The important and exciting developments in the antitrust of digital markets may have somehow distracted attention from potential problems in the more mature and less exciting – but still important – fields like cartel enforcement. In most countries, the number of cartels investigated and of applications to programmes offering leniency to cartel members that self-report and collaborate with competition authorities have fallen significantly in the last decades (OECD 2022). The fall has been particularly stark for the European Commission (EC) (e.g. Ysewyn and Kahmann 2018) and was extreme in the last decade (see below). This may be seen as good news, if we take the optimistic view that the fall is caused by a corresponding fall in the number of cartels formed, possibly due to an increase in the deterrence effects of public and private antitrust enforcement. Or it can be seen as bad news, if we take a more pessimistic stance and believe the fall may be due to a reduction in the ability of the antitrust authorities, and in particular of the EC, to detect and investigate cartels given the lack of resources and the increased focus on digital markets.

At the same time, two other trends emerged at the European level. First, antitrust damage actions in the EU have increased significantly (e.g. Norton Rose Fulbright 2023). Numerous cartel members, including leniency applicants who obtained immunity from fines, have found themselves confronted with substantial damage claims. A notable example is MAN Truck & Bus SE, the reporting firm in the trucks’ cartel fined by the EC in 2016, which was recently mandated to pay €24.3 million in Spain. MAN is (or was until recently) also actively fighting damage claims in several other jurisdictions, including the Netherlands, Germany, Ireland, Portugal, and the UK. Second, the amount of leniency awarded to cartel members other than the first applicant has increased considerably, with several cases in which all cartel members received some leniency, even when the cartel’s existence was already known because it was previously discovered in the US (Marvão and Spagnolo 2023). This column discusses how the 2014 EU Damages Directive, which facilitates private actions by cartel victims, and the recent trend of ‘leniency inflation’ may have contributed to the dramatic decline in the number of cartels investigated by the EC in most recent years.

The downward trend in European Commission cartel cases

Since 2020, only six cartel investigations have been officially initiated.

Among these, two cases were closed with no fine, and three remain under investigation.

