Italy is currently the epicentre of the Covid-19 pandemic with 6,820 deaths (as of 24 March). The case fatality rate (CFR) – i.e. the number of deaths over number of reported cases – in Italy is the highest in the world at 9%, according to official statistics (last observation on 21 March).

A recent paper by Bayer and Kuhn (2020) investigates the possibility that the Italian social structure is a key factor in explaining the high mortality in Italy. According to the authors, the elderly in Italy are more exposed to infection because of a higher vertical social integration with respect to other countries. In order to examine whether the Italian social structure favours the diffusion of the virus, the authors look at CFRs across countries with at least 200 COVID-19 infections as the dependent variable and the share of population 30-49 living with their parents (from the World Values Survey 2010-2014) as the main explanatory variable. Using a sample of 24 countries, they find a positive correlation between their measure of vertical social integration and the CFR. They derive some policy implications on social distancing, such as not having grandparents step in as caretakers for children. In drawing these policy implications, the authors implicitly attribute a causal interpretation to the correlation between vertical social integration and fatality rate.

We believe this kind of contribution does not help the advancement of our knowledge of the epidemic. A regression of fatality rates on measures of vertical social integration across 24 countries does not prove causation, and therefore it should not inform any policy recommendation. In their regression, there are a number of omitted variables that can potentially influence the fatality rate and are likely correlated with vertical social integration measures.

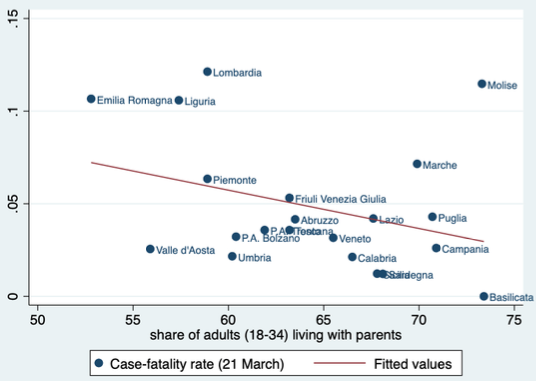

To emphasise this point, we ran the same regression used by the authors (CFRs on measures of vertical social integration) for the 20 Italian regions. If the cross-country correlation found by Bayer and Kuhn underlies a causal relationship, we should observe the same positive sign when we use variation within Italy. The advantage of considering variation within the country is that it allows keeping constant (to a certain degree) variables such as institutions, the healthcare system, and lifestyles (the heterogeneity of which is much more substantial across countries and cannot be ignored). Data for the vertical social integration measure (i.e. the share of adults aged 18-34 living with their parents) are taken from Istat (2019 wave) and case fatality rates are taken from the Civil Protection Department.

Figure 1 clearly shows that the correlation across Italian regions is negative. Interestingly, this correlation is always negative if we vary the day on which we compute the fatality rate and results turn out to be statistically significant for some days and not statistically significant for some other days. The sign of the correlation remains negative even when we consider alternative measures of vertical social integration. In other words, the relationship across regions has an opposite sign to the relationship across countries. In any event, neither of them can be attributed a causal interpretation, for the reasons explained above.

Figure 1 Correlation between the case-fatality rate and an index of vertical social integration across Italian regions

In addition, the cross-country analysis in Bayer and Kuhn (2020) pools together countries that are at different stages of their epidemic curve and that apply different standards for testing and reporting positive cases and deaths from Covid-19. These measurement issues make their cross-country comparison meaningless.

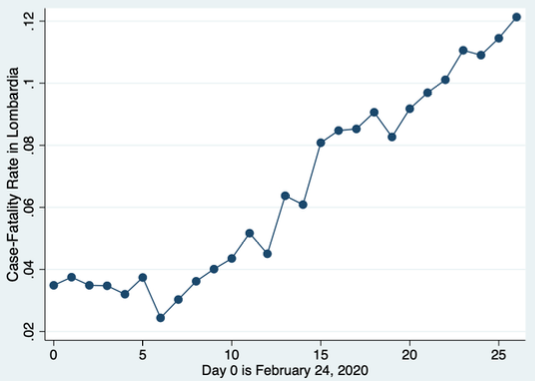

We believe that a crucial object of analysis should be the infection fatality rate (IFR) (number of deaths over the sum of total cases, reported and unreported). Clearly, the CFR is correlated with the IFR, but it is several magnitudes higher since we do not know the number of unreported cases. The heterogeneity across space between the IFR and CFR ratio is unknown and possibly evolves along different phases of the epidemic. Using the CFR as a proxy for the infection fatality rate is flawed, especially for countries that are at different stages of their epidemic curve. The CFR, especially in northern Italian regions, has steadily increased since the day on which Italy started to test only people with symptoms of Covid-19 (March 1, 2020). Figure 2 below reports the evolution of the CFR for the region that is suffering the most from the Covid-19, Lombardy, since the beginning of the epidemic. As we can see, the CFR has increased steadily since day 7 (2 March 2020), a period when the healthcare units were not yet congested. This is another indication that, in our studies on this subject in Italy, the CFR is not very informative on the IFR, which is expected instead to move more smoothly over time.

Figure 2 Case fatality rate in Lombardy since 24 February 2020

Related to this this point, the comparison of CFRs across countries might also be problematic for reasons related to the numerator (i.e. the number of deaths). The classification of cause of death may vary across countries due to different classification approaches adopted or the different healthcare systems. For instance, in the majority of cases of death from COVID-19 in Italy, other pre-existing chronic pathologies were present at the time of the infection (the average number of concomitant pathologies among the deceased subjects is 2.7). It is not obvious that all European countries classify deaths due to Covid-19 in the same way when the deceased suffered from other pre-existing concomitant pathologies.

For these reasons, the results in Bayer and Kuhn (2020) should be taken with caution, at least until they undergo a serious peer-review process. However, the paper has already received extensive media coverage in Italy and could potentially influence the heated policy debate about potential policy responses to COVID-19. This example makes it clear the visibility that our work can have in this dramatic historical period and the responsibility that comes with this.

We need to mobilise scholars with expertise in public policy evaluation, network analysis, and epidemiology to understand the complex dynamics behind the epidemic and to assess the effectiveness of alternative policies. To do this, it is crucial to harmonise data and methodologies of data collection on deaths, at least across European countries. Whenever possible, all available microdata on the outcome of tests, deaths, and hospitalised patients should be made publicly available. The disaster we are experiencing is a global one and requires an unprecedented effort from the academic side. The effort to move quickly is commendable; however, it can come with the risk of suggesting ineffective policy recommendations that, in a period of crisis, can result in higher costs than benefits.

References

Bayer, C and M Kuhn (2020), “Intergenerational ties and case fatality rates: A cross country analysis”, CEPR Discussion Paper no. 14519.