Economics has a longstanding identity crisis when it comes to positive versus normative analysis. The positive camp views the field as properly devoid of moral sentiment. The normative camp thinks maximising social welfare is the discipline’s mission. The ‘positives’ endorse only reforms delivering Pareto gains – winners without losers. The ‘normatives’ choose sides, using economics to do most ‘good’ at least harm.

Nowhere is the conflict between the value-free science of economics and the moral mission of political economy, the discipline’s original name, clearer today than in the economics of climate change. Nordhaus’ seminal, Nobel Prize-winning work identified anthropogenic planetary heating as the world’s most dangerous externality and carbon mitigation as the proper response (Nordhaus 1979, 2017). He also raised a host of issues that now occupy a small army of climate scientists and economists. The list includes the linkage between carbon emissions and atmospheric concentration; the impact of carbon concentration on global mean temperature; the dependence of regional on global temperature; the sources, sizes, measurement, and geographic distribution of damages; the potential for tipping points; global policy coordination; uncertainty; the role of green investment; the Green Paradox; and, last, but really first, the optimal carbon tax.

Yet, for all its value added, Nordhaus’ invocation of a social planner whose intergenerational preferences dictate ‘optimal’ climate policy inextricably conflated questions of economics and morality. The 700-page Stern climate report (Stern 2007), commissioned by the UK government, adopted Nordhaus’ approach. However, Stern summoned forth a social planner who cared far more for posterity, and therefore calculated a far higher ‘optimal’ carbon tax. In questioning the ethics of Nordhaus’ social planner, who had reigned supreme for years, Stern opened the flood gates. In short order, a bevy of economists, including six current or future Nobel laureates,1 were hotly debating ‘the’ social planner’s ethically correct time preference rate – the rate at which to discount, as in make less of, the welfare of the unborn.

Economists cherish scientific objectivity, or at least the appearance of scientific objectivity. Hence, when joined, the social planner approach was quickly re-packaged in positive terms. The trick was to assume intergenerationally altruistic agents, each of whom cared for their offspring but, sadly, no one else’s. The role of carbon policy was to keep these ‘single agents’ from free-riding on one another. Doing so involved maximising the representative single agent’s utility, which, low and behold, devolved to Nordhaus’ selfsame social planner problem. However, the time preference rate could now be viewed as an objective component of household preferences, not a matter of religious creed. Stated differently, any given single-agent model’s weighting of the welfare of the unborn was suddenly rationalised as a matter of professional judgement about an objective quantity, not an ethical declaration.

This ex-post rationale might hold water were we to live in a world of intergenerational altruists. We do not. Most people conduct their economic lives with little or no regard for the economic welfare of their immediate, let alone future descendants. This is plain as day in cohort and household data.2

Greta Thunberg got all this right in her 2019 United Nations address:

“You are failing us. But the young people are starting to understand your betrayal. The eyes of all future generations are upon you. And if you choose to fail us, I say: We will never forgive you.” 3

Unfortunately, Greta missed a golden opportunity to cut a deal with her nemeses. Imagine Greta continuing her speech with these words:

“Since we cannot count on you to act morally, let me propose bribing you to save the planet. Adopt a high global carbon tax. However, cut other taxes so, on balance, you are better off. My and future generations will pay higher taxes to service the deficits you run. And if you insist on helping yourself to the same degree as you help us, cut your other taxes by enough to make that happen.”

Can today’s and tomorrow’s world uniformly gain from carbon taxation?

The ability to share the gains from taxing emissions, and not just across generations, but across regions,4 is inherent in the positive economics of externalities. We demonstrate this well-established, critically important, but routinely ignored point in three recent papers (Kotlikoff et al. 2021a, 2021b, 2021c). The papers feature life-cycle models populated by unashamedly selfish agents who do what comes naturally – burn fossil fuels to their pocketbook’s content with no regard to its future damage

