Although many contributions in the literature document a positive relationship between population health and macroeconomic performance, the size of this return remains subject to debate (e.g. Acemoglu and Johnson 2007, Bleakley 2007, Weil 2007, Bleakley and Lange 2009, Aghion et al. 2011, Cervellati and Sunde 2011, 2012, Bloom et al. 2014). One reason for this debate is that economists apply two conceptually different methods for estimating the macroeconomic return to population health. Micro-based approaches aggregate the estimated effect of individual health on wages to the macroeconomic level. Macro-based approaches, by contrast, estimate an aggregate production function that decomposes human capital into its components, including population health.

While micro-based approaches document a moderate positive effect of health (Shastry and Weil 2003, Weil 2007), macro-based approaches find estimates that are either negative and close to zero (Caselli et al. 1996, Acemoglu and Johnson 2007, 2014, Hansen and Lønstrup 2015) or 2.5 to 18.5 times larger than micro-based estimates (Barro and Lee 1994, Barro 1997, Bloom and Williamson 1998, Gallup and Sachs 2001, Bloom et al. 2004, Sala-i-Martin et al. 2004, Lorentzen et al. 2008, Aghion et al. 2011, Bloom et al. 2014). This presents a micro-macro puzzle of the macroeconomic return to health. In Bloom et al. (2022), we resolve this puzzle by showing that the estimated direct effect of health on labour productivity is of similar size in both micro-based and macro-based approaches when holding constant the indirect effects of health, which are included in macro-based approaches only.

Direct and indirect macroeconomic effects of health

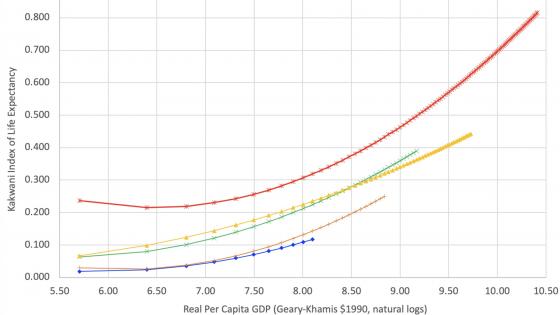

Health improvements influence the economy through many pathways. Most immediately is a direct effect of better health on worker’s productivity (Bloom and Canning 2002, Currie and Vogl 2012). However, many indirect effects also exist. Better health and higher life expectancy create incentives to invest in education (Cervellati and Sunde 2013) and in innovation (Prettner 2013). In addition, a rising life expectancy fosters saving and therefore physical capital accumulation (Bloom et al. 2007). Finally, better health, particularly that of women, reduces fertility and spurs an economic transition from stagnation toward sustained economic growth (Bloom et al. 2015, 2020).

Micro-based approaches estimate the macroeconomic return to health drawing on evidence of the effect of individual health on labour productivity in a Mincerian wage regression. In this regression, individual characteristics such as health, education, and experience determine labour productivity via the exponential function. Controlling for all effects apart from health, this regression uses individual-level data to estimate health’s direct effect on labour productivity—that is, the microeconomic return to individual health. The micro-based approach then aggregates the microeconomic return to individual health to derive the macroeconomic return to population health by summing over all individuals. Importantly, this approach captures health’s direct effect on labour productivity but not its indirecteffects, which are controlled for in the Mincerian wage regression.

Macro-based approaches, by contrast, decompose aggregate output – which equals aggregate income in a closed economy – into physical capital, human capital, and technology. Specifically, these approaches regress income growth on changes in population health and other control variables. This approach yields health’s direct effect if all indirect effects are comprehensively controlled for. Alternatively, it yields health’s total effect if the regression uses exogenous variation in population health that captures both health’s direct and indirect effects.

Reconciling micro-based and macro-based approaches

The previous discussion stipulates that micro-based and macro-based approaches deliver quantitatively similar results for health’s direct effect on labour productivity. In Bloom et al. (2022), we therefore set up a macro-based model that incorporates a Mincerian wage regression, so that we can compare our results of the macroeconomic return to health with the evidence of the micro-based approach. We estimate this model for a panel of 133 countries observed every five years from 1965 to 2015. Our specifications use within-country variation of population health as measured by the adult survival rate, controlling for past economic development, physical capital accumulation, secondary education, demographic structure, institutions, and time trends.

