The decades following the liberalisation of the banking industry in the US and Europe in the 1990s – a period featuring numerous domestic and cross-border bank mergers, a rapid pace of financial innovation, and an explosion of international linkages – also saw large fluctuations in sovereign yield spreads. The large swings in sovereign spreads were frequently synchronous, as spreads rose and fell in tandem across different economies. Such co-movements can arise from common shocks to the economic fundamentals of the issuing countries, which affect the expected losses from a default, as well as from shocks that impact the investors’ valuations of sovereign debt. Among past columns on the Vox, Levy Yeyati and Williams (2010) study how global shocks – namely, changes in the US yield curve – drive sovereign spreads of emerging market economies. Daehler et al. (2020) examine the role of country-specific fundamentals.

In this column, we explore the interplay between sovereign and global financial risk and document that a substantial portion of the observed co-movement between sovereign spreads since the mid-1990s can be accounted for by financial risk factors, closely related to the risk appetite of global financial institutions. Global financial institutions such as large capital markets banks play a critical role in underwriting sovereign bonds to meet the demands of borrowing countries, as well as intermediating in the secondary markets where these securities are traded (Gennaioli et al. 2014, Morelli et al. 2021). Sharp moves in asset prices – unrelated to country-specific fundamentals – can significantly affect these institutions’ collateral values and true mark-to-market losses. The resulting concerns about solvency can reduce their risk-bearing capacity or appetite, leading to a synchronous repricing of sovereign debt and other risky assets, an onset of a ‘risk-off’ sentiment in popular parlance.

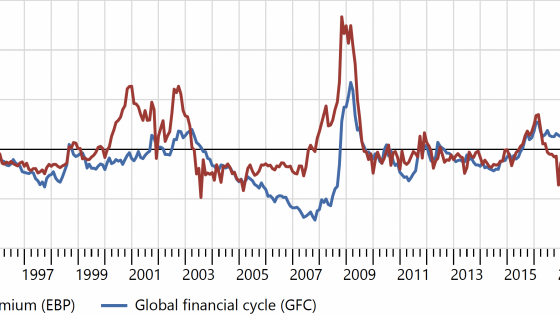

In a recent paper (Gilchrist et al. 2021), we formally analyse this sovereign-financial risk nexus using two measures of global financial risk: the ‘excess bond premium’ (EBP) of Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012) and the global financial cycle (GFC) factor of Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2020). As argued by Gilchrist and Zakrajšek (2012), the EBP – a US corporate bond credit spread net of default risk – provides a measure of the risk appetite among bank-affiliated dealers, institutions that play a crucial role in the pricing of most credit-related assets that are actively traded. The GFC factor proposed by Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2020), by contrast, is a latent factor that explains a significant portion of the variation in risky asset prices on a global scale.

Figure 1 shows these two financial risk factors – standardised for the ease of comparison – since January 1990. In addition to being positively correlated, both series are clearly countercyclical, rising sharply in periods of widespread financial distress.

Figure 1 Global financial risk factors

Source: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System; Miranda-Agrippino and Rey (2020).

To empirically examine how fluctuations in these two risk factors affect the dynamics of sovereign credit spreads, we construct a panel of dollar-denominated sovereign bonds traded in the secondary market. The panel contains nearly 1,800 individual securities issued by 53 countries, for which market prices were available during the 1995-2020 period. The two panels of Figure 2 display key features of these data: the central tendency of country-level credit spreads at each month-end, the median, and the corresponding cross-sectional dispersion of spreads, as measured by the interquartile range. Panel (a) focuses on bonds issued by countries having an investment-grade rating, while panel (b) covers countries rated as speculative grades.

Figure 2 Sovereign bond credit spreads

Note: The solid line in each panel shows the cross-sectional median of credit spreads on dollar-denominated sovereign bonds at month-end, while the shaded bands denote the corresponding interquartile ranges (i.e., Pctl75 – Pctl25).

Source: Refinitiv Eikon; authors’ calculations.