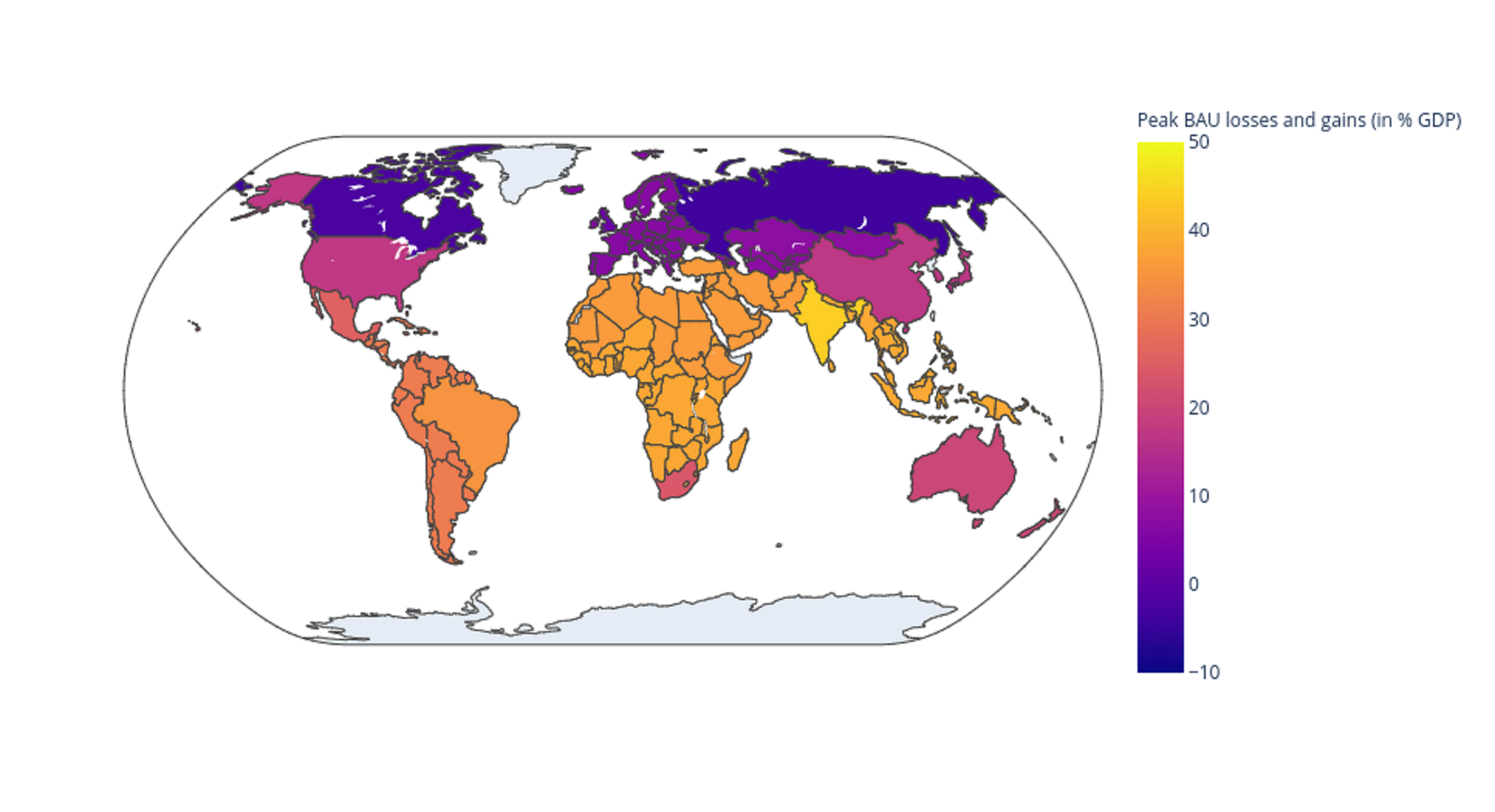

In particular, Kotlikoff et al. (2021c) features 18 regions and 80 overlapping generations living in each region. We model the relationship between carbon emissions and the global average temperature based on the latest climate science (Folini et al. 2021). Predicated average global temperature is used to determine, via pattern-scaling (e.g. Lynch et al. 2017, Kravitz et al. 2017 and references therein), region-specific temperatures. We posit a net damage function, which, like that of Krusell and Smith Jr (2018), permits cold regions to potentially benefit from climate change and hot regions to experience extreme damages. Our new damage function generates the same aggregate damages as in Nordhaus’s DICE model,5 given our updated climate module. However, unlike many other integrated assessment models, we incorporate the costly extraction of coal, oil, and gas and model clean energy production, taking account of its rapid rate of technological change. Without any carbon policy – that is, in the business as usual (BAU) scenario – many regions face a dire future. Figure 1 shows regions specific maximal future damages as a share of a region’s GDP.

