On 31 October 1517, 500 years ago today, Martin Luther posted 95 theses on the Wittenberg Castle church door critiquing Catholic Church corruption, setting off the Protestant Reformation. The Reformation marked a critical juncture in Western history – the moment when the religious monopoly of the enormously rich and powerful Catholic Church was successfully challenged.

Social scientists have long argued that the Reformation transformed the European economy and played a role in the rise of the Western world. Yet these views have been contested, and empirical evidence on the economic consequences of one of the most important episodes in European history has been mixed (e.g. Weber 1904/1905, Tawney 1926, Becker and Woessmann 2009, Cantoni 2015, Rubin 2017).

In new research, we document a first-order consequence of the Reformation: an immediate and large secularisation of Europe’s political economy (Cantoni et al. 2017). We gather rich evidence from early modern Germany and show that:

- Human capital and fixed investment shifted sharply from religious to secular purposes after 1517, and disproportionately so in regions that adopted Protestantism.

- The growth of economic activity in the ascendant secular sector specifically reflected the interests of empowered secular territorial rulers, and came at the expense of religious elites – the hiring of lawyers rather than theologians, the building of palaces and castles rather than churches.

Conceptual framework

This consequence is surprising. How did an intensely religious movement, preaching biblical revival, produce economic secularisation? And why did resources so disproportionately shift towards the control of secular rulers? To help us understand how the introduction of religious competition during the Reformation could transform Europe’s political economy, we develop a conceptual framework.

Prior work has generally considered churches as producers of salvation, and believers as consumers (e.g. Ekelund et al. 2006). Believers pay a price, comprising financial costs in the form of tithes and donations and time spent attending masses and praying. Viewed through this lens, entry by a competitor into a hitherto monopolistic market will reduce prices in the market for salvation, leaving believers (as consumers of religion) better off. Indeed, Protestant theology offered a path to salvation that did not require the purchase of indulgences to fund expensive monasteries or a massive bureaucracy of priests.

But in addition to the ‘market for salvation’, we argue that understanding the economy-wide effects of the introduction of religious competition requires consideration of a second market – one in which secular authorities pay a price to religious elites in exchange for political legitimacy, in the form of a church’s endorsement of a ruler. The bargains in this market are at the heart of political economy across history, wherever religion provides legitimacy to political elites (Weber 1978, North et al. 2009, Chaney 2013, Rubin 2017).

The price paid by the secular lord for the church’s endorsement is typically the lord’s own endorsement of the church’s theology, as well as some set of temporal concessions: money, land, economic privileges, and political power. The ability to bargain with two providers of religiously derived political legitimacy will allow secular rulers to strike a better deal with either entrant or incumbent.

At the centre of much of the post-Reformation bargaining between secular rulers and religious elites was the massive wealth that had been held by monasteries that were closed after 1517, particularly in the Protestant territories. When the Reformation broke out, monasteries were in many territories the largest landowners in Germany, often owning as much as a third of total agricultural land. Would this wealth be reallocated to church purposes, or would it be expropriated by secular lords? Our model suggests the latter, due to the shift in the balance of power toward secular rulers.

A changed political economy in early modern Germany

Rich historical evidence confirms that secular territorial lords bargained with Protestant religious elites over the allocation of monastic resources. While Protestant theologians initially attempted to reserve these resources for religious and social purposes, the price of political legitimacy fell, and secular territorial lords were able to strike deals that left them significantly wealthier.

Protestant rulers expropriated considerable monastic wealth. In Hesse, Landgrave Philipp received annual revenues of 16,500 guilders in 1532 from monastery lands and 25,000 guilders in 1565, equivalent to one-seventh of total state revenues and around 1,000 person-years of skilled wages. Overall, 40% of monastic wealth in Hesse went to the ruler – not to religious, educational, or social welfare purposes. In East Frisia, Count Enno II converted the monastery in Norden into a summer residence for himself and converted the monastery at Ihlow into a residence for his brother. In Brandenburg, monasteries were allowed to keep their privileges following the adoption of Protestantism in exchange for a payment of 300,000 guilders. Protestant theologians provided the legal justification for these transfers of wealth – this is consistent with our framework, which views these transfers as outcomes of bargains between secular and religious elites.

