The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) significantly steps up the US efforts in the fight against climate change and aims to increase the US ability to attract key green technologies. To these ends, it foresees significant financial incentives (i.e. tax credits for the purchase of electric vehicles (EVs) and investments in renewable energy equipment) conditional on specific domestic content requirements.

The IRA substantially revised the US law on tax credits for EVs; to qualify for it, final assembly must take place in North America and a significant proportion of the components and minerals in the battery must be manufactured or assembled in North America (components) or in a country with which the US holds a free trade agreement (minerals).

For investments in renewable energy development the IRA implements an additional tax credit if a certain proportion of the components are produced in North America. By discriminating against products manufactured outside the USMCA (US, Mexico, and Canada trade Agreement), the IRA provisions could adversely affect third countries via trade and relocation channels.

Modelling the spillover effects

We quantify the potential economic effects of the Inflation Reduction Act using the Baqaee and Farhi (2023) model for a sample of 41 countries (or country groups) and 30 sectors.

This model allows us to estimate the non-linear effects of higher trade barriers and to consider the endogenous reaction of producers and consumers in an inter-connected world economy.

The focus of the analysis is on two IRA provisions: the tax credit for the purchase of EVs and the bonus for investment in renewable energy equipment, and their related content requirements. These measures are modelled as a trade cost shock that decreases the price of EVs and renewable energy equipment for US consumers if these are bought from USMCA producers.

In addition, a second set of shocks simulates the impact of domestic content requirements for intermediate inputs used by USMCA producers of EVs, batteries, and renewable energy equipment. This is simulated by imposing an iceberg trade cost shock to imports from suppliers outside the USMCA of batteries, critical minerals, power components, steel, and iron.

In order to reflect the growing significance of the green sectors, we rescale the magnitude of the abovementioned shocks using the International Energy Agency (IEA) projections for 2030.

In addition, as the speed of the green transition remains uncertain, we use three different sets of assumptions from the IEA namely: (1) the ‘conservative’ scenario, based on stated policies as of 2022, (2) the ‘accelerated’ scenario, which also includes announced policies and is more optimistic concerning the speed of the green transition, and (3) the ‘net zero’ scenario, based on policies required to abide by the goal of net-zero carbon emissions by 2050 and entails more radical policy measures.

Furthermore, standard trade elasticities (i.e. measuring the ease of substituting suppliers across countries), might not adequately reflect the emerging nature of the green sectors given that, compared to more mature production lines, producers may find it easier to divert new investments abroad. Therefore, for the accelerated and net zero scenarios we apply higher trade elasticities than estimated in the literature.

Likewise, as it might be hard to find alternative suppliers for rare critical minerals and high-end technologies, the simulations in the accelerated and net zero scenarios assume lower than standard elasticities of substitution across products (measuring the ease of substituting across different inputs for production).

Finally, a main objective of the IRA is to make the US the preferred location of new investments, generating technology-investment driven productivity growth. This would increase productivity in the US while having the opposite effect in the rest of the world, widening inter alia the productivity gap between EU and US. We account for such a productivity impact of green investments by adding an exogenous total factor productivity (TFP) shock to the simulations.

We find that these productivity gains would increase the comparative advantage of US producers relative to the rest of the world, thus magnifying the relocation and trade effects. The quantification of trade and relocation effects in the remainder of this column refer to long run effects with a time horizon of 2030.

