Over the past decade, fintechs and Big Techs began to offer financial services initially outside the banking system, with several recently gaining approval to operate banks in Asia, Europe, and in the US. These developments have been supported by secular trends – such as the availability of mobile devices – and turbocharged by the Covid-19 pandemic.

Tech firms fall within the spectrum of ‘non-financial companies’ (NFCs) that have sought a banking license. In some jurisdictions, banking authorities have traditionally curtailed certain NFCs – such as big commercial and industrial firms – to own a bank. They have discouraged such affiliations due to prudential concerns surrounding potential conflicts of interest, competition issues, contagion and systemic risks, and the capacity to conduct group wide supervision (Acharya and Rajan 2020, Blair 2004, Wilmarth 2020).

Why have some prudential authorities allowed these new classes of NFCs –– including Big Techs and fintechs –– to own banks? Are the supervisory concerns regarding the affiliation between banks and big corporates relevant in the context of tech firms’ pursuit of a banking license? What prudential safeguards can be introduced to minimize the perceived risks without undermining the potential benefits their entry may bring to society? In a recent paper (Zamil and Lawson 2022), we delve into these questions by framing the discussion as part of a longstanding debate on whether to allow the mixing of banking and commerce in a modern, digital context.

Benefits and risks of tech-owned banks

Tech firms generally are better positioned to deliver on some authorities’ policy objectives of promoting inclusion and fostering competition compared to traditional NFCs. The proliferation of mobile devices, together with their deployment of superior technology and user-friendly apps, can enable tech firms to reach a broader range of underserved consumers and to perform various aspects of the banking business more efficiently and at a cheaper cost. Tech firms may also have more access to and greater ability in evaluating consumer data (Feyen et al. 2021). This may help with assessing borrower creditworthiness, facilitating better pricing and enhancing product offerings, which may improve consumer outcomes.

Nevertheless, some tech firms may pose similar – if not greater - risks as traditional NFCs across five risk dimensions.1

- Conflicts of interest: A bank may be compelled to engage in transactions at more favourable terms with its corporate parent or to affiliated non-financial entities controlled by the same parent, which can undermine its strength.

- Competition: Large NFCs may use their existing customer base, financial resources, and market power to subsidise their banks’ activities and gain market share, which could erode competition.

- Contagion and systemic risk: Affiliations between NFCs and banks may be such that financial distress at one may cause distress at the other, risking spillover effects from the financial sector to the real economy or vice versa.

- Consolidated supervision: Banks owned by NFCs may be part of large corporate groups with multiple subsidiaries and affiliates, which can pose a challenge for supervisors to perform group-wide supervision.

- Parent company support: During authorisation, supervisors consider the parent’s ability to provide financial support to the bank. Similar to commercial NFCs, the financial capacity of tech firms varies with several continuing to record net losses, as they expand their digital footprint.

