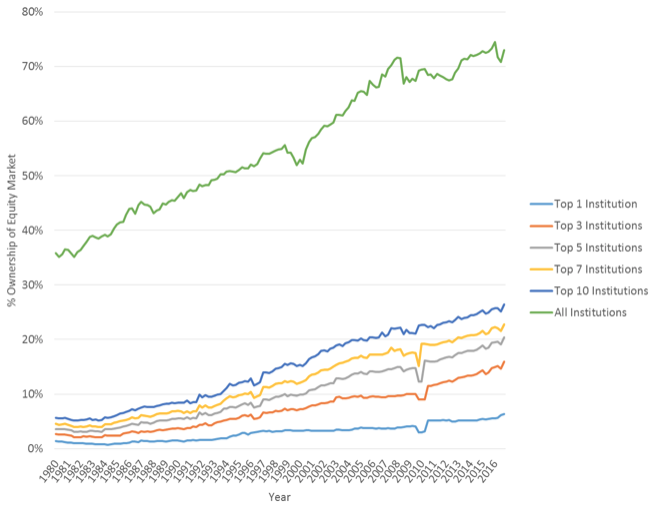

Recent decades have witnessed the rise of large institutional players in financial markets. Since 1980, the top ten institutional investors have quadrupled their holdings in US stocks. As of December 2016, the largest institutional investor oversaw 6.3% of total equity assets, and the top ten investors managed 26.5% of these assets (see Figure 1).

Observing these trends, regulators have expressed concerns about systemic risks that could result from this high concentration of assets in a few large actors. The main threat is that institutional investors, when experiencing redemptions, liquidate their portfolios and destabilize asset prices. The effect may thus propagate to other investors’ balance sheets.1 However, these potential implications of large institutional investors on prices of stocks they hold remain unclear and unexplored.

Figure 1 Time series of large institutions’ ownership

Note: The figure shows the aggregate equity holdings by all institutions and the top institutions over time, as a percentage of total market capitalisation of the US equity market.

What are the implications of large institutional ownership on stock prices?

Theoretical arguments suggest that large institutions should affect stock prices more than small institutions. Gabaix (2011) posits that large market players are ‘granular’, i.e. shocks to these agents are not easily diversified when aggregating across units and are reflected in aggregate market outcomes. In particular, aggregate fluctuations can result from firm-level shocks if the distribution of firms is fat-tailed.2

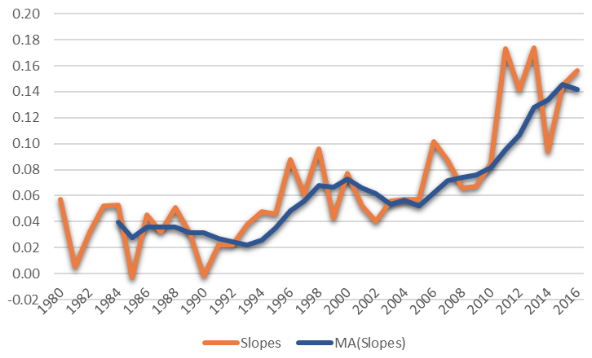

Drawing inspiration from these theories, Itzhak Ben-David, Rabih Moussawi, John Sedunov and I undertake an empirical study of the impact of large institutional ownership on stock prices in the US market (Ben-David et al. 2019). We show that ownership by large institutions increases volatility in the underlying securities, and that this increase reflects a rise of noise in stock prices. The economic magnitude of this effect grows over time, coinciding with the rise of the importance of large institutions in financial markets (see Figure 2). Towards the end of the sample period the effect is economically large: a one-standard deviation increase in the largest ten institutions’ ownership is associated with 16% of a standard deviation increase in volatility. While our main tests focus on daily volatility, the effect is also present at lower frequencies (weekly, monthly, quarterly), making it relevant for long-term investors as well.

Figure 2 Annual estimates

Notes: The figure presents slope coefficients and moving averages of slope coefficients from Ordinary Least Squares. The dependent variable is a stock’s Daily volatility, which is computed from daily returns during a given quarter. The key independent variable, which is presented below, is the coefficient on Top institutional ownership, which is the fraction of a stock’s capitalisation held by the top ten institutional investors in the market. The slopes are expressed in standard deviation units of the dependent variable for a one standard deviation change in top ten institutions’ ownership. The sample period is 1980/Q1–2016/Q4.

To address the potential endogeneity of institutional ownership, we exploit a natural experiment originating from the merger of two large institutional investors in 2009. Arguably, this is an exogenous event relative to the determinants of volatility. Securities in the portfolio of the smaller institution are, after the merger, owned by the top institution in the market. We therefore expect their volatility to increase. Indeed, we find a significant increase in post-merger volatility as a function of pre-merger ownership by the smaller firm (the treatment variable).

One might speculate that the increase in volatility that we identify is a desirable outcome of institutional ownership. For example, large institutions could encourage information production and faster price discovery. To shed light on this issue, we investigate whether large institutions are associated with more efficient prices. In fact, focusing on the autocorrelation in daily returns, we find that stocks with higher ownership by top institutions display more negatively autocorrelated returns. This evidence is consistent with the idea that large institutions impound liquidity shocks into prices, which then revert, and lead to noisier prices.

