There is no longer any debate about whether some multinational enterprises (MNEs) avoid taxes by shifting profits to tax havens. Several methods used to move profits have been identified, including manipulating transfer prices, the strategic location of intellectual property, and the use of internal debt. According to Tørsløv et al. (2018), the use of such strategies allows multinationals to move nearly $1 trillion in profits to tax havens each year. Low-tax countries – and tax havens in particular – are the destinations for these tax-avoiding profits (see Acciari et al. 2021). What is less understood, however, is what happens to the money not spent on taxes. Put simply, if shifting profits leaves more money at the firm's disposal, where does it show up?

In a new paper (Alstadsæter et al. 2022), we investigate one possibility: that at least some of it ends up in workers' pockets via higher wages. To do so, we use matched employer-employee administrative data from Norway to assess if there is any evidence of a wage premium associated with working for a profit shifter.

Wage premium to workers in profit shifting firms in service industries

Fuest et al. (2018), Saez et al. (2019), and Carbonnier et al. (2022) find that lower domestic taxes mean higher wages for the workers, with higher skill workers gaining the most. We build on this by recognising that for multinationals, their tax bill does not just depend on domestic policy but on the global tax environment to which they are exposed. In particular, having a link to a tax haven provides a firm with the ability to lower its global tax burden. In addition to broadening the understanding of the impacts of profit shifting, our results help to frame the fact that MNEs generally pay higher wages than domestic firms and that globalisation has distributional wage effects (Hummels et al. 2014, Klein et al. 2013, Souillard 2020, Lopez-Forero 2021, Keller and Olney 2021, Dorn and Levell 2022).

With this in mind, we compare workers' wages in firms linked to a tax haven affiliate (‘profit shifters’) to those that are not. Although it may be presumptive to assume that having a haven affiliate means a firm is actively profit shifting, our data indicate that Norwegian firms with a haven affiliate have a return on assets 26% lower than comparable firms, i.e. their profits are markedly lower than what we would otherwise expect. Thus, the data suggest that having a haven affiliate is a strong indicator of potential profit shifting.

