In May 2022, the cover story of The Economist (2022), “The coming food catastrophe”, described a daunting scenario where the war on Ukraine has hit a global food system that was already weakened by Covid-19, climate change, and energy shocks. That same day, the Executive Director of the UN World Food Programme, David Beasley, declared that the Ukraine conflict would be a “declaration of war on global food security” and would “cause famine, destabilization and mass migration in nations around the world”. Meanwhile, the UN secretary-general warned against “the spectre of a global food shortage”.

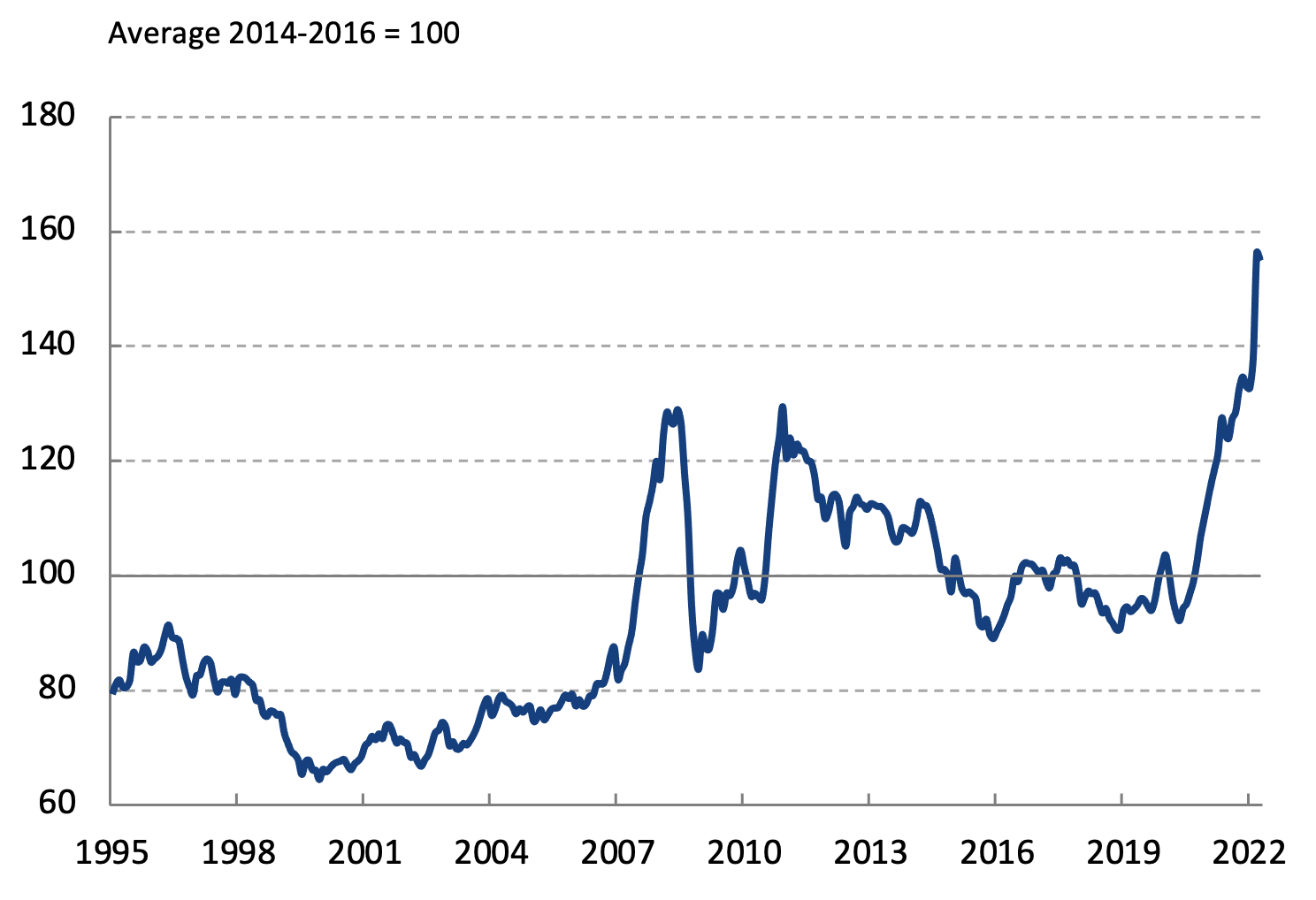

According to the World Food Programme, in less than one year, the population exposed to high food prices and financial difficulties has risen to 1.6 billion people. Up to 345 million people are estimated to suffer from acute food insecurity (United Nations 2022a, 2022b). Although the situation has partially reverted in the last months, since 2020 food prices have risen steeply, and the FAO food price index is currently at historical record high levels (see Figure 1). Food crises, which aggravate poverty and inequality issues in developing countries and poorer households (Artuc et al. 2022), are likely to trigger migration flows. Indeed, the European Commission has expressed concerns about the “huge challenge” posed by migration waves sparked by food shortages. In parallel, the number of applicants for political asylum has increased during the past two decades (Hatton 2021), and the war in Ukraine casts a daunting shadow on refugees in Europe (Becker 2022).

Figure 1 FAO Food price index in real terms

Source: FAO

The link between food crises and migration seems clear to policymakers. However, existing studies on international migrations have generally overlooked the role of food crises, with a few exceptions. In a recent study (Carril-Caccia et al. 2022), we aim to understand better the effects of food crises on international migration flows. Is a potential global food crisis expected to trigger mass migrations? Where would those flows be directed?

In order to answer these questions, we apply the empirical framework of the structural gravity model of trade (Yotov et al. 2016) to data on asylum seekers with origin in 114 developing countries and destinations in 155 countries – both developed and developing.

The link between food insecurity and migration