A framework to assess tech firms’ risk profile

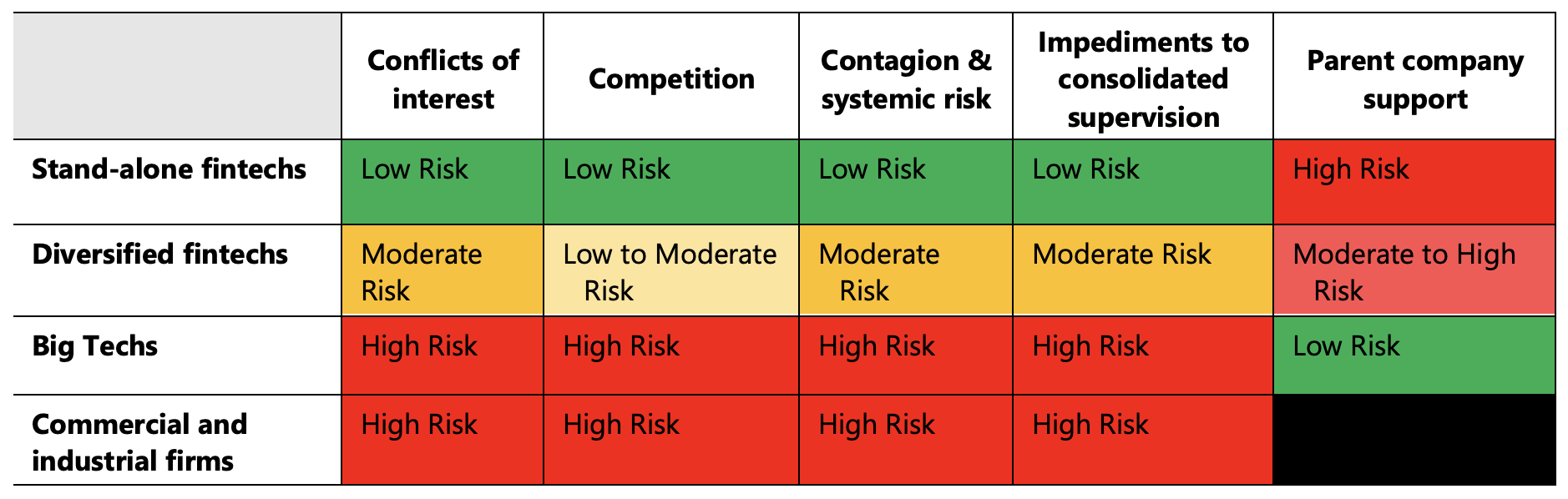

To determine their risk characteristics and to help inform policy options, we disaggregate tech firms that engage in financial activities into three groups and compare them against commercial and industrial NFCs across five risk factors (Table 1):

- ‘Stand-alone fintechs’ are firms whose financial activities are conducted solely or primarily through their banking entity.

- ‘Diversified fintechs’ are firms who engage in a broader range of financial services through various channels, including the parent entity level, their banking subsidiary and other non-bank subsidiaries, joint ventures and affiliated companies.

- 'Big Techs’ are firms with core non-financial businesses in social media, internet search, software, online retail and telecoms, who also offer financial services as a secondary business line (Financial Stability Board 2020).

Table 1 NFCs and bank ownership – potential risks

Source: FSI analysis

Among tech firms, Big Techs pose the highest risks, followed by large, diversified fintechs (Carstens et. al 2021, Crisanto et al. 2021a).3 This assessment is based on the relative complexity of their organisational structures, the scale of their financial and non-financial lines of businesses, the size of their captive user networks, abundance of data and financial resources, which, collectively can have complex interactions with their in-house bank. These attributes can accentuate potential supervisory concerns across the first four risk dimensions. However, Big Techs have greater market access – compared to other tech firms – providing them with more flexibility to provide financial support to their banking entity.

