We know from the seminal contribution of Gabaix (2011) that changes in the performance of some very large firms matter for aggregate outcomes in granular economies. The ‘micro to macro’ approach, linking micro behaviour to macro outcomes, has considerably advanced our understanding of macro aggregates such as business cycles, comparative advantage (Gaubert and Itskhoki 2020), and the international transmission of shocks (Di Giovanni et al. 2012).

Since changes in the performance of these large firms matter for the macroeconomy, it is paramount to understand their roots. Why do large firms perform differently than smaller ones? While the literature has focused on the role of idiosyncratic shocks (Kramarz et al. 2019), a complementary view poses that large firms have differential reactions to common shocks affecting all firms. This approach posits that macro shocks lead to heterogeneous reactions, in particular by the largest firms, which in turn determine the macro reaction to the initial shock – i.e. from macro to micro to macro. In a recent paper (Bricongne et al. 2022), we analyse the contribution of the largest exporters to aggregate export fluctuations over a long period, spanning 1993 to 2020. We rely on the universe of detailed firm-level export data collected by the French Customs office, containing export values by the destination country at finely defined product codes and, crucially, available at a monthly frequency.

In Figure 1, we decompose aggregate export growth (at the quarterly frequency for the sake of readability) into an unweighted average of firm export growth rate and a granular residual. The latter captures the covariance between firm size and firm growth. If the response to macro shocks were uncorrelated with firm size, then the granular residual would be zero. The granular residual is not zero, and, furthermore, it explains a large share of aggregate export fluctuations: 42% of the variance of aggregate export growth. Moreover, the correlation coefficient between unweighted average firm growth and the granular residual is close to 0.5. This implies that large exporters tend to do worse than the average firm in times of downturn and better than average in times of upturn.

Figure 1 Average firm export growth and the granular residual

Note: The mid-point growth rate of aggregate quarterly French exports is decomposed into the unweighted average growth rate across continuing exporters (blue line) and the covariance between exporter size and the unweighted growth rate (the granular residual, red line).

Large exporters drove the export collapses in the Global Crisis and the pandemic

The overreaction of large firms to macro shocks is sizeable and clearly seen in the case of the two largest macro global shocks of the past decades, in which the collapses of French exports were of similar magnitude (-17.4% for 2009/2008 and -16.3% for 2020/2019). Not only are the two export collapses almost entirely explained by the intensive margin (firms that continue to export), but they were also caused by the largest exporters, whose export growth rates were significantly lower than those of the average exporter.

