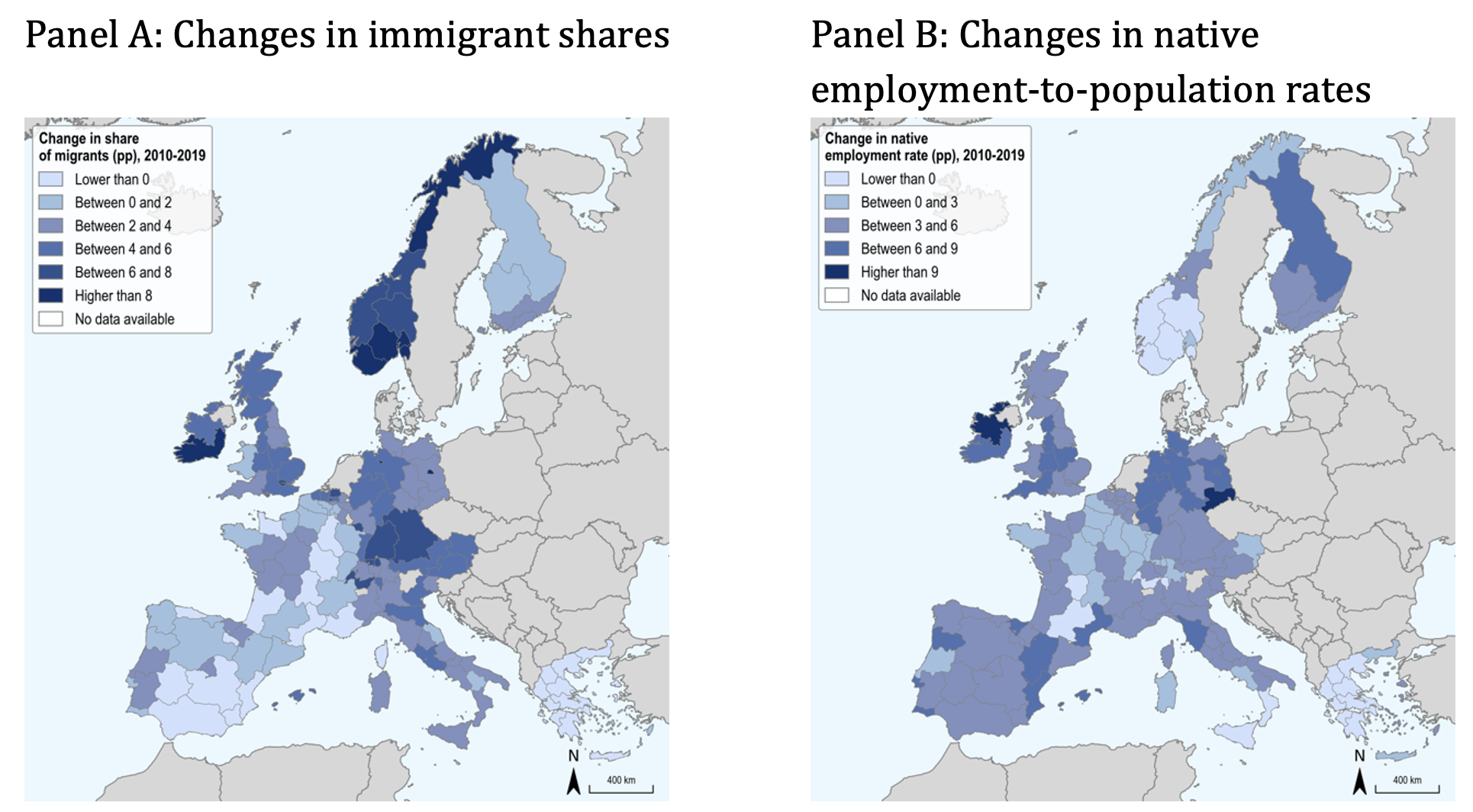

How does immigration affect employment opportunities for natives? As immigrants (or the foreign-born) make up an increasingly large share of receiving countries in Europe, the economic impact of immigration remains a topical issue. The foreign-born share of the labour force in these countries increased by 3.4 percentage points over the last decade, from 12.8% in 2010 to 16.2% in 2019, which is twice as much as in the US, where the foreign-born share of the labour force increased by only 1.6 percentage points (from 15.8% in 2010 to 17.4% in 2019). As shown in Figure 1, this increase has been uneven between and within European regions.

