People are not robots; we need sleep to recover energy. Sleeping is the activity that people spend most time on in a normal week. Lack of sleep contributes to the desynchronisation of circadian rhythms and weakens the immune system and cognitive activity in addition to physical and mental health (Nagai et al. 2010). Lack of sleep is associated with unhealthy behaviours related to a modern lifestyle, the presence of psychosocial stress, an unbalanced diet, and limited physical activity.

Although sleeping enough is essential for optimal physical and psychological wellbeing, we do not always get enough sleep to feel rested. An individual’s quality of sleep is not completely under an individual’s control. It is a reflection of our worries and experiences in our professional and personal lives, including exposure to digital temptations, commuting time, financial worries, and work stress; sugary diets and mental health can also influence sleep.

Lack of sleep is so widespread that when people are asked what they would do with an unexpected weekly time windfall, the most common response is to sleep more (National Sleep Foundation 2020). Luckily, sleep patterns differ between weekdays and weekends, as unstructured time allows us to meet our sleep needs. Some of us sleep more on weekends, while others take daytime naps to compensate for this chronic lack of sleep. All of this explains the increase in sleep time dispersion over recent decades in the US (Hamermesh and Pfann 2022).

However, sleep is not factored in classic textbook microeconomic models, which typically refer to the trade-off between allocating time to leisure or work. Sleeping time is assumed to be constant. But today, we know that sleep is important as another time constraint in making time allocations, and it exerts effects on our physical and mental health.

Social and economic drivers of sleep

Sleep quality is affected by changes in exposure to light, noise or the use of communication technologies (mobile devices), and access to the Internet or television. For example, the intensity of light in homes has an environmental influence on sleep quality, since natural melatonin is influenced by light exposure. Likewise, the time spent using technologies can compete with the time individuals would spend sleeping without them, and ‘digital temptations’ not only reduce sleep time but increase exposure to blue light technologies just before going to sleep (Billari 2018). Finally, those of us who are parents will have experienced first-hand how the quality of sleep deteriorates when there are children in the home.

Any economist who has read Gary Becker’s theory of time allocation would surely point out the opportunity cost of sleep, that is, the utility loss in terms of leisure and work derived from allocating time to other activities. Higher pay and responsibility, or an intense night-time social life, can take their toll in terms of lack of sleep. For example, a classic estimate suggests that a 1-hour increase in work time is associated with a 13-minute reduction in sleep (Biddle and Hamermesh 1990).

Of course, the cost of sleep can vary over people’s life cycles and even across seasons and time zones. What we do know is that this opportunity cost of sleep is exogenously influenced by the economic cycle, and some studies estimate that sleep duration is countercyclical: you sleep better when economic activity slows down, and sleep duration decreases when economic activity recovers (Costa-Font 2022).

Sleep and productivity

Sleep not only affects wellbeing through the direct utility derived from its consumption but also through the greater income and productivity from feeling rested, which affects work motivation and cognitive functions. One way to study the effect of exogenous changes on sleep is to use changes in time zone variation to sunset times.

One such study using cross-sectional time-use data from the US estimates that a one hour increase in weekly sleep time generates an increase in earnings by 1.1% in the short run and 5% in the long run (Gibson and Shrader 2018). These results are economically relevant: they suggest that an extra hour of sleep per week raises earnings by roughly half as much as an additional year of formal education. But the study does not account for the fact that sleep is different for each person. Accounting for individual differences would require data that accounts for individual fixed effects. Further, estimates might be different in European labour markets, which operate differently due to the greater presence of union negotiations and where hourly pay is less common.