Figure 1 Regional BAU losses and gains as percentage of GDP

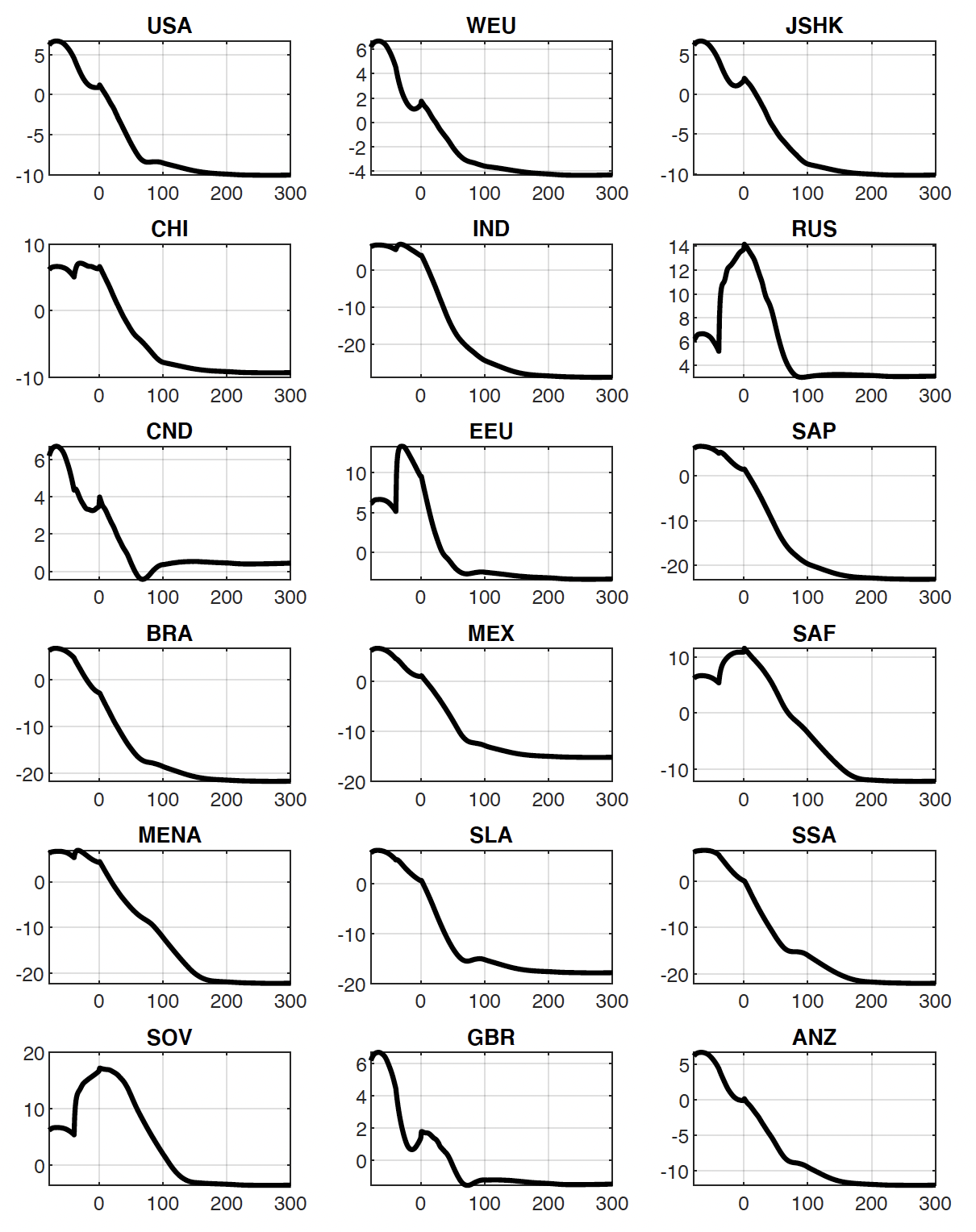

Our primary focus is determining the carbon policy that delivers present and future mankind the highest uniform percentage welfare gains (the uniform welfare-improving, or UWI, policy) – arguably the policy with the highest chance of global adoption. All agents, current and future, in all regions face lifetime net transfers that, in conjunction with the optimal UWI carbon tax path, generate the same percentage increase, measured as a compensating consumption differential, in full or remaining lifetime utility. The optimal policy comes with substantial transfers between generations and regions. Figure 2 shows net transfers over time for each region.