Our results document a positive effect of population health on income per capita. Likewise, the results for the other variables confirm the signs expected from theory. Lagged economic development exhibits a negative coefficient, which implies conditional convergence. In contrast, capital accumulation, growth of the working-age population, and secondary education promote income per capita. In extended specifications, we show the results’ robustness to the inclusion of additional controls, alternative specifications, and changes in sample composition and sample length. The estimated effect of adult survival on income per capita is quantitatively stable across all specifications and significantly different from zero throughout.

Consistency of micro-based and macro-based estimates

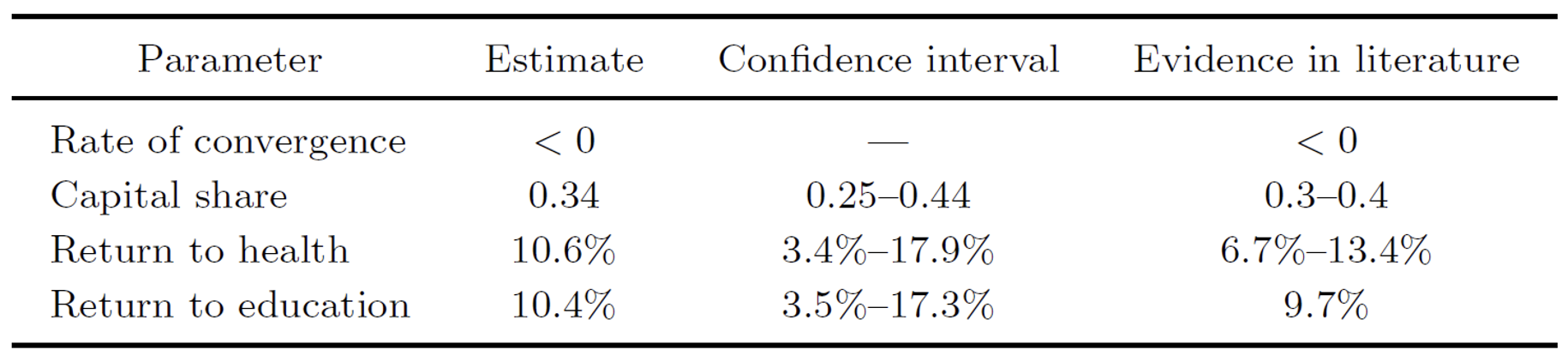

How do these estimates tie in with estimates from the micro-based approach? Table 1 compares our baseline results with those of Weil (2007), which show that an increase in the adult survival rate of ten percentage points raises labour productivity by 6.7% to 13.4% depending on the datasets used in the underlying Mincerian wage regression. Our results indicate that an increase in the adult survival rate of ten percentage points translates into a 10.6% increase in labour productivity (Bloom et al. 2022, p. 14), which falls in the range of plausible estimates reported by Weil (2007). Likewise, the 95% confidence interval of our estimate ranges from 3.4% to 17.9% and includes the plausible values implied by Weil’s (2007) evidence. Hence, the micro-based and macro-based estimates of the direct macroeconomic return to health are quantitatively similar, and the two different approaches are consistent with one another. Moreover, our estimates also match the stylised facts of the empirical literature on the remaining explanatory variables: the estimation results for the rate of convergence, the capital share, and the return to education are qualitatively and quantitatively consistent with evidence from previous empirical studies.

Table 1 Comparison of our estimates with the evidence in the literature

Conclusions

Our results reconcile the micro-based and macro-based evidence of the return to health by showing that the results of both approaches are consistent with one another. Therefore, they provide a rationale for using the micro-based approach to estimate the direct economic benefits of health interventions at the aggregate level. Furthermore, our results indicate that public health measures are an important lever for fostering economic development. Potential policies along these lines are vaccination programs, antibiotic distribution programs, and micronutrient supplementation schemes, which tend to lead to large direct improvements in health (World Bank 1993, WHO 2001, Field et al. 2009, Luca et al. 2018). In addition, policies that target the indirect effects of health on economic growth—such as birth control, family planning, and educational programs (Bloom et al. 2020, Kotschy et al. 2020) – could further promote economic development.

References

Acemoglu, D and S Johnson (2007), “Disease and development: The effect of life expectancy on economic growth”, Journal of Political Economy 115: 925–985.

