Since 2021, inflation has risen sharply across many advanced economies. This reflects multiple factors, including energy prices, supply disruptions, and labour market tightness (see Bank of England 2023, Cerrato and Gitti 2023, Dinghra and Page 2023, and Soldani et al. 2023 for some recent commentary). In this column, we use survey data from the Decision Maker Panel (DMP) to investigate how firms have set prices during this recent period of high inflation. We first asked firms how they set prices. We then contrast the experience of firms who are primarily setting prices in response to events against those that tend to change prices at fixed intervals. This builds on our previous work on using the DMP survey to analyse recent developments in inflation (Bunn et al. 2022, Thwaites et al. 2022, Yotzov et al. 2022, 2023).

Prices are usually thought to be sticky because of the presence of some nominal rigidities, which imply that prices cannot adjust instantaneously or costlessly. These can be categorised under two main headings: state-dependent and time-dependent models. In a time-dependent model, the probability of a price change is independent of demand or costs and only changes at fixed intervals (Taylor 1980) or with a fixed probability in each period (Calvo 1983). In a state-dependent model, prices respond to changes in demand or costs, but do not adjust continually because firms have to pay a ‘menu cost’ or similar to adjust their price (Mankiw 1985). When shocks are small, state and time-dependent models have quite similar properties, but the differences are more distinct when the shocks are large (Alvarez et al. 2016). In particular, the pass-through of shocks to prices can be faster and increase with the size of the shock in a state-dependent model as it becomes more likely firms will pay the adjustment cost when shocks are big. That is not the case in a time-dependent model where the speed of adjustment is independent of the size of the shock.

