Picture yourself strolling through the hallways of a 1950s American high school. The scene is a sea of conformity: boys with crew cuts, many sporting jackets and ties, while girls don demure dresses and perfectly coiffed hairdos. Fast forward to today, and you be greeted by a kaleidoscope of colours, hairstyles, and fashion choices that would make your head spin. This stark contrast serves as a potent reminder that culture is far more than just a set of beliefs and attitudes – it's a way of life, constantly evolving and shaping society.

Recent years have seen considerable progress in analysing culture as a ‘way of life’, using data on consumption patterns, folklore, and naming patterns (Bazzi et al. 2020, Michalopoulos and Xue 2021, Atkin 2016). To analyse style choices as a key dimension of culture, we need two things – data, and a way to make them speak. In our study (Voth and Yanagizawa-Drott 2024), we use portrait photos of high school seniors in the US, 1950-2010, to track cultural change. The idea of using photographs as a window into social trends is not new. Francis Galton, the Victorian polymath, infamously used composite images to create 'archetypal' faces of criminals and prostitutes (Galton 1878). Thanks to the wonders of machine learning, we can analyse cultural shifts on an unprecedented scale. In an important recent study, Adukia et al. (2022) used images in children’s books to trace racial stereotypes. In our study, we examine more than 14 million images from 111,000 high school yearbooks to track style choices over time and space.

We use three main concepts: individualism (how many students within each high school dare to have a different style from their peers), persistence (similarity between present styles and those of 20 years prior), and style novelty (the emergence of previously unseen style choices). Consider Figure 1, showing portraits of graduating seniors from Attica High School in New York in 1966. We can see that they wear very similar clothes – dark suit, tie, collared shirt, no facial hair. We calculate a high measure of similarity based on their style choices of 0.9. The same style of calculation underlies our persistence analysis. We compare cohorts with graduates from the same school 20 years earlier (Figure 2). In panel A, we have low persistence – style choices changed dramatically. In panel B, differences are much smaller, except for some more exuberant bow ties and longer hair. Accordingly, we calculate a high persistence score.

Figure 1 Individualism calculation

Notes: This figure illustrates the calculation of the individualism score. For individual i, it is calculated as (1-mean cosine similarity) when compared with all the images of other seniors with the same gender in the same high school cohort. The score for the individual on the left is 0.098, indicating a low level of individualism, since most style choices (suit, hair, tie) are similar.

These indicators allow us to paint a fascinating picture of cultural evolution in post-war America. Figure 3 gives an overview. The main message is that style characteristics of men and women converged from the mid-60s onwards, as the women’s rights movement erupted and old role models were laid to rest. Both individualism and persistence levels converged by the 1990s.

Men started out in the 1950s and early 1960s with low individualism. They mostly looked like their parents, 20 years earlier. But as Bob Dylan prophesied, the times they were a-changin'. This equilibrium spectacularly collapsed in the late 1960s, with individualism surging. In the following decades, individualism continued to fluctuate around a rising trend.

In contrast, women started off with a lot of within-class variation (‘individualism’), and then saw a decline from the 1960s onwards. At the same time, persistence began to rise from the late 1980s, approaching male levels. Both genders experienced a marked increase in style innovation. Male style novelty exploded in the late 1960s, and both genders reached unprecedented levels by 2010.

Figure 2 Persistence

a) Low persistence example

b) High persistence example

Notes: The figure illustrates the calculation of persistence scores. We calculate the similarity of everyone in a cohort, comparing each of them with the style of graduates 20 years previous (of the same gender). We then average this score for the cohort. Panel (a) is an example of low persistence (0.056). Panel (b) is an example of high persistence (0.83).

We find high and uniform levels of individualism and persistence during the 1950s and across schools. By the 1980s, however, a stark divide began to emerge. Schools became polarised, with some clinging to conformity while others embraced individuality with gusto. Perhaps unsurprisingly, much of the old South remained a bastion of style conformity.

Figure 3 Individualism, persistence, and style novelty over time

a) Individualism

b) Persistence

c) Style novelty

Notes: This figure plots yearly average cosine (for persistence) and 1-cosine (for individualism) scores for individualism (Panel A) and persistence (Panel B); Panel C plots the share of style innovators. Averages come from our image level dataset (14.5 million observations), split by gender.

Figure 4 Individualism over time

Does any of this matter beyond the realm of fashion and hairstyles? Should economists care about necklines and ties in high school yearbooks? As it turns out, there are potentially some significant economic implications. We examine whether style novelty goes hand in hand with technological innovation. To fix ideas, consider the case of one 1972 Cupertino high school graduate – Steve Jobs. Jobs appears with bow tie and tuxedo, sporting long hair and no beard or moustache. At this point in time, fewer than 0.3% of US male graduates had ever worn this style, qualifying him for the ‘style innovator’ category. Jobs also went on to apply for 1,114 patents, of which 960 were granted.

To see if the case of Jobs generalises at the level of the high school, we carefully match style innovation in a commuting zone with patenting rates of those born in that commuting zone, 18 years prior (using data from Bell et al. 2019). Tracking their successful innovation later in life, we find that areas with more style innovation also see greater patenting. Figure 5 shows the results – in every year after graduation, students from high schools in areas with style innovators are markedly more likely to apply for (and receive) patents. While handing out earrings to boys and cutting Mohawks will not necessarily raise technological creativity, schools that permit one of these style innovations may well also produce graduates that excel at the other. Given that innovation is a key driver of economic growth, these findings suggest that growing up in an environment with a little rebellion in one's youth might pay important dividends down the line.

Figure 5 Patenting in commuting zones with and without style innovators, by year since graduation

So, the next time you flip through an old yearbook and chuckle at the outdated styles, remember: you are not just looking at a sequence of fashion oddities and funny expressions, but also at an important dimension of cultural evolution – and one that might have a serious impact on the pace of technological change.

References

Adukia, A, A Eble, E Harrison, H B Runesha and T Szasz (2023), “What We Teach About Race and Gender: Representation in Images and Text of Children’s Books”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 138(4): 2225–2285.

Atkin, D (2016), “The Caloric Costs of Culture: Evidence from Indian Migrants”, American Economic Review 106 (4): 1144–1181.

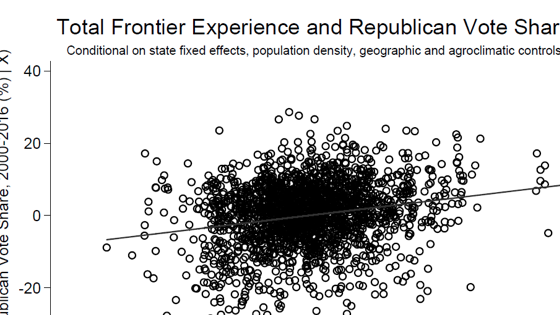

Bazzi, S, M Fiszbein and M Gebresilasse (2020), “Frontier Culture: The Roots and Persistence of “Rugged Individualism” in the United States”, Econometrica 88(6): 2329–2368.

Bell, A, R Chetty, X Jaravel, N Petkova and J Van Reenen (2019), “Who Becomes an Inventor in America? The Importance of Exposure to Innovation”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 134(2): 647–713.

Galton, F J (1878), “Composite Portraits”, Nature 18: 97–100.

Michalopoulos, S and M M Xue (2021), “Folklore”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 136(4): 1993–2046.

Voth, H-J and D Yanagizawa-Drott (2024), “Image(s)”, Working Paper.