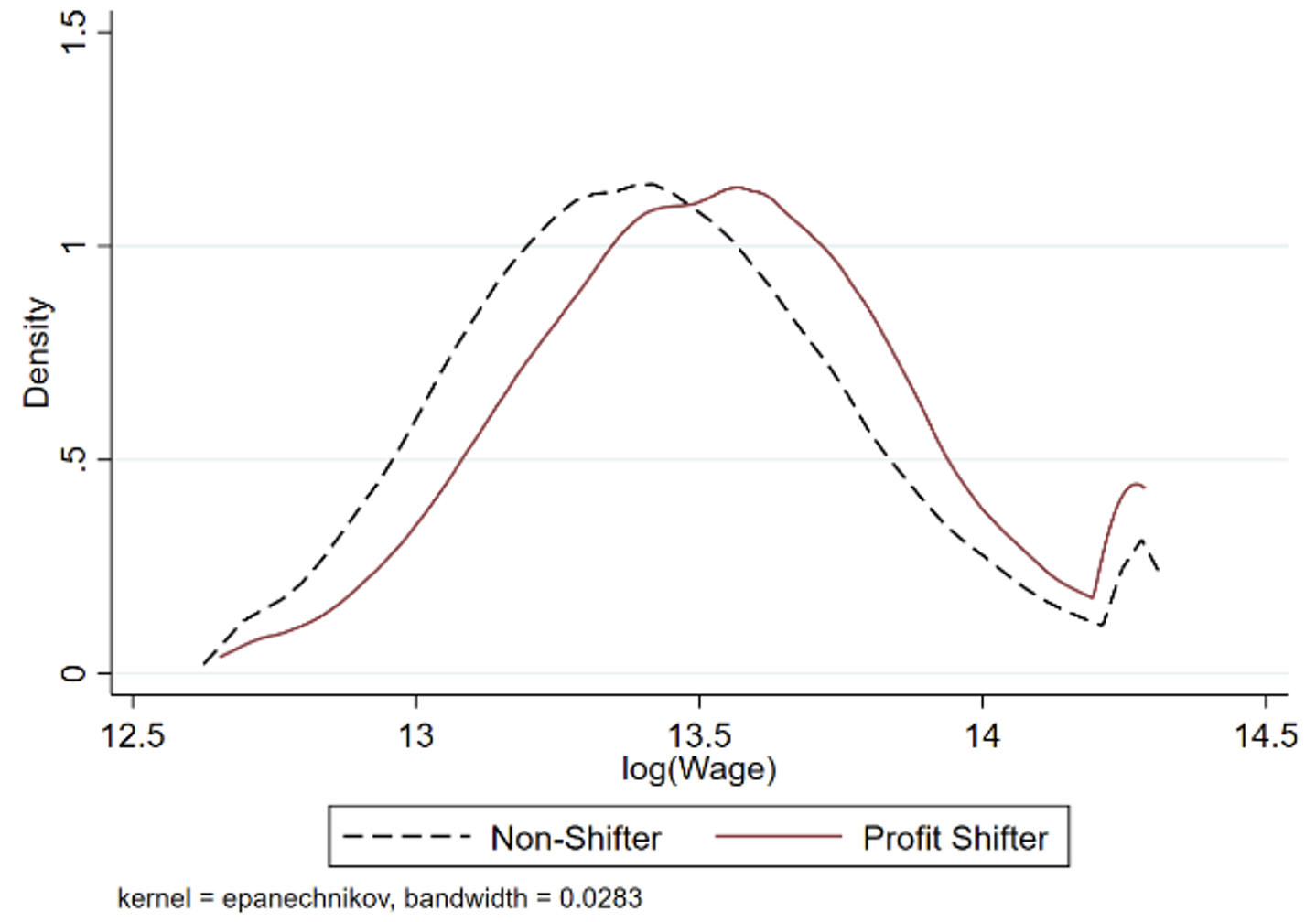

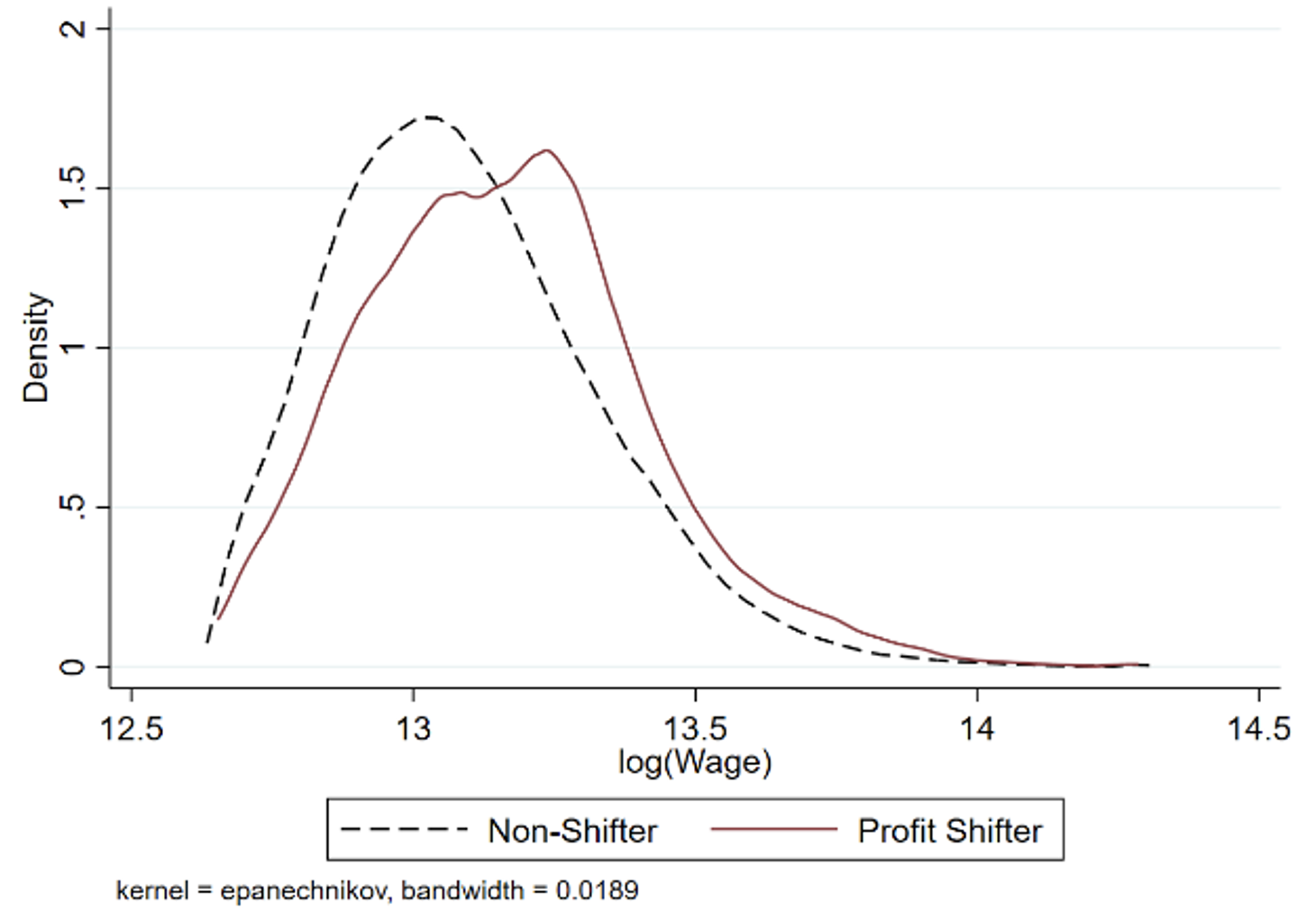

As a first pass, we compare the wage distributions for shifters and non-shifters. Considering the domestic tax windfall literature which finds different effects across skill levels, we do so separately for the high-skill (managers, professionals, and technicians) and low-skill occupations (remaining occupations). When we do so, we find that this is especially visible for the high-skill occupations, particularly those who are paid the most. As shown in Figure 1, the wage distribution of profit shifters is to the right of non-shifters, i.e. they pay higher wages.

Figure 1 Wage distributions for profit shifters and non-shifters

a) High-skill occupations

b) Low-skill occupations

This comparison, however, does not control for other factors. With this in mind, we then turn to regression analysis. When doing so, we also differentiate between the manufacturing and services sectors. We do so out of the belief that intangible assets play a significant role in profit shifting, meaning that firms in services may find profit shifting relatively easier, a result consistent with the findings of Delis et al. (2021).

For services firms, our estimates suggest a 2% wage premium for the average worker. In contrast, we find no significant wage premium for the average worker in manufacturing. This wage premium in services is robust to comparing profit shifters to other firms that do significant business with tax havens but do not have an affiliate there. This indicates that the difference is driven by existence of the haven affiliate, not just doing business with havens. Likewise, the wage difference remains when comparing shifters (i.e. multinationals with a haven affiliate) to multinationals without haven affiliates. Thus, the wage premium is associated with the tax haven affiliate, not simply being a multinational. Since moving profits to a tax haven only makes sense when the recipient is affiliated with the sender, this reinforces that the link is between wages and profit shifting. Furthermore, given that the establishment of a tax haven affiliate is a choice, we use an event study where the results argue against the possibility that our results are due to some other difference between firms establishing haven affiliates and other firms.

Highly skilled and highly paid workers benefit more from their employer’s profit shifting

While this initial foray only finds a significant wage premium in services, this is an average effect across all workers. When we allow the wage difference to vary by occupation, we find that managers, professionals, and technicians earn about 2% more when working for a shifter and that this pattern that holds for both services and manufacturing. In addition, even when compared to other managers, CEOs enjoy a markedly higher wage premium that amounts to nearly 41% of the median annual wage. Thus, even within a firm, profit shifting is associated with greater income inequality.

