In 2017, Mark Carney, then still governor of the Bank of England, and head of the Financial Stability Board, told us that:

“Over the past decade, G20 financial reforms have fixed the fault lines that caused the global financial crisis” (Carney 2017)

His claim was that the regulation put in place since 2008 had succeeded in making the financial sector less vulnerable to a systemic crisis.

In my book The Illusion of Control (Danielsson 2022), I argue the opposite. Despite the costly and onerous actions that regulation demands from participants in the financial system, a systemic financial crisis is now more likely than ever. Regulation has made us much better at managing fluctuations in today’s measured risk driven by external events, but at the expense of undervaluing the endogenous risk in the system that may lead to systemic crises. The false sense of security that results is an illusion of control.

Financial regulation is put in place to help us to manage the trade-off between safety and growth. Therefore, the primary objective of regulation is to maximise economic growth in a regulatory regime designed to adequately protect the people who use the system (microprudential regulation), and that does not give rise to too many crises (macroprudential regulation). A regulator might be tasked other objectives too that have little to do with growth – for example, protection of the environment. But encouraging economic growth will always be a regulatory goal.

But note that the objective of regulation is not to de-risk the economy, nor to achieve financial stability, nor to ensure compliance. Those are the instruments employed by a regulator.

Perceived risk and economic activity

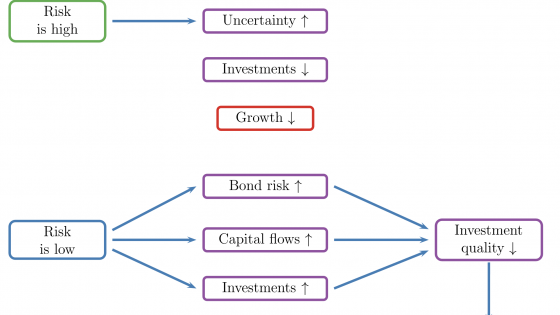

We know that, empirically, market sentiment about the level of risk matters for economic activity (Danielsson et al. 2022a, 2022b). When markets perceive risk to be high on a particular year, a reduction in capital flows and investment will slow growth in that year and the next year. When we perceive risk is low, capital flows and investment will boost growth in that year and the next year, but with a reversal after two years – nevertheless, the impact in this scenario is positive (There is an exception when credit growth has been excessive).