A quantification of trade and relocation effects

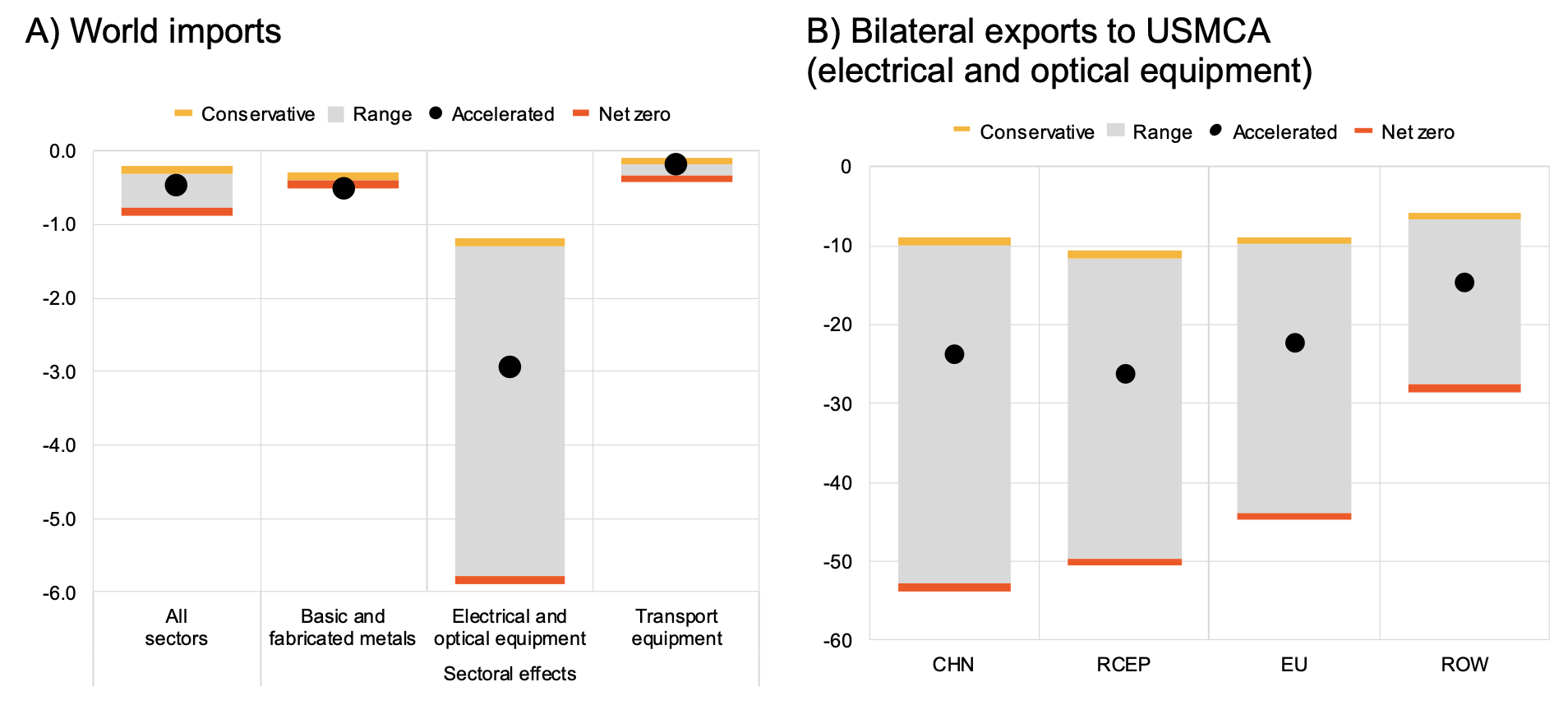

Losses of global trade are limited, ranging from 0.2% (conservative) to 0.9% (net zero) (Figure 1, Panel A). This is explained by the fact that the trade shock originates from one country only (the US), which does not affect its largest trade partners (Mexico and Canada) and is limited to only three sectors. Moreover, the IRA induces a re-allocation of trade flows rather than a destruction thereof. On the other hand, sectoral losses can be substantial in sectors targeted by the IRA, notably in the electrical and optical equipment sector where global trade losses reach 6% in the net zero scenario (Figure 1, Panel A).

The rest of this column focuses on the effects in this sector.

