The destruction of cities and major migration away from war-torn areas pose many challenges for the post-war reconstruction of Ukraine (e.g. Constantinescu et al. 2022). Presuming that Ukraine successfully reclaims most or all of its lost territories from Russian occupation, there will be a political drive to bring all refugees back to their hometowns and rebuild destroyed cities. Yet, as we discuss in our recent chapter in the CEPR eBook, Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, the economic reality is more complex, and simply going back to pre-war conditions may be neither possible nor desirable (Green et al. 2022).

We are optimistic that Ukraine can rebuild its cities. After all, for the entirety of human history, civilisations have rebuilt their cities – Rome after it was sacked by the Gauls; London and Chicago after great fires in 1666 and 1871; San Francisco after its great earthquake and fire of 1906; Berlin and Tokyo in the aftermath of WWII; Seoul after the Korean War; and Sarajevo in the aftermath of the Balkan Wars. Cities that have been substantially destroyed have returned to their economic and cultural dominance within a few decades – short periods within the context of modern history. Even cities recovering from near total destruction, such as Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, fairly quickly returned to their growth trajectory (Davis and Weinstein 2022). So, history gives us some reason for optimism about the prospects of rebuilding cities in Ukraine.

Yet Ukraine’s cities are different from many of the cities listed above. Ukrainian cities are poor by modern standards, and especially modern European standards. Even before the Russian annexation of Crimea and the invasion of eastern parts of Donbas in 2014, Ukraine had seen its per capita GDP fall to the second lowest in Europe, and by 2021 it had fallen behind Moldova to have the lowest GDP in Europe. Moreover, the cities in the Ukrainian east, the traditional industrial heartland, have been shedding jobs for years due to structural transformation and weakening trade with Russia. Cities such as Kharkiv and Mariupol have the problems that any rustbelt cities – let alone rustbelt cities based on Soviet industry – have. Adding to Ukraine’s woes, its economy suffers from a shrinking population. The population was declining even before the war due to low fertility and emigration, but the problem may get worse as some of the millions of international refugees may not return after the war.

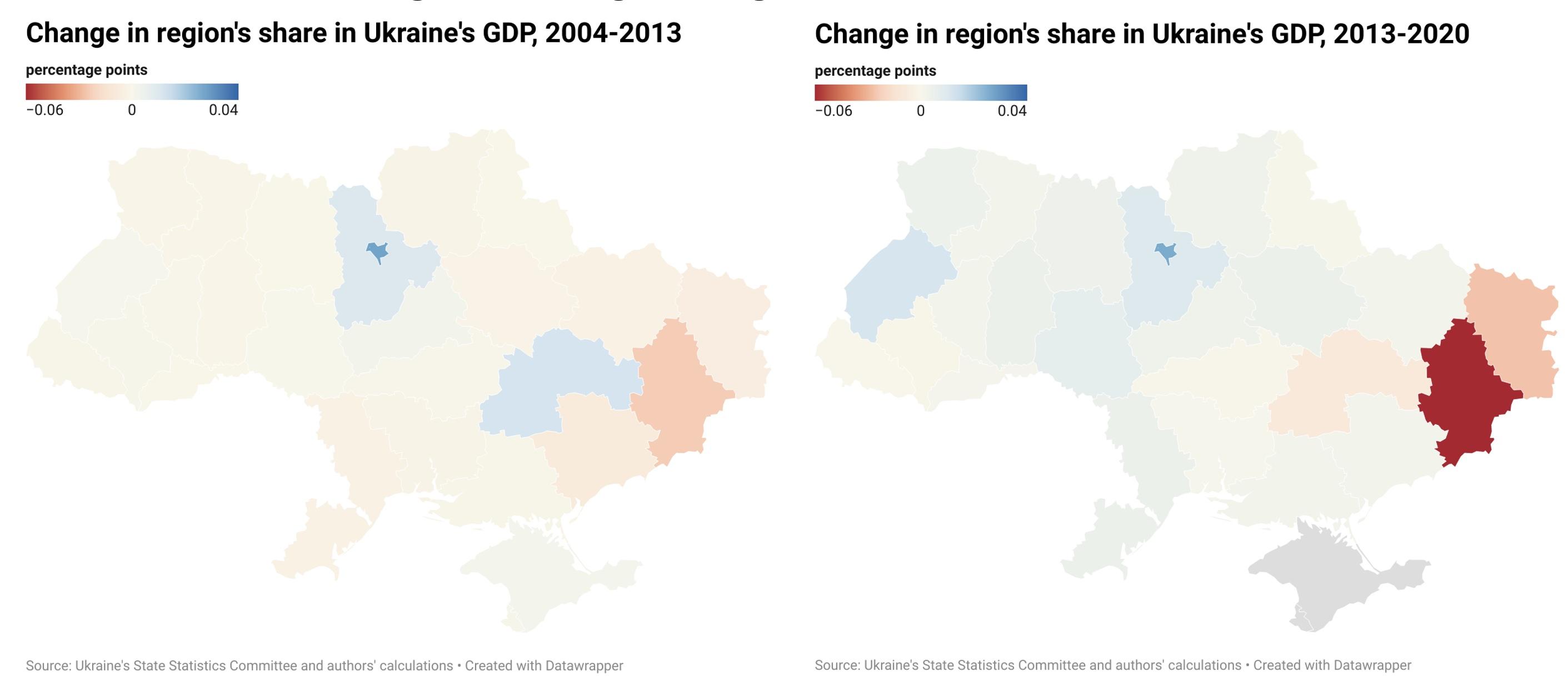

Figure 1 Changes in region’s shares in Ukraine’s GDP

We also must deal with the geopolitical reality that even though Kyiv is clearly the most productive and fastest-growing place in Ukraine, the nation’s future depends on having