The substantial degree of dispersion in credit spreads across countries, in both segments of the market, indicates that country-specific factors are an important determinant of sovereign spreads at each point time. The role of financial risk factors is best seen by focusing on the years immediately preceding the 2008-09 financial crisis. The financial crisis is characterised by hefty risk appetite and buoyant investor sentiment, as evidenced by the unusually strong compression of sovereign spreads, in terms of both their levels and dispersion. As the cascade of shocks that roiled financial markets in 2008 eroded the confidence of investors and banks’ counterparties and seriously challenged the solvency of highly interconnected global financial institutions, sovereign credit spreads – concomitantly with the substantial increases in the EBP and the GFC factor – blew out across the credit-quality spectrum.

But do fluctuations in these financial risk factors influence the dynamics of sovereign spreads more generally? And if so, how persistent are their effects? To answer these questions, we use panel local projection methods to trace out the impact of shocks to the two financial risk factors on sovereign spreads, controlling for global, country-, and bond-specific determinants of spreads. Figure 3 plots the average response of the investment-grade and speculative-grade sovereign spreads to unanticipated shocks of one standard deviation to the EBP (panels (a) and (b)) and the GFC factor (panels (c) and (d)), respectively. The two shocks are, by construction, uncorrelated with the contemporaneous movements in the standard global factors that can drive sovereign spreads, as well as with country- and bond-specific controls.1

Figure 3 The impact of global financial risk on sovereign bond credit spreads

Note: The solid lines in panels (a) and (b) show the estimated responses of sovereign credit spreads to a one standard deviation orthogonalized shock to the EBP, while the solid lines in panels (c) and (d) show the responses of sovereign credit spreads to a one standard deviation orthogonalized shock to the GFC. The shaded band in each panel denotes the associated 90% confidence interval.

Source: Gilchrist et al. (2021).

An unanticipated one-time increase in the EBP of one standard deviation (roughly 25 basis points) has little effect on sovereign spreads upon impact, but the effect increases notably as the horizon grows (top row). For both investment-grade and speculative-grade sovereign spreads, the peak response occurs about 12 months after the impact of the EBP shock. In the case of investment-grade sovereign bonds, spreads widen about five basis points 12 months after the shock, whereas speculative-grade spreads increase about 15 basis points. It is worth noting that these peak responses are statistically different from zero at conventional significance levels and that their magnitudes are comparable to the responses of US corporate bond spreads to similarly identified EBP shocks documented in previous research.

A one standard deviation shock to the GFC factor, by contrast, has an economically large and statistically significant effect on sovereign spreads only in the near term, as the peak response in both segments of the market occurs within the first three months after the shock (bottom row). Note that the near-term economic effects of shocks to the GFC factor are comparable to the peak responses of spreads in the wake of the EBP shock. All told, our analysis indicates that a sudden onset of a risk-off sentiment – triggered by a reduction in the risk appetite of global financial institutions – leads to an economically significant and persistent widening of sovereign credit spreads, especially for riskier countries.

Motivated by this empirical evidence, we develop a theoretical framework, featuring linkages between the total intermediation capacity of the financial sector and sovereign debt risk premiums. In the model, the country’s choice of whether to default is endogenous, while the risk-bearing capacity of banks is governed by the tightness of their value-at-risk constraint as in Shin (2012). A tightening of this constraint – say, in response to an increase in aggregate uncertainty – reduces the risk appetite of the financial sector, forcing banks to deleverage and shrink their portfolios of sovereign bonds. The deleveraging pushes up the risk premium on sovereign bonds, inducing a significant widening of spreads. The rise in spreads boosts governments’ borrowing costs, which increases sovereign default risk, causing a further widening of sovereign spreads and a tightening of the banks’ value-at-risk constraint.

