Despite the rapid expansion of internet access to households around the world, there are large disparities in children’s access to internet at home. Over 95% of 15-year-old students in OECD member countries report having a link to the internet at home (OECD 2017). In contrast, access to the internet continues to lag for children in developing countries. For example, less than half of 15-year-old students in Algeria, Peru, and Vietnam report having internet access at home (OECD 2017). In an effort to alleviate this ‘digital divide’, many governments and non-governmental organisations have invested substantial resources in expanding internet access to children in developing countries. Yet rigorous evidence for the impact of home internet access on children’s outcomes has been limited to developed countries and may not generalise to settings where fewer resources can complement or substitute for such technology.1

Consequently, it is important to understand whether internet access at home can stimulate learning for children in developing countries. Internet access may affect a range of skills, including academic achievement and cognitive skills. For example, if children lack educational materials, access to the internet could improve the development of academic skills by providing access to educational websites with subject-specific content and exercises, such as Khan Academy. Moreover, children might access e-books and other reading materials such as newspapers, blogs, and online encyclopaedias like Wikipedia. On the other hand, internet access may diminish learning if children spend more time on activities that are not conducive to developing academic skills, such as playing online games, and less time reading and doing homework. Finally, internet access may affect cognitive skills by exposing children to online activities that alter cognitive processes (Johnson 2006, Mills 2014).

The study

To measure the effects of providing internet access in a developing country context, we implemented a randomised experiment in Lima, Peru between 2011 and 2013 (Malamud et al. 2019). First, we provided access to XO laptops for home use to a random sample of 540 out of 2,457 children in June/July 2011.2 These children were enrolled in grades 3 to 5 of low-achieving public primary schools. Second, among children who received these laptops, we randomly selected about 350 children to receive free high-speed internet access in July/August 2012. The laptops included 32 applications selected by the Ministry of Education of Peru for its national programme, and we offered training and manuals on how to use them. We also offered tutorials and manuals to children who received internet access in which we showed them how to take advantage of freely available educational websites created by Peru’s Ministry of Education and other online resources, such as Khan Academy and Wikipedia.

To evaluate the impacts of our interventions, we conducted a follow-up survey in November 2012, approximately 17 months after the laptops were distributed and five months after the provision of internet access. We also conducted an additional follow-up survey in March 2013 to check for longer-run impacts after the summer vacation. We compare children who were randomly chosen to receive laptops with internet access (group 1) to those who only received laptops without internet access (group 2) and those who did not receive laptops at all (group 3). Thus, we are able to estimate the impact of internet access both separately from, and in conjunction with, the impact of the laptops themselves.

Main findings

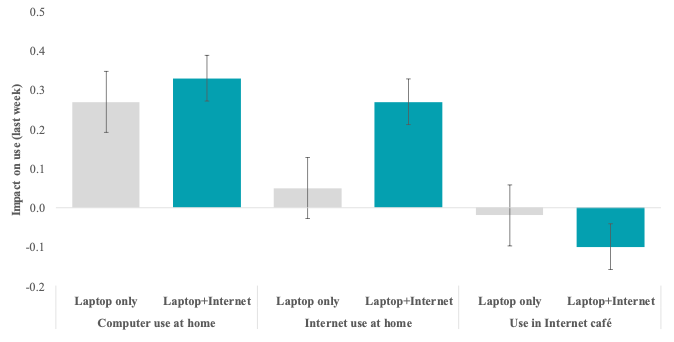

Our interventions were successful in increasing children’s use of technology at home and led to substantial improvements in digital skills. All of the figures below show the impact of our interventions on groups 1 and 2 relative to group 3, which did not receive laptops or internet access. Figure 1 shows that children offered laptops with internet access were about 25 percentage points more likely to use internet at home (in the week prior to being surveyed) compared to those who did not receive laptops and those who were offered laptops without internet. Interestingly, there was also some evidence of substitution away from internet use in internet cafes among children who were offered internet use.

Figure 1 Impact of access to home internet on technology use

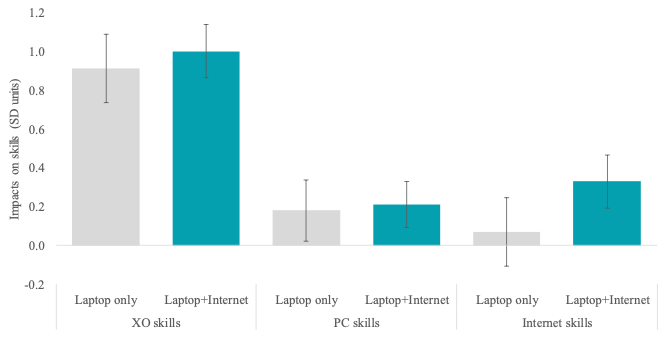

Furthermore, as shown in Figure 2, children who were offered laptops with internet access scored 0.3 standard deviations higher on a test of internet literacy than those who were not offered internet access or who were offered laptops without internet. They also scored one standard deviation higher on a test that measured proficiency on the XO laptop compared to those who were not offered laptops, but not significantly different from those children who were offered laptops without internet. In addition, children who were offered laptops (with or without internet) had significant improvements on a Windows-based computer test, suggesting that gains in computer literacy were not only limited to the specific XO platform but transferred to skills for using other types of computers.

