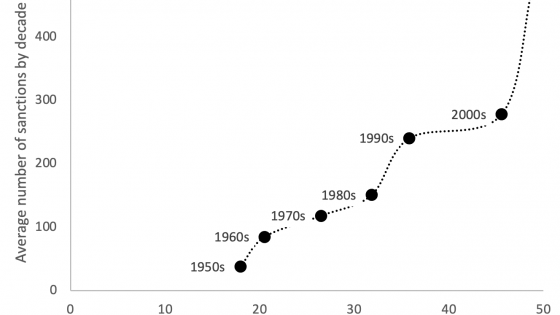

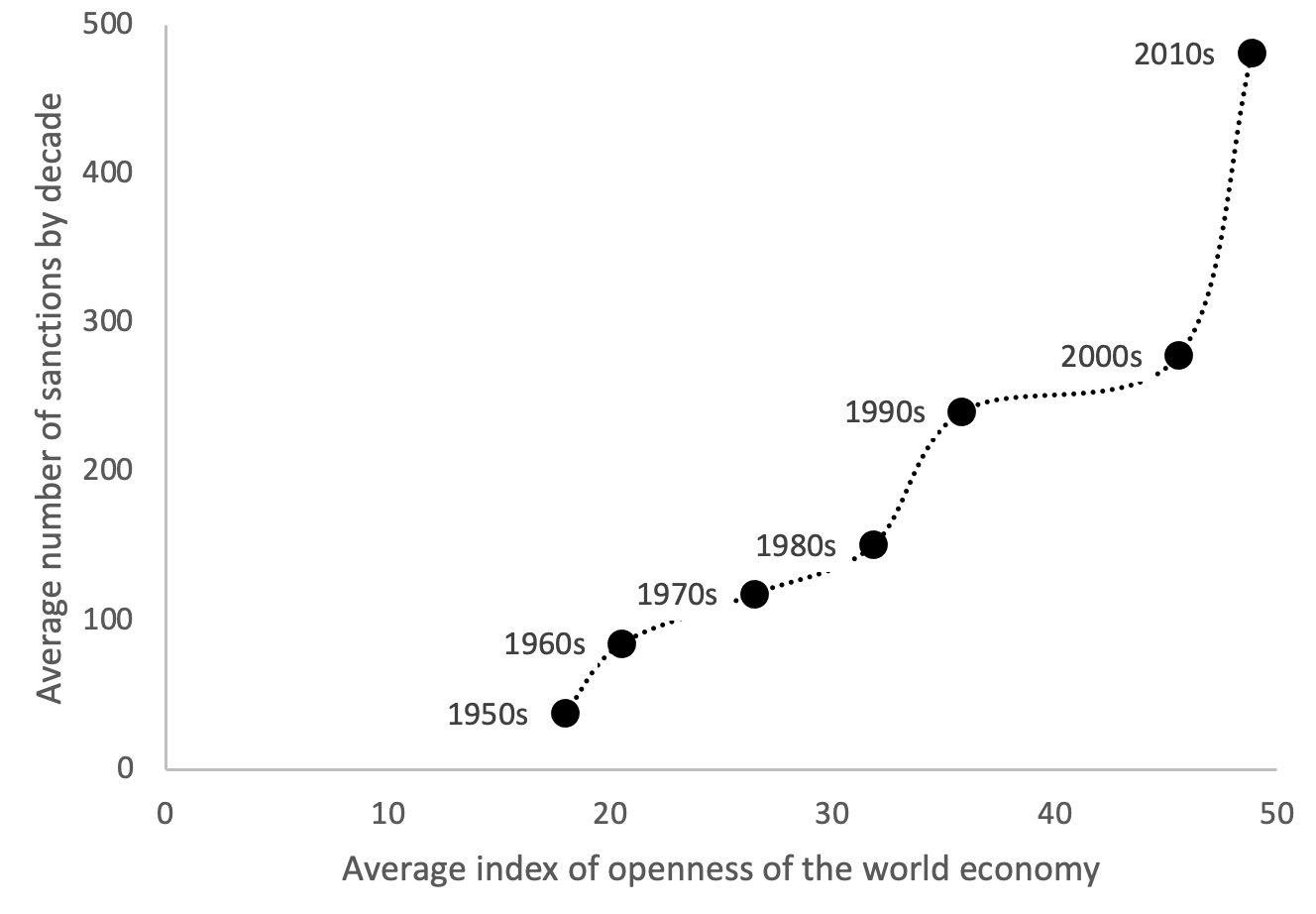

Economic sanctions have become a diplomatic tool of preference over the last decade. This is more than a casual observation. Thanks to new data sets such as the Global Sanctions Database (Felbermayr et al. 2021, Kirilakha et al. 2021), we can measure the second wave of sanction implementation in the 2010s. Figure 1 illustrates that the recent sanction wave, with an increase of 73%, outstrips the first sanction wave of the 1990s (a 59% increase).