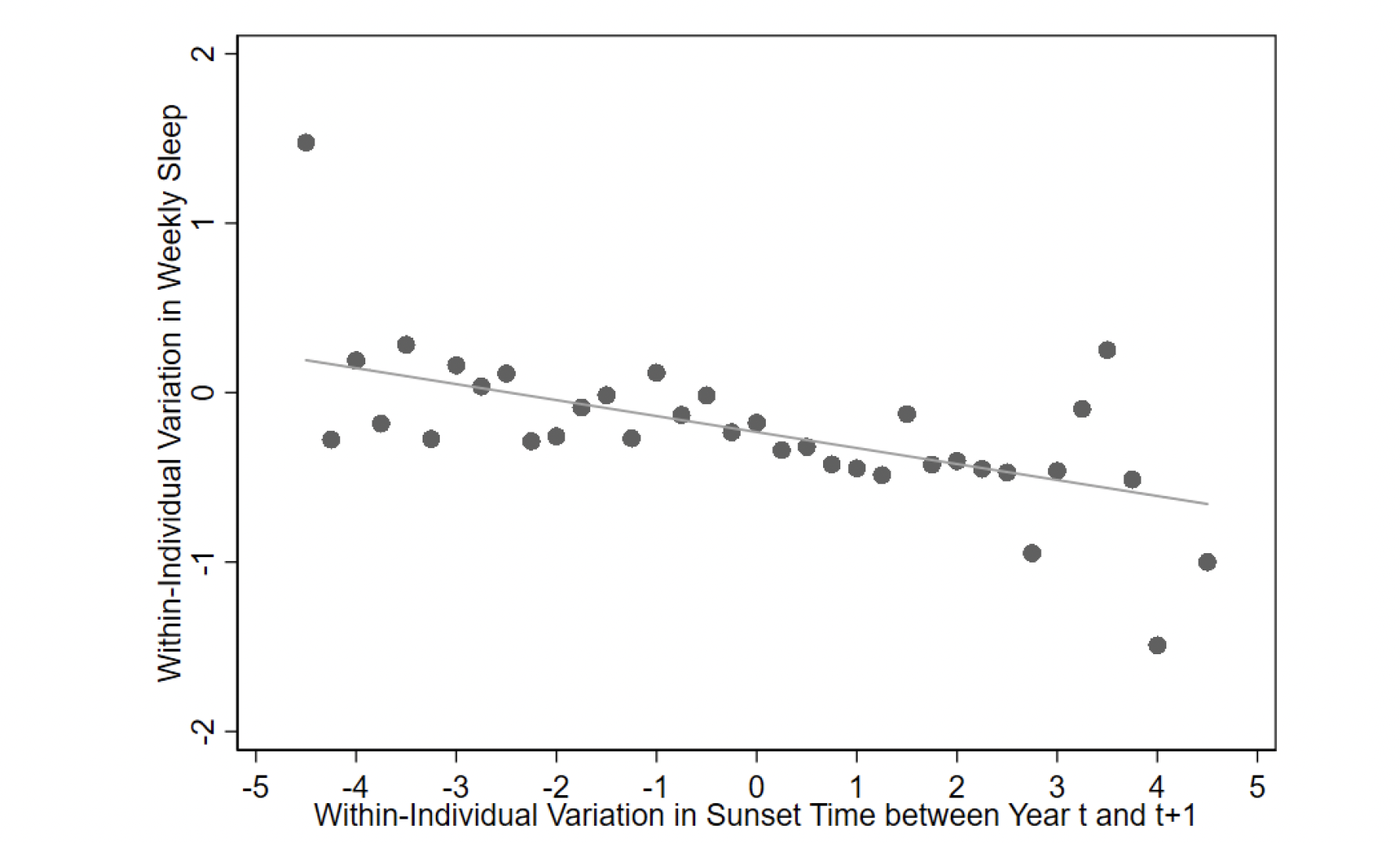

In our study (Costa-Font et al. 2024), we draw on panel data from Germany to estimate – analogously to the American study – how the amount of weekly sleep influences employment, productivity, and income of individuals. As displayed in Figure 1, we exploit as a natural experiment evidence that suggests that, on average, one hour of sun exposure reduces sleep hours by between 5 and 7 minutes, depending on where an individual lives in Germany (Costa-Font et al. 2024). We estimate that each additional hour of sleep per week increases the probability of employment by 1.6 percentage points and weekly earnings by 3.4%.