Modelling catastrophic events like food crises within the gravity framework is challenging for several reasons. Firstly, the standard models of migration flows weigh the payoff of migrating (e.g. higher salaries and well-being) against the costs of moving (e.g. monetary or psychological). Food crises could affect migrations in two opposing ways. On the one hand, they increase the payoff of migrating since food crises reduce the well-being of the migrant in their country of origin and “push” migrants out of their countries or regions. Additionally, migration insures against natural disasters (Yang and Choi 2007). On the other hand, since food prices increase during severe food crises, potential migrants may need to use more resources to cover their immediate food needs, limiting their ability to meet the costs of migrating (Smith and Floro 2020). Indeed, financial constraints have consistently been found to restrain internal and international migration flows (Angelucci 2015).

We hedge these limitations in two ways. Primarily by measuring the severity of the food crises with an index of the intensity of food crises. We built a new dataset (available upon request) with detailed data on the characteristics of food crises (e.g. intensity, causes). We processed and categorized the reports and unstructured information provided by FAO’s Global Information and Early Warning System (GIEWS). We developed a taxonomy of keywords to measure the impact of a food crisis event, its intensity, and its underlying causes. For consistency with the FAO’s classification, we used three levels: i) exceptional shortfall in aggregate food production/supplies (mild), ii) severe localised food insecurity (moderate), and iii) widespread lack of access (severe). Additionally, we distinguish the effect by the level of development of the host country, which is correlated with the level of moving cost.

The second challenge is empirical: food crises are country-specific and come at odds with the canonical econometric specification of the gravity equation (e.g. Baier and Bergstrand 2007), which delivers consistent estimates only of country-pair variables. To overcome this issue, we rely on recent developments in the gravity literature that exploit internal trade to identify country-specific policy variables (Heid et al. 2021). Thus, we constructed a migration dataset that includes internal displacements, migration flows within the same country, and international displacements.

