High-skilled immigrants contribute a substantial and growing share of US innovation and entrepreneurship, accounting for about a quarter of US patents and firm starts. While recent research has begun to quantify these broad contributions and to measure traits of the types of firms created (e.g. Brown et al. 2018), many important factors about the innovation and entrepreneurial processes used by immigrants as opposed to natives are less explored. The rise of collocation workspaces presents an ideal environment to study these interactions, as many innovative individuals and firms are gathered in close proximity to facilitate the flow of ideas and information.

Previous research documents the importance of networking within collocation clusters and the associated advantages for entrepreneurs in terms of innovation and discovery, securing financing and other resources, and increasing venture performance. Katz and Wagner (2014) explain how network considerations are a large part of why such start-up company collocations are successful. Other studies focus on the importance of ethnic clustering; Saxenian (2000) describes how Chinese and Indian immigrant networks in Silicon Valley promoted the extensive clustering of Chinese and Indian high-tech entrepreneurs in this small geographic area. Despite the large share of immigrant-owned businesses (e.g. Kerr and Kerr 2017, 2018), immigrant entrepreneurs in the US tend to have a smaller network to draw upon when seeking financing, mentors, partners, employees, or clients than do typical native-born entrepreneurs (Raijman and Tienda 2000).

A survey of immigrant and native entrepreneurs

In a new paper (Kerr and Kerr 2019), we provide a rare economics-based view into how immigrant entrepreneurs network and how their networking behaviour differs from natives. Our study further compares immigrant entrepreneurs to natives working in the same facility, which is a new empirical approach in this research space. Finally, we complement earlier analyses on the ability of immigrant entrepreneurs to network by providing evidence linking networking behaviour to personality traits and other individual and firm characteristics.

The survey we developed focuses on individuals working at CIC, formerly known as the Cambridge Innovation Center, in three locations in the Boston area as well as CIC’s first expansion facility in St. Louis. The survey included extensive questions regarding the background of individuals (i.e. education and place of birth), the traits of their firms, their networking attitudes and behaviours both within and outside of CIC, their expectations for their company’s future, and their personality traits.

Survey responses show that immigrants value the networking capabilities at CIC more than natives. In our first inquiry, we group a set of questions around the respondent’s self-reported perceptions of CIC networking benefits. Respondents were asked to rate aspects of CIC in terms of their importance for the decision to locate the company there, and how it actually helped their business. Additional questions were used to gauge:

- the purposefulness of an individual’s networking;

- how CIC helped them access companies (a) at CIC, (b) within the vicinity of CIC, or (c) in the greater Boston/St. Louis area; and

- any perceived premium in CIC value-added compared to costs and over other competitors’ offerings.

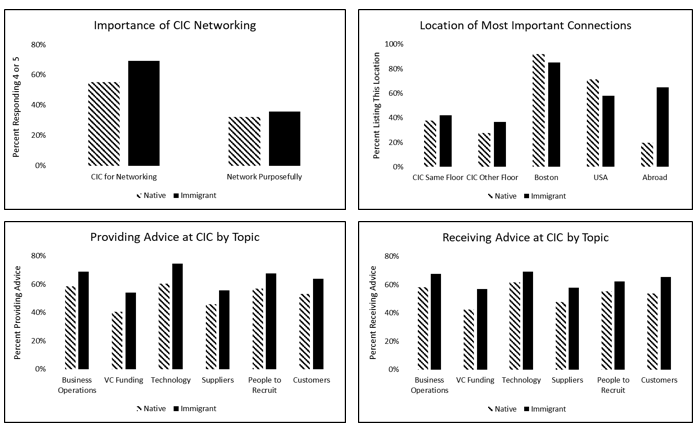

Figure 1 shows that in all cases, the raw average for the immigrant respondents exceeds that of the natives. Immigrants are more likely to consider networking opportunities an important factor in choosing to locate at CIC and to report having benefited from CIC in this regard.