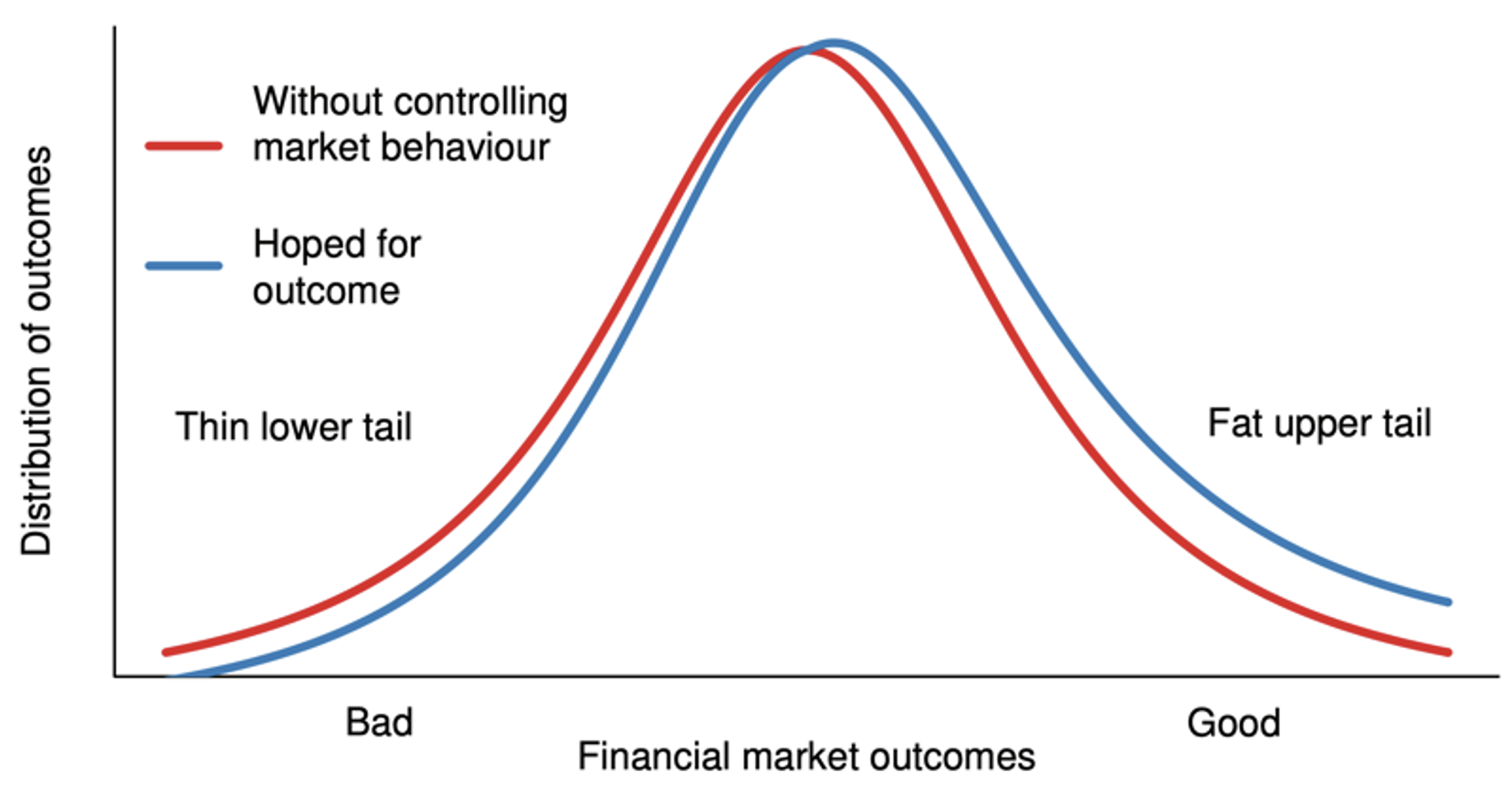

But how are these perceptions of risk formed, and what do they represent? Figure 1 shows a hypothetical representation of financial market outcomes (red curve), in which risk is the lower tail, and the regulator’s desired policy outcome (blue curve). The best solution to the control problem reduces the likelihood of bad outcomes – a thinner lower tail – and increases the likelihood of good outcomes.

Figure 1 Desired policy outcome for a financial regulator

Source: Author.

Risk in perception and reality

Regulators and private sector risk managers don’t just have a different view of how to do this: they often characterise the problem differently. Regulators tend to blame reckless yield-seeking by private investors; the investors often consider regulators to be over-focused on superficial measures of risk.

Who do we believe? Where we pin the blame for a crisis depends on how we measure the amount of risk in the system. We cannot observe risk directly, and so we must attempt to infer it using historical data on prices and events. There are many models for measuring risk, they all disagree, and there is no ex ante way to tell which is the most accurate. Yet we persist in the belief that actors in the market all have access to a single riskometer, a mythical device that can capture the true level of risk in the system and express it as a precise number (Danielsson 2011).