The effects of food crises on international migrations: The intensity and causes matter

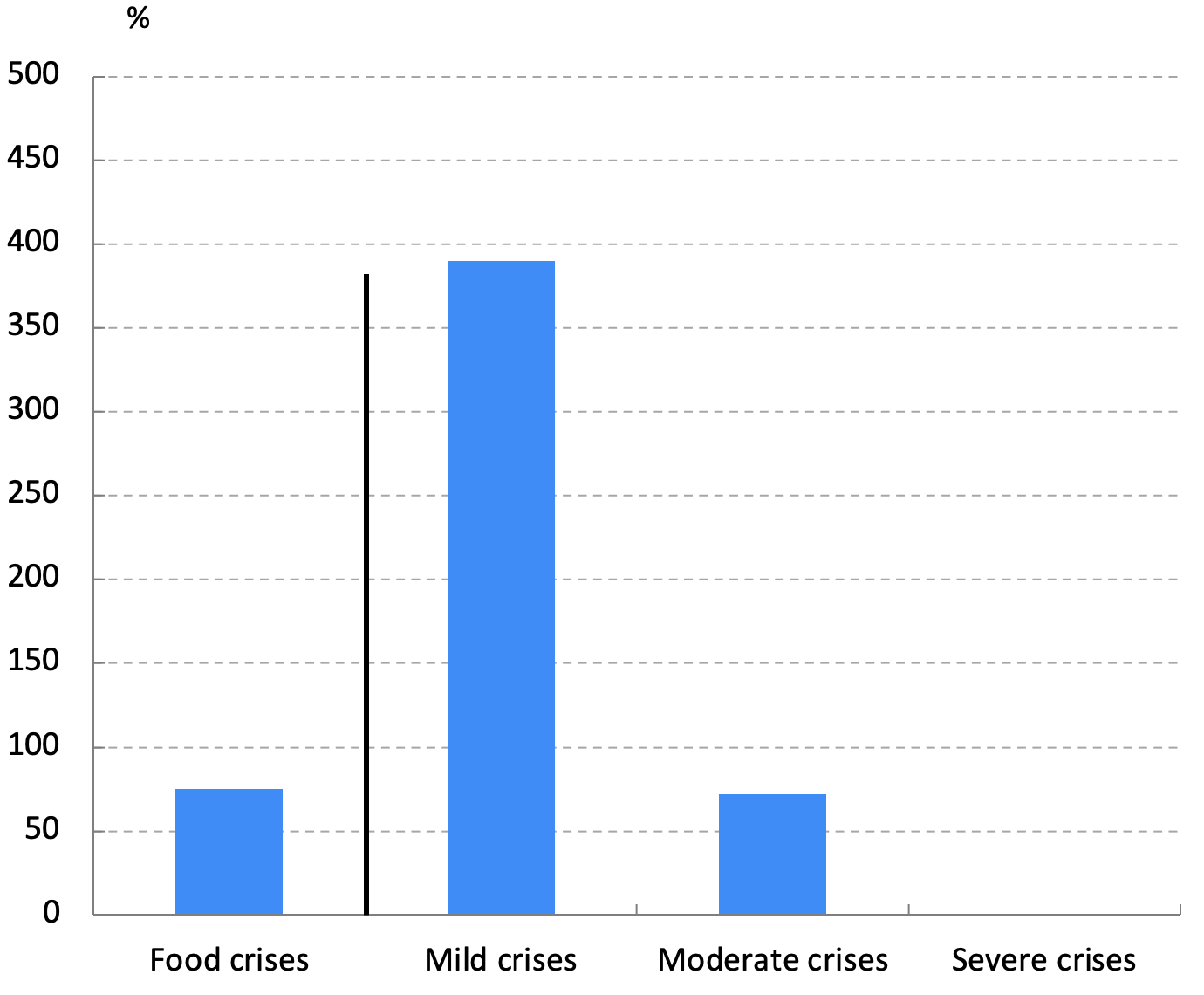

Results in Figure 2 suggest that overall food crises propel international migrations, leading to a substantially higher increase in the number of international forced migrants (75% more) than in the number of internal (i.e. within country) displacements.

In a second step, we distinguish between the severity of the crises. We find that mild food crises show the largest impact on the number of international displaced people (relative to internal displacements). In contrast, as the level of food insecurity increases, the positive effects moderate, and the increase in the number of international migrants tends to pair with the increase in internal displacements (see Figure 2). This suggestive evidence aligns with the hypothesis that the intensity of food crises correlates with financial constraints on migration. During mild food crises, individuals face fewer financial restrictions for international migration than during severe food crises, so migrants may still be able to afford the higher cost implied by cross-border (international) migrations. Recently, Cinque and Reiners (2022) showed that origin-country households tend to experience greater harm from natural disasters when unable to migrate.