The regulatory landscape for tech-owned banks

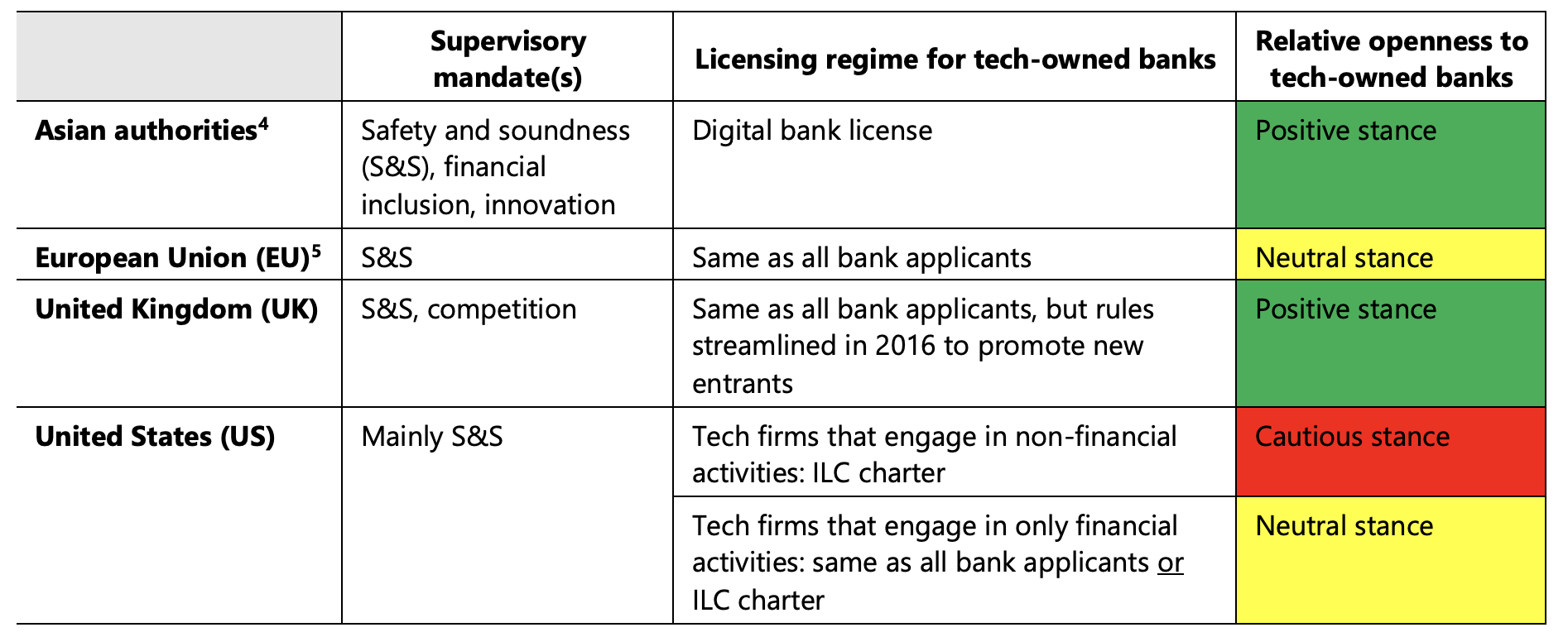

Banking supervisors are guided by a set of core principles issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, which provide standards for the regulation and supervision of banks (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2012). One of these principles outlines licensing requirements, which oblige supervisors to prescribe minimum capital levels and assess, among other issues, the applicant’s ownership structure, governance, major shareholders, and the parent’s ability to provide financial support. Despite a similar starting point, authorities apply varying licensing regimes to tech-owned bank applicants (Table 2).

Table 2 Supervisory mandates, licensing regimes and regulatory posture

Source: FSI analysis

Authorities with mandates that encompass financial inclusion, technological innovation or competition appear more inclined to license tech-owned banks. Among these jurisdictions, some have developed digital bank licenses (various Asian jurisdictions), while others streamlined their general bank licensing process to promote competition (UK). In jurisdictions where mandates are more narrowly focused on ‘safety and soundness’, they tend to be policy neutral (EU) or more cautious (US) in licensing tech-owned banks. EU supervisors use their existing bank licensing process to assess tech-owned applicants. In the US, fintechs that engage in only financial activities may apply for a traditional bank charter, but tech firms that engage in any non-financial activity (such as Big Techs) must obtain an ‘industrial loan company’ (ILC) charter.6