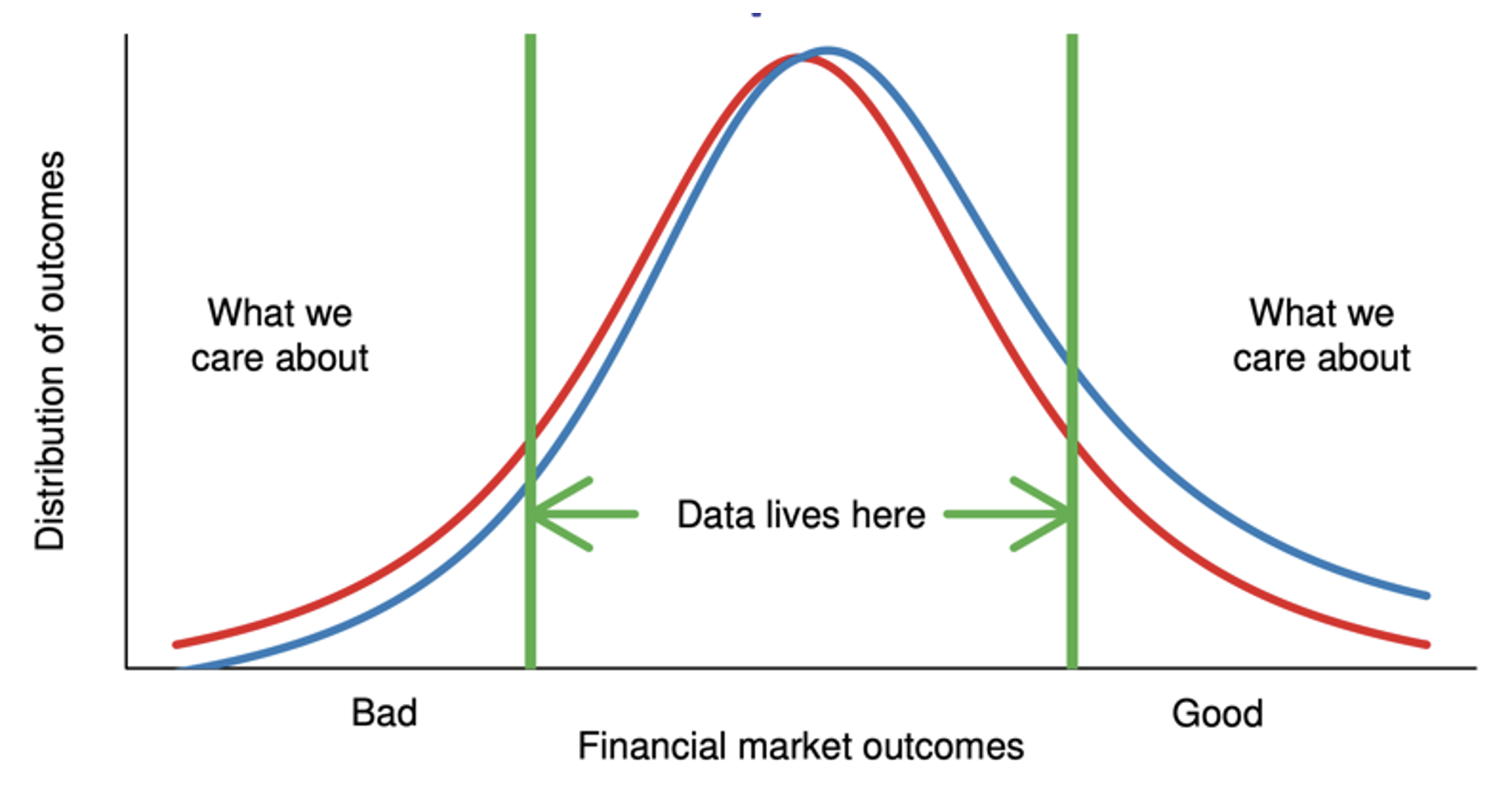

It is futile to try to construct an accurate riskometer. Any measure of risk, even if it captures historical data accurately at high frequency, suffers from the problem that almost all the data that is fed into the model maps the central portion of the curve (Figure 2), rather than the tails, which interest us. As a result, any projection of tail risk relies partly on the assumptions of the model’s builder, and so it would be rash to use them forecast systemic risk levels to more than one significant figure, though far more precision is common. Technically easy to do, but meaningless, creating misplaced confidence in the accuracy of the measurement.

Figure 2 Available data on financial market outcomes

Source: Author.