Figure 2 Effects of food crises by intensity (compared with internal displacements)

Source: The authors' calculations draw on FAO’s Global Information and Early Warning System data. Note: The bars depict the marginal effects calculated with the coefficients of the gravity models’ estimates. When the coefficient is not significant, the bar appears in a lighter blue shade.

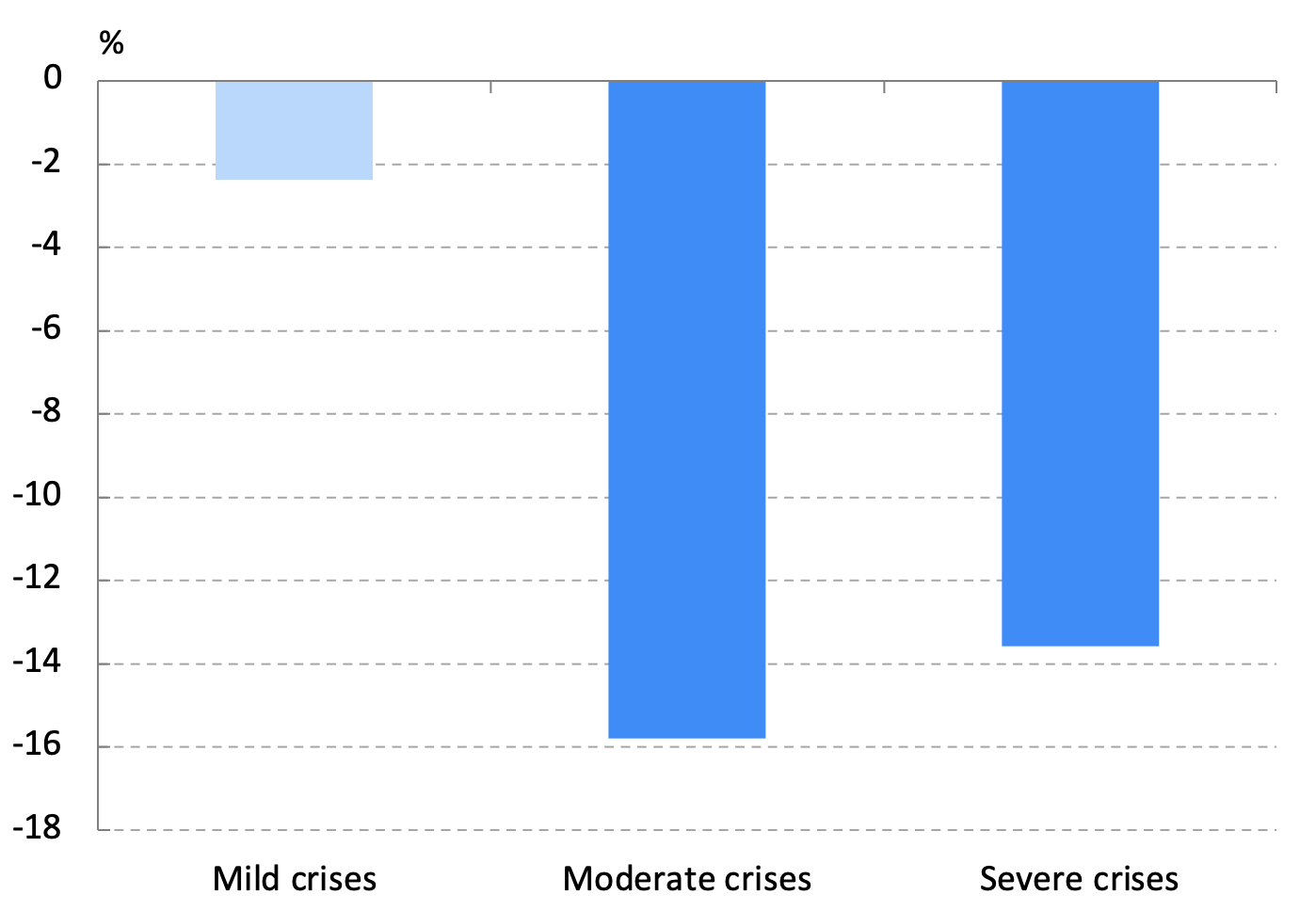

When we estimate the effect of food crises on the development level in the host country, we obtain a similar picture. Migration from less to more developed countries is more costly than between less developed countries due to higher travel costs, red tape, and restrictive migration policies. The findings in Figure 3 show that, on the one hand, mild crises have a similar impact on forced migration flows towards developing and developed countries. On the other hand, with severe or moderate food crises, forced international migrants are less likely to move to developed countries. In line with previous results, that could suggest that when food crises are severe, migrants may lack the necessary resources to afford the higher cost of migrating to a developed nation, thus choosing a developing destination.

Figure 3 Effects on flows to developed countries (compared with developing countries)

Source: The authors' calculations draw on FAO’s Global Information and Early Warning System data. Note: The bars depict the marginal effects calculated with the coefficients of the gravity models’ estimates. When the coefficient is not significant, the bar appears in a lighter blue shade.