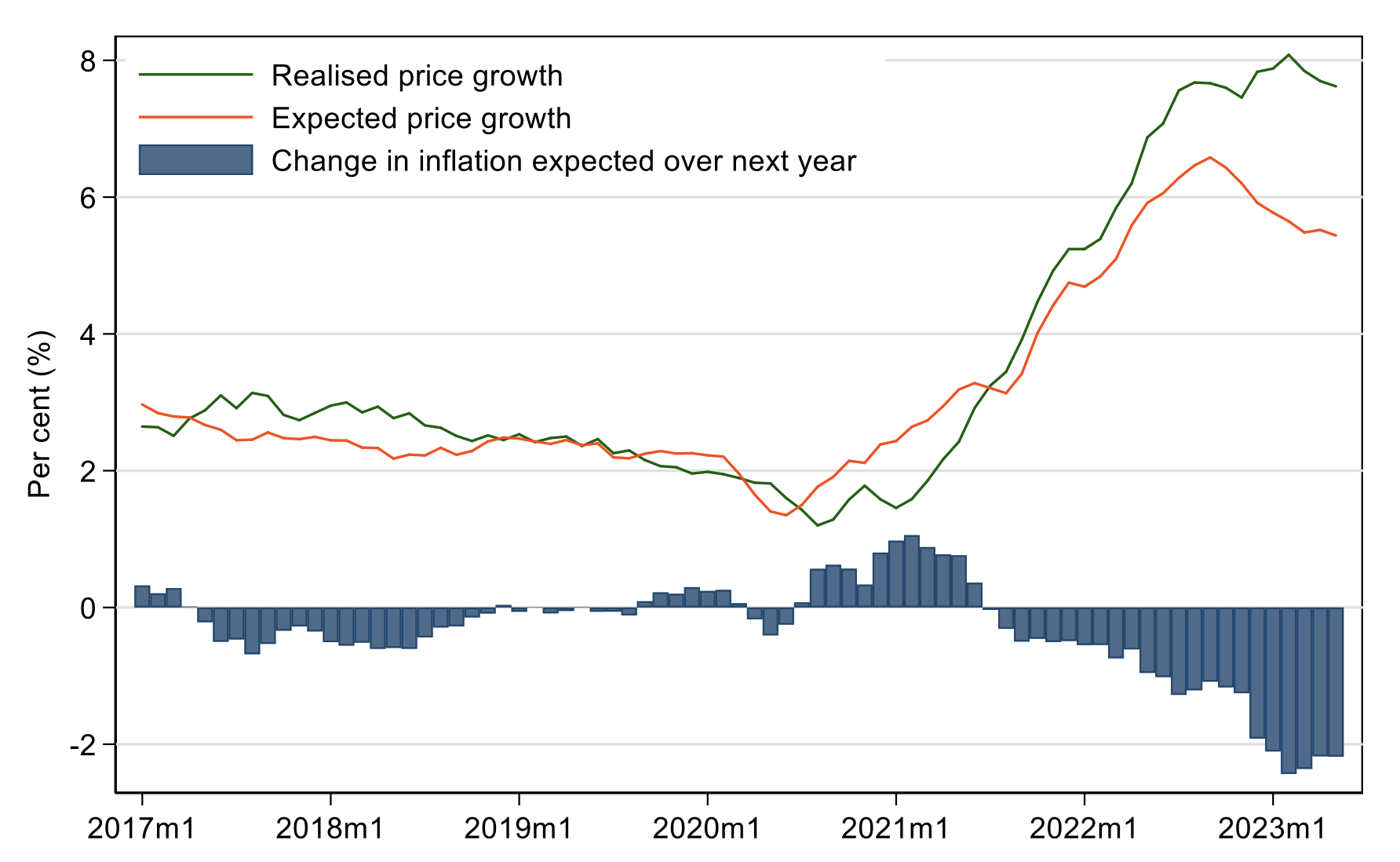

Figure 1 Realised and expected own price growth

The DMP is a large and representative survey of businesses across the UK, receiving around 2,500 responses a month. It was established in 2016, and is run by the Bank of England together with the University of Nottingham and Stanford University.

It includes regular questions asking firms how the average price that they charge has changed over the last year and about their expectations for next year. Although the DMP inflation data cover economy-wide output prices, not just those from consumer-facing firms, they follow a similar trend to official UK CPI data. Average own-price inflation rose from just under 2% in early 2021 to a peak of 8% in early 2023 (Figure 1).

Firms expected their own-price inflation to fall by just over two percentage points over the next year in the latest data for the three months to May.