The increase will be puzzling as the conventional wisdom, among economists at least, is that economic sanctions, for all their posturing, won’t achieve very much (van Bergeijk 2012). Indeed, a recent meta-analysis (Demena et al. 2021) uncovers significant publication bias in the empirical literature that developed since 1985: the impact of trade, pre-sanctions relations, and sanction duration on the political outcome of sanction cases cannot be assessed. The econometric evidence for the effectivity of sanctions is therefore much weaker than often thought. Still the instrument has been increasingly used in every decade since WWII. So, what happened and why?

Figure 1 Sanction impositions and openness of the world economy (averages by decade, 1950-2019)

Source: van Bergeijk (2021).

The first sanction decade (1990s)

Could history perhaps help us to understand the increase in the 2010s? After all, a similar increase in the use of economic sanctions can also be observed in the 1990s. What can explain that upsurge?

The year 1990 marked the end of the Cold War, the sanctions in response to the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, and the start of a significant increase in the speed of globalisation (which can be recognised in the rightward shift of the curve in Figure 1). These three events were at the time readily identified as factors behind the increase in the use of economic sanctions (van Bergeijk 1995). The three drivers of the increase are, of course, to a larger extent interrelated. Indeed, the end of the superpower conflict enabled the UN sanctions to be implemented quickly and comprehensively: the severe, wide-ranging, and almost watertight sanctions against Iraq in 1990 were implemented in four days, and for the first time in history traditionally neutral Switzerland participated. This experience was the basis for a UN sanction wave (Biersteker and Hudáková 2021). Globalisation, stimulated by the breakdown of communism, opened up many economies that previously could hardly be hurt by economic sanctions. All in all, the historical context seemed to a large extent to be conducive to the increase in sanction imposition in the 1990s. Importantly, the 1990s also saw a strong increase in targeted sanctions, although that development waned at the turn of the millennium (Morgan et al. 2021).

The second sanction decade is a different animal

Economic sanctions as a policy tool proliferated in the 2010s (Halcoussis et al. 2021). However, the apparent increase in sanction use to an average of almost five hundred imposed sanctions per year is, from a geo-economic perspective, more difficult to understand. First, the geopolitical context of the 2010s is actually the mirror image of the détente and perestroika that led to the demolishment of the Berlin Wall and the Iron Curtain. Currently a Cold Trade War – if not a New Cold War– is emerging. US–Chinese rivalry is one important driver. Other determinants are the sanctions and counter sanctions between Russia, the EU, and the US (Bělín and Hanousek 2019, 2021). Second, the other major cases of the 2010s, the sanctions against Iran (Dizaji and van Bergeijk, 2013) and North Korea (Han 2021), were protracted and characterised by unstable sender coalitions. Third, the financial crisis in 2008/9 was a turning point for globalisation, with global openness decreasing even before the trade wars initiated by President Trump, the exit of the UK from the EU, and the trade crunch of the COVID-19 pandemic (Meijerink et al. 2020).

So, why did the numbers on the ‘market’ for economic sanctions increase in the 2010s? On the ‘demand side’, the increase appears to have been driven by the combination of a reduced role of armed conflict resolution and the growing importance of strategic trade policy considerations, (Hufbauer and Jung 2021). On the ‘supply side’, the enhanced efficiency and the reduction of collateral damage may have helped to increase the number of sanctions over time. The former decreases the costs for the sender; the latter reduces unintended costs for the target’s population.1 In the same vein, the process of implementation and compliance regarding US sanctions has been improved thanks to major investments in staffing, procedures, communication, and monitoring (Early 2021). Also, new sanction modes were developed extending the sanction domain into tourism (Hall and Seyfi 2021), trade preferences (Portela 2021), and the international payments system (Dizaji 2021).