Figure 2 Net transfers as a share of the present value of remaining or full lifetime consumption in the 6x case (year 0 is 2017)

In our solution, regions that will suffer a lot from climate change make large transfers to northern regions, which suffer much less or even gain. Thus, our solution focuses on the transfers necessary to achieve a win-win in the presence of climate change. This entails particular generations in very poor regions, like India, making very large transfers (as a share of their consumption) because they gain the most from carbon taxation.6

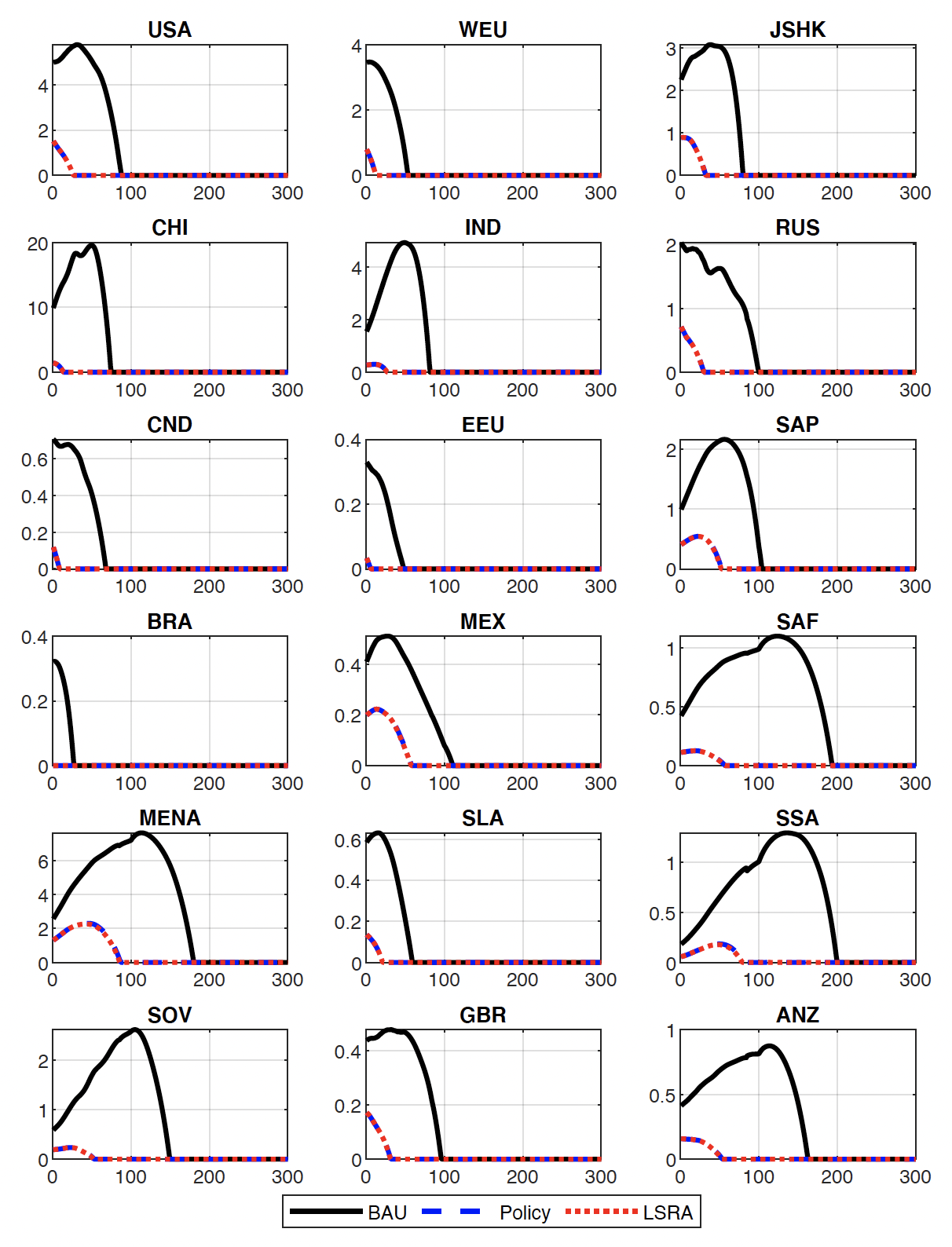

Our optimal UWI policy can deliver more than a 4% welfare gain to all of humanity. The optimal UWI carbon tax starts at roughly $100 per tonne of CO2 and rises, in real terms, at roughly 1.5% per year. The optimal UWI carbon-tax path rapidly ends coal production, roughly halves the duration of oil and gas production, reduces the peak global mean temperature increase by 1.5 degrees, and dramatically reduces climate damage. Figure 3 shows our model’s projected CO2 emissions in each region under the BAU scenario and under our optimal taxes. In our model, the decline of optimal emissions is dramatic in all regions.

Figure 3 Total CO2 emissions (measured in GtCO2) as a function of years (starting in 2017)

We also examine how much carbon taxes can improve without a global effort. It turns out that China’s participation in UWI carbon policy is crucial. Without it, peak global carbon damages will equal at least 60% of those under BAU. However, even if China, the US, and Europe jointly introduce taxes, the optimal UWI carbon policy fails to be very effective. The inability of subsets of regions to get close to the joint global optimum reflects, in large part, general equilibrium effects. When one region or a subset of regions imposes carbon taxes, they drive down the price of dirty energy. This, in turn, leads non-participating regions to increase their use of fossil fuels. This ‘Black Paradox’ is akin to the ‘Green Paradox’, which we also examine in our paper. Postponing the implementation of the optimal UWI tax until 2040, taking into account its growth, reduces the UWI gains from 4.35% to 2.73%. Delay reduces maximum UWI gains and increases emissions during the period of delay not only relative to immediate policy implementation, but also relative to engaging in no policy. For example, 2030 carbon emissions are 13% higher than under BAU.

