This column is a lead commentary in the VoxEU Debate "The Future of Digital Money"

From the ancient Indian rupya, to cacao beans in the Aztec empire, to the first paper money in China, the countries that are today referred to as emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs) have seen innovation in money and payments for centuries. In recent decades, physical cash and claims on commercial banks (i.e. deposits) have become the main vehicles for retail payments around the world (Bech et al. 2018). Compared to physical cash, commercial bank money provides more safety, enables remote transactions, and allows banks to extend other useful financial services.

Yet for retail users, especially in EMDEs, commercial bank money poses at least three key challenges. First, it requires a bank account – access to which is far from universal. The poor often lack the proper documentation to comply with banks’ customer due diligence (CDD) requirements. In some cases, they live too far from a bank branch, or find the maintenance costs or minimum balances too onerous. As a result, the poor rely heavily on cash, which perpetuates informality.

Second, despite improvements in recent years, financial institutions in many EMDEs face limited competition. This concentrated market power results in limited innovation and poorer, more expensive financial services. Together with past experiences of financial crises, this contributes to a lack of trust in the formal banking system.

Third, many households in EMDEs depend on low-value cross-border remittances from family members working abroad. Remittances exceed official aid by a factor of three and are on track to overtake foreign direct investment inflows (World Bank 2019). Specialised money transfer operators have emerged to provide near instantaneous transfers, and to reduce the costs for sending money over time. Yet it still costs about $14 on average to send $200 back home (World Bank 2019). This is largely because of the role of cash on both sides of the remittance (‘cash-in, cash-out’). Micro, small and medium-sized enterprises (MSMEs) and individuals participating in cross-border trade in EMDEs have an even bigger problem. They are dependent on banks and specialised providers that in turn often depend on the slow and opaque correspondent banking system.

Enter stablecoins

Various crypto-assets claim to address deficiencies in the existing financial system. Many are vying to become a new form of digital money that can be securely sent and received over the internet, by anybody with a phone or internet connection, and with the convenience and cost-effectiveness of an email. Some initiatives target cross-border payments, particularly remittances, in EMDEs. By cutting out financial intermediaries, such proposals aim to empower users and make domestic and cross-border payments more efficient. This may be particularly relevant for country corridors hit by a decline in correspondent banking relationships (CPMI 2016, IMF 2017, FSB 2019a), and for those countries with growing participation in the digital economy but no corresponding growth in access to e-commerce-enabled payment mechanisms.

Crypto-assets have suffered from various impediments, including high price volatility and scalability challenges, which prevent them from being adopted as a mainstream means of payment or store of value, much less a unit of account (see BIS, 2018). In response, a diverse family of so-called stablecoins has entered the fray. Most stablecoins attempt to maintain a stable value relative to a fiat currency (like e-money or a currency board) or a basket of fiat currencies. To maintain a stable value, most initiatives adopt a collateral approach using bank deposits, government securities or crypto-assets (Moin et al. 2019). This would be no small feat as the eventful history of broken currency boards and pegs has shown. Further, stablecoin systems that can tap into the massive user bases of platform companies may employ network effects to drive rapid adoption on a global scale.

However, as pointed out by a recent G7 report and ongoing FSB work, stablecoins pose a wide range of risks related to, among others, legal certainty, financial integrity, sound governance, the smooth functioning of payments, consumer protection, data privacy, tax compliance, and potentially monetary policy and financial stability (G7 Working Group on Stablecoins, 2019; FSB, 2019b). Moreover, stablecoins face many of the same obstacles that other players have faced with transaction accounts. Further, they need to contend with new challenges of their own depending on the scale of adoption and their use as a means of payment or a store of value.

Particular challenges for EMDEs

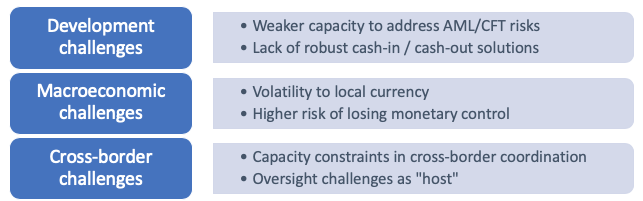

Several issues related to stablecoins are exacerbated in EMDEs. Authorities are confronted with six main development,1 macroeconomic, and cross-border challenges (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Particular challenges of stablecoins for EMDEs

First, stablecoin systems could pose severe anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) risks (FATF 2019a). Stablecoin systems need to comply with the standards of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) to mitigate their use for illicit financial activities. These were recently amended to cover virtual assets service providers (VASPs) such as crypto-exchanges, who will now also need to conduct CDD (FATF 2019b). In their current conception, most stablecoins projects do not seek to link ‘accounts’ to real-world identities. This raises regulatory arbitrage concerns if significant volumes of transactions occur in a peer-to-peer fashion rather than using VASPs or other financial intermediaries. While this affects authorities around the world, EMDEs may have more difficulty keeping pace and adjusting their surveillance, regulatory and supervisory frameworks, given resource constraints.