Figure 1 The changes in the employment rates and immigrant shares in 13 European countries between 2010 and 2019

Source: Edo and Özgüzel (2023)

In a recent paper (Edo and Özgüzel 2023), we exploit these variations and present the first empirical evidence on the regional impact of immigration on native employment across European countries. Our analysis relies on the EU Labour Force Survey (EU LFS) covering 13 (West) European countries over the 2010-2019 period. The richness of the data allows for estimating the impact of immigration on the employment rate of natives at the regional level across multiple countries. This perspective provides a wealth of information to understand the labour market effects of immigration better and whether these effects are more pronounced in regions with more protective labour market institutions (e.g. higher employment protection, collective bargaining, or higher union density) or in regions experiencing stronger economic expansion during the period of analysis.

The advantage of our cross-regional analysis is to account for all channels through which an immigrant supply shock in a given region can affect native employment in that region. This estimation strategy not only captures the ‘own’ effect of a particular supply shift on the employment of competing workers. It also captures the complementary effects of the supply shock on the employment of workers with different skills. However, this analysis could lead to misleading interpretations if immigrants chose their region of residence based on economic considerations or if natives responded by migrating to other local labour markets (Borjas et al. 1997, Dustmann et al. 2005).

To address the potential bias arising from the endogeneity of immigrant location choices, we collected and harmonised census data for 13 countries to measure the historical distribution of immigrants in 1990 by country of origin across European regions to predict the regional distribution of immigrants during the analysis period. The instrumental variable (IV) strategy relies on the fact that the presence of earlier migrants partly determines immigrant settlement patterns, while the historical distribution of immigrants in 1990 should be uncorrelated with contemporaneous changes in regional economic conditions (Altonji and Card 1991, Card 2001). We perform a series of tests to address issues raised by Jaeger et al. (2018) and Goldsmith-Pinkham et al. (2020), confirming our IV strategy's validity. Finally, we show that immigration did not affect native internal mobility across European regions over the period considered. Therefore, our estimated employment effects are unlikely to be biased by the reallocation of natives across regions.

