Since the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic, labour market indicators that traditionally move together have been sending very different signals about the amount of slack in the US labour market. Supply-side indicators like the prime-age employment-to-population ratio are still below pre-pandemic levels (79.5% in February 2022 versus 80.5% in February 2020), suggesting a modest degree of slack still in the labour market. On the other hand, demand-side indicators like the quits and vacancy rates have surged to record highs in recent months, indicating a very tight labour market.

The divergence between the supply-side and demand-side indicators has prompted debate over what measure should be used to assess labour market tightness. Some, such as Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell (2021), have suggested looking at employment indicators like the prime-age employment ratio to gauge labour market slack. Others have found that demand-side indicators like the vacancy-to-unemployment ratio (Barnichon and Shapiro 2022) or the quits rate (Furman and Powell 2021) are most predictive of wage inflation.

In our recent paper (Domash and Summers 2022), we use time-series and cross-section data to compare alternative labour market indicators as predictors of wage inflation. We compare four different slack indicators – the headline unemployment rate, the prime-age employment ratio, the vacancy rate, and the quits rate – and find that unemployment is a better predictor of wage inflation than the employment ratio, and that the vacancy and quits rate are roughly equivalent to the unemployment rate in explanatory power. We then construct a new indicator – firm-side unemployment – that ties together the unemployment rate with the vacancy and quits rates, and find that firm-side unemployment performs noticeably better than the unemployment rate at predicting wage inflation.

Labour market indicators have diverged significantly

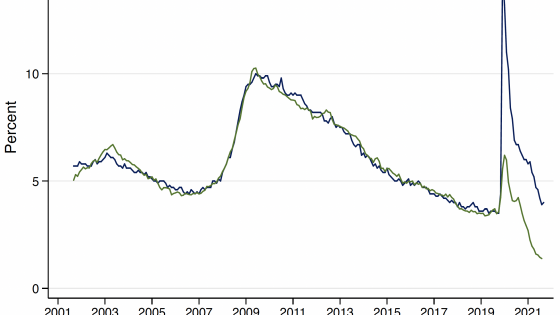

Figure 1 depicts Beveridge-type curves showing the relationship between supply-side and firm-side labour market indicators since 2001.

Figure 1 Relationship between firm-side vs household-side slack measures, January 2001 – December 2021

Historically, measures of slack on the supply side, like the unemployment rate and the prime-age (25-54) nonemployment rate (one minus the prime-age employment-to-population ratio), have moved in tandem with measures of slack on the demand side, such as the job vacancy and quits rates, meaning that different indicators gave broadly corroborative signals of labour market tightness. Figure 1 shows, however, that since the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, the supply-side indicators and the demand-side indicators have diverged significantly (depicted in orange).

These shifts in the Beveridge curves imply a higher level of job vacancies and quits for a given level of unemployment or non-employment. This raises the question: Are the supply-side or demand-side slack indicators more significant for predicting wage inflation?

Firm-side unemployment has dominant explanatory power for wage inflation

We use quarterly time-series and cross-section data between 1990 and 2019 to compare the explanatory power of different slack measures for wage inflation. Since data on job vacancies and quits from the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) are only available back to 2001, we use two alternative datasets to extend these series to 1990:

- For job vacancies, we use data constructed by Barnichon (2010), who makes use of the Help-Wanted Index published by the Conference Board to create a historical vacancy rate series from 1960 to 2001.

- For quits rates, we use quarterly job quits estimates from Davis et al. (2012), who construct a quarterly dataset of worker quits (DFH-JOLTS) by combining cross-sectional worker flow relations with data on the cross-sectional distribution of establishment growth rates.

We first document that the U-3 unemployment rate is better than the prime-age employment ratio in predicting wage inflation at the aggregate and state level, and that the job vacancy rate and the quits rate are comparable to the U-3 unemployment rate in their explanatory power. These findings hold across different wage series and time periods. We then estimate a firm-side equivalent unemployment rate by examining what unemployment rate is consistent with the current measures of the job vacancy rate and the quits rate. We regress the unemployment rate on the log of the vacancy rate and the log of the quits rate, using monthly data from the JOLTS from January 2001 to December 2019. We run several different model specifications, including different lag lengths, a time trend, and a structural break in July 2009. In general, all the models fit the data very well from 2001 to 2019, but show a clear break in the relationship after February 2020.