Also, different crises – such as those of 2008 and Covid-19 – have different drivers of risk, demanding different policy responses (Danielsson et al 2020). Crises occur in different places, at different times, and so it may be hard to learn much from history. Laeven and Valencia (2012) found that the typical OECD country suffers a systemic crisis only once in forty-three years, making it rather difficult to train the risk models.

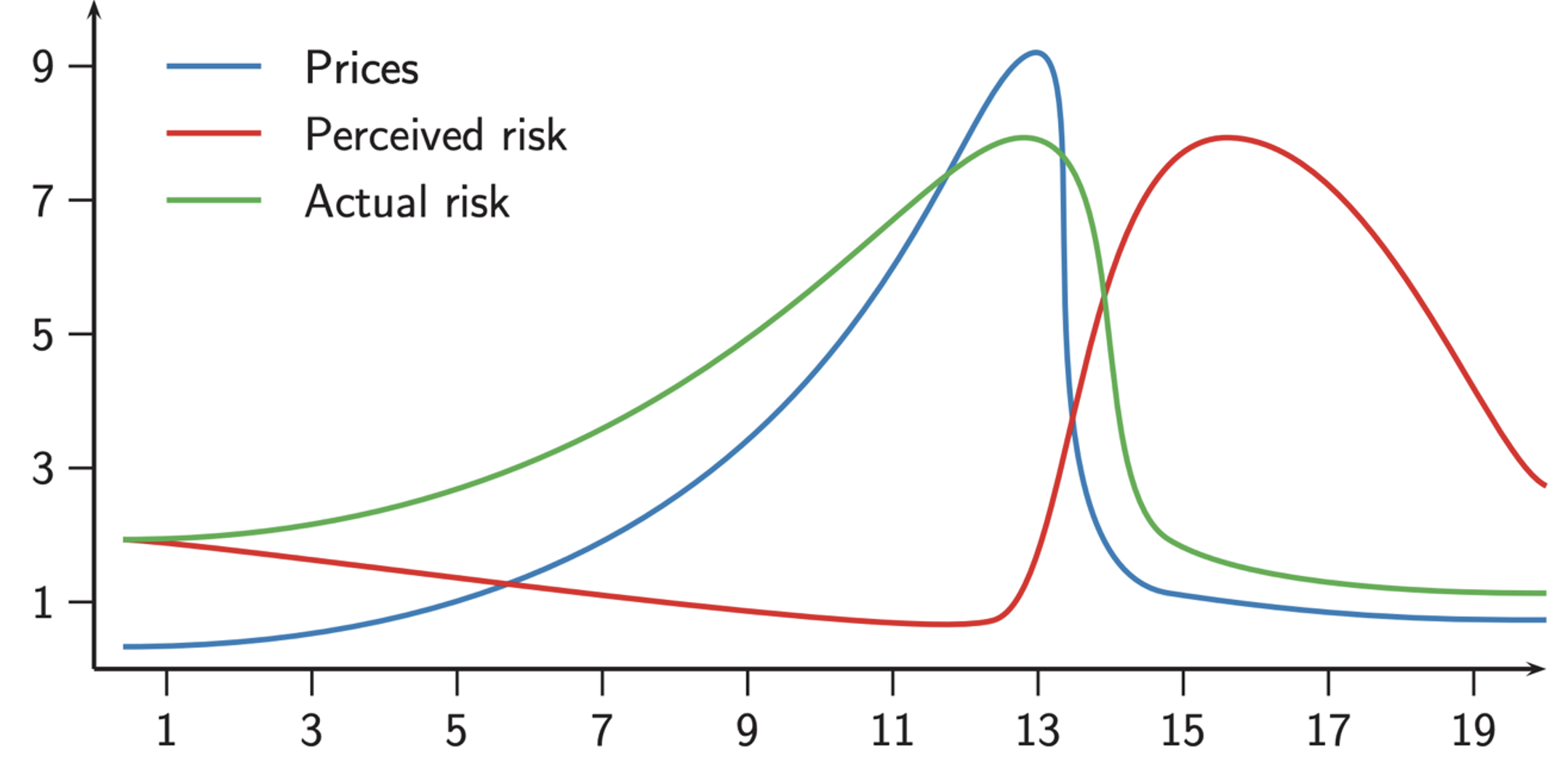

The build-up of risk in a system may take years or even decades of apparent calm. That calm itself may help to create systemic risk. In the words of Hyman Minsky (1986), “Stability is destabilising”. While risk builds up in a system, the models used by private investors will report a measure of risk that is uncorrelated with actual systemic risk. Figure 3 shows an example: a hypothetical price bubble. Steadily rising prices (blue) create a perception of risk (red) that misleads – the unobserved systemic risk is the green curve, which falls as prices drop (Danielsson et al. 2009).

Figure 3 A price bubble

Source: Author.

Bank risk forecast models underestimate risk before this type of crisis (they are seemingly earning money for nothing) and overestimate it after a crisis (there’s too much price volatility). Therefore, our models are systematically wrong in all states of the world (Danielsson 2019).

Regulation responds to the exogenous changes in the state of the world. But exogenous events that create systemic risk in recent history – the sub-prime crisis or Brexit, for example – are largely political. An unelected macroprudential regulator has limited legitimacy or ability to act to reduce that risk (Danielsson and Macrae 2016).

The instinct for self-preservation among market participants may also create endogenous volatility that drives crisis dynamics. In the quest to recognise and mitigate reported risks, one-size-fits-all regulation such as capital requirements and leverage constraints that governs short-term behaviour of participants in response to events and policy. Each actor attempts to reconcile regulation with their objectives (or biases), but they also interact in ways that may amplify the original signal.