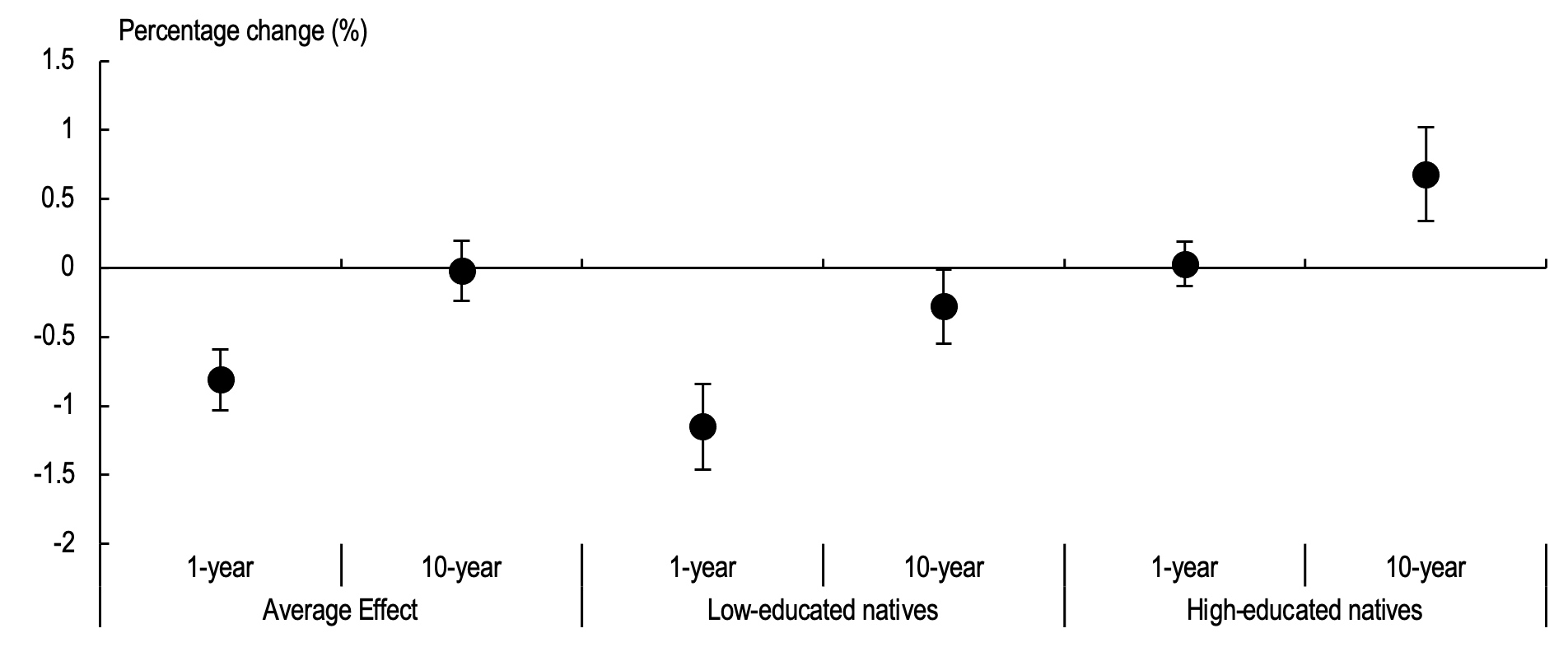

We uncover four significant findings. First, immigration has a detrimental impact on the employment rate of natives in the early years following the supply shock. In the short term, a 1% immigration-induced increase in the size of the labour force in a given region reduces the employment-to-population rate of natives in that region by 0.81% (see Figure 2). Yet, the native employment response to immigration is more negative in the short term when examining 1-year (or annual) fluctuations compared to 2-year and 3-year variations. The short-term impact of immigration disappears in the longer run when examining 5-year or 10-year variations. This employment dynamics induced by immigration is consistent with standard theory indicating that economic adjustments following immigration are not necessarily immediate and can take some time (Borjas 2013).

Second, the labour market effects of immigration differ by educational group. The impact of immigration on the employment rate of highly educated natives is zero in the short run and positive in the longer run, while the effects are negative among low-educated natives in the short run and much weaker in the longer run (see Figure 2). It is not surprising to find an adverse impact on the employment of low-educated native workers as the degree of competition between natives and immigrants within the low-skill segment of the labour market tends to be stronger (Dustmann et al. 2013, Peri and Sparber 2011). In sum, immigration to Europe in the last decade increased the employment opportunity gap between high- and low-educated natives.

Third, the impact of immigration on employment is weaker in regions with stricter labour market institutions. We interact the regional share of immigrants with three institutional measures indicating whether the region is located in a country with a high level of employment protection or union density (i.e. in the top 50% in 2010), or whether wage bargaining takes place predominantly at the sectoral/country level (as opposed to the firm level). We find that higher levels of employment protection and collective bargaining coverage dampen the employment effect of immigration by shielding native workers in the short and longer run. In contrast, a higher degree of union density does not matter when determining the employment impact of immigration.

Figure 2 The labour market effects of immigration are uneven across time and workers with different levels of education

Estimated effect of a 1% increase in the labour supply due to immigration on the log employment-to-population rate of natives by level of education, 2010-19, NUTS2 regions

Finally, economically dynamic regions are better equipped to absorb immigration. We classify European regions into two categories based on their economic vitality, using a ‘high GDP growth’ indicator to differentiate between those with strong and weak economic performance. This classification is determined by ranking regions according to their GDP changes between 2010 and 2019. The top 25% are designated as ‘high GDP growth’ regions, while the remaining 75% are considered regions with comparatively weaker economic dynamism. In the short term, the fastest-growing regions show relatively modest employment effects in response to immigration, but they experience employment gains in the long term. This outcome underscores the significant role that economic dynamism plays in shaping the impact of immigration on the labour market.

Our findings reveal the intricate and diverse impact of immigration on the employment of natives in European countries. While the employment impact of immigration can be negative in the short run, it diminishes over time and vanishes after some years. Furthermore, the employment response to immigration varies by educational level and places according to their institutional features. From a policy perspective, our study highlights the importance of adopting a nuanced and targeted approach to immigration policies. As the labour market consequences for natives are uneven across groups and places, targeted policies that consider these heterogeneous impacts can mitigate any potential short-run adverse labour market effects on low-educated workers and economically lagging regions and ensure that the entire population benefits from the economic gains associated with migration.

References

Altonji, J and D Card (1991), “The Effects of Immigration on the Labour Market Outcomes of Less-skilled Natives”, NBER Working Paper 3123.

Borjas, G J, R B Freeman, L F Katz, J DiNardo and J M Abowd (1997), “How much do immigration and trade affect labor market outcomes?”, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1997(1): 1-90.

Borjas, G (2013), “The analytics of the wage effect of immigration”, IZA Journal of Migration 2(1): 1-25

Card, D (2001), “Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labour market impacts of higher immigration”, Journal of Labour Economics 19(1): 22-64.

Dustmann, C, F Fabbri and I P Preston (2005), “The impact of immigration on the British labour market”, Economic Journal 115(507): F324-F341.

Dustmann, C, T Frattini and I P Preston (2013), “The effect of immigration along the distribution of wages”, Review of Economic Studies 80(1): 145-173.

Edo, A and C Özgüzel (2023), “The impact of immigration on the employment dynamics of European regions”, Labour Economics 85, 102433.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P, I Sorkin and H Swift (2020), “Bartik instruments: What, when, why, and how”, American Economic Review 110(8).

Jaeger, D, J Ruist and J Stuhler (2018), “Shift-share instruments and the impact of immigration”, IZA Discussion Paper 11307.

Peri, G, and C Sparber (2011), “Highly educated immigrants and native occupational choice”, Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 50(3): 385-411.