Empirical evidence on resource reallocation

The massive shift in political power and resources after 1517 should have had broader consequences for the allocation of resources across the economy:

- We expect a reduction in labour demand in the religious sector of the economy, and increased demand in the secular sector – particularly from enriched secular lords.

- Forward-looking students would have shifted their educational investments away from theology, which paid off specifically in the religious sector, and towards more general subjects.

- Major new construction events – embodying physical, financial, and human capital, as well as land – would have shifted toward structures reflecting the interests of secular lords (palaces and administrative buildings).

To examine whether resources shifted in the direction suggested by our conceptual framework – away from church uses and toward secular uses, especially those favoured by empowered and enriched territorial lords – we collect a wide array of micro data shedding light on the German economy of the 16th century.

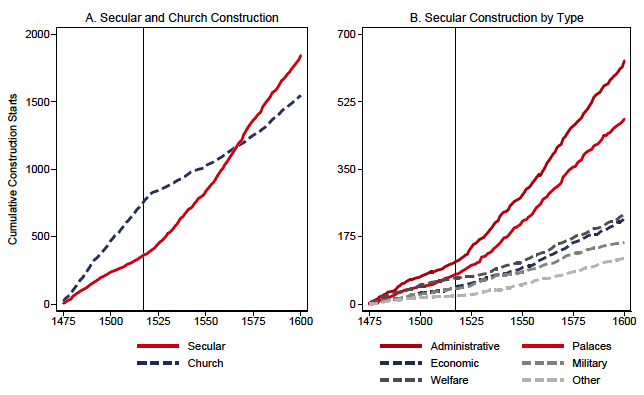

First, we analyse major construction events in towns and cities across Germany. As we show in Figure 1, during the Reformation new construction events shifted from primarily religious purposes toward secular ones. We see a striking pivot from church-sector construction to secular-sector construction precisely at the time of the Reformation, as shown in Panel A. Consistent with our conceptual framework, within the category of secular construction, there was a sharp pivot precisely toward the uses favoured by empowered secular lords – the construction of palaces and administrative buildings increases after 1517, as shown in Panel B.

Figure 1

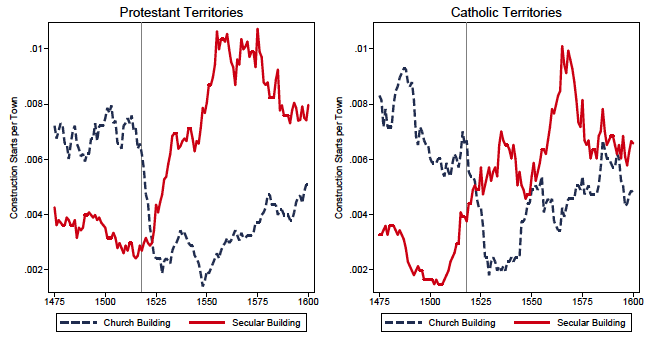

These changes were particularly evident in the Protestant territories of the Empire. Figure 2 shows that both Catholic and Protestant regions witnessed a decline in church construction following 1517. However, only in Protestant regions (left panel) was there a sustained increase in secular construction, leading to a permanent gap between church and secular construction rates. In our analysis, we also show that the additional secular construction in Protestant territories was, for the most part, composed of palaces and administrative buildings.