State- versus time-dependent price setting

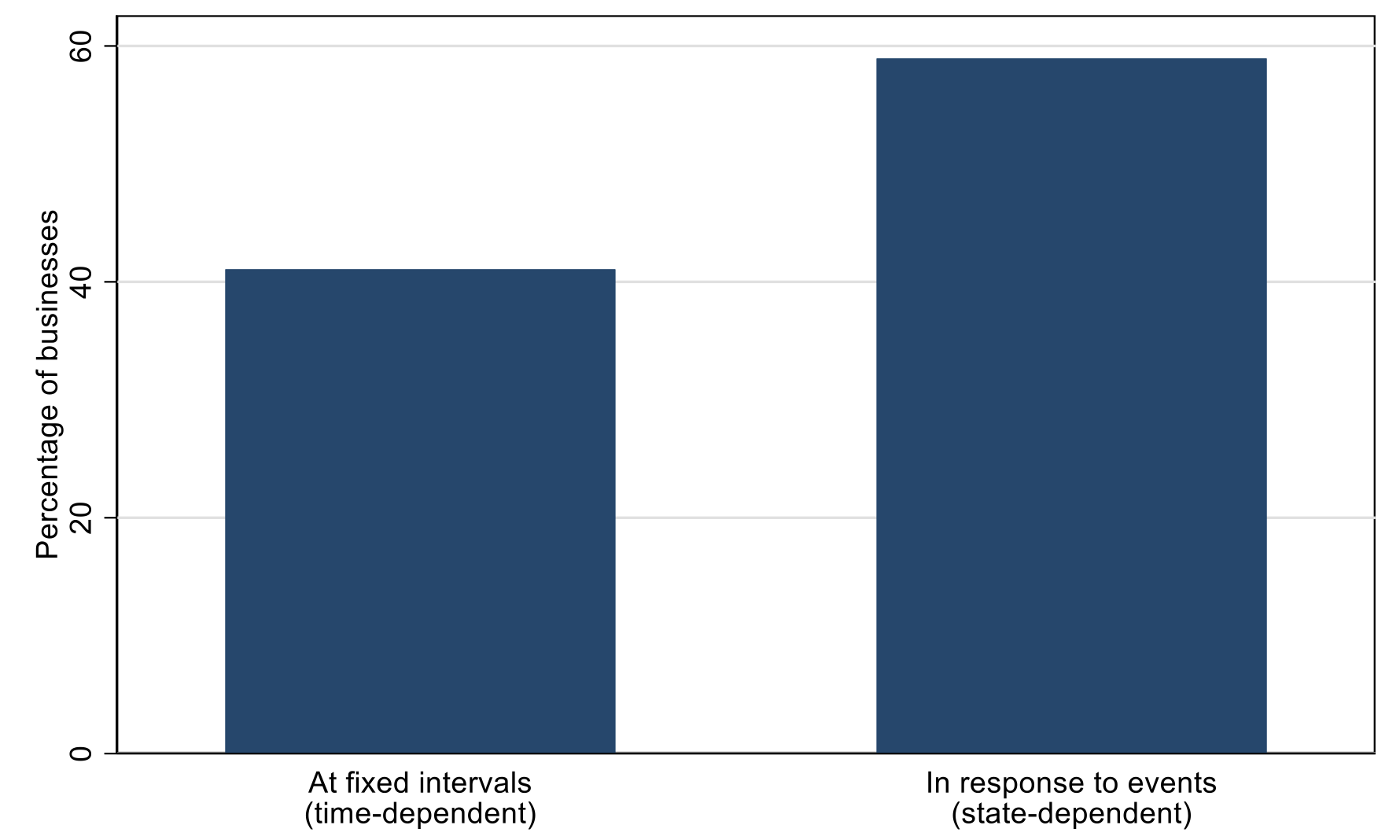

To help understand how firms typically set prices, DMP members were asked between February and April 2023 whether their businesses: (1) "Mostly change prices in response to specific events (e.g. changes in costs or demand)"; or (2) "Mostly change prices at fixed intervals (e.g. once a year or once a quarter, etc.)". There was a 60-40 split in favour of state-dependent pricing (option 1) rather than time-dependent (option 2), as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 How firms typically set prices

Goods producers were around three times more likely to say that they primarily use state-dependent pricing, whereas for service providers the split between state and time-dependence was roughly equal. By industry, construction, followed by wholesale and retail, and accommodation and food had the highest share of state-dependent price setters (all between 70% and 80%). Healthcare and other services (which include education and personal services such as hairdressing) had the lowest state-dependent share at around 25%.

Similar questions about price setting have been asked in other surveys in the past. In earlier work, around two-thirds of firms reported at least partly using state-dependent pricing in both the UK (Greenslade and Parker 2012) and the euro area (Fabiani et al. 2006). Our results are not obviously out of line with these previous studies, although the earlier estimates include firms that use both state and time-dependent pricing. In an environment where the shocks are large, the state-dependent element may have become more critical for firms which use a mixed strategy.