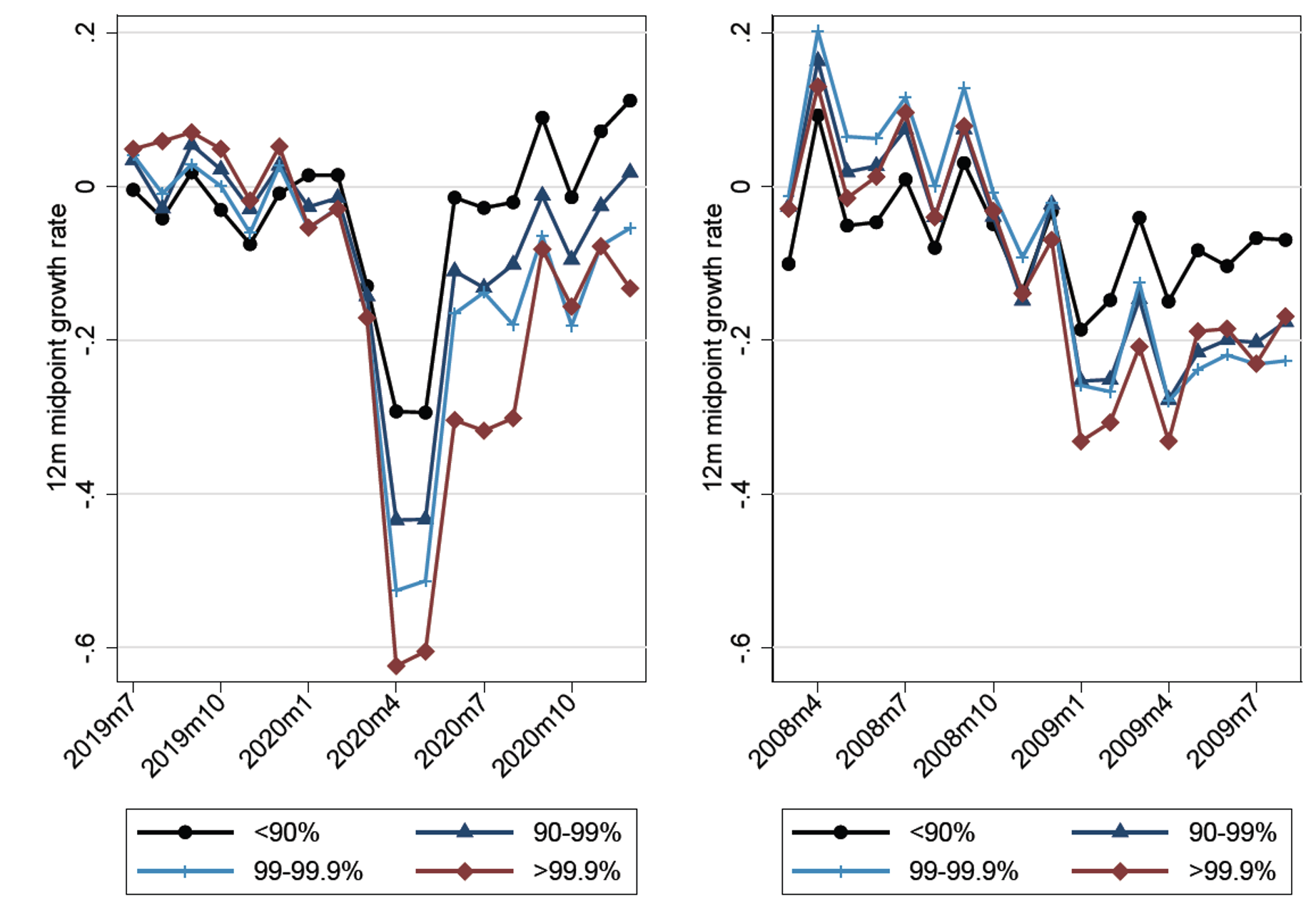

We illustrate this in Figure 2, where we plot weighted average year-on-year mid-point growth rates by non-overlapping size bins of exporters. Size bins are defined using the pre-crisis exporter size distribution (2019 for Covid and 2008 for the Global Crisis). Growth rates were cleaned of composition effects in terms of the sectoral and geographical profiles of firm-level exports and thus calculated as the growth of exports within finely defined markets. The top 0.1% exporters (roughly 100 firms out of 100,000) are represented by the red line.

The message is clear-cut: growth of the top exporters declined substantially more than the average exporter, controlling for composition effects in terms of sectors and destinations. This pattern holds in both crises. Interestingly, in both events, the largest exporters also experienced a slower recovery than those in the bottom 90%.

Figure 2 Growth rates of exports during the Covid crisis (left) and Global Crisis (right), by size bin

Note: 12-month weighted average mid-point growth rates by decile of the exporter size distribution. Exporter size bins are defined using the pre-crisis distribution export size distribution (total firm-level exports in 2019 in the case of Covid and total firm-level exports in 2008 for the Global Crisis).