Figure 2

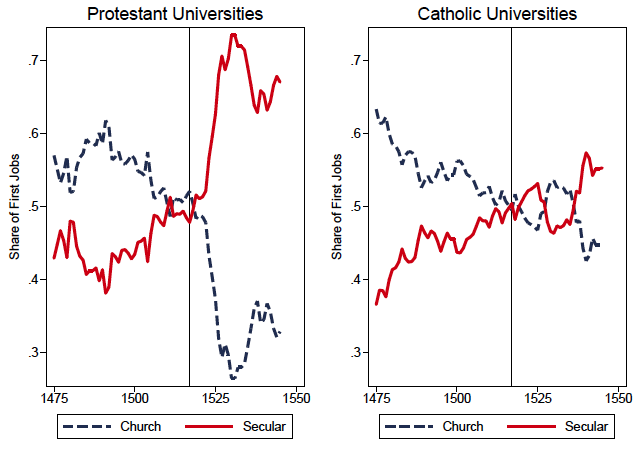

Turning to occupational choices, in Figure 3 we show careers of recipients of academic degrees from German universities through the year 1550. Prior to 1517, graduates of eventually Protestant universities sorted into religious and secular occupations at similar rates to graduates from universities that would remain Catholic. After 1517, however, there is a sharp shift towards ‘secular’ occupations among Protestant university graduates, and no such shift among Catholic university graduates. The Protestant shift toward secular occupations was concentrated in the administrative sector that reflected the interests of secular rulers.

Figure 3

The shift in occupational sorting across sectors is reflected in human capital investments as well. Students at Protestant universities shifted sharply away from theology study, towards other degrees such as law and arts, after the Reformation.

Implications for social science and beyond

Our findings shed new light on some of the most important debates in the social sciences. We provide evidence that the Reformation indeed marked a decisive economic break from the past, playing a causal role in the transformation of Europe’s economy. While this may appear supportive of the ‘Weber Hypothesis’, we provide a mechanism for long-run effects of the Reformation very different from the cultural channel emphasised by Weber (1904/05). The finely grained data we collect enable us to document that Protestant and Catholic regions and universities were not on different trajectories before the Reformation. However, our analysis indicates that the initial separation between religious and secular authority in Europe provided a fundamental precondition that shaped how the introduction of religious competition impacted the economy.

Five hundred years on from Martin Luther's audacious act, our findings confirm that the Reformation transformed not only Western Europe's religious landscape, but also its politics and economy. Thus, social scientists have been right to point to the Reformation as a crucial turning point in European and world history. Significantly, our findings indicate that some of the Reformation's most important consequences were unintended, and have not been fully documented before – the results of interactions among religion, politics, and economics, which produced a secular Europe from its most famous religious movement.

References

Becker, S O and L Woessmann (2009), “Was Weber Wrong? A Human Capital Theory of Protestant Economic History,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 124(2): 531–596.

Cantoni, D (2015), “The Economic Effects of the Protestant Reformation: Testing the Weber Hypothesis in the German Lands,” Journal of the European Economic Association 13(4): 561–598.

Cantoni, D, J Dittmar, and N Yuchtman (2017), “Religious Competition and Reallocation: The Political Economy of Secularization in the Protestant Reformation,” NBER Working Paper No. 23934.

Chaney, E (2013), “Revolt on the Nile: Economic shocks, religion, and political power,” Econometrica 81(5): 2033–2053.

Ekelund, R B, R F Hébert, and R D Tollison (2006), The Marketplace of Christianity, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

North, D C, J J Wallis, and B R Weingast (2009), Violence and Social Orders: A Conceptual Framework for Interpreting Recorded Human History, Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Rubin, J (2017), Rulers, Religion, and Riches: Why the West Got Rich and the Middle East Did Not, Cambridge, UK and New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Schwinges, R C and C Hesse (2015), “Repertorium Academicum Germanicum,” http://www.rag-online.org.

Tawney, R H (1926), Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, London: J. Murray.

Weber, M (1904/05), “Die protestantische Ethik und der ‘Geist’ des Kapitalismus,” Archiv fur Sozialwissenschaften und Sozialpolitik, 20-21, 17–84; 1–110 (English translation published in 1930 as The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism by Allen & Unwin).

Weber, M (1978), Economy and society: An outline of interpretive sociology, Vol. 1, University of California Press.