Solving the control problem

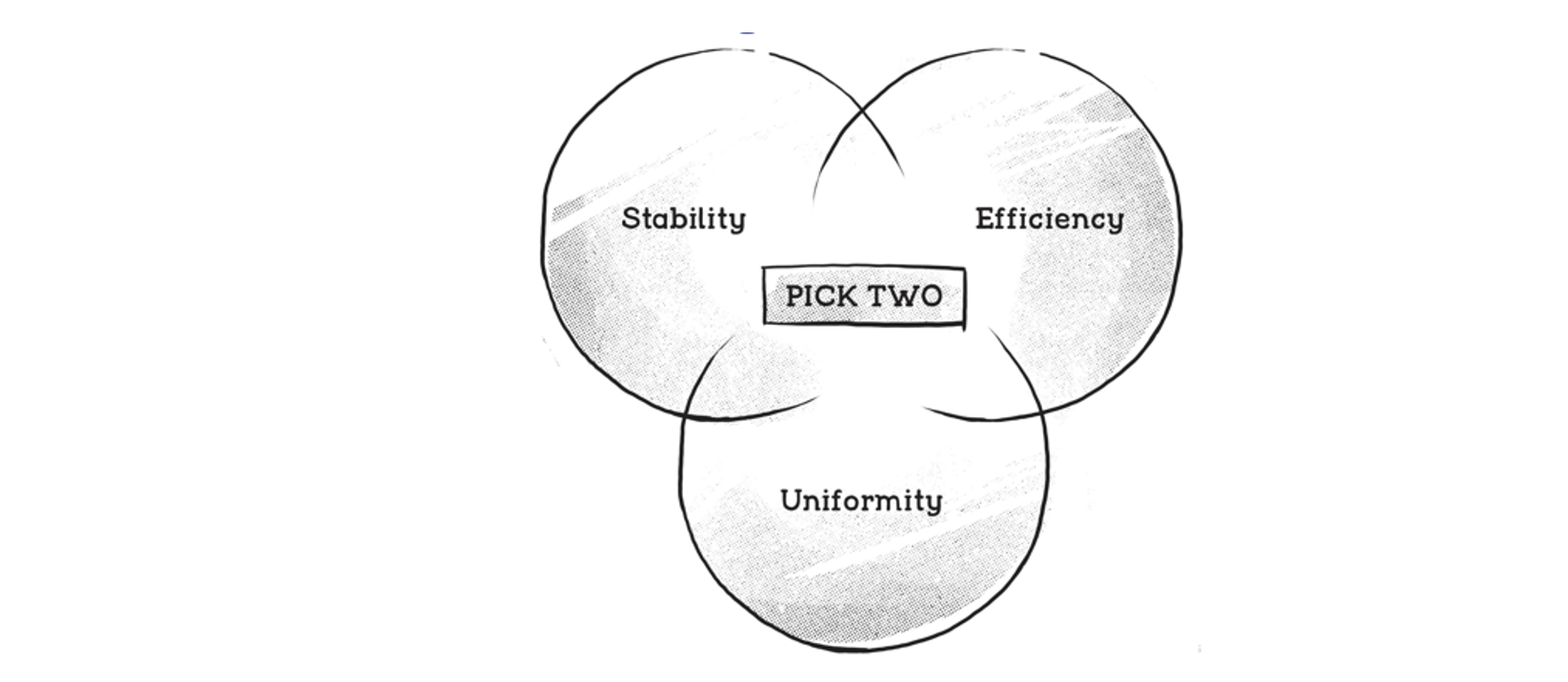

Therefore, there is a trilemma in regulation (Figure 4). We cannot have all of stability, efficiency, and uniformity.

Figure 4 The regulation trilemma

Source: Author.

Most regulators, certainly since 2008, have tended to choose uniformity. Uniform regulation aims for a level playing field. It focuses on measurable factors, driven by exogenous events. Therefore, regulated entities will tend to respond in similar ways to those events. It also addresses only a small part of the action space because it ignores endogenous changes – the risk-amplifying reactions of market participants.

Now imagine that we choose less uniformity in regulation and create more heterogenous financial institutions that are free to choose different responses to these events. This would help to increase the shock absorption capacity of the system, therefore improving automatic stabilisation. To do this, regulation would have to abandon the idea of the level playing field, reducing regulation on new entrants with new business models in areas like FinTech and DeFi.

This may be a hard sell to the risk-averse designers of regulation. It is also likely to be unpopular with the incumbents who would prefer existing regulation – not least because the high fixed costs of being part of that regime protect them from entrants. The alternative is to continue to create regulation that is not fit for purpose.

References