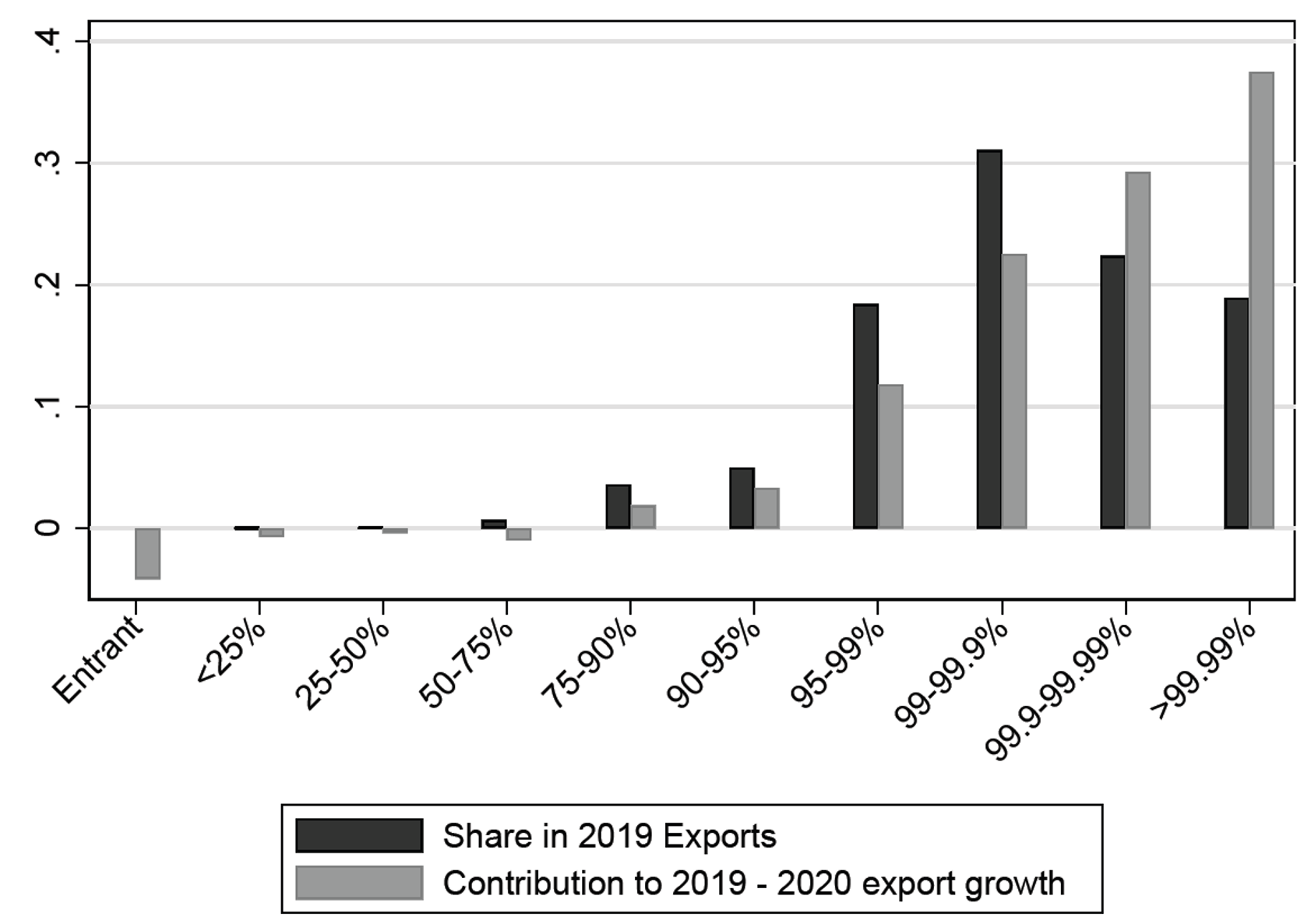

We zoom in on the export collapse of April and May 2020 in Figure 3. Given the large concentration of exports, we choose particularly fine bins at the top of the distribution. For instance, the top 1% (roughly 1,000 firms) account for over 70% of total exports. The black bars show the share of aggregate exports in April and May 2019 accounted for by each size bin.

We then compare the pre-crisis export share of each bin with its contribution to the aggregate export collapse between April and May 2019 and April and May 2020, measured as the change in total exports of a bin divided by the change in aggregate exports. If all firms grew at the same rate, the contribution of each bin would equal its pre-crisis share. The figure shows that the small group of ‘superstar’ exporters disproportionately explain the slump in exports. The top 0.1% of exporters contributed 57% to the collapse in aggregate exports, while their pre-crisis share was only 41%. Within the top 0.1%, the ten largest exporters alone account for around one-third of the export collapse, while they exported 19% of the total pre-crisis values. The message is the same as in Figure 1. The negative relationship between pre-crisis size and export adjustment to the crisis also holds within the set of 1,000 larger exporters.

Figure 3 Export share in 2019 Covid and contribution to 2019-2020 trade growth, by size bin

Note: Pre-crisis export share and contribution to the aggregate export collapse between April and May 2019 and April and May 2020. Exporter-size bins are constructed using the 2019 export value by firms.