Frequency of price changes

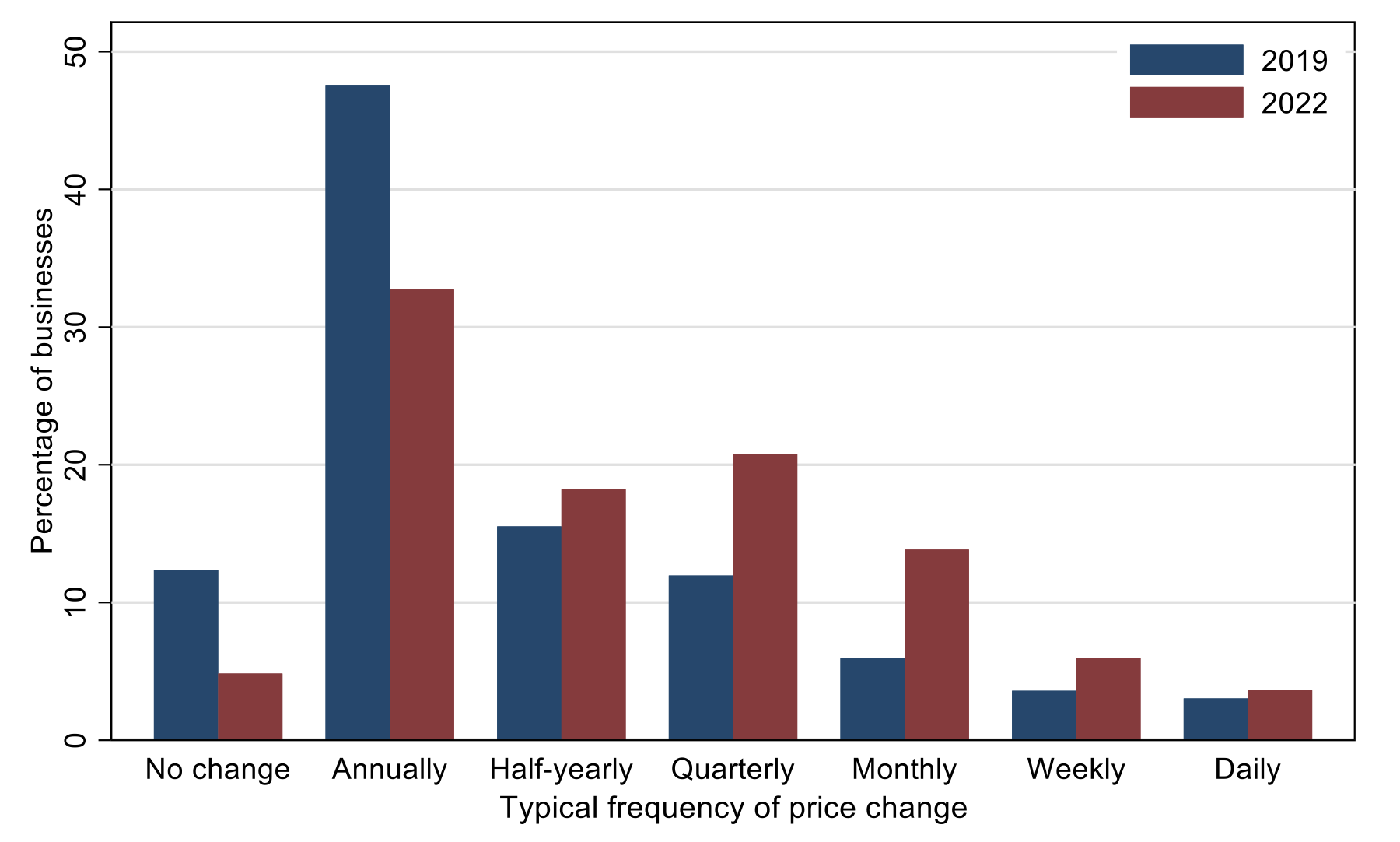

State versus time-dependent pricing models have contrasting predictions around how often prices change. In a time-dependent model, the frequency of price changes is constant over time. However, in a state-dependent model, prices should change more often in response to large shocks to costs or demand. To test this, we also asked a survey question on how often firms typically changed their prices in both 2019 and 2022.

Firms reported that prices changed more often in 2022, when inflation was much higher, than in 2019 (Figure 3). That is also consistent with evidence from UK CPI microdata.

Most of the increase in the frequency of price changes in the DMP data was in state-dependent price-setting firms: an average of 49% of their prices changed each month in 2022, compared to 31% in 2019. The corresponding change for time-dependent price-setters was a more modest increase from 11% to 17%.