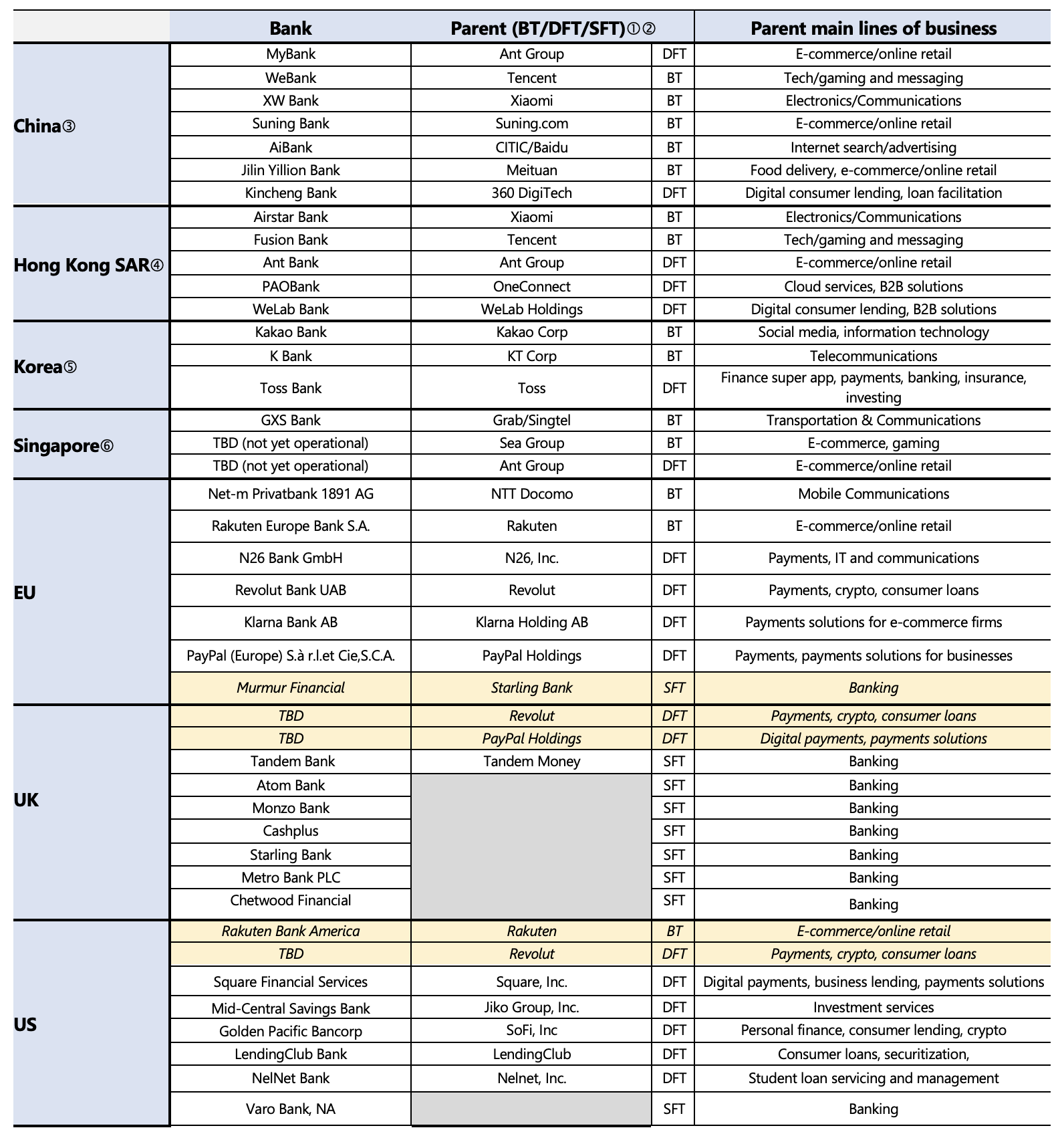

Table 3 provides a snapshot of tech firms with approved or pending bank licenses in selected jurisdictions.

Table 3 Tech firms with approved or pending banking licenses – ownership and main business lines7

Source: Company regulatory filings; FSI analysis.

While the US, arguably, imposes the most onerous licensing requirements, Asian authorities that are relatively ‘tech-friendly’, aim to tailor their licensing requirements to the structure and business models of these new entrants.8 Among various quantitative and qualitative requirements, some provisions are noteworthy:

- Measures designed to reduce systemic risk: All jurisdictions require tech-owned banks to develop an exit plan in case of failure, while some impose higher capital requirements on them.11 The US prohibits an ILC chartered bank from entering into any contract for services material to its operation with the tech parent or their affiliated companies.10

- Consolidated supervision: China and Hong Kong require tech-owned parents meeting certain criteria to consolidate all financial entities within the group into a financial holding company to facilitate group-wide supervision.

- Prohibition on overlapping boards and senior executives: The US prohibits parent companies from having a majority board representation on the ILC bank, while restricting the hiring of senior executives at the ILC bank if the individual has been associated with the tech parent in past three years. These measures, together with comprehensive rules governing transactions between a bank and its related parties, may help to minimise conflicts of interest.

- Competition: China prohibits Big Techs with bank subsidiaries from abusing their market power or technological superiority. Korean regulations limit any company in violation of anti-monopoly rules over the past five years from owning more than 10% of a bank. No other jurisdictions have explicit competition-related provisions in their licensing frameworks, but efforts are underway to identify ‘dominant’ firms and impose requirements to address competition issues (Crisanto et al. 2021b).

- Parent company support: While all jurisdictions assess tech parents’ ability to financially support its bank subsidiary, only a few require tangible evidence of parent company support. China requires the tech parent to be profitable for a period of at least two consecutive years, while the US requires the tech parent and/or principal shareholders to pledge assets or secure a line of credit to demonstrate support to the subsidiary bank.

Conclusions

Tech firms’ entry into the banking system may advance various public policy goals, but it also introduces new risks and amplifies older ones. New risks – particularly for Big Techs and diversified fintechs – stem from their scalable business models that are premised on extracting data from their large and captive user base that can be leveraged as they enter banking. These features may aggravate traditional concerns when banks affiliate with large NFCs. Moreover, several tech firms remain unprofitable, raising questions on their ability to support their in-house bank.

While authorities impose various qualitative and quantitative licensing requirements, they are not always tailored to tech firms’ risk characteristics. In most jurisdictions, authorities aim to follow the principle of ‘same activity, same risk, same regulation’. However, the same banking activity performed by certain tech firms may not necessarily lead to the same risks (Restoy 2021). These developments call for differentiated licensing rules among tech firms.

