US-China decoupling is currently underway. The Xi Jinping administration proposed for the first time the concept of “Comprehensive National Security” as the guiding principle for its national security policy on 15 April 2014. To implement this concept, the National Security Law was issued on 1 July 2015. Since then, a series of security-related laws have been introduced, including the Cyber Security Law (2017), the Data Security Law (2021), and the revised Anti-Espionage Law (2023). Moreover, since 1 January 2020, security screening of foreign direct investment (FDI) in China has been strengthened through the Foreign Investment Law, and the Export Control Law, which entered into force on 1 December 2020, comprehensively regulates exports of goods for the purpose of national security.

On the US side, the Export Control Reform Act (ECRA) was enacted on 13 August 2018, to regulate the export of technologies that possess dual-use characteristics. Moreover, export controls on advanced computing and semiconductor manufacturing items have been tightened since 13 October 2022. Stringent regulations have also been introduced governing FDI. The Foreign Investment Risk Review Modernization Act (FIRRMA) was signed into law on 13 August 2018, strengthening and modernizing the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States (CFIUS), which reviews transactions involving inward FDI in the US, and expanding the coverage of transactions to be reviewed by the CFIUS from the national security perspective. As for outward FDI, to prevent unauthorised dissemination of technology in high-tech industries, President Biden signed an executive order to restrict FDI to China in specific areas of technology on 9 August 2023. To implement the executive order, the US Department of Treasury issued a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking on 21 June 2024. Despite rising tensions between the two countries, US Treasury secretary Janet Yellen said in her speech in April 2023 that Washington does not seek to decouple the US economy from China’s: “A full separation of our economies would be disastrous for both countries” (Sevastopulo 2023). Jake Sullivan, Biden’s national security advisor, explained in his speech at the Brookings Institution on 27 April 2023, that the US is trying to protect their technologies “with a small yard and high fence” approach (The White House 2023). Given the current situation, policymakers and academic scholars are greatly concerned about possible economic consequences of US-China technological decoupling.

There have been several recent studies that have quantified the impact of technological decoupling. In a framework of a two-country dynamic general equilibrium model of trade with technology transfer through exports of high-tech industries, Garcia-Macia and Goyal (2020) conduct a simulation of US export or import bans against China. They show that a US export ban against China would result in an increase in US welfare by 0.6 percentage points and a decrease in Chinese welfare by 6.1 percentage points, compared with free trade. Cerdeiro et al. (2021) use a multi-country dynamic general equilibrium model to analyse the effects of decoupling on the global economy. They analyse the effects of an elimination of US-China bilateral trade of high-tech industries with productivity losses and diminished knowledge diffusion in the ten-year scope and find that China's welfare falls as much as 2% and US welfare by 1%. Góes and Bekkers (2022) construct a dynamic general equilibrium model of trade that accounts for the knowledge diffusion among countries and analyse the impact of decoupling between the Western and Eastern blocs. In their model, technology diffuses from foreign countries to the home country through the imports of intermediate goods. They show that, in the case of a full decoupling where trade between the two blocs is completely shut down, the welfare losses in the Western bloc range from 1% to 8% (median: 4%), while losses in the Eastern bloc range from 8% to 11% (median: 10.5%).

These previous studies do not separate international technology flows from trade flows. As a result, they do not evaluate the impact of restricting technology diffusion or that of export controls separately. In order to overcome this limitation, our recent paper (Jinji and Ozawa, 2024) employs a simple dynamic quantitative general equilibrium model of trade that includes FDI as a channel of international technology diffusion. The model was originally developed by Anderson et al. (2019). We extend their model by dividing sectors into final and intermediate goods sectors, with technology capital being employed only in the intermediate goods sector.

Model setting

Our model consists of N countries and two sectors. The final goods, which are non-traded, are produced from labour and composite intermediate goods. The intermediate goods, which are differentiated by place of origin, are produced from physical capital and technology capital. Each country can have access to other countries’ technological knowledge through inward FDI from those countries. Thus, in this model, FDI is a channel of international technology diffusion. A parameter captures the degree of openness of country i’s technology to country j at time t. A country can restrict the access from other countries to its technology by changing this parameter. Moreover, the export of the intermediate goods from country i to country j at time t is subject to the iceberg trade costs. In each country, both physical and technology capital are accumulated over time, which establishes the dynamic nature of the model.

Counterfactual analysis

Key parameters of the model are calibrated using data from 89 countries in 2016. Thus, the baseline equilibrium is calculated based on the situation in 2016.