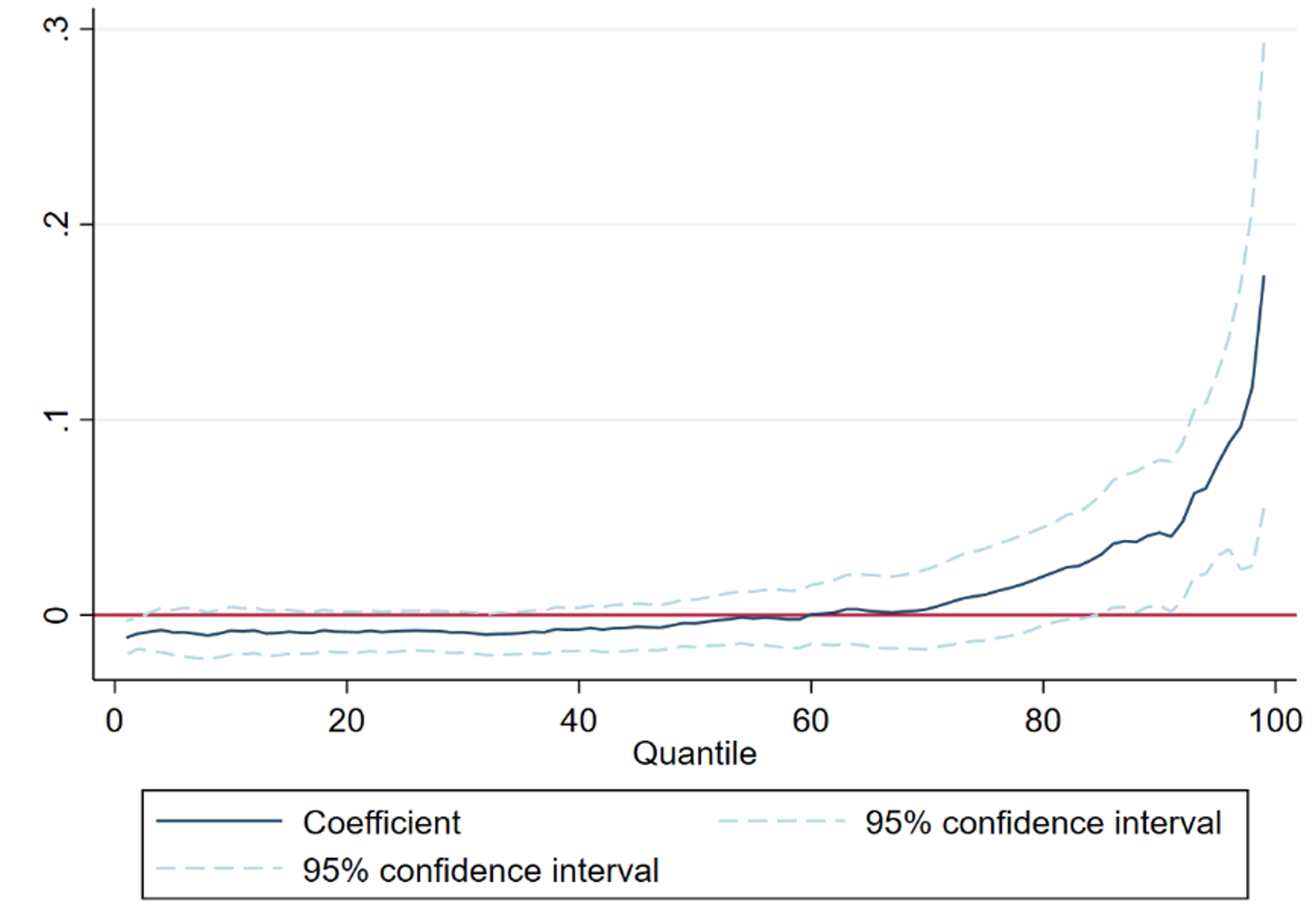

Turning to an alternative way of comparing across workers, we use their wage level rather than their role in the firm. For services, the estimated wage premium across the wage distribution is illustrated in the figure below. As shown, the estimates find no significant wage premium until the 85th percentile, i.e. wages are higher for shifter employees, but only those already in the top 15% of the wage distribution. Again, this suggests that shifting may benefit the highest paid workers and contribute to inequality.