Figure 3 Frequency of price changes

Inflation dynamics

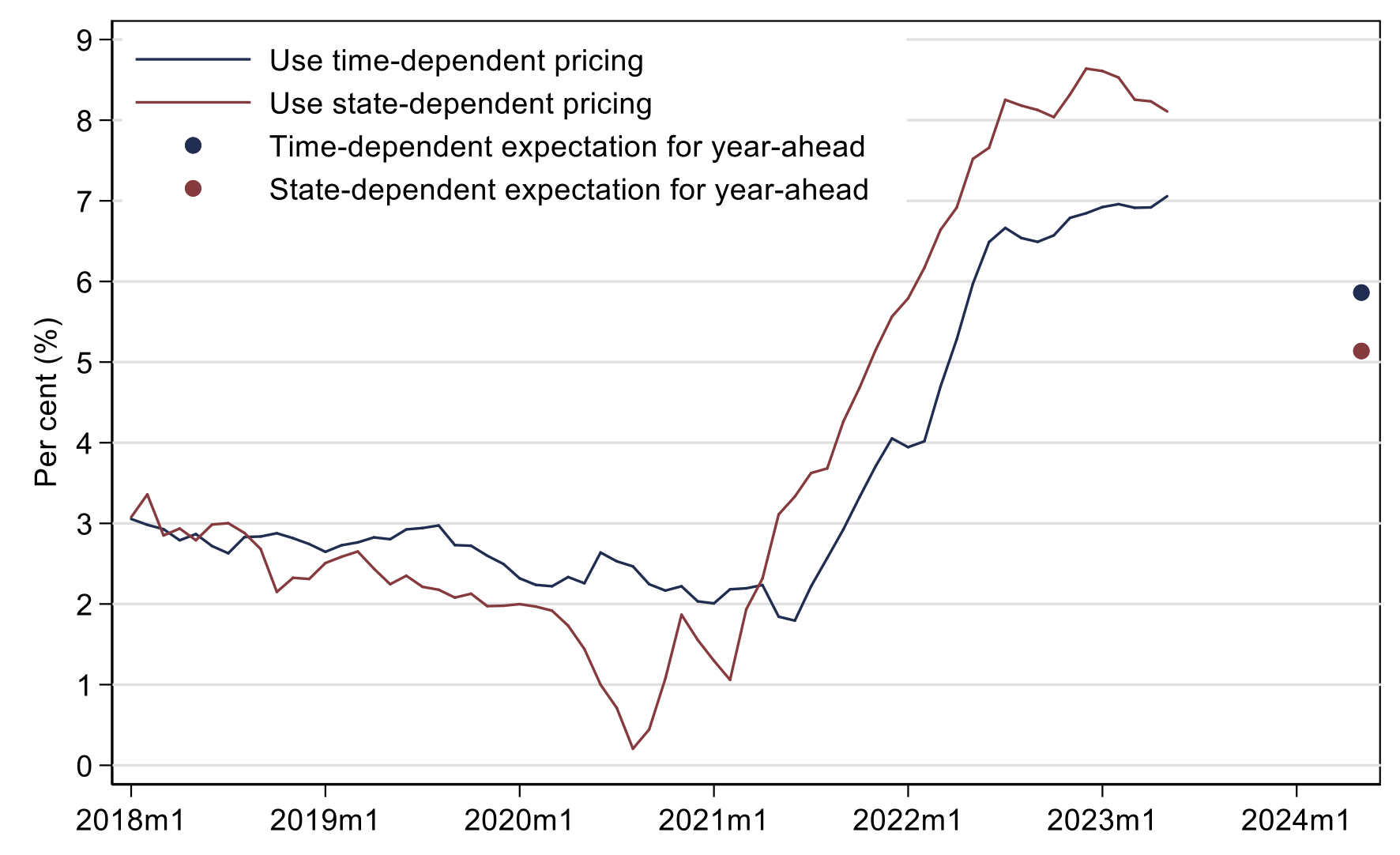

Firms that identify as using state-dependent pricing in the DMP saw a larger and earlier rise in inflation than time-dependent firms (Figure 4). Since 2021 Q2, the average inflation rate of state-dependent firms has been around 1.5 percentage points higher than for time-dependent businesses, having been lower in 2020.

Looking forward, state-dependent firms expect a larger fall in their own price inflation over the next year. The markers on the right of Figure 4 show that state-dependent firms expected their own-price inflation to fall by around three percentage points over the next year in the three months to May, compared to a fall of only one percentage point for time-dependent firms.

Figure 4 Inflation rates by how firms set prices

The earlier initial rise in inflation and then a bigger expected fall over the next year for state-dependent firms fits well with the prediction of faster pass-through for this group following a large shock. It is possible that these different groups of firms could also have faced different shocks. State-dependent firms have reported higher unit cost growth since 2022 H2 (unfortunately these data were not available for earlier periods). Still, the initial pass-through of these costs to inflation is also estimated to have been higher, and there is little difference in expected cost growth for the next year.

