The Nobel Prize for economics this year went to William Nordhaus, the ‘father’ of climate change economics, and Paul Romer, for his work on modelling technological change. At a press conference after the announcement of the award, Romer said: “It’s entirely possible for humans to produce less carbon. There will be some trade-offs, but once we begin to produce [fewer] carbon emissions we’ll be surprised that it wasn’t as hard as it was anticipated.” Is there a basis for Romer’s optimism?

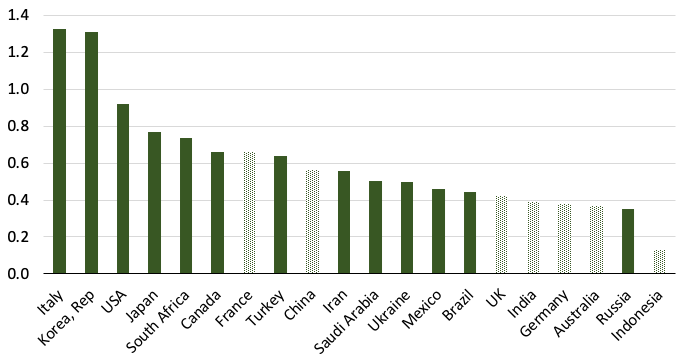

At first blush, the answer would seem to be ‘no’. Figure 1 shows the percentage change in emissions in response to a 1%-change in real GDP, for the 20 largest emitting countries in the world. We use a broad measure of emissions that includes, in addition to carbon emissions, methane, nitrous oxide, and fluorinated gases. These various sources are aggregated by the World Resources Institute, with weights based on their global warming potential as estimated by climate scientists. Real GDP data is from the IMF’s World Economic Outlook database. The elasticities are computed from annual data from 1946 to the present.

Figure 1 Response of emissions to income

Notes: The bars represent elasticities—the change in emissions in response to a 1% change in real GDP. Shaded bars represent estimates that are statistically not significantly different from zero.

As shown, these elasticities are all positive, ranging from 0.13 for Indonesia to 1.3 for Italy. Of the ten countries with the highest elasticities, five are advanced economies. Overall, Figure 1 does not support optimism about the extent of decoupling of emissions and economic activityand explains why year-to-year fluctuations in emissions provoke disputes. Drops in emissions often provoke claims from climate sceptics that worries over global warming are exaggerated, while increases in emissions lead to concerns among environmental groups and climate experts that not enough is being done to address the issue, even in countries such as Germany which areat the forefront in the use of renewable sources of energy (e.g. Wettengel 2016).

Trend versus cycle

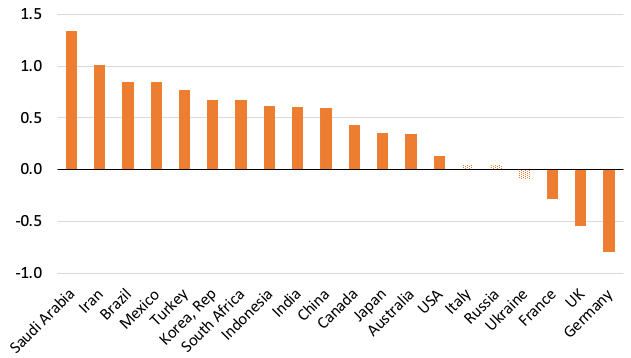

In recent work (Cohen et al. 2017) presented at a workshop in Paris, we suggest that Figure 1 provides a false impression. We present new evidence on the extent of decoupling between emissions and economic activity using the trend/cycle decompositions that are commonly used in econometric work in macroeconomics and allied fields. When we distinguish between trends and cycles, we find that the picture changes quite significantly. This is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Response of trend emissions to trend income

Notes: The bars represent elasticities—the change in trend emissions in response to a 1% change in trend real GDP. Shaded bars represent estimates that are statistically not significantly different from zero.

Now the countries with the ten highest elasticities are all emerging markets. For six of the ten advanced economies, the elasticities are either essentially zero or negative, suggesting that the trend component of emissions has decoupled from the trend component in output. The trend components of emissions and real GDP thus show clear evidence of decoupling in many richer nations, particularly in Europe, but not yet in emerging markets.

All these estimates are based on using the Hodrick-Prescott filter to distinguish trends from cycles. But our estimates are not sensitive to the choice of filter. We get very similar results using the filter recently proposed by Hamilton (2017) or with other filters commonly used in applied econometric work.

Pollution havens?