Figure 1 Sleep and light exposure

These estimates are also comparable to those of another work with British data (Costa-Font and Fleche 2017), where we used the variations in child sleep interruptions over time as an instrument for changes in mothers’ (and fathers’) sleep duration, to estimate the effect of sleep on the economic performance of mothers (Costa-Font and Fleche 2020). We documented that increasing the average duration of a mother’s night’s sleep by half an hour increases her participation in the labour market by 2.5 percentage points, her working hours by 8.3%, and her family income by 3.1%, although their job satisfaction only increases very slightly. We observe that these effects depend on the influence of maternal sleep on selection into full-time versus part-time work. However, we found that increased work schedule flexibility among more experienced mothers partially mitigates the negative effects of sleep deprivation.

Economic effects and incentives to sleep

Some research has quantified the overall effects of sleep on the economy. The monetary costs of sleep deprivation on the economy are estimated at 1.9–2.9% of GDP in the US, 1.4–1.8% in the UK, 1.0–1.6% in Germany, and 0.8–1.6% in Canada (Hafner et al. 2017).

Given the effect that sleep has on work outcomes and health, some organisations have considered designing incentives for sleep. For example, Aetna, a private health insurance company, offers $25 for every 20 nights that people sleep 7 hours or more, with a limit of $500 a year, which is monitored by electrical devices (Hallett 2016). This effect adds to other evidence suggesting that subsidising digital information devices to track sleep can incentivise the time allocated to sleep. In fact, evidence from a randomised control trial suggests that a subsidy to employees to purchase a wearable bracelet significantly improves sleep and exercise (Handel and Kolstad 2017).

However, one possible criticism of traditional economic approaches to sleep is that it is unclear to what extent individuals are aware of its effects on their economic activity, which limits the role of traditional economic incentives. This seems a fertile field to test behavioural incentives, since many of the decisions about sleep are automatic, forged by routines and not by conscious decisions, which opens the possibility of making multiple adjustments in the sleep decision-making architecture.

What are the policy implications?

Public interventions can make these economic effects of lack of sleep more salient to individuals. For example, it is possible to redesign television programme schedules or work hours, as well as regulate work expectations about answering emails and access to screens at night in general. Another issue that we could revisit via policy interventions is the so-called ‘cultural or social reference points’.

Lack of sleep generates what we call internalities in behavioural economics. That is, it entails negative consequences on our future wellbeing (future selves). Since people are subject to ‘present bias’, we fall to the temptation of delaying bedtime for the immediate gains of watching our favourite television series or having interesting conversations, ignoring tomorrow’s losses in productivity and motivation. These behavioural biases point to the need for behavioural interventions (‘nudges’), as simple as an alarm when it’s time to go to sleep.

References

Biddle, J E, and D S Hamermesh (1990), “Sleep and the allocation of time”, Journal of Political Economy 98(5): 922–43.

Billari, F C, O Giuntella, and L Stella (2018), “Broadband internet, digital temptations, and sleep”, Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 153: 58–76.

Costa-Font, J (2022), “Incentivizing sleep?”, IZA World of Labor.

Costa-Font, J, and S Fleche (2017), “Sleep deprivation and employment”, VoxEU.org, 1 May.

Costa-Font, J, and S Fleche (2020), “Child sleep and mother labour market outcomes”, Journal of Health Economics 69: 102258.

Costa-Font, J, S Fleche, and R Pagan (2024), “The labour market returns to sleep”, Journal of Health Economics 93: 102840.

Gibson, M, and J Shrader (2018), “Time use and labor productivity: The returns to sleep”, Review of Economics and Statistics 100(5): 783–98.

Hallett, R (2016), “Why one company is paying its staff to sleep”, World Economic Forum, 12 July.

Handel, B, and J Kolstad (2017), “Wearable technologies and health behaviors: New data and new methods to understand population health”, American Economic Review 107(5): 481–85.

Hamermesh, D S, and G A Pfann (2022), “The variability and volatility of sleep: An ARCHetypal behavior”, Economics and Human Biology 47: 101175.

Nagai, M, S Hoshide, and K Kario (2010), “Sleep duration as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease – a review of the recent literature”, Current Cardiology Reviews 6(1): 54–61.

National Sleep Foundation (2020), “Sleep in America poll: Americans feel sleepy 3 days a week, with impacts on activities, mood and acuity”.