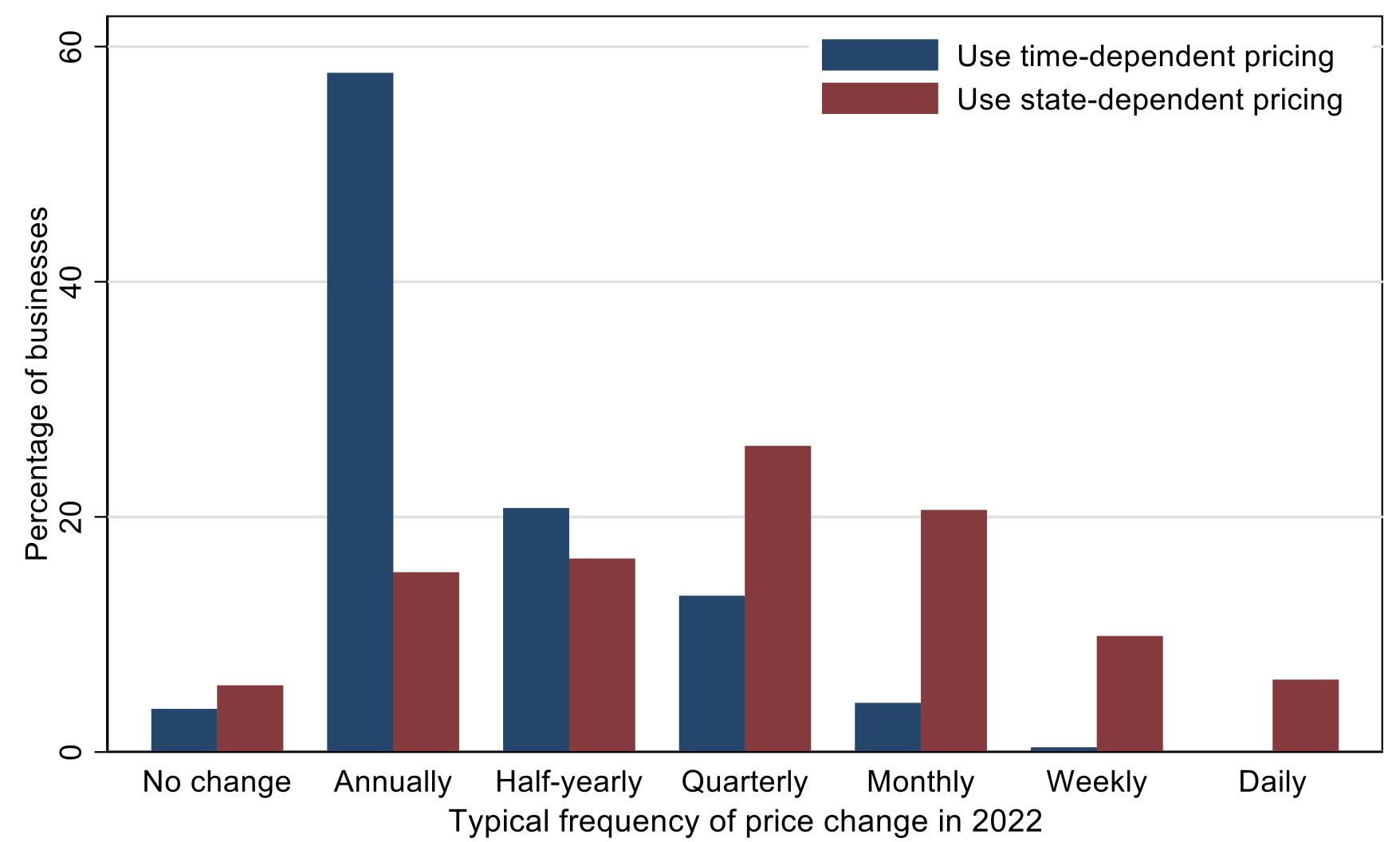

A slower adjustment to the shocks that have already taken place may help to explain why time-dependent price-setters expect greater persistence in their inflation rates over the next year. Time-dependent price-setters most commonly changed prices on an annual basis in 2022 (Figure 5). Around 60% of time-dependent firms only changed prices once or not at all in 2022, compared to just 20% of state-dependent firms.