Second, like branchless banking and e-money networks, stablecoin systems would need to offer robust and secure ‘cash-in/cash-out’ functions between stablecoins and fiat currency through physical agent networks – for mobile money this accounts for about 70% of transactions. This is challenging if distribution networks are not equipped to handle crypto-asset or stablecoin transactions, lack geographical coverage or are prone to cyber-attacks. So far, it is unclear whether stablecoin systems would work on simpler ‘feature phones’ and in locations with poor connectivity, or whether they could better address the challenges posed by a lack of ID for onboarding the unbanked, particularly in remote locations.

Third, fundamentally, stablecoins will fluctuate against local currencies in EMDEs. This inhibits their adoption for daily payments since prices will remain denominated in local currencies in all but the most extreme cases. If used for debt contracts, this is a new form of foreign exchange (FX) lending. FX lending has been at the heart of many financial crises in EMDEs.

Fourth, depending on the prevalence of their use domestically, stablecoins import the monetary policies of the fiat currencies in the basket that may not be optimal for most EMDEs and could thus impinge on their monetary policies. ‘Stablecoin-isation’ could mean less effective monetary transmission and, in the extreme, countries that face shocks – political, economic or financial – could face deposit outflows from banks and capital flight. This would amplify instability and render policy measures less effective. Countries with large cross-border inflows in stablecoins may face difficulties to maintain international reserves in hard fiat currencies. This has implications for the functioning of FX and interbank markets, which are shallower in EMDEs. Liquidity and redemption shocks may thus create disruptive spillovers.

Fifth, stablecoin systems may combine elements of multiple regulatory frameworks, for example for payment systems, bank deposits, e-money, commodities, FX, and securities. In some jurisdictions, there may be gaps as no specific framework would apply. This may create an unlevel playing field if countries adopt different regulatory approaches. EMDEs may have more difficulty to allocate proper resources to adjust their policy frameworks, adopt proportionate supervision, and engage in coordination across borders.

Sixth, EMDEs will likely act as a ‘host’ to most entities in a stablecoin system, which may be headquartered elsewhere. As such, authorities may lack control over stablecoin payments that involve residents. When domestically adopted at scale, this could inhibit monitoring of risks and effective oversight of payments to prevent illicit use and foster financial stability, as mandated by international standards. Moreover, it raises questions on consumer protection and redress mechanisms.

Many of these challenges can be addressed, or at least mitigated, by adequate policies. These could include additional resources on AML/CFT supervision, regulations to limit currency mismatches, and further international coordination. Yet, such policies take time and resources to be enacted, and the potential opportunities from stablecoins have to be weighed against the substantial risks.

Technological advances are already enhancing inclusion and efficiency

Fortunately, stablecoins are not the only game in town. In recent decades, technological advances have given EMDEs an opportunity to ‘leapfrog’ into the digital economy (IMF and World Bank Group 2018). Fintech facilitates the digitisation of money, making accounts and payments services more accessible, safer, cheaper, more convenient, and closer to real time. As a result, in sub-Saharan Africa, the share of adults with an e-money account nearly doubled from 2014 to 2017, to a level of 21%. Globally, 52% of adults used digital payments in 2017, up from 42% in 2014 (Demirgüç-Kunt et al. 2018). Across all levels of economic development, the share of unbanked adults and the costs of remittances are falling. Several factors have facilitated these developments.

First, policymakers are facilitating fintech innovation and adoption by updating policy frameworks and promoting digital literacy. Many countries are working on digital ID systems, which provide the opportunity to bring the over one billion undocumented people into the financial sector and promote transaction security. The experience with Aadhaar in India is particularly instructive (D’Silva et al. 2019).

Second, authorities are upgrading payment infrastructures with ‘fast payments’, allowing banks and eligible non-banks to offer 24/7, near real-time payments (Bech et al. 2017). Moreover, ‘open banking’ initiatives allow for third party-initiated payment services,2 often de-coupling transaction accounts from banks and empowering customers. This can help boost competition.

Third, there is a global rise of non-bank e-money issuers such as e-commerce platforms or telecom operators with large user bases that benefit from network effects. E-money is a bridge to commercial bank money, as in most countries it needs to be fully covered by commercial bank money. E-money can be conveniently stored on and exchanged from a phone or online and funds can be transferred through digital channels as well as physical agent locations. This is better suited for many consumers in EMDEs, particularly those who live in remote areas.