The American rapper and music producer will.i.am once said, “Magazines and websites are the gatekeepers of what people think hip-hop is, but they actually end up limiting what hip-hop can be”. The entry of tech firms in banking provides supervisory authorities with a unique opportunity to steer the global banking landscape. Their challenge is to strike a balance between setting bank licensing requirements that are commensurate with tech firms’ inherent risk characteristics and prescribing overly onerous rules that shield incumbents from healthy competition which could hinder technological innovations in the provision of financial services.

Authors note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of their employers, including the Bank for International Settlements or the Basel-based standard setters.

References

Acharya, V and R Rajan (2020), “Do we really need Indian corporations in banking?”, November.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2012), “Core principles for effective banking supervision”, September.

Blair, C (2004), “The mixing of banking and commerce: Current policy issues”, FDIC Banking Review 16(3 and 4): 97–120.

Carstens, A, S Claessens, F Restoy, and H S Shin (2021), ”Regulating Big Techs in finance”, BIS Bulletin 45, August.

Crisanto, J C, J Ehrentraud, and M Fabian (2021a), “Big Techs in finance: Regulatory approaches and policy options”, FSI Briefs no 12, March.

Crisanto, J C, J Ehrentraud, F Restoy, and A Lawson (2021b), “Big tech regulation: What is going on?”, FSI Insights on Policy Implementation 36, September.

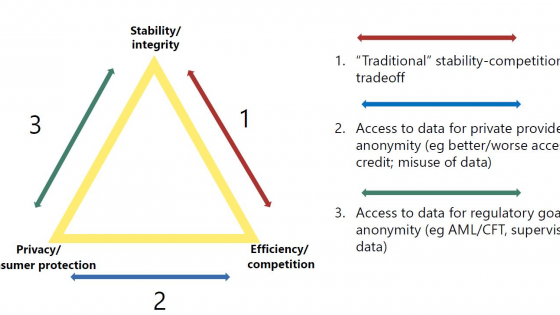

Feyen, E, J Frost, L Gambacorta, H Natarajan, and M Saal (2021), “A policy triangle for Big Techs in finance”, VoxEU.org, 23 October.

Financial Stability Board (2020), “BigTech firms in finance in emerging market and developing economies – market developments and potential financial stability implications”, 12 October.

Restoy, F (2021): “Fintech regulation: How to achieve a level playing field”, FSI Occasional Papers 17, February.

Wilmarth, A (2020), “Re: FDIC Docket RIN 3064-AF31 – Notice of proposed rulemaking: “Parent companies of industrial banks and industrial loan companies”, 85 Fed. Reg. 17771, 10 April.

Zamil R and A Lawson (2022), “Gatekeeping the gatekeepers: when bigtechs and fintechs own banks- benefits, risks and policy options”, FSI Insights on policy implementation No 39, January.

Endnotes

1 For additional discussion on the growth of fintech and the risks they pose to financial stability, refer to the IMF’s April 2022 Global Financial Stability Report, Chapter 3.

2 The classification of “low”, “moderate” and “high” risk are based on the authors’ judgment of the inherent risks associated with tech firms across the specified risk dimensions. Within a group of tech firms, there may be variations in risk dispersion that cannot be captured through this generalised methodology.

3 Stand-alone fintechs pose the least prudential concerns among tech firms across the first four risk dimensions due to their small size and lack of a complex organizational structure. Nevertheless, they still pose various challenges which need to be considered during the licensing process, including the viability of their business models, the adequacy of risk management, and the ability of sponsors to support the bank.

4 Asian authorities covered in our paper include China, Hong Kong, Korea, and Singapore

5 The mandate of the single supervisory mechanism of the European Central Bank is used as a proxy for the supervisory mandate of the EU.

6 The ILC charter was initially developed for commercial-industrial NFC bank owners, but provides scope for authorities to tailor requirements for tech-owned bank parents.

7 This table is not an all-inclusive list and provides a selected overview of approved or pending banking licenses.

8 As an example, while China has been at the forefront in encouraging tech firms to obtain digital bank licenses, they have also introduced a range of policy measures (ex-post) to address the underlying risks.

9 In the US, Square Financial Services and Nelnet Bank – two recent ILC charter approvals – are required to maintain minimum leverage capital ratios of 20% and 12%, respectively, much higher than the 8% leverage ratio for other newly licensed banks. Singapore requires digital full service banks to maintain the same risk-based capital ratios as a domestic systemically important bank after an initial phase-in period.

10 This provision can help authorities to extricate the activities of the bank from the tech parent, if needed.