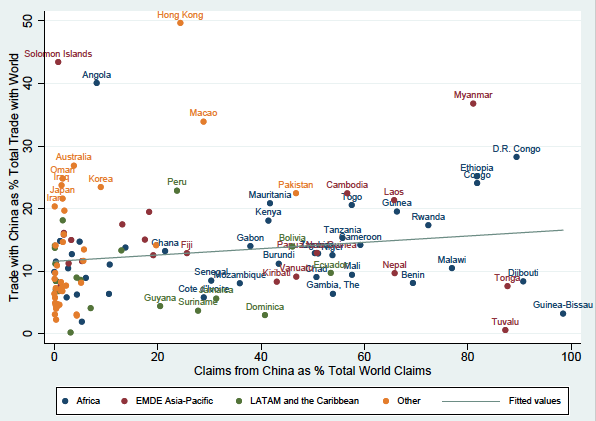

While trade finance motives may explain China’s banking linkages, the financial connections go far beyond what trade can explain. Figure 6 compares the cross-sectional relationship between countries’ gross trade with China in 2016 (as a share of trade with the world) and China’s share of banking claims on them in the second quarter of 2016. Gross trade is defined as gross exports plus gross imports. Overall, no relationship between trade and banking linkages with China is apparent. China’s trade and international banking, although related, are not necessarily different sides of the same coin. For a significant number of African and emerging and developing Asian countries, Chinese banks seem to be the major lenders, even though China has not yet established itself as a major trade partner with these countries.

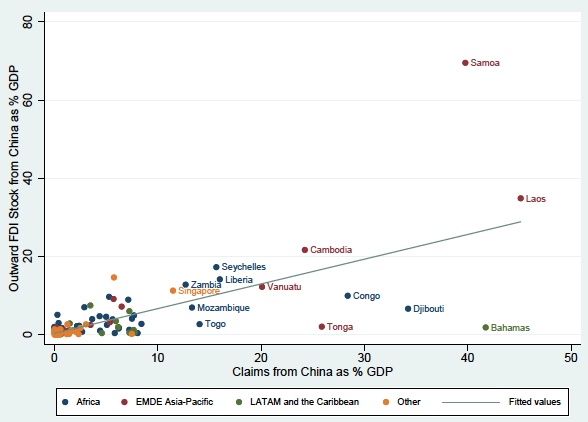

Instead, China’s cross-border lending seems to be more synchronised with its outward FDI. Overseas lending from Chinese banks has been used to fund the construction of large-scale infrastructure projects, such as the hydropower station in Laos, supported by the $1.3 billion loan from China Construction Bank (Yap 2017). Using BIS Locational Banking Statistics and CEIC data, Figure 7 presents the cross-sectional relationship between China’s bilateral FDI stocks and bank claims, both expressed as percentages of recipient GDP. Indeed, the amount of cumulative FDI tends to be large when China has a large bilateral exposure on cross-border lending.3

Figure 5 Importance of China as a counterparty, 2016Q2

Source: BIS, authors’ calculations

Figure 6 Banking and trade linkages with China, 2016

Source: BIS, Direction of Trade Statistics, authors’ calculation.

Figure 7 Banking and outward FDI linkages with China, 2016

Notes: Outliers are excluded to facilitate visualisation.

Source: BIS, CEIC, authors’ calculations.

Policy conclusions

China’s overseas presence in the global banking system is a key feature of the country’s banking system, but it also highlights the potential for financial spillovers from China. From the borrowers’ side, the large relative estimated size of Chinese banks’ claims on several emerging and developing borrower countries highlights that potential spillovers from China depend on direct banking channels together with other traditional channels – such as trade linkages and China’s monopsony power over global commodity prices (IMF 2016).

A better understanding of Chinese banking claims might also help to explain other phenomena – for example, the current low incidence of emerging market and developing country sovereign defaults despite heavy recent external borrowing could be partly associated with mismeasurement (e.g. as information on defaults and/or arrears on Chinese loans is not available). Carmen Reinhart raised this issue recently (Reinhart 2017). We cannot directly address this, but estimating Chinese banks’ bilateral exposures is a first step to a better understanding of global banking linkages and the increasing importance of China.

Authors’ note: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and should not be attributed to the IMF, its Executive Board, or its management.

References

BIS (2016), Quarterly Review, December.

IMF (2016), “Spillovers from China’s transition and from migration”, October 2016 WEO, Chapter 4.

IMF (2017), “People’s Republic of China: Financial System Stability Assessment”, Country report No 17/358

Koon Goh, S and S-K Pradhan (2016), “China and Russia join the BIS locational banking statistics”, BIS Quarterly Review, December.

Reinhart, C (2017), “The curious case of the missing defaults”, Project Syndicate.

Yap, C-W (2017), “Chinese banks ramp up overseas loans”, Wall Street Journal, 9 April.

Endnotes

[1] Following the traditional locational definition, throughout this column the reference to the Chinese banking system corresponds to banks operating from mainland China, independently of the nationality of their owners. Having said this, a large majority of the Chinese banking system is domestically owned. The mainland affiliates of foreign-controlled banks owned only about 1.25% of the banking system’s total assets. In this context, and given that China is not an offshore centre, the identified claims from Chinese banks do not represent important indirect claims from other banking systems, especially in the case of emerging and developing countries.

[2] China and Russia both joined BIS Locational Banking Statistics as reporting countries in November 2016, and reported aggregate claims starting from 2015Q4 (BIS 2016).

[3] This correlation is probably consistent with the ‘going global’ strategy promoted by the Chinese government. The relationship may be even stronger as the ‘One Belt One Road’ initiative unfolds.