healthy cities in the east of the country. For political and social reasons, Ukraine needs to rebuild cities such as Donetsk, Mariupol, and Kharkiv. Yet, many of them will emerge smaller than they were before the war. There are examples of industrial cities that shrunk successfully (Pittsburgh) and others that have not (Detroit). Successful cities have transformed their economic bases and maintained high-quality government services.

That said, in the short to medium term, the private sector will probably not provide sufficient employment to make Kharkiv and Mariupol attractive places for refugees to return to, let alone become places for new migrants. However, the Ukrainian government can locate its back-office functions nearly everywhere. This is how the Canadian, British, and US governments provide economic assistance to places that are not economically competitive and, in doing so, raise living standards in these places. We also note that literature shows universities and medical centres are strong engines of economic development (Liu 2015). Strategically placing such institutions in eastern cities may attract residents there and spur long-term growth. The recent work-from-home revolution also offers some solutions. High-amenity cities in the east and the south, such as Berdyansk, may reinvent themselves as hubs for remote workers who can perform jobs for firms in Kyiv or Lviv, while enjoying the beach.

Jobs will not be enough to attract people to eastern and southern Ukrainian cities, they will also need to be appealing places to live. On the one hand, these cities have good ‘bones’, with classic urban forms. However, they will need restoration and replacement of the housing stock, much of which is energy-inefficient, unattractive Soviet-era multifamily blocks. They also need improvements in transportation infrastructure, much of which was inherited from Soviet times. On top of that, Ukraine’s cities are highly polluted, and decarbonisation efforts will go a long way to making them more attractive places to live.

Full replacement of old housing stock will take a long time, but Ukraine can start now by focusing on providing housing for displaced populations. We propose that Ukraine provide vouchers to owners of damaged or destroyed houses and flats. These vouchers would be based on the pre-war values of the units. Such a programme would allow people to move where they wish into the type of housing unit they want. While vouchers are an efficient and effective way to house people, in order for them to work to fund new construction, Ukraine will need to develop a transparent and reliable homebuilding industry and a functioning land market. In developed countries, the construction finance system imposes discipline on real estate developers – they are not permitted to draw funds until they submit invoices documenting purchases of materials and payment of labour. Yet Ukraine’s housing finance sector is also underdeveloped. Urban land markets are controlled entirely by local governments, with land allocated in a non-market fashion, often based on political and nepotism considerations. Reforming the land market to have leaseholds sold in an open, competitive, and transparent fashion would move land use to a much more efficient regime and encourage private development.

Transportation improvements would make cities more liveable. Soviet cities were not built for cars but for pedestrians and transit users. Even in 1983, car ownership in the Soviet Union was just 32 per 1,000 people. In 2020, car ownership in Ukraine was nearly eight times as high but road infrastructure has seen only limited improvements in the last few decades. As a result, traffic congestion is a major issue in Ukraine’s large cities. One recent study found that the Kyiv metropolitan area is the 39th most congested in the world, despite not being among the world’s top 100 largest metro areas (Akbar et al. 2022). While we strongly support improvements in public transit, we believe that if Ukraine’s cities are to function as modern cities, they need to adapt to a world of greater automobile use.

Reconstruction presents an opportunity to construct some type of radial, and for larger cities, circumferential (ring roads) major arteries that will help people and goods move through the city. Ukraine should also build and improve parking facilities, which are severely lacking in its major cities. Inter-city transportation also requires upgrades. Ukraine’s road and rail networks are dense but not modern. The country needs a limited-access highway network comparable to the rest of Europe and standard gauge railroads to link to the West.

Finally, Ukraine needs to track its reconstruction progress but has unusually poor-quality data, even compared to many developing countries. Creating publicly available data on real-time indicators of urban reconstruction and local quality of life will create accountability incentives and help cities benchmark their relative progress.

References

Akbar, P, V Couture, G Duranton and A Storeygard (2022), “The Fast, the Slow and the Congestion: Urban Transportation in Rich and Poor Countries”, Working Paper.

Constantinescu, M, K Kappner and N Szumilo (2022), “Estimating the short-term impact of war on economic activity in Ukraine”, VoxEU.org, 21 June.

Davis, D R and D E Weinstein (2002), “Bones, bombs, and breakpoints: the geography of economic activity”, American Economic Review 92(5): 1269-1289.

Green, R K, J V Henderson, M E Kahn, A Nikolsko-Rzhevskyy, and A Parkhomenko (2022), “Accelerating urban economic growth in Ukraine“, in Y Gorodnichenko, I Sologub and B Weder di Mauro (eds), Rebuilding Ukraine: Principles and Policies, CEPR Press.

Liu, S (2015), “Spillovers from universities: Evidence from the land-grant program”, Journal of Urban Economics 87: 25-41.