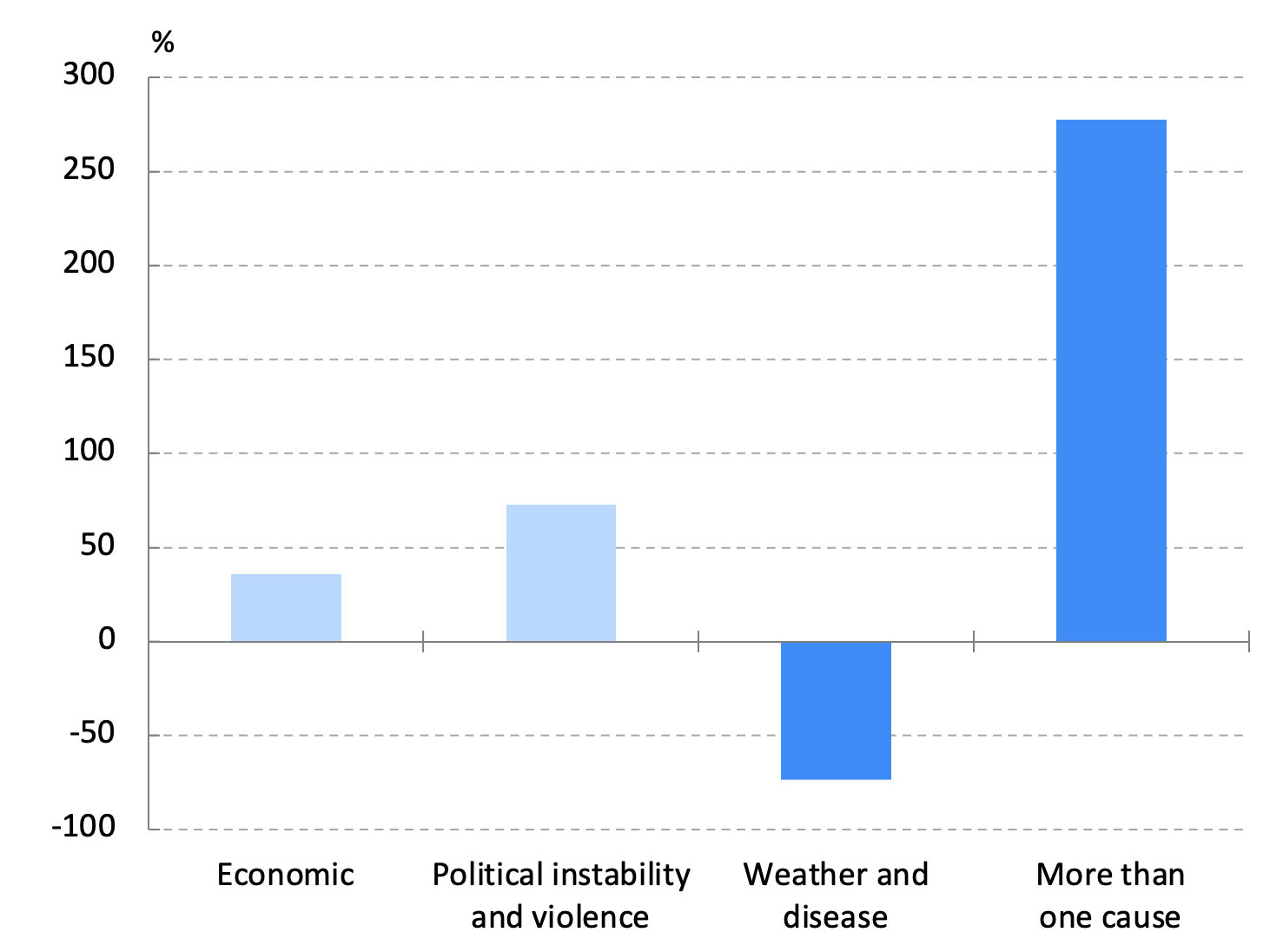

We also characterised the food crises according to their underlying causes in Figure 4. Food crises driven by more than one cause, which might be expected to last longer or be systemic, prompt larger forced international migratory flows (compared with internal displacement flows). By contrast, crises relating to adverse weather events and disease, usually more transitory, trigger more internal displacement flows. These results suggest that the expected persistence of the food crises might play a role in forced migration.

Figure 4 Effects of food crises by the underlying cause

Source: The authors' calculations draw on FAO’s Global Information and Early Warning System data. Note: The bars depict the marginal effects calculated with the coefficients of the gravity models’ estimates. When the coefficient is not significant, the bar appears in a lighter blue shade.

Concluding remarks

The rising concerns of a global food shortage call for a better understanding of its economic effects. Policymakers designing policies to mitigate the effects of food crises might find helpful insights in our study to anticipate the coordination across different countries and developing agencies. For example, focusing efforts within countries during severe food crises and extending them internationally during mild food crises. Additionally, food relief policies that mitigate the severity of a food crisis without stopping it might have the unintended consequence of increasing international migration flows.

References

Angelucci, M (2015), “Migration and Financial Constraints: Evidence from Mexico”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 97(1): 224-228.