Concluding remarks

To conclude, economists have, however inadvertently, inserted moral sentiment into resolving the gravest of economic externalities. They did this by first positing a social planner and then justifying that assumption by assuming something at full odds with man-made climate change – that current generations are intergenerationally altruistic, indeed, that they care, at the margin, as much about future generations as they care about themselves. This practice – adopted for, it seems, computational ease – has kept climate policy, as advanced by most economists, hostage to ethics. In so doing, it has fostered a generational war. Far worse, it has effectively vanquished analysis as well as discussion of the compensation (bribes, if you will) needed to enact meaningful carbon taxation. It is past time to set aside explicit and implicit irreconcilable debate over intergenerational fairness and let economics do what it’s designed to do – guide the sharing of gains and, in the process, get everyone on board to fix the problem.

References

Abel, A and L J Kotlikoff (1994), “Intergenerational Altruism and the Effectiveness of Fiscal Policy: New Tests Based on Cohort Data”, in Savings and Bequests, MIT Press.

Altonji, J G, F Hayashi, and L J Kotlikoff (1992), “Is the extended family altruistically linked? Direct tests using micro data”, The American Economic Review 82(5): 1177–1198.

Altonji, J G, F Hayashi, and L J Kotlikoff (1997), “Parental altruism and inter vivos transfers: Theory and evidence”, Journal of Political Economy 105(6): 1121–1166.

Barro, R J (1974), “Are government bonds net wealth?”, Journal of Political Economy 82(6): 1095–1117.

Bosetti, V, C Cattaneo, and G Peri (2020), “Should they stay or should they go? Climate migrants and local conflicts”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 619–651.

Boskin, M J and L J Kotlikoff (1985), “Pubic debt and us saving: A new test of the neutrality hypothesis”, Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Castells-Quintana, D, M Krause, and T K J McDermott (2020), “The urbanising force of global warming: the role of climate change in the spatial distribution of population”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 531–556.