Fourth, feeling the pressure to innovate, incumbent banks and payment providers are embracing fintech to improve their services so consumers can conduct payments more conveniently, faster and 24/7. For example, many incumbent banks are joining hands, in some cases also with non-banks, to develop fast payment networks and offer access to their deposit-based products via mobile apps (Petralia et al. 2019).

Finally, new fintechs have extended the money transfer operator model for cross-border transfers by connecting to local payment infrastructures and banks or e-money providers on both sides of a transaction. Further, the global financial messaging network SWIFT has launched the Global Payments Initiative (SWIFT gpi) to bring transparency, speed and reliability to correspondent banking transactions.

Conclusion

Stablecoin arrangements aspire to improve financial inclusion and cross-border remittances – but they are neither necessary nor sufficient to meet these policy goals. It is unclear whether they would offer lasting competitive advantage to rapidly evolving digitalization of money and payments services that are built on top of or aim to improve existing financial plumbing. Innovations such as digital ID, e-money, mobile banking, open banking, and Faster Payment system may be adequate in a domestic setting. The development of SWIFT gpi and the integration of Faster Payment systems could help improve cross-border payments, although more work is clearly needed.

Meanwhile, stablecoins face various challenges and pose new risks, particularly in EMDEs. Thus, authorities may consider limiting or even prohibiting the use of stablecoins as a means of payment, and bar regulated entities such as banks and agent networks from holding stablecoins or offering stablecoin services.

Some countries have reacted by accelerating their investigations into a central bank digital currency (CBDC) for consumers. However, a new digital equivalent to cash also raises various challenges (CPMI-MC 2018) and it is not yet clear whether it is necessary or desirable.

Taken together, perhaps the most important contribution of stablecoins thus far is that they have drawn greater – and welcome – attention to the challenges of financial inclusion and more efficient cross-border payments and remittances. This highlights the efforts underway to strengthen monetary and financial stability frameworks; promote an enabling regulatory environment for fintech; upgrade payment infrastructures, particularly across borders; and ensure a global regulatory level playing field through greater collaboration.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily of the World Bank or Bank for International Settlements. The authors thank Raphael Auer, Stijn Claessens, Sebastian Doerr, Matei Dohotaru, Alfonso Garcia Mora, Leonardo Gambacorta, Marc Hollanders, Yira Mascaro, Tara Rice, Hyun Song Shin, and Mahesh Uttamchandani for comments.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2018), Cryptocurrencies: Looking Beyond the Hype, BIS Annual Economic Report, June.

Bech, M, T Shirakami and P Wong (2017), “The quest for speed in payments”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Bech, M, U Faruqui, F Ougaard and C Picillo (2018), “Payments are a-changin' but cash still rules”, BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures (2016), “Correspondent banking,” July.

Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures and Markets Committee (2018), “Central Bank Digital Currencies,” March.

D’Silva, D, Z Filkova, F Packer and S Tiwari (2019), “The design of digital financial infrastructure: lessons from India”, BIS Paper No 106.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A, L Klapper, D Singer, S Ansar, and J R Hess (2018), The Global Findex Database 2017: Measuring Financial Inclusion and the Fintech Revolution, April.

Financial Action Task Force (2019a), “Money Laundering Risks from “Stablecoins” and Other Emerging Assets”, October.

Financial Action Task Force (2019b), “Public Statement on Virtual Assets and Related Providers,” June.

Financial Stability Board (2019a), “FSB Action Plan to Assess and Address the Decline in Correspondent Banking: Progress Report,” May.

Financial Stability Board (2019b), “Regulatory Issues of Stablecoins”, October.

G7 Working Group on Stablecoins (2019), “Investigating the Impact of Global Stablecoins,” October.

International Monetary Fund (2017), “Recent Trends in Correspondent Banking Relationships: Further Considerations,” policy paper, April.

International Monetary Fund and World Bank Group (2018). “The Bali Fintech Agenda.”

Moin, A, E Gün Sirer, and K Sekniqi (2019), “A Classification Framework for Stablecoin Designs,” arXiv:1910.10098v1.

Petralia, K, T Philippon, T Rice and N Véron (2019), Banking Disrupted? Financial Intermediation in an Era of Transformational Technology, Geneva Reports on the World Economy 22, ICMB and CEPR.

World Bank (2019), “Remittance Prices Worldwide,” September.

Endnotes

1 Development challenges refers here to the specific policy challenges around financial sector development, including financial deepening, financial infrastructure, financial inclusion and institutional underpinnings like sound regulation and supervision.

2 Open banking refers to a system in which financial institutions’ data can be shared for users and third-party developers, for example through application programming interfaces.