Figure 2 Impact of access to home internet on digital skills

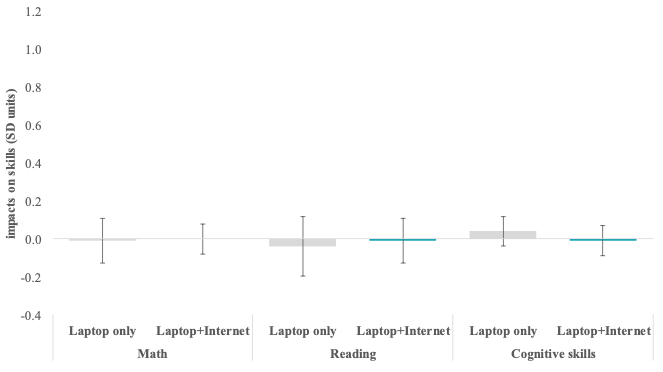

Despite the increase in the use of home technology and the improvements in digital skills, there were no significant effects of internet access on academic achievement. Figure 3 indicates that we can rule out impacts larger than 0.08 standard deviations in maths and larger than 0.13 standard deviations in reading with 95% confidence when comparing children who were offered internet access to those who did not get laptops. Nor were there any significant effects on an index capturing a broad set of cognitive skills, as measured by the Raven’s Progressive Matrices test, a verbal fluency test, a test of executive functioning, a coding test, a working memory test, and a test of spatial reasoning.

Figure 3 Impact of access to home internet on academic and cognitive skills

Similarly, we did not find significant effects on a self-esteem index measured by a self-reported questionnaire. Based on teacher reports, children in the treatment groups were equally likely to exert effort at school when compared with their counterparts in the control group, and there were no differences in grades obtained from administrative school records or in teachers’ perceptions of children’s sociability. There was also no evidence of improvements when we resurveyed children 8 to 9 months after internet provision following the summer vacation, despite the potential benefits of engaging children with the internet to counteract summer learning loss.

Discussion

Why were there no significant impacts on academic achievement and cognitive skills from providing children with internet access? Though we cannot provide a definitive answer to this question, we consider several possible explanations. First, while the intervention itself was not directly linked with pedagogical activities at school, we did provide children with tutorials and manuals to make more effective use of their computers and the internet for educational purposes. Second, although we do not have long-term outcomes, previous research has shown that new technology can have short-term impacts within a year (Malamud and Pop-Eleches2011, Banerjee et al. 2007) or even just several months (Muralidharan et al. 2016). Third, it is possible that the impact on internet use was not substantial enough. The provision of internet did lead to increases in use, as shown above, but we also observed a decline over time. Finally, it may be that children did not use the internet for educational purposes. Indeed, computer and internet logs reveal that use was focused more on entertainment than on learning. This happened despite our efforts to promote educational use through the provision of training, tutorials and manuals. Furthermore, data from time diaries suggest that there was some reduction in the time spent watching TV and doing homework.

Providing children with access to computers and internet at home, together with some training as we did in Peru, does close the gap in digital skills between those with and without home computers and internet. Therefore, to the extent that improving children’s digital skills is a relevant goal for an educational system, providing access to computers and internet at home may be one way to achieve this. However, it may also be possible to achieve these gains at a lower cost. For example, Bet et al. (2014) show sizeable increases in digital skills from relatively minor increases in access to shared computers at schools in Peru. Nevertheless, our analysis indicates that increased access to internet at home does not improve academic achievement, cognitive or socio-emotional skills, which are arguably the more important outcomes of such interventions. Thus, greater efforts must be made to help parents ensure that technological resources are used by children in ways that foster better educational outcomes.

You can read more about this topic on VoxDev, our partner website which focuses on research in development economics.

References

Banerjee, A, S Cole, E Duflo and L Linden (2007), “Remedying Education: Evidence from Two Randomized Experiments in India”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 122: 1235–1264.

Bet, G, J Cristia, and P Ibarrarán (2014), “The Effects of Shared School Technology Access on Students’ Digital Skills in Peru”, IDB Working Paper WP-476.

Faber, B, R Sanchis-Guarner, and F Weinhardt (2016), “ICT and Education: Evidence from Student Home Addresses”, NBER Working Paper No. 21306

Fairlie, R and J Robinson (2013), “Experimental Evidence on the Effects of Home Computers on Academic Achievement among Schoolchildren”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 5(3): 211–240.

Johnson, G (2006) “Internet Use and Cognitive Development: A Theoretical Framework” E-Learning 3(4): 565-573

Malamud, O and C Pop-Eleches (2011), “Home Computer Use and the Development of Human Capital”, Quarterly Journal of Economics 126: 987–1027.

Malamud, O, S Cueto, J Cristia, and D Beuermann (2019), “Do Children Benefit from Internet Access? Experimental Evidence from Peru”, Journal of Development Economics 138: 41-56

Mills, K L (2014), “Effects of Internet use on the adolescent brain: despite popular claims, experimental evidence remains scarce”, Science & Society 18(8): 385-387.

Muralidharan, K, A Singh, and A J Ganimian (2016), “Disrupting Education? Experimental Evidence on Technology-Aided Instruction in India”, NBER Working Paper 22923.

OECD (2017), PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being.

Vigdor, J, H Ladd and E Martinez (2014), “Scaling the Digital Divide: Home Computer Technology and Student Achievement”, Economic Inquiry 52: 1103–1119

Endnotes

[1] See Fairlie and Robinson (2013)and Vigdor et al. (2014) for evidence from the US, and Faber et al. (2016) for evidence from the UK.

[2] The XO laptops were developed by the One Laptop per Child (OLPC)programme with an emphasis on self-empowered learning and with specialised software intended to encourage such learning.