Figure 1 Networking importance, location, and advice

The largest differences are found in the degree to which immigrants give advice to, and receive advice from, people within CIC who work outside of their company. For both of these actions, immigrants report substantially greater rates of information exchange than natives for six surveyed factors: business operations, venture financing, technology, suppliers, people to recruit, and customers. On providing advice, the immigrant differential to natives is highest on business operations and customers and lowest on venture financing. On receiving advice, the differential is highest on venture financing and customers, and lowest on suppliers and technology.

Next, a set of questions provide information on the types of networks possessed by individuals. Respondents were asked to estimate the number of persons at CIC (outside of the employees/investors of their own company) that they know well enough to believe that:

- these persons could be of benefit to their business over the next six months; or

- they would remember the respondent’s name in six months if they left CIC today

Immigrants report knowing more of both types of individuals at CIC, especially those who are likely to be beneficial to their business (4.9 versus 4.5). Furthermore, networks developed at CIC by immigrants tend to be one person larger than those of natives, on average, although these differences are usually not statistically significant. When asked to list the location of their five most important contacts, immigrant and native entrepreneurs at CIC display mostly similar reliance on CIC itself. For contacts outside of CIC, immigrant entrepreneurs are substantially more likely to list overseas locations, while native entrepreneurs are over-represented in terms of contacts elsewhere in the US.

Our final analyses consider the specific traits of the floors of the CIC building on which the company offices of immigrants and natives are located, to see if they interact differently with floor-level environments. The floors within each CIC facility can have a very different purpose – for example, one floor may be more populated with larger, fixed office spaces suitable for established teams, while another floor is a co-working space designed for very small and frequently changing teams or individual entrepreneurs. Conditional to the match of a client’s needs to a type of space, the specific floor and office allocation is otherwise based upon availability and often has a degree of randomness.

In our analysis, we measure six traits of each floor: inventor percentage, immigrant percentage, average age, female percentage, average firm size, and total number of firms. Across several specification designs, we do not find evidence that floor traits matter for the strength of the immigrant native differential with respect to networking. There is some evidence that the greater degree to which immigrants give and receive advice is accentuated on floors that have a high fraction of inventors, but the more important finding is that these floor-level shaping factors are second order to the main effects.

Concluding remarks

Networking and the giving and receiving of advice are crucial to entrepreneurship and innovation. Our analysis of CIC finds that immigrants take more advantage of networking opportunities at CIC, especially around the exchange of advice. This effect is quite robust, holding in the raw data and tightly controlled specifications, and it does not appear to be substantially mediated by floor-level traits. We are not able to assess whether this generates long-term performance advantages for immigrants, but it at least leads them to value CIC more than natives do.

Looking forward, we hope other researchers continue to examine differences in behaviours of immigrants within entrepreneurship and innovation compared to natives. It is now well established that immigrants make up a large and growing component of the US science and engineering workforce (Kerr 2018), and they have comparable overall quality on many dimensions to natives engaged in the field. But there remains much to be explored about how their preferences and interactions shape the communities of which they are becoming an ever-larger share.

References

Brown, J D, J S Earle, M J Kim, and K-M Lee (2018), “Immigrant entrepreneurs, job creation, and innovation”, Census Bureau Working Paper, Washington, DC.

Kerr, S P and W R Kerr. (2017), “Immigrant entrepreneurship”, in J Haltiwanger, E Hurst, J Miranda and A Schoar (eds), Measuring Entrepreneurial Businesses: Current Knowledge and Challenges, National Bureau of Economics, pp. 187-249.

Kerr, S P and W R Kerr (2018), “Immigrant entrepreneurship in America: Evidence from the survey of business owners 2007 & 2012”, NBER Working Paper No. 24494.

Kerr, S P and W R Kerr (2019), “Immigrant networking and collaboration: Survey evidence from CIC”, NBER Working Paper No. 25509.

Kerr, W R (2018), The Gift of Global Talent: How Migration Shapes Business, Economy & Society, Stanford University Press.

Katz, B and J Wagner. (2014), The rise of innovation districts: A new geography of innovation in America, Metropolitan Policy Program, Brookings Institute.

Saxenian, A (2000), Silicon Valley’s new immigrant entrepreneurs, Public Policy Institute of California.

Raijman, R and M Tienda. (2000), “Immigrant pathways to business ownership: A comparative ethnic perspective”, International Migration Review 34: 682-706.