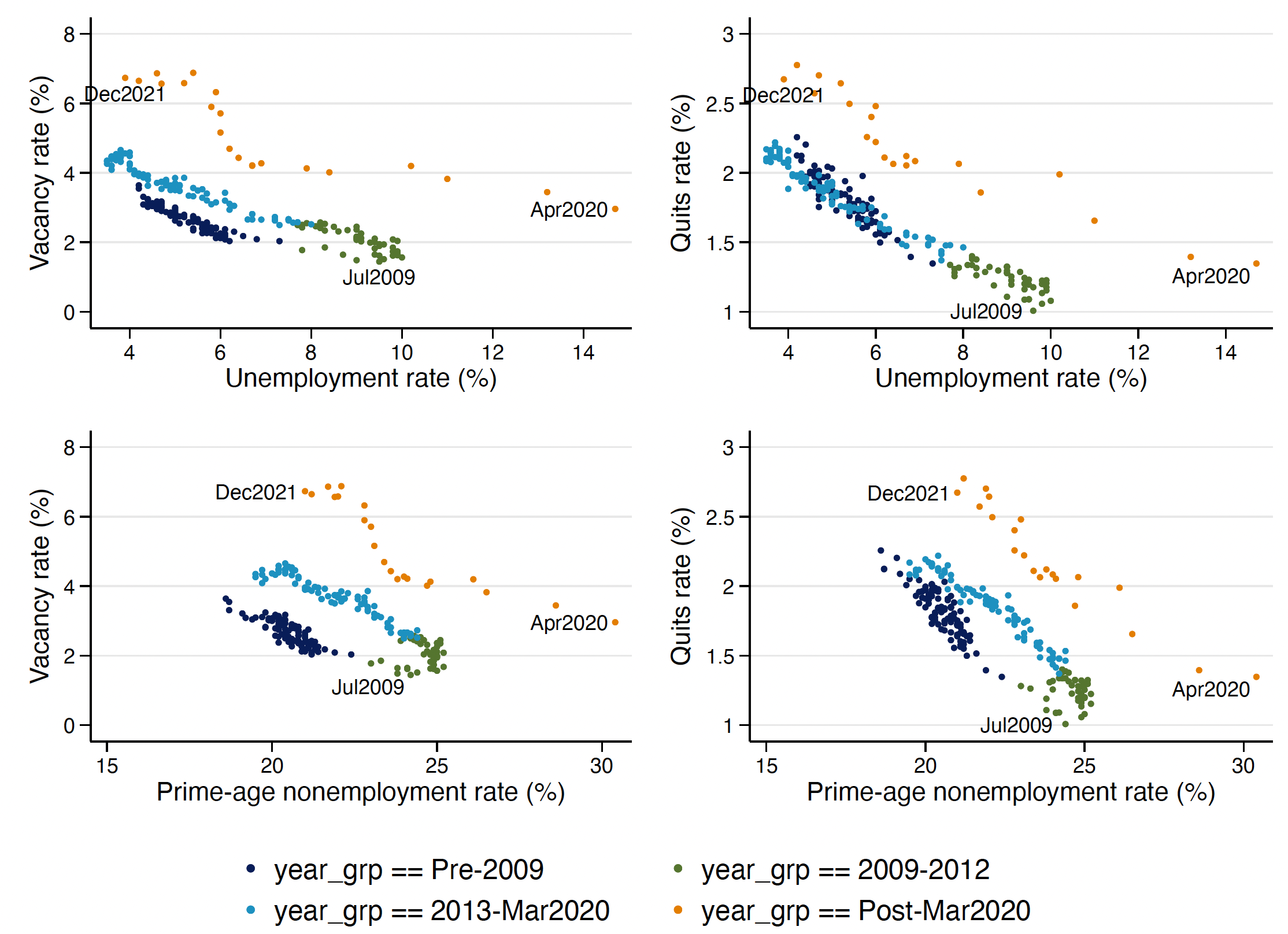

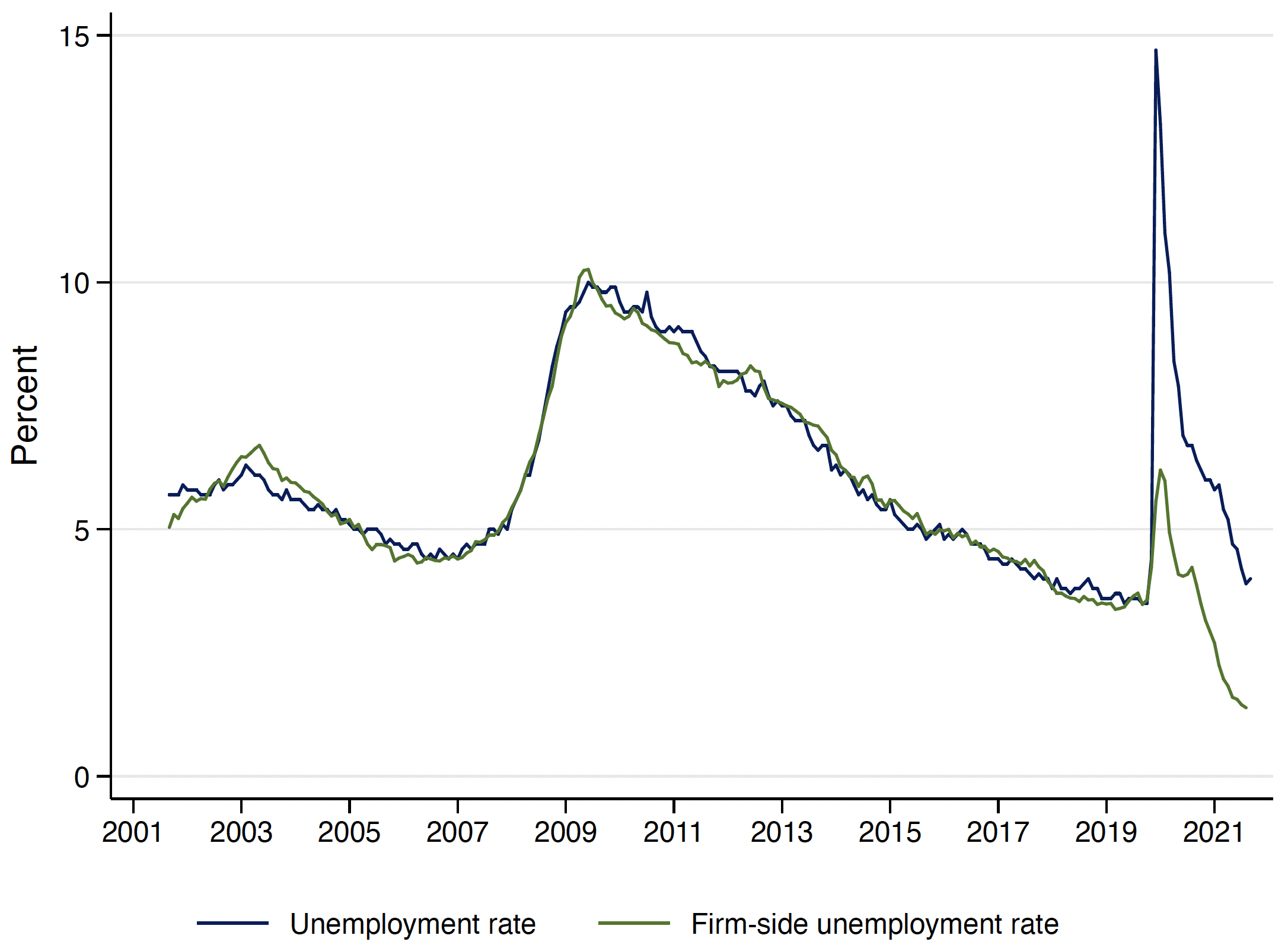

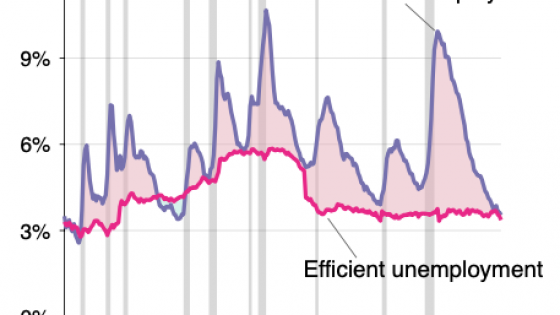

Figure 2 shows the relationship between the actual unemployment rate and the firm-side predicted unemployment rate, using a model with 12-month lags, a time trend, and a structural break. The predicted firm-side unemployment rate in January 2022 was between 1.3% and 1.7%.

Figure 2 Actual unemployment rate versus firm-side predicted unemployment rate

Using a wage Phillips curve model that includes the actual unemployment rate and our predicted unemployment rate as the regressors, we find that the firm-side predicted unemployment rate has essentially all the explanatory power in predicting wage inflation over the period 2001 to 2019. These findings are robust across 12 different model specifications that vary the wage series used to calculate nominal wage growth and the lag length of our explanatory variables. Moreover, the results also hold in cross-sectional data: at the state level, decreases in firm-side unemployment are more predictive of state-level wage growth than decreases in actual unemployment.