The 2020 collapse of French exports was driven by demand shocks; global value chain disruptions played a lesser role

The Covid-19 pandemic provides us with an excellent laboratory to study the role of heterogeneous reactions to aggregate shocks. The shock was sudden and exogenous. While sanitary measures were imposed in most French trade partners, their timing offer variation that we can exploit, thanks to the monthly frequency data, to measure both supply and demand shocks.

Large firms are indeed more likely to be more engaged in complex global value chains (GVCs) (Antras 2020) and more likely exposed to supply disruptions caused by systemic shocks (Baldwin and Freeman 2022). Our aim is to understand whether the larger GVC exposure of top exporters can explain their stronger reaction to the shock, not whether GVCs are important per se. We complement the export data with information on firm-level imports and sales and measure the GVC exposure of each exporter with the ratio of imported intermediate inputs to sales (IIS ratio) and supply shock exposure using the information on lockdowns in the origin countries of imports. We develop a flexible regression framework that relates growth rates in each market (defined as a product-destination pair) to size bin dummies. The data reveal that adding GVC measures to our regressions does not affect the magnitude and significance of the exporter size-bin dummies. In other words, the overreactions of large exporters were not due to their deep engagement in GVCs.

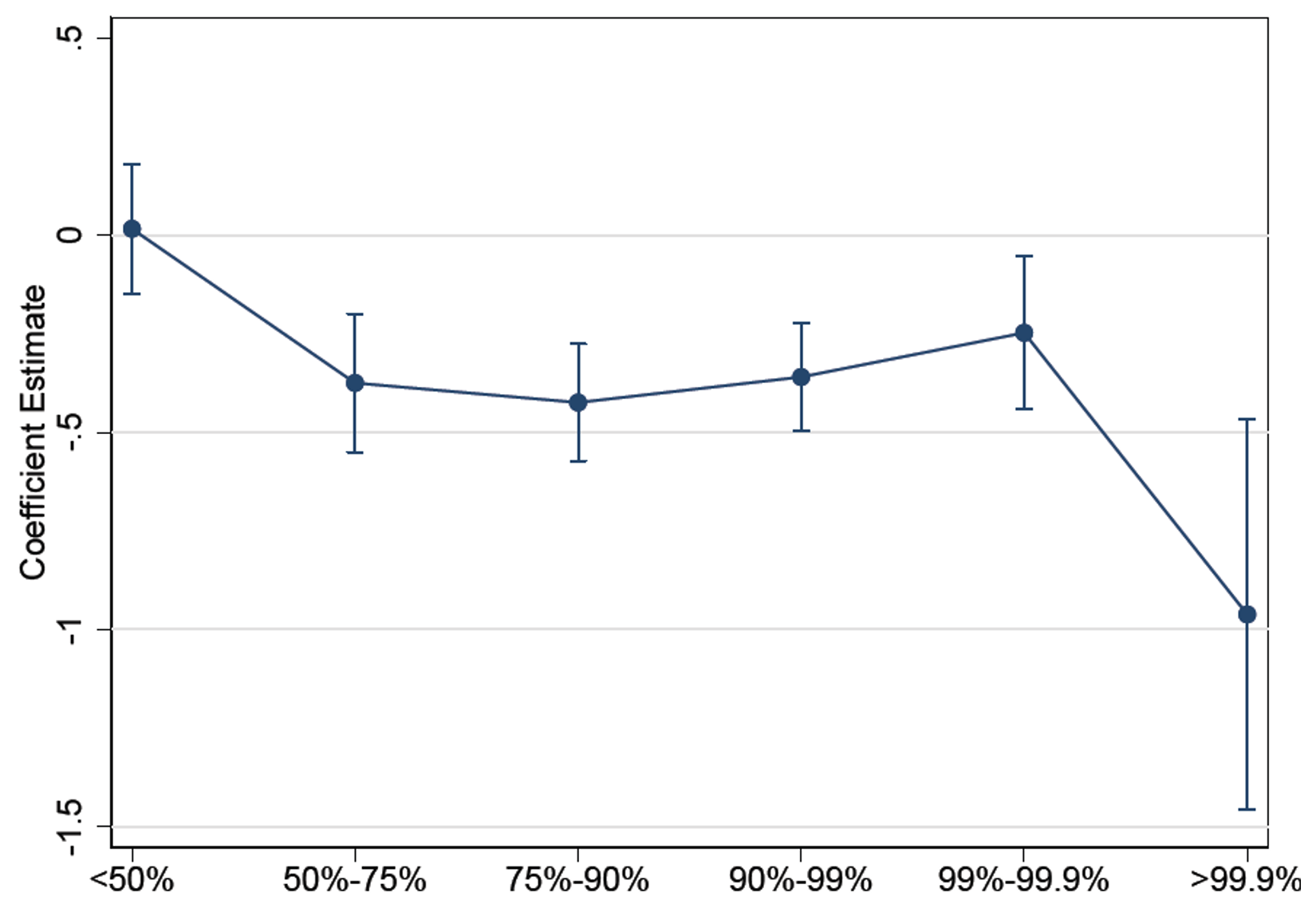

In contrast, we do find convincing evidence of a demand channel which is not driven by the sector or destination composition of exporters. Instead, we estimate a larger elasticity of large firms to destination-country lockdowns. In particular, we regress the midpoint growth rate at the firm-product-country-month level on the Oxford Stringency Index (Hale et al. 2021) in each origin country each month. Identification exploits variation in export growth of the same firm across destinations with varying degrees of lockdowns, fully controlling for product-level shocks. The regression fully controls for firm-level supply shocks, originating both in France and abroad, by including firm*month fixed effects. The results are shown in Figure 4. On average, going from full to no lockdown reduced the midpoint growth rates by 0.6 points. However, the effect is strongly heterogeneous, being almost double for firms in the top 0.1% with (1.0) with respect to the bottom 99.99% (below 0.5).