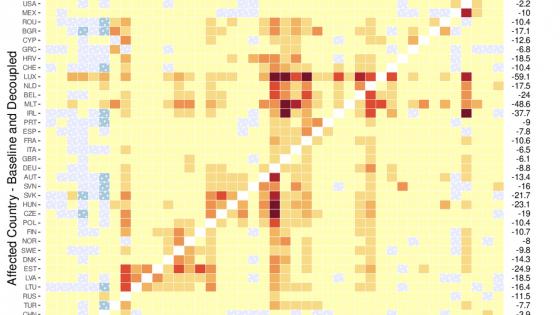

A counterfactual analysis is then conducted based on US-China technological decoupling scenarios. Restrictions of technology diffusion are captured by a decrease in and export controls by an increase in . We simulate the steady-state equilibrium in counterfactual scenarios and calculate changes in variables of main interest (such as, welfare, export, import, and FDI) from the baseline equilibrium. A typical counterfactual scenario is that decreases by 80% and increases by 20% in both directions between the US and China. In other words, we consider a scenario in which decoupling occurs only between the two countries and no other countries are directly targeted. In this limited scenario, we found that the US, China, and the world as a whole experience welfare loss, but the magnitude of the welfare loss is relatively small. That is, welfare in the US and China is lower by 0.41% and welfare of the world as a whole is lower by 0.11% compared to the baseline equilibrium (Figure 1). Our results suggest that the impact of bilateral decoupling is larger on the trade side than on the FDI side. China's export and import decline by 9.88% and 5.90%, respectively, and US exports and imports fall by 6.89% and 3.63%, respectively (blue and orange bars in Figure 2). By contrast, inward FDI declines only by 1.08% in China and by 1.81% in the US (yellow bars in Figure 2).

Figure 1 Welfare changes due to US-China mutual trade & technology restrictions

Figure 2 Changes in trade and FDI in the US and China due to mutual restrictions

Although it is not clearly delineated in the mutual decoupling scenario, the relative impacts of the US restricting technology and trade flows on the Chinese economy can be illustrated using the scenario of the US unilaterally decoupling from China. In particular, we consider an extreme case in which the US completely stops technology diffusion to China as well as export of intermediate goods to China. In such a case, China’s steady state welfare falls to 1.66% below the baseline equilibrium (“Full ban” in Figure 3). Most of the negative impact is attributed to a restriction of technology flows, because a technology ban alone lowers Chinese welfare by 1.65% (“Technology ban” in Figure 3). By contrast, if the US only stops export of intermediate goods to China, China’s welfare declines only by 0.014% (“Trade ban” in Figure 3). It is, however, important to note that in the event of the US unilaterally decoupling from China, US welfare and the welfare of the world as a whole would decrease by 0.14% and 0.31%, respectively (“Full ban” in Figure 3). Therefore, the US and partner countries would additionally suffer from the US unilaterally decoupling from China, and not only China itself.

Figure 3 Welfare changes due to potential, unilateral US bans against China

Concluding remarks

The economic consequences of the currently ongoing US-China technological decoupling are important not only for the US and China but also for other countries. The decoupling involves both export controls and regulations on technology diffusion. This column demonstrated that understanding the mechanism through which decoupling affects each economy requires the separate, individual evaluations of the impacts of these restrictions.

Two policy implications can be drawn from our simulation results. First, the welfare impact on the Chinese economy of the US restrictions on technology diffusion to China could be larger than that of US restrictions on export of targeted sectors to China. Thus, it is important to carefully evaluate the impact of each policy. Second, the negative impact of a US-China technological decoupling on steady-state welfare could be relatively small if the decoupling is restricted to the relationship between the two countries. However, the impact will become much larger as the number of countries involved in decoupling increases.

Editors’ note: The main research on which this column is based (Jinji and Ozawa 2024) first appeared as a Discussion Paper of the Research Institute of Economy, Trade and Industry (RIETI) of Japan.

References

Anderson, J E, M Larch, and Y V Yotov (2019), “Trade and investment in the global economy: a multi-country dynamic analysis”, European Economic Review 120: 103311.

Cerdeiro, D A, J Eugster, R C Mano, D Muir, and S J Peiris (2021), “Sizing up the effects of technological decoupling”, IMF Working Paper. WP/21/69.

Garcia-Macia, D and R Goyal (2020), “Technological and economic decoupling in the cyber era”, IMF Working Paper. WP/20/257.

Góes, C and E Bekkers (2022), “The impact of geopolitical conflicts on trade, growth, and innovation”, WTO Staff Working Paper. ERSD-2022-09.

Jinji, N and S Ozawa (2024), “Impact of technological decoupling between the United States and China on trade and welfare”, RIETI Discussion Paper Series No. 24-E-041.

Sevastopulo, D (2023), “Janet Yellen warns US decoupling from China would be ‘disastrous’”, Financial Times, Online edition on April 23, 2023.

The White House (2023), “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution”, 27 April 2023.