Figure 2 Estimated wage premium across the wage distribution (services)

Back-of-the-envelope calculation of tax revenue consequences

Overall, we find a wage premium for employees of profit shifters, albeit only for those already earning higher wages. What then do these higher wages mean for government tax revenues? Using a back-of-the envelope calculation, we estimate that in 2018 profit shifting led to an extra 449.2 million NOK in wages which itself would have generated an extra 273.1 million NOK in income and social security taxes. That increase however, pales in comparison to estimates of the corporate tax losses due to profit shifting. According to Tørsløv et al. (2018), 43.7 billion NOK were shifted out of Norway in 2015, amounting to a tax loss of 9.6 billion NOK. Thus, the increase in personal taxes would only offset a mere 2.8% of the lost corporate taxes. Therefore, while some of the revenue losses are recouped via higher personal taxes, profit shifting is still a net drain for the Norwegian tax take. When this is combined with the potential income inequalities our analysis uncovers, we believe that public outcry against profit shifting is unlikely to abate any time soon. This may then provide continued motivation for changes in the global tax system aimed to reduce profit shifting (see Djankov 2021 and Vaitilingam 2021 for discussion).

References

Acciari, P., Bratta, B., Santomartino, V. (2021), "New patterns of profit shifting emerge from country-by-country data", VoxEU.org, 28 June.

Alstadsæter, A, J Brun Bjørkheim, Davies, and J Scheuerer (2022), "Pennies from haven: Wages and profit shifting", Oxford University Centre for Business Taxation WP22/04.

Carbonnier, C, C Malgouyres, L Py, and C Urvoy (2022), "Who benefits from tax incentives? The heterogeneous wage incidence of a tax credit", Journal of Public Economics 206, 104577.

Delis, F, M Delis, L Laeven, and S Onega (2021), "Global evidence on profit shifting: The role of intangible assets", VoxEU.org, 11 October.

Djankov, S (2021), "Simpler approaches to a global tax plan", VoxEU.org, 8 October.

Dorn, D and P Levell (2022), "Changing views on trade's impact on inequality in wealthy countries", VoxEU.org, 14 February.

Fuest, C, A Peichl, and S Siegloch (2018), "Do higher corporate taxes reduce wages? Micro evidence from Germany", American Economic Review 108(2): 393–418.

Hummels, D, R Jørgensen, J Munch, and C Xiang (2014), "The wage effects of offshoring: Evidence from Danish matched worker-firm data", American Economic Review 104(6): 1597–1629.

Keller, W and W W Olney (2021), "Globalization and executive compensation", Journal of International Economics 129, 103408.

Klein, M W, C Moser, and Urban, D M (2013), "Exporting, skills and wage inequality", Labour Economics 25: 76–85.

Lopez-Forero, M (2021), "Aggregate inequalities and tax havens: Things are not always what they seem", Mimeo.

Saez, E, B Schoefer, and D Seim (2019), "Payroll taxes, firm behavior, and rent sharing: Evidence from a young workers’ tax cut in Sweden," American Economic Review 109(5): 1717–63.

Souillard, B (2020), "Profit shifting, employee pay, and inequalities: Evidence from US listed companies", SSRN Working Paper 3750623.

Tørsløv, T R, L S Wier, and G Zucman (2018), "The missing profits of nations", NBER Working Paper 24701.

Vaitilingam, R (2021), "Corporate taxes: Views of leading economists on profit-shifting, tax base, and a global minimum rate", VoxEU.org, 6 July.