Artuc, E, G Falcone, G Porto and B Rijkers (2022), “War-induced food price inflation imperils the poor”, VoxEU.org, 1 April.

Baier, S L and J H Bergstrand (2007), “Do free trade agreements actually increase members' international trade?”, Journal of international Economics 71(1): 72-95.

Becker, S (2022), “Lessons from history for our response to Ukrainian refugees”, VoxEU.org, 29 Mar.

Carril-Caccia, F, J Paniagua and M Suárez-Varela (2022), “Forced migration and food crises”, Banco de España Working Paper No 2227.

Cinque, A and L Reiners (2022), “Confined to Stay: Natural Disasters and Indonesia's Migration Ban”, CESifo Working Paper No. 9837.

Hatton, T (2021), “Asylum-seeker recognition rates and EU asylum policy”, VoxEU.org, 19 Nov.

Heid, B, M Larch and Y V Yotov (2021), “Estimating the effects of non‐discriminatory trade policies within structural gravity models”, Canadian Journal of Economics/Revue canadienne d'économique 54(1): 376-409.

The Economist (2022), “The coming food catastrophe”.

United Nations (2022a), “Brief No.3. Global impact of war in Ukraine: Energy crisis”.

United Nations (2022b), “Brief No.2. Global impact of the war in Ukraine: Billions of people face the greatest cost-of-living crisis in a generation”.

Smith, M D and M S Floro (2020), “Food insecurity, gender, and international migration in low- and middle-income countries”, Food Policy 91: 101-837.

Yang, D and H Choi (2007), “Are remittances insurance? Evidence from rainfall shocks in the Philippines”, The World Bank Economic Review 21(2): 219-248.

Yotov, Y V, R Piermartini and M Larch (2016), An Advanced Guide to Trade Policy Analysis: The Structural Gravity Model, WTO iLibrary.