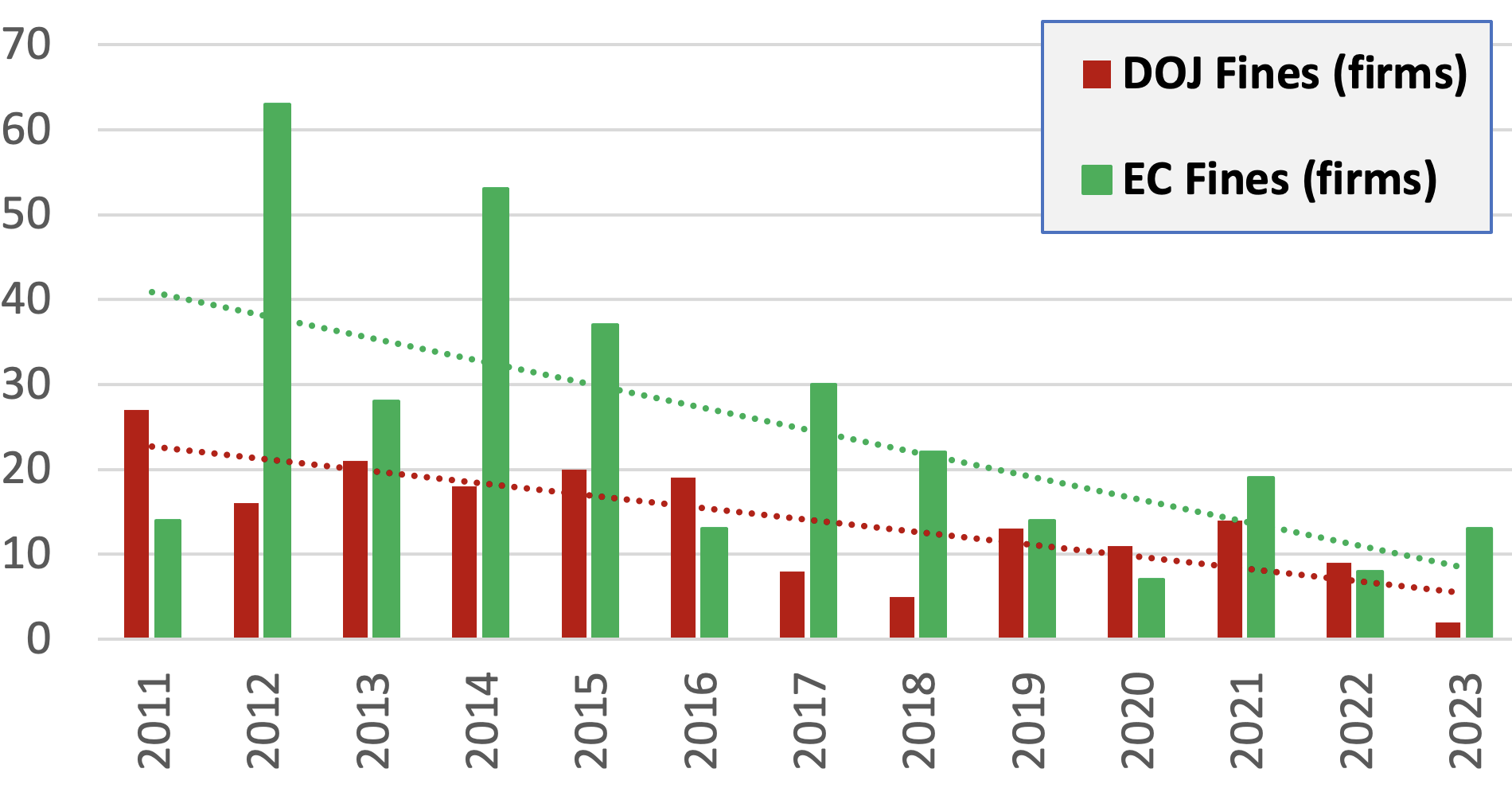

As a direct effect of the decrease in the number of investigations, the number of fines has decreased as well.

In 2023, only three fines were imposed, relating to hand grenades, the SNBB drug, and euro-denominated bonds, with one case still pending.