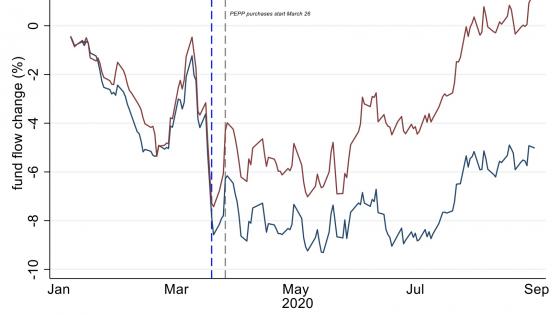

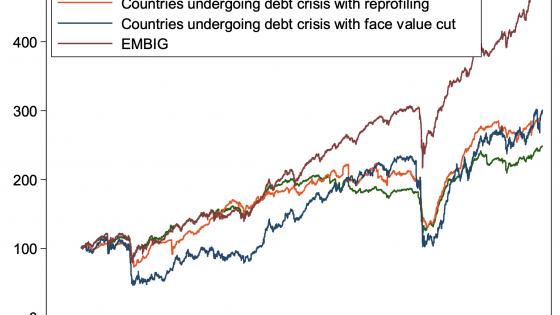

All told, we show that a substantial portion of the co-movement between sovereign credit spreads since the mid-1990s is accounted for by fluctuations in global financial risk. These effects are more pronounced and persistent when we measure global financial risk using the excess bond premium, a proxy for the risk appetite of major broker-dealers that are key players in the U.S. corporate bond market. Given the important role of global banks in today’s financial system, our theoretical framework also offers a useful perspective through which to view financial market disruptions that occurred in March 2020 with the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic (e.g. Moench et al. 2021).

Authors’ note: The views expressed are our own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank for International Settlements or the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

References

Daehler, T B, J Aizenman, and Y Jinjarak (2020), “Emerging market sovereign spreads and country-specific fundamentals during COVID-19”, VoxEU.org, 15 November.

Gennaioli, N, A Martin, and S Rossi (2014), “Sovereign Default, Domestic banks, and Financial Institutions,” Journal of Finance 69(2): 819–866.

Gilchrist, S and E Zakrajšek (2012), “Credit Spreads and Business Cycle Fluctuations,” American Economic Review 102(4): 1692-1720.

Gilchrist, S, B Wei, V Z Yue, and E Zakrajšek (2021), "Sovereign Risk and Financial Risk’,’ CEPR Discussion Paper No. 16750 (forthcoming in the Journal of International Economics).

Levy Yeyati, E and T Williams (2010), “Dangerous liaisons: US rates and emerging market spreads”, VoxEU.org, 13 January.

Miranda-Agrippino, S and H Rey (2020), “U.S. Monetary Policy and the Global Financial Cycle,” Review of Economic Studies 87(6): 2754-2776.

Moench, E, L Pelizzon, and M Schneider (2021), “‘Dash for cash’ versus ‘dash for collateral’: market liquidity of European sovereign bonds during the COVID-19 crisis,” VoxEU.org, 23 March.

Morelli, J, P Ottonello, and D Perez (2021), “Global Banks and Systemic Debt Crises”, forthcoming in Econometrica.

Shin, H S (2012), “Global Banking Glut and Loan Risk Premium", IMF Economic Review 60: 155-192.

Endnotes

1 The standard global factors include the real two-year US Treasury yield, the 10y/2y US Treasury term spread, the S&P 500 stock market return, and the VIX, a popular measure of the risk on/off sentiment used by market participants. The country-specific economic fundamentals are captured by the three-month local stock and foreign-exchange returns, along with their respective realised volatilities computed over the past three months. Lastly, the bond-specific covariates include the bond’s duration, coupon, age, and par value, characteristics that can influence liquidity premia of debt instruments. All specifications also include country fixed effects, which control for the fact the average level of spreads differs significantly across countries. To obtain the ‘’orthogonalized’’ global financial risk shocks, we employ a recursive identification method, whereby global variables are ordered as follows: the real U.S. two-year Treasury yield, the 10y/2y U.S. Treasury term spread, the S&P 500 return, the EBP, the GFC factor, and the VIX. As a robustness check, we also consider an alternative ordering in which we flip the order of the EBP and the GFC factor in the baseline ordering. This alternative identifying assumption has a negligible effect on the results(see Gilchrist et al. (2021) for details).