One possibility for this could be that the advanced economies have decoupled by taking advantage of globalisation. International trade “gives a mechanism for consumers to shift environmental pollution to distant lands” (Peters and Hertwich 2008). It is possible that although developed economies “may have experienced a change in their production structure, their consumption structure remains unchanged”; hence, the decoupling may arise simply because “dirty industries in developed countries tend to migrate” to developing economies (Jaunky 2011).

To account for the effects of globalisation, we make a distinction between production-based and consumption-based emissions, where the latter add in the emissions embodied in the net exports of countries (see Lenzen et al. 2013 for a discussion on how consumption-based emissions are measured). This does make some difference to our resultsand in the expected direction. The evidence for decoupling for the richer nations gets weaker, including for many European countries (France, Germany, Italy, and the UK). For instance, Germany’s trend elasticity based on consumption-based emissions is -0.4, compared to -0.8 for production-based emissions.

Since the globe as a whole cannot export pollution, progress on decoupling requires changes in technology and policies such that production becomes cleaner everywhere over time. Is there evidence that this is happening?

Progress over time and space

To document progress on decoupling over time, we use a longer time series, which is only for CO2 emissions, from the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC), and output data from the Maddison Project. For 16 of our 20 countries, we have data from 1946 onwards. We find that the trend elasticities have indeed declined over the second sub-period (post-1983) compared to the first (1946 to 1982). The average elasticity has declined to 0.7 from 1.1. For 13 countries, we have even longer time series, some extending as far back as 1850. In each case, we find that the trend elasticity computed over the post-1990 period is much smaller than the elasticity over the full sample period; in the case of Germany, for instance, the two estimates are -0.6 and 0.9, respectively.

China is the world’s largest greenhouse gas emitter (Mi et al. 2015). It contributes 23% of world emissions, which is larger than its 19% share of the world’s population and 15% share of the world’s GDP. Progress on global climate change goals will be difficult to achieve unless the paceof emissions slows down significantly in China.

Our analysis points to some positive signs. The trend elasticity of emissions to income for China was three times as large over the 1950–1982 period than in the period since then. This suggests that while China’s opening up of its economy to reforms in the 1980s—and its subsequent strong economic growth—has contributed to growth in emissions, the likely scenario in the absence of reforms would have been even higher emissions growth. We supplement the aggregate analysis with emissions and GDP data for 29 provinces in China. Our evidence indicates that trend elasticities initially increase with provincial per capita real GDP, but then decline. These results thus hold out the hope that the relationship between emissions and GDP growth will weaken as China gets richer. At a time when many subnational entities are taking the lead in tackling climate change (such as by some US states and cities, following the federal decision to pull out of the Paris Agreement), these results are particularly encouraging.

An urgent issue

While there is progress on decoupling, it may not be fast enough. On 8 October 2018, coincidentally around the same time that the Nobel announcement was made, the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change warned that the world has only a dozen years to keep the increase in global temperatures at a maximum of 1.5℃, beyond which even half a degree will significantly worsen the risks of drought, floods, and extreme heat. The panel urged policies that will bring about the needed changes in carbon use, which it said were technologically feasible. Thus, it may take the increases in carbon taxes that Nordhaus (2008) has long advocated to bear out Romer’s optimism that we will confront the challenge of climate change.

Authors' note: The views expressed in this column should not be attributed to the IMF or the National Academies.

References

Cohen, G, J Jalles, P Loungani and R Marto(2017), “Emissions and growth: Trends and cycles in a globalized world”, IMF Working Paper 17/191. (See also: OCP Policy Center 2018 Workshop on Coping with Climate Change materials)

Hamilton, J (2017), “Why you should never use the Hodrick-Prescott filter”, NBER Working Paper 23429.

Jaunky, V (2011), “The CO2emissions-income nexus: Evidence from rich countries”, Energy Policy 39(3): 1228–1240.

Lenzen, M, D Moran, K Kanemoto and A Geschke (2013), “Building Eora: A global multi-regional input-output database at high country and sector resolution”, Economic Systems Research 25(1): 20–49.

Mi, ZF, SY Pan, H Yu and YM Wei (2015), “Potential impacts of industrial structure on energy consumption and CO2 emission: A case study of Beijing”, Journal of Cleaner Production 103: 455–462.

Nordhaus, W (2008), A question of balance: Weighing the options on global warming policies, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Peters, G, and E Hertwich (2008), “CO2embodied in international trade with implications for global climate policy”, Environmental Science and Technology 42(5): 1401–1407.

Wettengel, J (2016), “German carbon emissions rise in 2016 despite coal use drop”, Clean Energy Wire, 20 December.