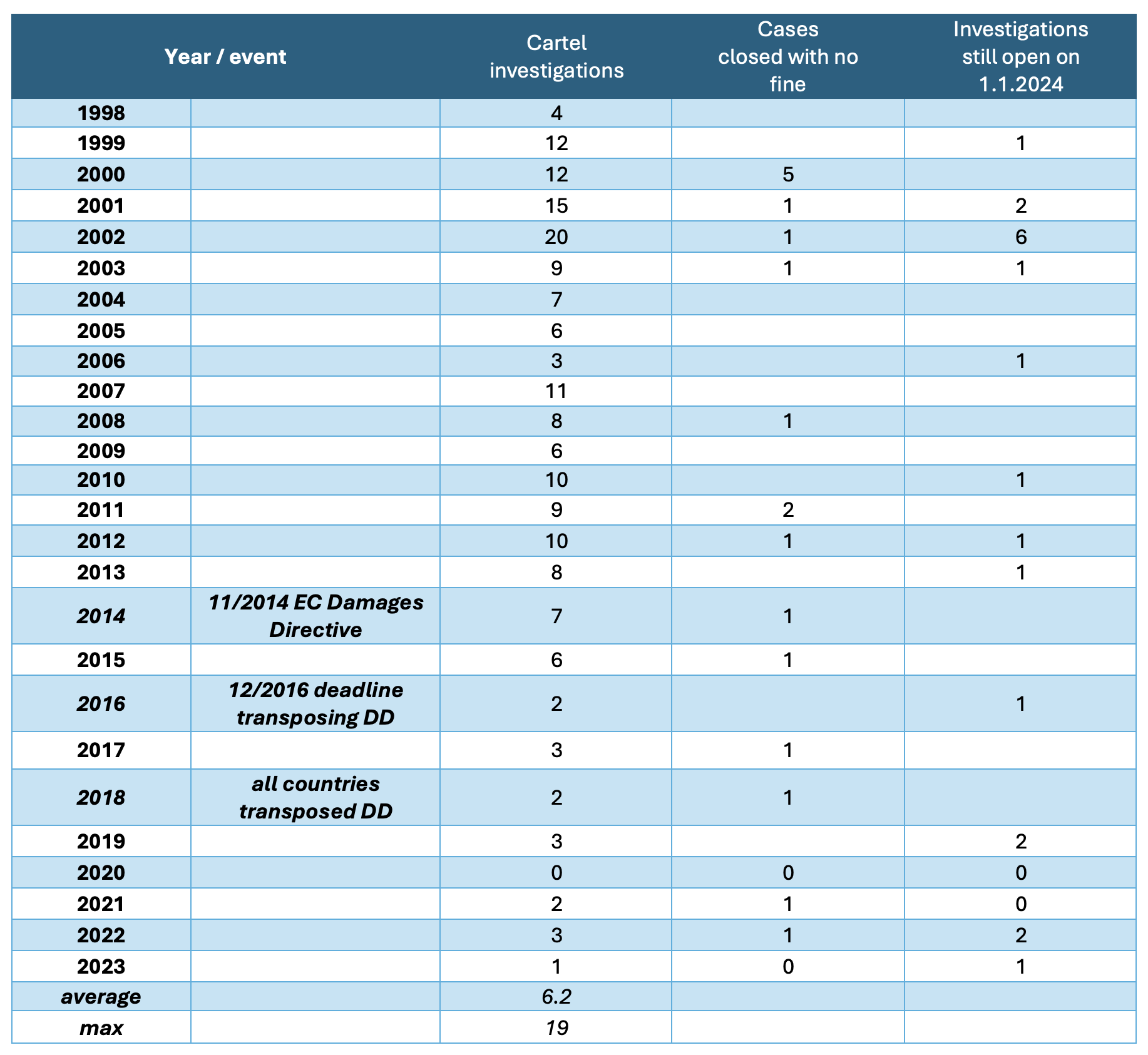

Table 1 describes the annual count of investigations conducted by the European Commission from 1998 to 2023.