In addition to these underlying drivers that work at the national case level, the perceived need to support global public goods by imposing costs on free-riding behaviour is a relatively new element. This issue may be particularly relevant in the context of 2020 and 2021: the COVID-19 pandemic, global warming, and the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction are global ‘public bads’. Their solution requires strengthening of global public goods management. However, this collective action is complicated by fragmentation of the world economy in the wake of deglobalisation and the challenge to US hegemony caused by the rise of China. Against this background economic sanctions may be seen as a vital instrument to fight global bads.

Conclusion: The outlook

The increase in imposed sanctions is coinciding with a deglobalisation phase. This contrasts with the upswing of globalisation that characterised the 1990s. Indeed, the exponential increase in sanction impositions creates trade uncertainty and this is a strong incentive for firms and countries to reduce international specialisation. It is tempting to conclude that the rise in the application of economic sanctions has reduced the extent of international worldwide exchange, but it is of course equally possible that economic sanctions are a symptom of the underlying disease of deglobalisation that started around 2008–09. If so, this may offer a structural explanation for the stark increase of sanction implementation in the 2010s and suggests that the increasing use of economic sanctions will be sustained in the foreseeable future.

References

Bělín, M and J Hanousek (2019), “Making sanctions bite: The EU–Russian sanctions of 2014”, VoxEU.org, 29 April.

Bělín, M and J Hanousek (2021), “Imposing sanctions versus posing in sanctioners’ clothes: the EU sanctions against Russia and the Russian counter-sanctions”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 249-263.

Biersteker, T and Z Hudáková (2021), “UN targeted sanctions: Historical development and current challenges”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 108-125.

Demena, B A, A S Reta, G Benalcazar Jativa, P B Kimararungu and P A G van Bergeijk (2021), “Publication bias of economic sanction research: a meta-analysis of the impact of trade linkage, duration and prior relations on sanctions success”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 126-151.

Dizaji, S F and P A G van Bergeijk (2013), “Could Iranian sanctions work? ‘yes’ and ‘no’, but not ‘perhaps’”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

Dizaji, S F (2021), “The impact of sanctions on the banking system: new evidence from Iran”, in Peter A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 330-350.

Early, B R (2021), “Making sanctions work: promoting compliance, punishing violations, and Discouraging Sanctions Busting”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 167-186.

Felbermayr, G, A Kirilakha, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y Yotov (2021), “The ‘Global Sanctions Data Base’”, VoxEU.org, 18 May.

Halcoussis, D, W H Kaempfer and A D Lowenberg (2021), “The public choice approach to international sanctions: retrospect and prospect”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 152-166.

Hall, C M and S Seyfi (2021), “Tourism and sanctions”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 351-368.

Han, B (2021), “Secondary sanctions mechanism revisited: the case of US sanctions against North Korea”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 223-237.

Hufbauer, G C. and E Jung (2021), “Economic Sanctions in the 21st Century”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp 26-43.

Kirilakha, A, G Felbermayr, C Syropoulos, E Yalcin and Y V Yotov (2021), “The Global Sanctions Data Base: An Update that Includes the Years of the Trump Presidency”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 62 – 107.

Meijerink, G, B Hendriks and P A G van Bergeijk (2020), “Covid-19 and world merchandise trade: Unexpected resilience”, VoxEU.org, 2 October.

Morgan, T C, N Bapat, and Y Kobayashi (2021), “The Threat and Imposition of Economic Sanctions data project: a retrospective”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 44-61.

Portela, C (2021), “Trade preference suspensions as economic sanctions”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar, pp. 264-279.

van Bergeijk, P A G (1995), “The Impact of Economic Sanctions in the 1990s”, The World Economy 18(3): 443-455.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2012), “Failure and success of economic sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 27 March.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2019a), “Brexit delay will not postpone deglobalisation”, VoxEU.org, 18 March.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2019b), Deglobalization 2.0 Trade and openness during the Great Depression and the Great Recession, Edward Elgar.

van Bergeijk, P A G (2021), “Introduction”, in P A G van Bergeijk (ed.), Research Handbook on Economic Sanctions, Edward Elgar.

Endnotes

1 See Biersteker and Hudáková (2021) for a discussion of the sanctions reform processes of the UN, US and EU sanctions in the 2000s, when sanction practitioners were on the steep learning curve.