The presence of state-dependent price-setters can introduce a non-linear response of inflation when there are large shocks as firms adjust more quickly. This could help explain why inflation has risen so quickly since 2021. If firms’ expectations are fulfilled, it could also indicate that inflation will fall more rapidly if prices changing more often means that more of the required price-level adjustment has already taken place. However, that will also depend crucially on whether the period of high inflation has led to other changes in economic behaviour such as workers or firms seeking higher nominal incomes to compensate for reductions in their real incomes.

Figure 5 Frequency of price changes in 2022 by how firms set prices

Conclusion

Using data from the Decision Maker Panel, we find that around 60% of firms have been setting prices in a state-dependent way by responding to events during the recent period of high inflation, with the remaining 40% using a time-dependent approach and only adjusting prices at fixed intervals. Consistent with the theoretical predictions in the presence of large shocks, state-dependent firms changed prices more often and saw a larger and earlier initial rise in inflation rates. Such a non-linear response could help to explain why inflation has risen as much as it has. It could also imply a faster fall in inflation, but that will also depend on other factors such as how high inflation has affected expectations for future wages and prices.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of the Bank of England or its committees.

References

Altig, D, S Baker, J M Barrero, N Bloom, P Bunn, S Chen, S J Davis, J Leather, B Meyer, E Mihaylov, P Mizen, N Parker, T Renault, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2020), “Economic uncertainty before and during the COVID-19 pandemic”, Journal of Public Economics 191, 104274.

Alvarez, F, F Lippi and J Passadore (2016), “Are State- and Time-Dependent Models Really Different?”, NBER Macroeconomics Annual 31(1): 379-457.

Anayi, L, N Bloom, P Bunn, P Mizen, G Thwaites and I Yotzov (2022), “The impact of the war in Ukraine on economic uncertainty”, VoxEU.org, 16 April.

Bank of England (2023), Monetary Policy Report, May.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, S Chen, P Mizen, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2019), “The Impact of Brexit on UK Firms”, NBER Working Paper 26218.

Bloom, N, P Bunn, P Mizen, P Smietanka and G Thwaites (2023), “The Impact of Covid-19 on Productivity”, Review of Economics and Statistics, forthcoming.

Bunn, P, L Anayi, N Bloom, P Mizen, G Thwaites and I Yotzov (2022), “Firming up price inflation”, NBER Working Paper 30505.

Calvo, G (1983), “Staggered prices in a utility-maximizing framework”, Journal of Monetary Economics 12(3): 383-398.

Cerrato, A and G Gitti (2023), “Inflation since COVID: Demand or supply”, VoxEU.org, 12 June.

Dhingra, S and J Page (2023), “Accounting for imported and domestically generated inflation: Supply chains, monetary policy, and the UK’s cost of living crisis”, VoxEU.org, 25 May.

Fabiani, S, M Druant, I Hernando, C Kwapil, B Landau, C Loupias, F Martins, T Mathä, R Sabbatini, H Stahl and A Stokman, “What Firms’ Surveys Tell Us about Price-Setting Behavior in the Euro Area”, International Journal of Central Banking 2(3).

Greenslade, J and M Parker (2012), “New Insights into Price-Setting Behaviour in the UK: Introduction and Survey Results”, The Economic Journal 122(558): F1-F15.

Mankiw, G (1985), “Small Menu Costs and Large Business Cycles: A Macroeconomic Model of Monopoly”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics 100(2): 529–538.

Soldani, E, O Causa and N Luu (2023), “The cost-of-living squeeze: Distributional implications of rising inflation”, VoxEU.org, 24 April.

Taylor, J (1980), “Aggregate Dynamics and Staggered Contracts”, Journal of Political Economy 88(1): 1-23.

Thwaites, G, I Yotzov, Ö Öztürk, P Mizen, P Bunn, N Bloom and L Anayi (2022), “Firm inflation expectations in quantitative and text data”, VoxEU.org, 8 December.

Yotzov, I, G Thwaites, P Mizen, P Bunn, N Bloom and L Anayi (2022), “Firming up price inflation”, VoxEU.org, 26 August.

Yotzov, I, L Anayi, N Bloom, P Bunn, P Mizen, Ö Öztürk and G Thwaites (2023), “Firm Inflation Uncertainty”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 113: 56–60.