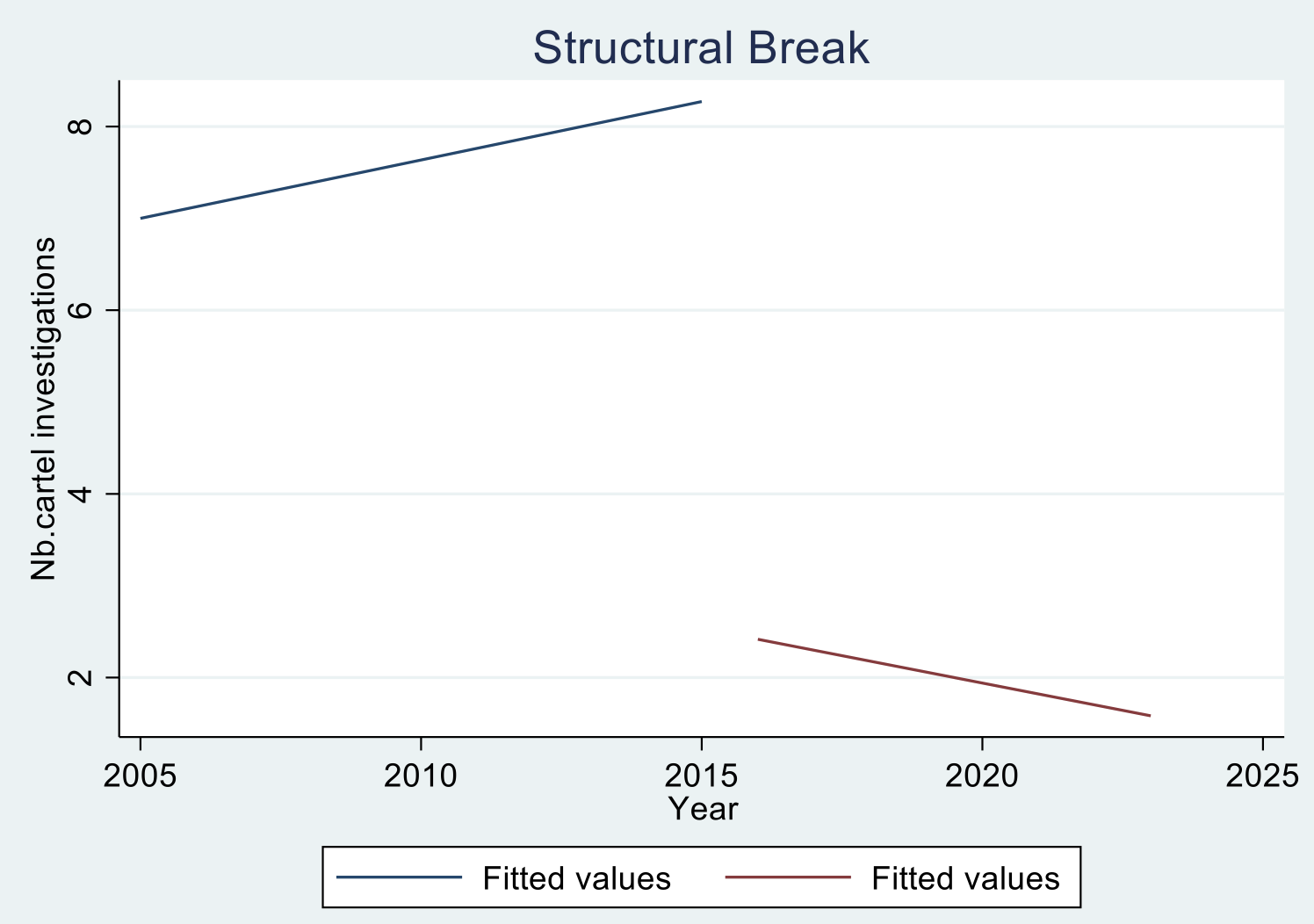

The annual tally of EC cartel investigations has had a downward trend for quite some years, but the fall became much steeper after 2015, as vividly illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1 Number of cartel investigations by the European Commission, 1998-2023

Source: European Commission website.

Figure 1 Number of investigations by the European Commission (start date), and two-period linear trend line, 2005-2023

Source: European Commission website.

The 2014 Damages Directive

The particularly stark fall in EC leniency applications, and consequently in cartel investigations, was anticipated by Buccirossi et al. (2015) as a likely outcome of the 2014 Damages Directive.

This is because the Directive facilitates damage claims in several ways but does not sufficiently protect the first leniency applicant (the immunity recipient) from becoming the first target of damage claims. The perspective of being targeted by damage claims from their customers (the protection by the Directive is limited to damages of other cartel members’ customers), immediately after self-reporting (the immunity recipient is the first convicted cartel member and the only one with no interest in appealing to delay the conviction), is likely to have had a significant chilling effect on the incentives to apply for leniency.

Curiously enough, not only does the Directive undermine the incentives to apply for leniency with the poor protection from damages it offers to leniency applicants, but it also makes damage claims more difficult by limiting claimants’ access to leniency statements. The legislator’s alleged aim was to strike a ‘compromise’ between the need to safeguard public enforcement (leniency programmes) and private enforcement (the victim’s right to sue for damages). However, it ended up damaging both. Buccirossi et al. (2020) formally show that such a compromise was never needed, as with sufficient protection of the immunity recipient from damage claims, leniency statements should optimally be made fully available to claimants. This is because sufficiently reducing (ideally removing altogether) the liability for damages of the first leniency applicant and shifting all liability for damages to other cartel members, ensures that leniency and damages become complements, reinforcing each other in deterring cartels. Facilitating damage claims while protecting the first leniency applicant from them strengthens firms’ incentive to ‘rush to the courthouse’ or apply for leniency first, increasing the riskiness of forming a cartel in the first place. The authors demonstrate that the effectiveness of antitrust enforcement is maximised by minimising the civil liability of the first leniency recipient and maximising the ability of cartel victims to sue for damages by affording claimants full access to all evidence gathered by the competition authority.