Conte, B, K Desmet, D K Nagy and E Rossi-Hansberg (2021), “Local sectoral specialization in a warming world”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 493–530.

Cruz, J-L and E Rossi-Hansberg (2021), The Economic Geography of Global Warming.

Folini, D, F Kubler, A Malova, and S Scheidegger (2021), “The climate in climate economics”.

Grimm, M (2019), “Rainfall risk, fertility and development: evidence from farm settlements during the American demographic transition”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 593–618.

Hayashi, F, J Altonji, and L J Kotlikoff (1996), “Risk-sharing between and within families”, Econometrica 64(2): 261–294.

Indaco, A, F Ortega and S Tapınar (2020), “Hurricanes, flood risk and the economic adaptation of businesses”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 557–591.

Kotlikoff, L J, F Kubler, A Polbin, J Sachs, and S Scheidegger (2021a), “Making Carbon Taxation a Generational Win-Win”, International Economic Review 62(1): 3–46.

Kotlikoff, L J, F Kubler, A Polbin, and S Scheidegger (2021b), “Pareto-Improving Carbon-Risk Taxation”, Economic Policy, eiab008.

Kotlikoff, L J, F Kubler, A Polbin, and S Scheidegger (2021c), “Can Today’s and Tomorrow’s World Uniformly Gain from Carbon Taxation?”, NBER Working Paper 29224.

Kravitz, B, C Lynch, C Hartin, and B Bond-Lamberty (2017), “Exploring precipitation pattern scaling methodologies and robustness among CMIP5 models”, Geoscientific Model Development 10(5): 1889–1902.

Krusell, P and A A Smith, Jr (2018), “Climate change around the world”, presentation at the ifo Institute workshop on “Heterogeneous Agents and the Macroeconomics of Climate Change”, Munich, 14–15 December.

Lynch, C, C Hartin, B Bond-Lamberty and B Kravitz (2017), “An open-access CMIP5 pattern library for temperature and precipitation: description and methodology”, Earth System Science Data 9(1): 281–292.

Nordhaus, W D (1979), The efficient use of energy resources, Yale University Press.

Nordhaus, W D (2017), “Revisiting the social cost of carbon”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114(7): 1518–1523.

Peri, G and F Robert-Nicoud (2021), “On the economic geography of climate change”, Journal of Economic Geography 21(4): 487–491.

Ramsey, F P (1927), “A contribution to the theory of taxation”, The Economic Journal 37(145): 47–61.

Stern, N H (2007), The economics of climate change: The Stern review, Cambridge University Press.

Endnotes

1 See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stern_Review.

2 See, for example, Boskin and Kotlikoff (1985), Altonji et al. (1992), Abel and Kotlikoff (1994), Hayashi et al. (1996), and Altonji et al. (1997). But one need not consult the evidence to know that today’s single, married, and partnered agents have a singular interest – themselves. Were that not the case – were our world chock full of intergenerationally altruistic, Ramsey (1927), Barro (1974)-type agents, they would, long ago, have unanimously chosen leaders to enact meaningful climate policy.

3 https://www.npr.org/2019/09/23/763452863/transcript-greta-thunbergs-speechat-the-u-n-climate-action-summit.

4 Somewhat connected to our study is also the work by Krusell and Smith Jr (2018), Cruz and RossiHansberg (2021), as well as a recent series of papers in a recent special issue of the Journal of Economic Geography (Peri and Robert-Nicoud 2021) that discusses how climate change yields heterogeneous effects across space, and also points out geographic mobility as one key element of human adaptation (Conte et al. 2021, Castells-Quintana et al. 2020, Indaco et al. 2020, Bosetti et al. 2020, Grimm 2019, as well as https://voxeu.org/article/economic-geography-climate-change).

5 DICE was originally termed by Nordhaus (1979) and is an abbreviation of ‘Dynamic Integrated Model of Climate and the Economy’.

6 The normatives will claim this unfair. Why should poor future Indians pay for a problem not of their making even if, percentage-wise, they benefit the same? That is a good question, but not one economics cannot resolve. What it can do is show the cost of, for example, exempting all generations of Indians from making net compensation payments. We plan such an analysis in future work.