Multinational enterprises (MNEs) tend to be very large and intangible-intensive firms that can choose strategically how they book activities across their affiliates around the world, with the potential to significantly distort aggregate statistics. In particular, in a context of deep financial integration and international tax competition, the growing intangible economy has provided new tools for MNEs to offshore their profits to low-tax countries.1 This, in turn, artificially minimises activity in high-tax countries, leading to underestimations of a number of aggregates including value-added, exports, and productivity.

There is growing evidence that with the deeper international financial integration process that we have observed in the past decades, complex structures aiming at reducing the tax bills of MNEs significantly distort official production statistics. For instance, Tørsløv et al. (2018), who estimate that around 40% of global profits in 2015 were shifted to tax havens, revise worldwide official statistics adjusted by profit shifting and suggest that in case of France, the trade balance deficit disappears. Furthermore, the digitalisation of activities pushing firms to invest more in intangibles has resulted in a steady rise in the importance of intangible investment relative to tangible investment over the past 20 years, which, according to Haskel and Westlake (2018), has overtaken tangible investment GDP share in major advanced countries around the 2008 global financial crisis. Despite the fact that techniques to reduce tax payments within MNEs have been around for some time, decoupling capital location from production and value location (e.g. intellectual property rights) and transfer mispricing (i.e. absence of ‘arm's-length prices’ for intangibles) have become much easier with the rapid rise of intangible capital.

To estimate the magnitude of this phenomenon in France, in a recent paper (Bricongne et al. 2021) we use firm-level data, mixing information on firms’ ownership relations (foreign and domestic, related to parents and subsidiaries), balance sheets, trade, workforce, and wage bill over 1997 and 2015. We implement a staggered difference-in-differences (DiD) approach in order to estimate the average effect of profit shifting on the level of firm productivity and its conditionality on intangible assets. Offshore profit shifting is identified from within-firm variation in the presence in tax havens across firm intensity in intangible capital, exploiting the precise establishment of firms’ new foreign presence in a tax haven or non-tax haven country. The dynamic of the productivity effect of firm presence in tax havens is assessed within a panel event study, which, by rejecting the existence of a pre-treatment trend, allows us to show that the estimates capture the tax haven entry effect and not differential trends between treated and control units.