With the 2014 Directive, instead, firms reporting first and obtaining full immunity from fines by the EC continue to be hunted down by damage claims. Reporting firms such as INEOS (styrene EC cartel fined in 2022), Westlake (ethylene EC cartel fined in 2020), and MAN (trucks EC cartel case fined in 2022), all avoided cartel fines but are all currently fighting damage claims in various courts across the EU (and the UK).

Figure 2 Linear trend of the number of investigations by the European Commission in 2005-2023, fitted values around the structural break (2016)

For this column, we formally tested the hypothesis that the 2014 EU Damages Directive created a structural break in the falling pattern of EC cartel investigations.

The structural breakpoint in the data is estimated to take place in 2016. This means that the mean of the cartel investigations’ series is statistically lower post-2016, coinciding with the deadline for the transposition of the Directive, as depicted in Figure 2.

This sharp, non-constant decline in leniency programme applications appears to be unique to the EU.

‘Leniency inflation’ and the death of the ‘rush to the courthouse’

The fall in the attractiveness of leniency programmes may have been exacerbated by the recent EU phenomenon of ‘leniency inflation’, documented in Marvão and Spagnolo (2023). With this term, we indicate the consistent increase in both the number and magnitude of leniency reductions in fines granted to any given cartel. The possibility of securing substantial leniency – even when applying for leniency second, third, or last – is obviously poised to diminish the ‘rush to report first’, a cornerstone for the effectiveness of these programmes for society emphasised for decades as the essence of a good leniency policy by both (most) economists and US prosecutors. Within the EC cartel cases spanning the years 1998 to 2020, 58% of the cartel fines imposed included a leniency reduction. In certain years, this figure exceeded 90%. Given an average of five firms per cartel, this equates to approximately three members out of five obtaining leniency – even though many of these cartels were known to exist almost for sure because they were international in scope and had already been discovered and investigated in other jurisdictions (typically the US).

Moreover, there has been a discernible uptick in the proportion of cartel members that obtain leniency. Both the number of firms that receive full immunity and a leniency reduction are increasing. Recent instances such as those involving the EC automotive parts’ cartels, unveil a scenario where all cartel members obtained leniency! Finally, the magnitude of the average leniency reduction granted to each cartel member also exhibits an upward trajectory, escalating from approximately 23% in 1998 to nearly 60% in 2020. Why would a cartel member rush to disclose the cartel applying first for leniency, if it can always wait, keeping the cartel secret, with the option of receiving considerable leniency applying second, but only if some other cartel member chooses to reveal the cartel applying for leniency first?

Trends outside the EU

As mentioned, in the last decades there has been a generalised, worldwide deceleration in leniency applications and cartel investigation, though much milder and not concentrated in the post-directive period as for the EC.

This global deceleration of antitrust enforcement has not yet been convincingly explained and may be linked to several contributing factors. For example, the increased sophistication and prevalence of compliance programmes and internal monitoring may have both increased deterrence and decreased detection rates. The imposition of substantial fines across multiple jurisdictions may have further diminished the incentive to apply for leniency in any single jurisdiction (Ginsburg and Cheng 2020). Advancements in technology may have facilitated the substitution of unlawful collusion with lawful tacit collusion or enabled self-cancelling communication tools that do not leave traces that can be reported and brought to court. Finally, while Covid-19 may have reinforced the declining trend in antitrust enforcement, evidenced by fewer dawn raids in 2020 and 2021, it is worth noting that this downward trend started well before the onset of the pandemic. Future work should further investigate the reasons behind this global fall. Our focus here is to provide a likely explanation for the much more pronounced deceleration in the EU compared to other jurisdictions, such as the US (see Figure 2), in particularly in the last decade, after the introduction of the 2014 Damages Directive.