Acemoglu, D and S Johnson (2014), “Disease and development: A reply to Bloom, Canning, and Fink”, Journal of Political Economy 122: 1367–1375.

Aghion, P, P Howitt and F Murtin (2011), “The relationship between health and growth: When Lucas meets Nelson-Phelps”, Review of Economics and Institutions 2: 1–24.

Barro, R J and J W Lee (1994), “Sources of economic growth”, Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 40: 1–46.

Barro, R J (1997), Determinants of economic growth: A cross-country empirical study, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Bleakley, H (2007), “Disease and development: Evidence from hookworm eradication in the American South”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 73–117.

Bleakley, H and F Lange (2009), “Chronic disease burden and the interaction of education, fertility, and growth”, Review of Economics and Statistics 91: 52–65.

Bloom, D E and D Canning (2002), “The health and wealth of nations”, Science 287: 1207–1209.

Bloom, D E, D Canning and G Fink (2014), “Disease and development revisited”, Journal of Political Economy 122: 1355–1366.

Bloom, D E, D Canning, R Kotschy, K Prettner and J Schuenemann (2022), “Health and economic growth: Reconciling the micro and macro evidence”, CEPR Discussion Paper 17393.

Bloom, D E, D Canning, R K Mansfield and M Moore (2007), “Demographic change, social security systems, and savings”, Journal of Monetary Economics 54: 92–114.

Bloom, D E, D Canning and J Sevilla (2004), “The effect of health on economic growth: A production function approach”, World Development 32: 1–13.

Bloom, D E, M Kuhn and K Prettner (2015), “The contribution of women’s health to economic development”, VoxEU.org, 9 October.

Bloom, D E, M Kuhn and K Prettner (2020), “The contribution of female health to economic development”, Economic Journal 130: 1650–1677.

Bloom, D E and J G Williamson (1998), “Demographic transitions and economic miracles in emerging Asia”, World Bank Economic Review 12: 419–455.

Caselli, F, G Esquivel and F Lefort (1996), “Reopening the convergence debate: A new look at cross-country growth empirics”, Journal of Economic Growth 1: 363–389.

Cervellati, M and U Sunde (2011), “Life expectancy and economic growth: The role of the demographic transition”, Journal of Economic Growth 16: 99–133.

Cervellati, M and U Sunde (2012), “Diseases and development: Does life expectancy increase income growth?”, VoxEU.org, 6 January.

Cervellati, M and U Sunde (2013), “Life expectancy, schooling, and lifetime labor supply: Theory and evidence revisited”, Econometrica 81: 2055–2086.

Currie, J and T Vogl (2012), “Lasting effects of childhood health in developing countries”, VoxEU.org, 15 November.

Field, W, O Robles and M Torero (2009), “Iodine deficiency and schooling attainment in Tanzania”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 1: 140–169.

Gallup, J L and J Sachs (2001), “The economic burden of malaria”, American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 64: 85–96.

Hansen, C W and L Lønstrup (2015), “The rise in life expectancy and economic growth in the 20th century”, Economic Journal 125: 838–852.

Kotschy, R, P Suarez Urtaza and U Sunde (2020), “The demographic dividend is more than an education dividend”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 117: 25982–25984.

Lorentzen, P, J McMillan and R Wacziarg (2008), “Death and development”, Journal of Economic Growth 13: 81–124.

Luca, D L, J H Iversen, A S Lubet, E Mitgang, K H Onarheim, K Prettner and D E Bloom (2018), “Benefits and costs of the women's health targets for the post-2015 development agenda”, In B Lomborg (ed.), Prioritizing development: A cost benefit analysis of the United Nations’ sustainable development goals, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 244–254.

Prettner, K (2013), “Population aging and endogenous economic growth”, Journal of Population Economics 26: 811–834.

Sala-i-Martin, X, G Doppelhofer and R I Miller (2004), “Determinants of long-term growth: A Bayesian averaging of classical estimates (BACE) approach”, American Economic Review 94: 813–835.

Shastry, G K and D N Weil (2003), “How much of cross-country income variation is explained by health?”, Journal of the European Economic Association 1: 387–396.

Weil, D N (2007), “Accounting for the effect of health on economic growth”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1265–1306.

WHO (2001), Macroeconomics and health: Investing in health for economic development, Geneva: Commission on Macroeconomics and Health, World Health Organization.

World Bank (1993), World development report 1993: Investing in health, Washington, DC: World Bank.