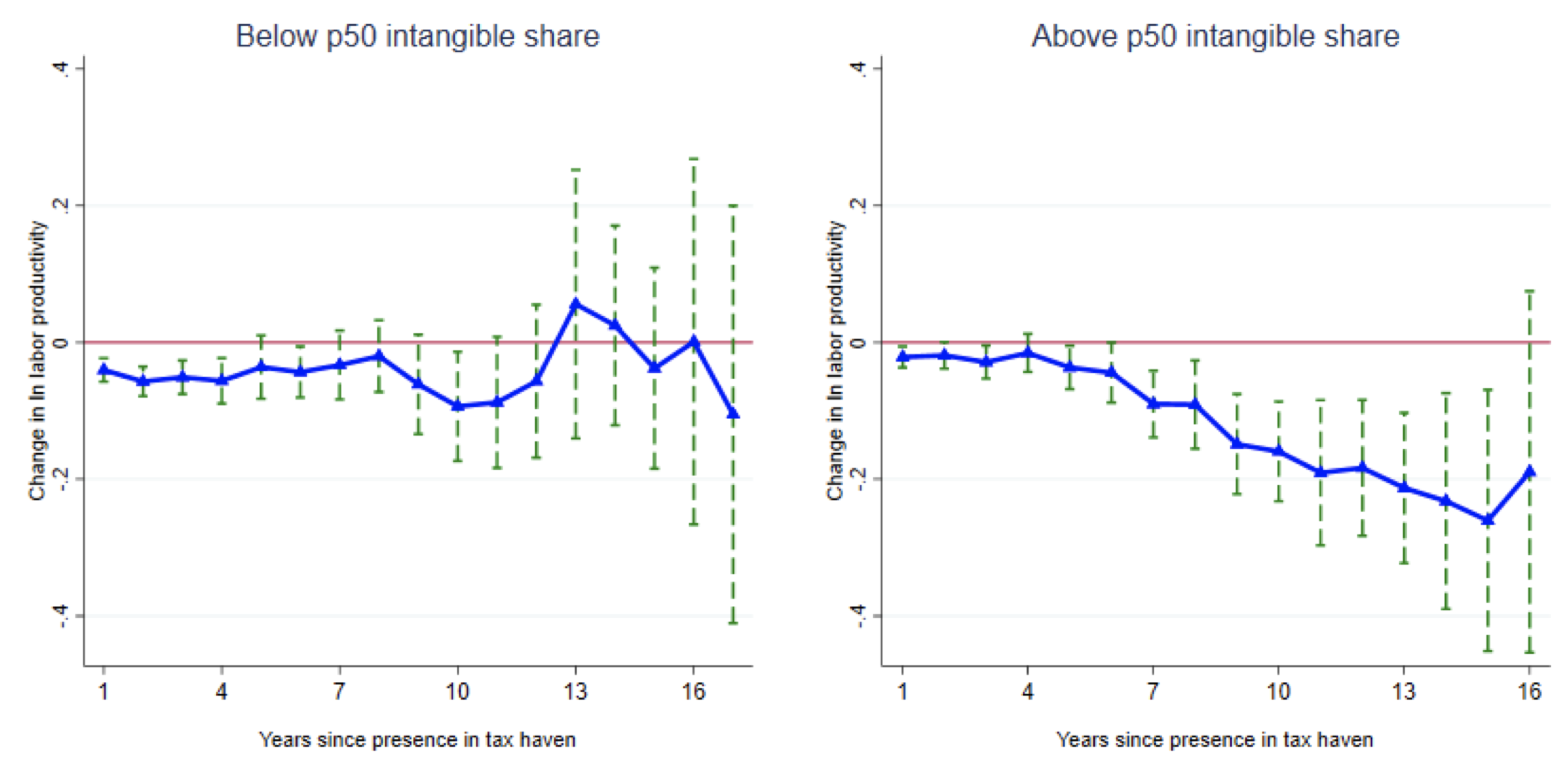

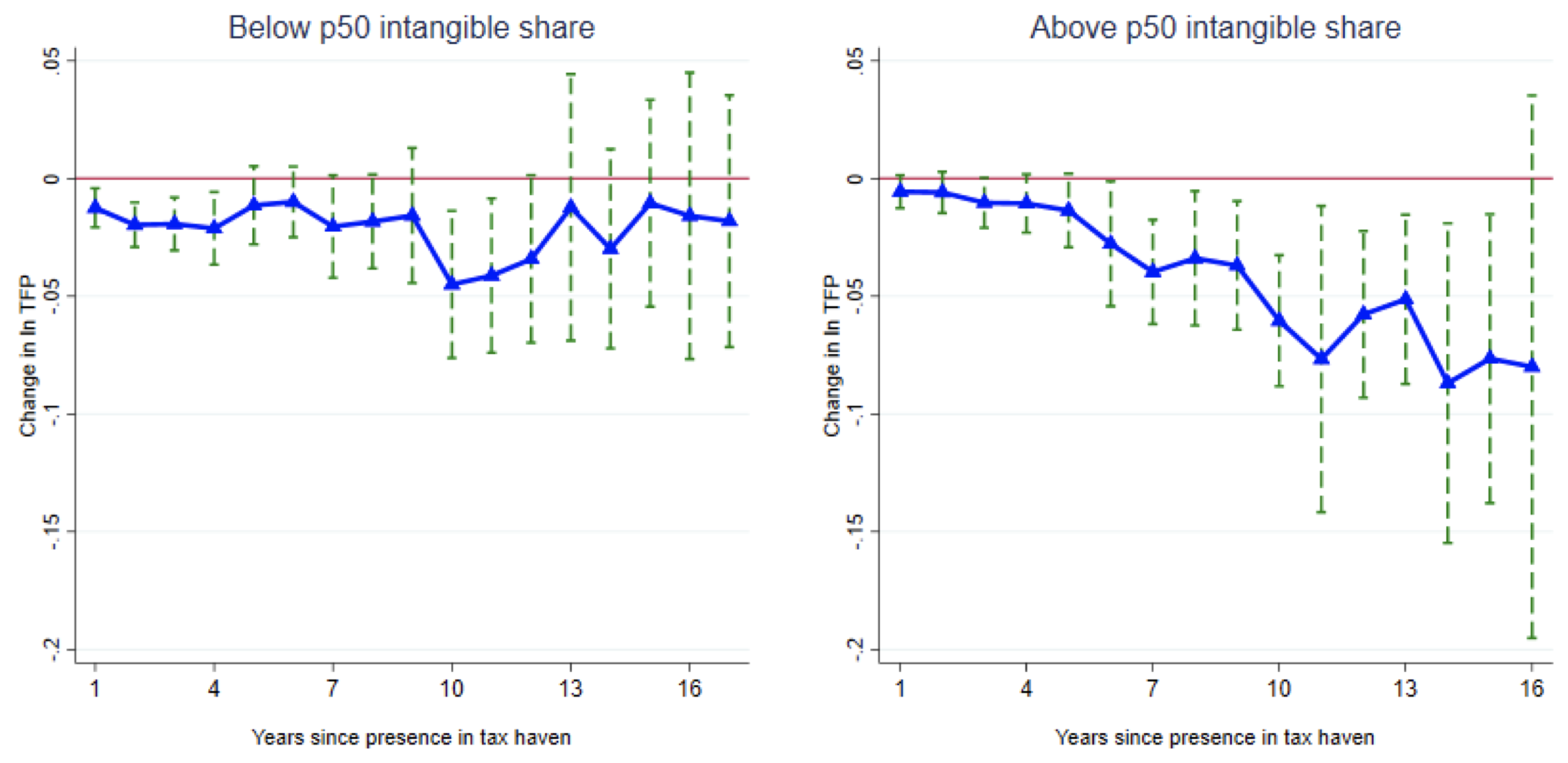

This analysis results in an average decline of 3.5% in firm labour productivity and 1.3% in firm total factor productivity (TFP), which is most likely due to a productivity mismeasurement resulting from profit shifting. The fall is especially strong for firms that are intensive in intangible capital. The level of apparent labour productivity (ALP) is on average reduced by 4.1% when a firm becomes a tax haven MNE and belongs to the group of high intangible intensity firms, while it is on average reduced by 2.7% for low intangible intensity firms. In the case of TFP, an average impact of -1.5% is estimated for firms above the median intangible intensity and around -0.9% for firms that are less intangible-intensive. Additionally, the mismeasurement has strong dynamic effects, as the decline becomes more important the longer the firm remains in a tax haven. For instance, estimates suggest that after ten years of presence in a tax haven, ALP reaches an average 11.7% drop with respect to the years before the tax haven presence, while the respective impact for TFP is around -4.8%. Again, the impact is particularly concentrated among intangible-intensive firms, as shown in Figures 1 and 2 below, which plot the estimated effect for ALP and TFP for firms above and below the median of intangible intensity.

Figure 1 Foreign presence, intangibles, and labour productivity dynamics

Figure 2 Foreign presence, intangibles, and TFP dynamics

Note: Plot of estimated coefficients of year dummies indicating MNE presence and MNE tax haven presence (solid blue line) and the corresponding confidence interval (dashed green line).

Finally, we use the weight in the aggregate value added of MNEs with a presence in tax havens and the estimated firm productivity loss due to tax haven entry from the DiD to assess the contribution of MNEs’ profit shifting to the aggregate decline in productivity growth in France. This exercise shows that micro-level fiscal optimisation of MNEs translates into a drop of 0.06% in aggregate labour productivity annual growth. This is tantamount to 9.7% of the observed aggregate annual growth in labour productivity over the sample period.

France is an interesting case as since the mid-2000s it has become a high corporate tax country with respect to its partners, despite a relatively stable tax rate. Still, the proliferation of MNEs locating in tax havens should not be specific to France. Indeed, as underlined for example by Lane and Milesi-Ferretti (2018), foreign direct investment has been expanding since the global financial crisis, driven in particular by investment in offshore financial centres. This, they argue, makes it very difficult to disentangle ‘genuine’ financial integration and portfolio diversification from complex tax evasion schemes.