Figure 3 Number of firms fined in European Commission and Department of Justice cartel convictions, by fine date, 2011-2023

Conclusion

Abstracting from digital markets, cartel enforcement is the most important antitrust activity in terms of the effects on countries' increased productivity (Buccirossi et al. 2013). The aggregate negative effects of cartels are very large (Moreau and Panon 2023). The current, still too low level of EC fines compared to the US (Marvão and Spagnolo 2023), coupled with ‘leniency inflation’ - even for cartels already discovered in other jurisdictions - and with the insufficient protection of the immunity recipient under the 2014 Damages Directive, collectively seem to have contributed to a stark reduction in the number of leniency applications in the last decade. Given the reliance on leniency programmes for cartel investigation, this apparently translated into a similarly stark drop in the number of such investigations.

This suggests that we should strengthen EU cartel enforcement. The EC’s effort to decrease the almost exclusive reliance on leniency programmes is commendable. However, strengthening cartel enforcement absolutely requires: (i) amending the Damages Directive to protect much better (ideally, fully isolate) the first leniency applicant / immunity recipient from damage claims (at least until the rest of the firms are convicted) as shown to be optimal in Buccirossi et al. (2020), and already implemented in some European countries before the Directive forced them to change their law, (ii) stopping leniency inflation, that is likely to harm both deterrence and detection, although it may be making prosecutors’ life easier, and (iii) further increasing fines, as was suggested in the previous debate on criminalisation (the data do not suggest that the firm’s fine-to-turnover ratio increased in the past decade), or introducing criminalisation in the form of prison sentences, which might also strengthen the incentives to report.

References

Buccirossi, P, L Ciari, T Duso, G Spagnolo and C Vitale (2013), “Competition policy and productivity growth: An empirical assessment”, The Review of Economics and Statistics 95(4): 1324–1336.

Buccirossi, P, C Marvão and G Spagnolo (2015), “Leniency and damages”, CEPR Discussion Paper 10682.

Buccirossi, P, C Marvão and G Spagnolo (2020), “Leniency and damages”, The Journal of Legal Studies 49: 335–379.

Cauffman, C (2011), “The interaction of leniency programmes and actions for damages”, The Competition Law Review 7(2): 181–220.

European Commission (2022), “Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) on Leniency”, Version of October 2022.

Ginsburg, D and C Cheng (2020), “The Decline in U.S. Criminal Antitrust Cases: ACPERA and Leniency in an International Context”, George Mason Law & Economics Research Paper No. 19-31.

Jaspers, M (2023), “Keynote Speech by DG-Competition’s head of cartel enforcement”, Law Leaders Europe, GCR, Brussels, 28-29 June.

MacCulloch, A and B Wardhaugh (2012), “The baby and the bathwater - the relationship in competition law between private enforcement, criminal penalties, and leniency policy”, working paper.

Marvão, C and G Spagnolo (2015), “What do we know about the effectiveness of leniency policies? A survey of the empirical and experimental evidence”, in Beaton-Wells, C and C Tran (eds), Anti-Cartel Enforcement in a Contemporary Age: The Leniency Religion, Hart Publishing.

Marvão, C and G Spagnolo (2023), “Leniency inflation, Cartel damages, and Criminalization”, Review of Industrial Organization 89, 102932.

Moreau, F and L Panon (2023), “The Aggregate Cost of Cartels”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Norton Rose Fulbright (2023), “The continuing rise of antitrust damages actions”, March.

OECD (2022), “OECD Competition Trends 2022”.

Thacher, S (2023), “Global cartel forecast for 2023”, Simpson Thacher & Bartlett LLP, 11 January.

Ysewyn, J and S Kahmann (2018), “The decline and fall of the leniency programme in Europe”, Concurrences Review N° 1-2018, Art. N° 86060, pp. 44-59.