In response to the Covid-19 outbreak in the spring of 2020, governments across the world approved lockdowns of different intensity to control the spread of the pandemic, alongside other pharmaceutical interventions (PIs) and non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs). After the intense and critical months of the emergency, governments then lifted the most restrictive measures, hoping that the use of masks, social distancing, and remote working could keep the pandemic at bay. However, in the last few weeks, the fear of a second wave started to grow as the number of new infections is on the rise in most countries. Some countries, such as Israel, have already instituted a new lockdown; others, especially in Europe, are discussing the adoption of more severe measures on mobility and economic and social activity. Since the spring, we have learnt several facts about the spread of the virus – for example, that the use of masks is fundamental (Lyu and Wehby 2020) – that changed the discussion about a second lockdown. Yet, we do not know much about the effectiveness of the initial severe lockdowns during the peak of the first wave of the epidemic.

The Italian economic lockdown

In recent research, we address this question (Borri et al. 2020). We study the Italian case in order to estimate by how much the intensity of a lockdown reduced the number of deaths by Covid-19. The focus on Italy – one of the first countries struck by Covid-19 – is motivated by the design of the lockdown implemented by the government, which offers a source of plausibly exogenous variation in its intensity at a granular level. In response to the Covid-19 outbreak, the Italian government imposed the closing of all schools on 5 March and a first lockdown on 11 March, which shut down many business activities open to the public including restaurants and gyms. It then imposed a second, economic lockdown on 22 March. For this second lockdown, the government defined a list of essential economic activities that were allowed to continue operating, while all others were either suspended or allowed to operate only remotely. These policy provisions induced a geographically heterogeneous variation in the share of active workers across municipalities, which is pre-determined by economic activity in a given municipality and independent of the pandemic. We match the list of essential economic activities with data on the number of workers in such essential jobs at the municipal-NACE 3-digit level. Important to our analysis, we cover a granular sample of 7,089 municipalities, with a median population of 2,443 residents and a median area of 21 square kilometres, each belonging to one of the 110 Italian provinces.

Impact on mobility

To gauge the effect of the lockdown, we split the sample of Italian municipalities into two groups. For each Italian province, we calculate the median of the reduction in the share of the active population after the economic lockdown on 22 March 22, and then we group together municipalities below and above their provincial median. Municipalities above the median experienced on average a 42.5 percentage point reduction in the share of the active population, while those below the median experienced only an average 17 percentage point decrease. Similar to Glaeser et al. (2020), we first estimate the reduction in mobility induced by the economic lockdown by comparing municipalities above and below the median, before and after 22 March.

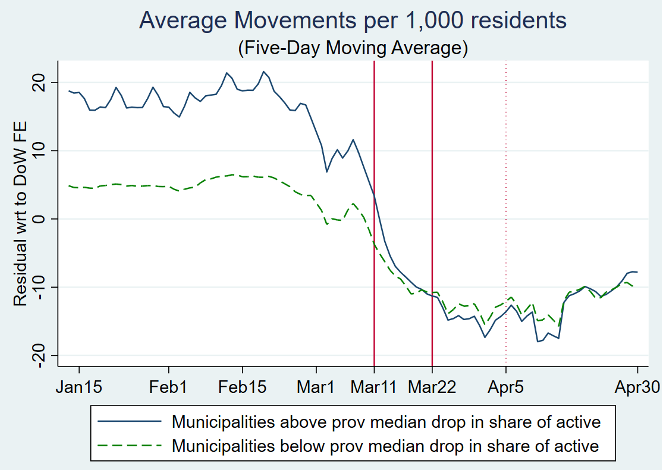

In Figure 1, we report the mobility patterns for the two groups of municipalities. We observe that the decline in mobility occurred well before the first and the second lockdown for all municipalities. However, the second lockdown on 22 March caused an additional drop in mobility in municipalities where the reduction in the share of active workers is above the provincial median. Specifically, we estimate that municipalities with a larger contraction in the share of active workers experienced a reduction in daily mobility of around 53 kilometres per 1,000 residents with respect to municipalities with a smaller contraction in the share of active workers.

Figure 1 Evolution of the 5-day moving average in the kilometres per 1,000 residents (as residuals with respect to day-of-the-week fixed effects)

Inactive workers and mortality due to Covid-19

We proxy mortality due to Covid-19 by excess deaths at the municipal-day level – measured as the difference between the daily number of deaths in 2020 and the average number of deaths on the same day and in the same municipality between 2015 and 2019. This overcomes, at least partially, issues related to differences in the classifications of deaths due to Covid-19, testing, and hospital capacity (Buonanno et al. 2020, Galeotti and Surico 2020). To capture the consequences of the second lockdown on excess deaths, we follow the medical literature and adopt a conservative approach by imposing that the potential effects on deaths manifest with a two-week lag from the contagion (Wilson et al. 2020, Sun et al. 2020).