Figure 4 Effect of destination lockdown by size bin

Note: Lockdown stringency is interacted with a set of six complementary size dummies, in a regression including firm-month, product-month, and destination fixed effects. The dependent variable is the mid-point growth rate of exports by firm, product and destination country during a given month. We plot point estimates and 1% confidence intervals.

Identifying the role of large firms for macroeconomic aggregates is a lively and critically important area of research. It has a variety of implications for the framing of economic policies (see, for example, an application to imports of Russian fuel, Lafrogne-Joussier et al. 2022). Our results show that the response of aggregate exports to large macroeconomic shocks is largely driven by the large weight of large firms in the economy and their greater sensitivity to these shocks. The very high contribution of export champions to commercial success may thus turn into a vulnerability in the event of a sudden downturn in the business cycle.

References

Antras, P (2020), “Conceptual aspects of global value chains”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 9114.

Baldwin, R and R Freeman (2022), “Global supply chain risk and resilience”, VoxEU.org, 6 April.

Bricongne J C, J Carluccio, L Fontagné, G Gaulier and S Stumpner (2022), “From Macro to Micro: Large Exporters Coping with Common Shocks”, Bank of France Working Paper 881.

Di Giovanni, J, A Levchenko and I Méjean (2012), “The role of firms in aggregate fluctuations”, VoxEU.org, 16 November.

Di Giovanni, J, A Levchenko and I Méjean, (2020), “Foreign shocks as granular fluctuations”, Bureau of Economic Research Working Paper 28123.

Gabaix, X (2011), “The granular origins of aggregate fluctuations”, Econometrica 79(3): 733-772.

Gaubert C and O Itskhoki (2020), “Superstar firms and the comparative advantage of countries”, VoxEU.org, 14 August.

Hale, T, N Angrist, R Goldszmidt, B Kira, A Petherick, T Phillips, S Webster, E Cameron-Blake, L Hallas, S Majumdar and H Tatlow (2021), “A global panel database of pandemic policies (Oxford COVID-19 government response tracker)”, Nature Human Behaviour 5: 529–538.

Kramarz, F, J Martin and I Méjean (2019), “Idiosyncratic risks and the volatility of trade”, VoxEU.org, 11 December.

Lafrogne-Joussier, R, A Levchenko, J Martin and I Méjean (2022), “Beyond macro: Firm-level effects of cutting off Russian energy”, VoxEU.org, 24 April.