To conclude our analysis of the influence of large institutions on asset prices, we directly address the regulatory concerns mentioned earlier and study the effect of large institutional investors on stock prices during periods of market turmoil. Given our conjecture that large investors influence asset prices through a more intense demand for liquidity, we expect the prices of the stocks that they own to be more fragile when aggregate liquidity is low. Accordingly, we find that in turmoil periods, stocks with higher ownership by large institutions experience significantly lower returns, while no effect on the level of returns is present in normal times.

What is driving the effects on stock prices?

In the second part of our study, we also investigate the potential drivers of the asset pricing effects that we identify. We ask whether different units within a large asset management firm display more correlated behaviour than independent asset managers. The within-firm correlation, in turn, would prevent diversification of idiosyncratic shocks, causing a larger impact of these shocks on asset prices. We investigate several channels. First, intuitive arguments suggest that the various asset managers in the same institution may experience more correlated capital flows than independent entities. For example, institutions typically cultivate a brand name, and therefore affiliated entities are perceived as sharing the destiny of the broader family. Similarly, distribution policies and cross-selling practices (e.g. funds that are offered in company pension schemes) may increase flow correlation. Consistent with this conjecture, we find that the correlation of flows of mutual funds within the same family is significantly higher than that of independent funds.

Second, investment choices may be correlated for asset managers who operate under the same institution. Institutions often rely on a centralised research division that generates investment views that inform trading decisions across the family. Thus, even though different asset managers have leeway in their portfolio allocation, their behaviour may display abnormal correlation due to the family-wide investment directions. Two pieces of evidence support this conjecture. First, portfolio rebalancing trades are also significantly more correlated for mutual funds in the same family. Second, entities within the same group trade on a smaller set of stocks relative to the investment universe of independent firms, which is consistent with an overlap in investment strategies within the same family.

Finally, we show that trades by large institutions are bigger than those of a synthetic control group made of independent firms with the same total assets as the large institution. This evidence is also consistent with the granularity of large institutional investors. It suggests that different units within the same firm are more likely to trade in the same direction, so that their trades do not cancel out. This finding can explain why trading intensity on stocks owned by large institutions is more pronounced and prices of these securities are more volatile, noisier, and more fragile.

What are the implications for regulatory design?

Our results have implications for regulatory design. In particular, they inform the debate about the optimal size of an asset management firm. Regulators have been questioning the systemic implications of large asset managers. We show that combining different institutions within a unique conglomerate affects the ‘production function’ of all the entities that are involved. The access to capital as well as the investment and trading activities of the different components within a conglomerate display higher correlation than for independent firms. This correlated behaviour, combined with the sheer size of the conglomerates, has repercussions on asset price stability that is mostly felt at times of market stress. Especially the last consideration supports the mentioned regulatory concerns and suggests that excessive concentration in the asset management industry may be harmful from the point of view of systemic risk.

Of course, any regulatory action should weigh the decrease in price efficiency and the increased potential of large price drops against the economies scale in information production and trading that large institutions can achieve and can pass on to their clients. The ultimate impact on welfare of large institutional investors remains an open question for future research.

References

Acemoglu, D, V M Carvalho, A Ozdaglar and A Tahbaz‐Salehi (2012), “The network origins of aggregate fluctuations”, Econometrica 80(5): 1977-2016.

Ben-David, I, F Franzoni, R Moussawi, J Sedunov (2019), “The granular nature of large institutional investors”, CEPR Discussion Paper No 13427.

Blank, S, C M Buch and K Neugebauer (2009), “Shocks at large banks and banking sector distress: The banking granular residual”, Journal of Financial Stability 5(4): 353–373.

Bremus, F, C M Buch, K Russ and M Schnitzer (2018), “Big banks and macroeconomic outcomes: Theory and cross-country evidence of granularity”, Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking 50(8): 1785–1825.

Corsetti, G, A Dasgupta, S Morris and H S Shin (2004), “Does one Soros make a difference? A theory of currency crises with large and small traders”, Review of Economic Studies 71: 87–113.

Financial Stability Board (2015), “Assessment methodologies for identifying non-bank non-insurer global systemically important financial institutions”, Consultative document.

Gabaix, X (2011), “The granular origins of aggregate fluctuations”, Econometrica 79(3): 733–722.

Kelly, B T, H N Lustig and S Van Nieuwerburgh (2013), “Firm volatility in granular networks”, NBER Working Paper No. 19466.

Office of Financial Research, US Department of the Treasury (2013), Asset Management and Financial Stability, Technical report.

Endnotes

[1] The Office of Financial Research (2013) identifies redemption risk as a major vulnerability of asset managers, and points to the fire sale channel as a source of systemic risk. Relatedly, a recent Financial Stability Board (2015) publication remarks that, although research studying market contagion is abundant, a gap exists in the study of the potential effect of large individual organisations.

[2] A growing body of economic literature studies the impact of granularity in several contexts. Acemoglu et al. (2012) and Kelly et al. (2013) study the effects on supply chains. Blank et al. (2009) and Bremus et al. (2018) study the effects of granularly large banks on the banking industry. Corsetti et al. (2004) develop a model that explains the impact of one large trader on the behaviour of small traders.