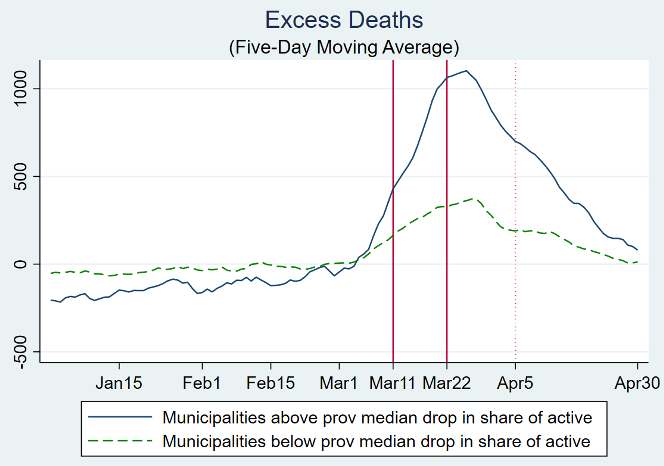

In Figure 2, we plot the evolution in the five-day moving average of excess deaths for the two groups of municipalities. The figure shows that, despite the closing of schools and the other containment measures of the first lockdown, both groups of municipalities experienced a rise in excess death at the beginning of March which lasted until the end of the month. Importantly, above-median municipalities experienced a sharper increase in excess deaths in the first lockdown period (11-22 March) while they experienced a sharper decrease in the second lockdown period (22 March-30 April) compared with below-median ones. In line with a mechanism linking active workers and mortality by Covid-19, this suggests that municipalities characterised by a higher share of active workers and consequently mobility paid a higher death toll before the economic lockdown, while they experienced a more marked reduction of mortality by Covid-19 once the lockdown was in place.

At the same time, Figure 2 does not seem to support the standard parallel trend assumption – the requirement that in the absence of treatment, the difference between the treatment and control groups is constant over time – which is necessary for a difference-in-difference design. For this reason, we address potential violations of this assumption by controlling for the dynamics of excess deaths, by estimating bounds for our estimates (Angrist and Pischke 2008) and by showing that our results are robust to our choice of sampling municipalities with more similar or almost identical pre-trends, as for example municipalities with fewer than 5,000 residents.

Figure 2 Excess deaths in 2020 versus 2015-2019

Our key finding suggests that the intensity of the economic lockdown is associated with a statistically significant reduction in mortality by Covid-19, in particular for the age groups of 40-64 and older, with larger and more significant effects for individuals over 50. Back-of-the-envelope calculations indicate that in the 26 days between 5 April and 30 April, a total of 4,793 deaths were avoided in the 3,518 municipalities which experienced a more intense lockdown. The results are robust to the inclusion of provincial time varying shocks and alternative specifications such as looking at a linear model (i.e. considering a linear drop in the share of active population on excess deaths) and weighting the share of active workers on proximity and work-from-home indexes, among others.

Alternative mechanisms

Interestingly, we do not find significant effects of the lockdown in the south of Italy. Although this result is not surprising because the effects of the epidemic were modest in this part of the country, it is at the same time a useful placebo exercise that excludes other confounding mechanisms. For example, our findings might be contaminated by the fact that in municipalities with a larger drop in the active population there were also less deadly car or workplace accidents. However, the fact that we do not find a significant effect in the south, where the diffusion of the pandemic was negligible, would indicate that the effect of these alternative channels is, if anything, small. In our paper we discuss other possible confounding mechanisms that may explain our results, such as reversion-to-the-mean or the effect of the first Italian lockdown. We argue that the available evidence does not support these alternative mechanisms. While we cannot precisely identify the channel through which the lockdown might have reduced the contagion, the main candidate is the reduction in mobility of active workers that was induced by the lockdown.

Conclusions

Our results are a first step to evaluate the costs and the benefits of a severe lockdown and may be helpful to guide policymakers in their decisions regarding a safe relaxation of these measures after the current medical emergency, and to evaluate which policies are more effective to contain future pandemics. Clearly, we cannot claim the same effects would necessarily hold in different settings – for example, when more masks are available (Lyu and Wehby 2020) or a better contact tracing system is in place. More generally, our empirical strategy provides a simple methodology for future research aiming at assessing the impact of the economic lockdown in reducing Covid-19 deaths in other countries.

References

Angrist, J D and J S Pischke (2008), Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Borri, N, F Drago, C Santantonio and F Sobbrio (2020), “The “Great Lockdown”: Inactive workers and mortality by Covid-19”, CEPR Discussion Paper 15317.

Buonanno, P, S Galletta and M Puca (2020), “Estimating the severity of Covid-19: evidence from the Italian epicenter”, Plos One (forthcoming).

Galeotti, A and P Surico (2020), “A user guide to Covid-19”, VOX.org, 27 March. https://voxeu.org/article/user-guide-covid-19

Glaeser, E L, C S Gorback and S J Redding (2020), “How much does Covid-19 increase with mobility? Evidence from New York and four other U.S. cities”, NBER Working Paper 8345.

Lyu, W and G L Wehby (2020), “Community use of face masks and Covid-19: Evidence from a natural experiment of state mandates in the U.S.”, Health Affairs 39 (8).

Sun, P, X Lu, C Xu,W Sun and B Pan (2020), “Understanding of Covid-19 based on current evidence”, Journal of Medical Virology 92 (6).

Wilson, N, A Kvalsvig, L T Barnard and M G Baker (2020), “Case-fatality risk estimates for Covid-19 calculated by using a lag time for fatality”, Emerging Infectious Diseases 26 (6).