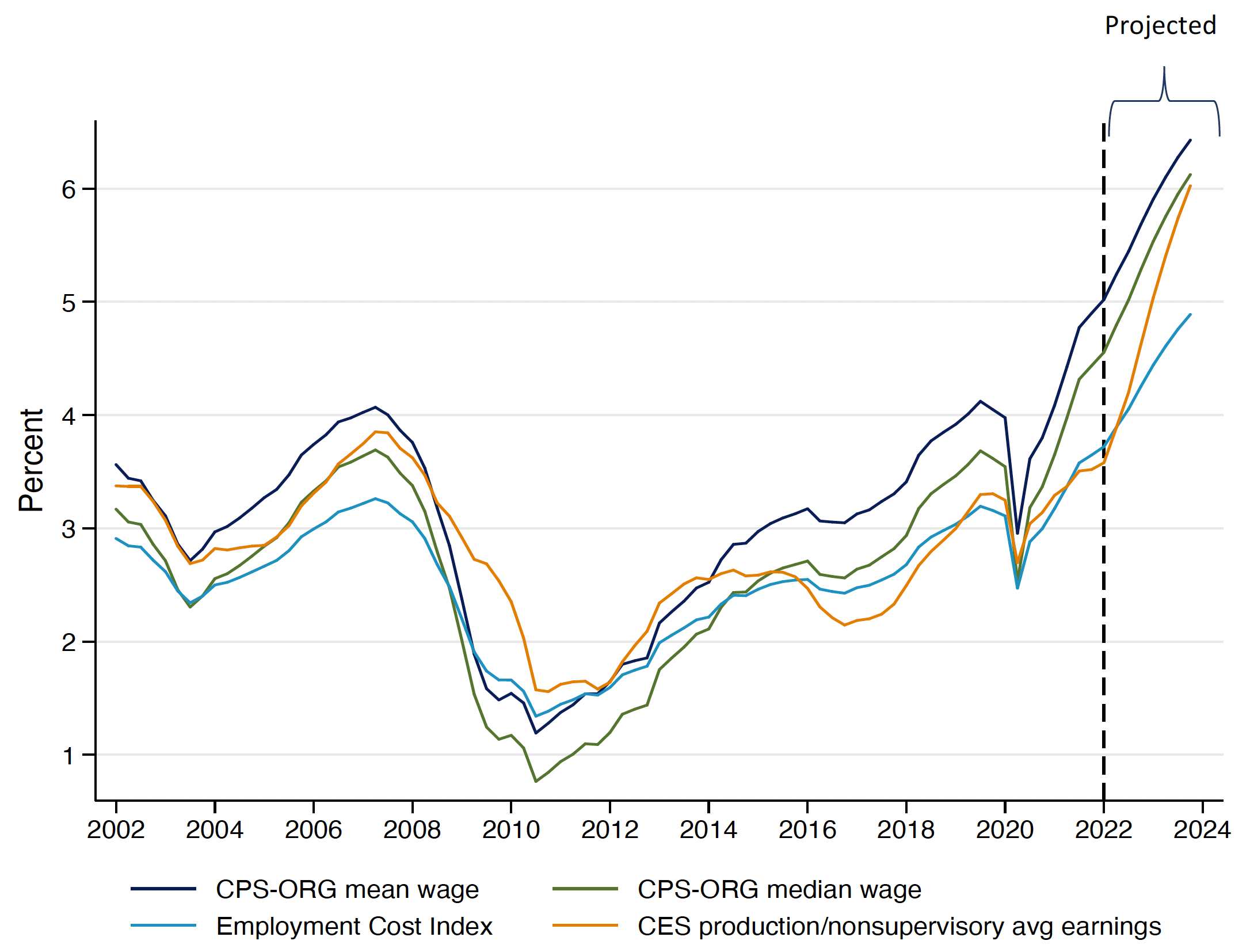

Given the extremely low firm-side predicted unemployment rate today, these results provide strong evidence that the current labour market is very tight. Firm-side predicted unemployment has fallen from an average of 3.6% in the fourth quarter of 2019 to an average of 1.5% in the fourth quarter of 2021, which corresponds to an increase in wage inflation from 4.0% to 4.9% (using CPS-ORG mean wages). Figure 3 shows estimates for nominal wage growth from a wage Phillips curve model using predicted firm-side unemployment as the slack variable and controlling for lagged inflation. The results indicate that estimated wage inflation in the fourth quarter of 2021 is the highest it’s been in the last 20 years across all four of our wage measures.

Figure 3 Predicted year-over-year nominal wage growth using firm-side unemployment as predictor variable

Outlook on labour market tightness moving forward

Some economists believe that labour market tightness will be alleviated over the coming year by increases in labour supply. We carry out a cursory analysis of the current labour shortfall, and estimate that labour force participation is likely to remain significantly depressed through at least the end of 2022, with excess retirements, Covid-19 health concerns, immigration restrictions, changes in workers’ tastes proxied by reservation wages, and shifts in the demographic structure explaining most of the labour shortfall.

Moreover, if employment were to increase due to an increase in labour force participation, it would be accompanied by increases in incomes, and therefore an increase in demand. We therefore believe that any benefits from the supply-side over the next year are unlikely to substantially mitigate inflation pressures from the labour market. Taken together, our research concludes that labour markets will likely continue to be very tight unless there is considerable slowdown in labour demand. These findings suggest to us the need for substantial caution about the possibility of inflationary pressures from the labour market moving forward.

References

Barnichon, R (2010), “Building a composite help-wanted index”, Economics Letters 109(3): 175-178.

Barnichon, R and A H Shapiro (2022), “What’s the Best Measure of Economic Slack?”, FRBSF Economic Letters 2022(4): 1-05.

Davis, S J, R J Faberman and J Haltiwanger (2012), “Labor market flows in the cross section and over time”, Journal of Monetary Economics 59(1): 1-18.

Domash, A and L Summers (2022), “How Tight are US Labor Markets?”, NBER Working Paper 29739.

Furman, J and W Powell III (2021), “”hat is the best measure of labor market tightness?”, Peterson Institute for International Economics blog post, 22 November.

Powell, J H (2021), “Getting Back to a Strong Labor Market”, speech at the Economic Club of New York (via webcast), 10 February.