Relation to existing evidence for the US

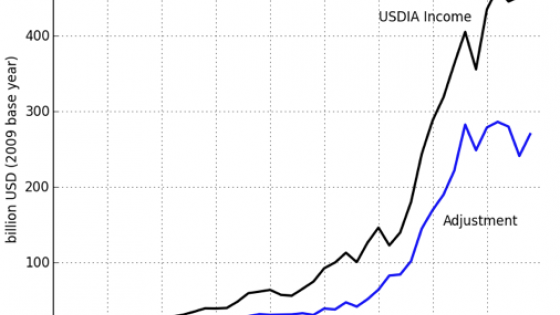

Perhaps the closest analysis to ours is Guvenen et al. (2017, 2021), who focus on US MNEs and use a formulary apportionment technique to capture the true location of economic activity. Under this method, the total worldwide earnings of US MNEs are attributed to different locations using a combination of labour compensation and sales to unaffiliated parties in each worldwide geographical location. Accordingly, in the latest version of their work, Guevenen et al. (2021) assess the impact of MNEs’ profit shifting on different aggregates and show that the effect on value added and hence, on productivity, depends on the period that is considered. They estimate that over 2004 and 2010, the profit shifting-adjusted average annual growth of labour productivity increases by 12 basis points (+6% from the unadjusted one) and decreases by 12 basis points for the period 2010-2016 (by 11% using geometric growth rate). Additionally, the adjustment is concentrated in R&D-intensive firms, being more than four times higher in R&D intensive sectors than in the aggregate economy.

In comparison, we find that in the aggregate, correcting for profit shifting increases the annual productivity growth rate by 6 basis points (+10%) over 1997 and 2015. At the level of the firm, the productivity loss appears to be, on average, 1.5 times more important for intangible intensive firms than it is for firms below the median level of intangible intensity.

Potential consequences of productivity mismeasurement

There are many potential consequences of productivity mismeasurement. First, this mismeasurement, which is higher for intangible-intensive activities, may be a factor contributing, at least partly, to explaining Solow’s paradox, according to which there is a discrepancy between measures of investment in information technology and measures of productivity and output at the national level.

Beyond measurement issues, the social and political implications of the digitisation of the economy and tax evasion by MNEs have increasingly attracted public attention and led to the BEPS framework. Interestingly, one of the first demands of society with respect to the reforms of international taxation was the implementation of a public database shedding light, country by country, on the economic activity and corresponding taxes paid by MNEs. This demand, which laid the foundation for the country-by-country reporting (CbCR) eventually implemented by the OECD, was not directly motivated by potential biases in the official statistics but mainly to improve transparency of the tax paid by MNEs. The mismeasurements associated with the offshore world therefore appear to be consubstantial issues raising both political reforms and economic clarifications.

Finally, if annual labour productivity is underestimated by around 10%, this may be used by firms as an argument to downsize wage increases, with second-round effects on consumption and growth. Conversely, for a given observed wage increase, this mismeasurement may contribute to artificially widening the gap with a reference based on productivity gains, which in turn may send a biased signal for monetary policy decisions.

References

Bricongne J C, S Delpeuch and M Lopez Forero (2021), “Productivity Slowdown and MNEs’ intangibles: where is productivity measured?” Document de recherche 21-01, Centre d'Études des Politiques Économiques (EPEE), Université d'Evry Val d'Essonne.

Clausing, K A, E Saez and G Zucman, (2020), “Ending corporate tax avoidance and tax competition: A plan to collect the tax deficit of multinationals”, Mimeo.

Guvenen F, R Mataloni, D Rassier and K Ruhl (2017), “Offshore profits and domestic productivity”, VoxEU.org, 14 June.

Guvenen F, R Mataloni, D Rassier and K Ruhl (2021), “Offshore Profit Shifting and Aggregate Measurement: Balance of Payments, Foreign Investment, Productivity, and the Labor Share”, Mimeo.

Haskel, J and S Westlake (2018), Capitalism without capital: The rise of the intangible economy, Princeton University Press.

Helpman E, M J Melitz and S R Yeaple (2004), “Export versus FDI with Heterogeneous Firms”, The American Economic Review, 94(1): 300-316.

Fons-Rosen C, S Kalemli-Ozcan, B E Sørensen, C Villegas-Sanchez and V Volosovych (2021), “Quantifying productivity gains from foreign investment”, Journal of International Economics, 131:103456.

Lane P R and Milesi-Ferretti G M (2018), “The External Wealth of Nations Revisited: International Financial Integration in the Aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis”, IMF Economic Review, 66(1): 189-222.

Tørsløv, T R, L S Wier, and G Zucman (2018), “The missing profits of nations”, Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Endnotes

1 For instance, the global average statutory corporate tax rate has fallen from 49% to 23% between 1985 and 2019 (Clausing et al. 2020).