Carney, M (2017), “Ten Years On: Fixing the Fault Lines of the Global Financial Crisis”, Banque de France Financial Stability Review 21.

Danielsson, J (2009), “The myth of the riskometer”, VoxEU.org, 5 Jan

Danielsson, J (2019), “Perceived and actual risk”, VoxEU.org, 12 December.

Danielsson, J (2022), The Illusion of Control, Yale University Press.

Danielsson, J and R Macrae (2016), “The fatal flaw in macropru: It ignores political risk”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Danielsson, J and H S Shin (2002), “Endogenous Risk”, chapter in Modern Risk Management: A History.

Danielsson, J, H S Shin and J-P Zigrand (2009), “Modelling financial turmoil through endogenous risk”, VoxEU.org, 11 March.

Danielsson, J, M Valenzuela, and I Zer (2018), “Learning from history: Volatility and financial crises”, Review of Financial Studies 31(7).

Danielsson, Jon, Robert Macrae, Dimitri Vayanos, and Jean-Pierre Zigrand (2020), “The Coronavirus Crisis Is No 2008,” VoxEU.org, 26 March.

Danielsson, J, M Valenzuela and I Zer (2022a), “How global risk perceptions affect economic growth", VoxEU.org, 13 January.

Danielsson, J, M Valenzuela, and I Zer (2022b), “The impact of risk cycles on business cycles: A Historical view”, International Finance Discussion Papers and forthcoming in Review of Financial Studies.

Minsky, H (1986), Stabilizing an Unstable Economy, Yale University Press.

Valencia, F and L Laeven (2012), “Systemic Banking Crises Database: An Update, IMF Working Paper 2012/163.