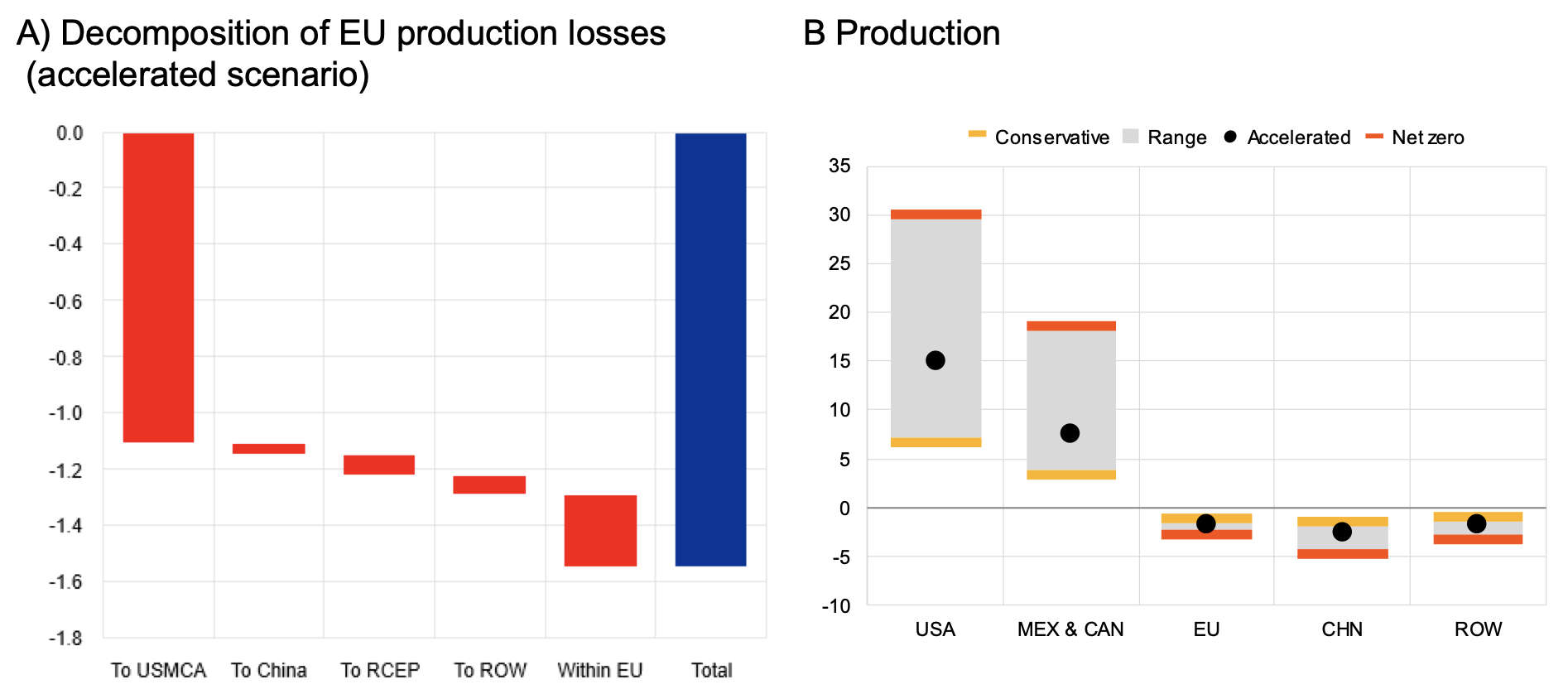

US trade partners are concerned not only by the prospective loss of access to the US market, but also by reduced possibilities to divert their production to other destinations. China would lose between 10% (conservative) and 50% (net zero) of its exports to USMCA in electrical and optical equipment, and the EU would lose between 10% and 45% (Figure 1, Panel B). However, a compounding issue would be the absence of trade diversion. As shown in Figure 2 (Panel A) for the EU, while production losses are foremost due to lower exports to the USMCA given the IRA-induced trade barriers, exports to other countries are also lower– reflecting second-round effects, mostly in the form of excess supply in the sector and lower demand for upstream products.

Figure 1 Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on trade (percentage change from steady state)

Sources: Baqaee and Farhi (2023), ADB IO table, ECB staff calculations

Notes: Non-linear impact simulated through 25 iterations of the log-linearised model. Electric vehicles (EV) are a sub-sector of ‘transport equipment’, EV batteries and renewable energy equipment of ‘electrical and optical equipment’, and processed rare Earth minerals of ‘basic and fabricated metals’. USMCA = US, Mexico, and Canada (trade) Agreement; RCEP = Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade agreement among 15 Asia-Pacific countries; ROW = rest of the world. RCEP does not include China.

Figure 2 Impact of the Inflation Reduction Act on production (electrical and optical equipment, percentage and percentage points change from steady state)

Sources: Baqaee and Farhi (2023), ADB IO table, ECB staff calculations

Notes: Non-linear impact simulated through 25 iterations of the log-linearised model. USMCA = US, Mexico, and Canada (trade) Agreement; RCEP = Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade agreement among 15 Asia-Pacific countries; ROW = rest of the world. RCEP does not include China.

The IRA entails large relocation of production capacities towards the US. Relocation effects are measured by production changes shown in Figure 2 (Panel B). The US would gain from positive relocation effects, increasing production by 6% to 30% in electrical and optical equipment. Relocation effects would also be positive for Mexico and Canada (3% to 19%); in contrast, the IRA entails production losses for the EU (between -0.5% and -3%) and China (between -1% and -5%). In the rest of the world, larger production losses are faced by countries with higher exposure to the USMCA such as Malaysia and Vietnam (up to -18% and -13% production losses respectively in the net zero scenario).

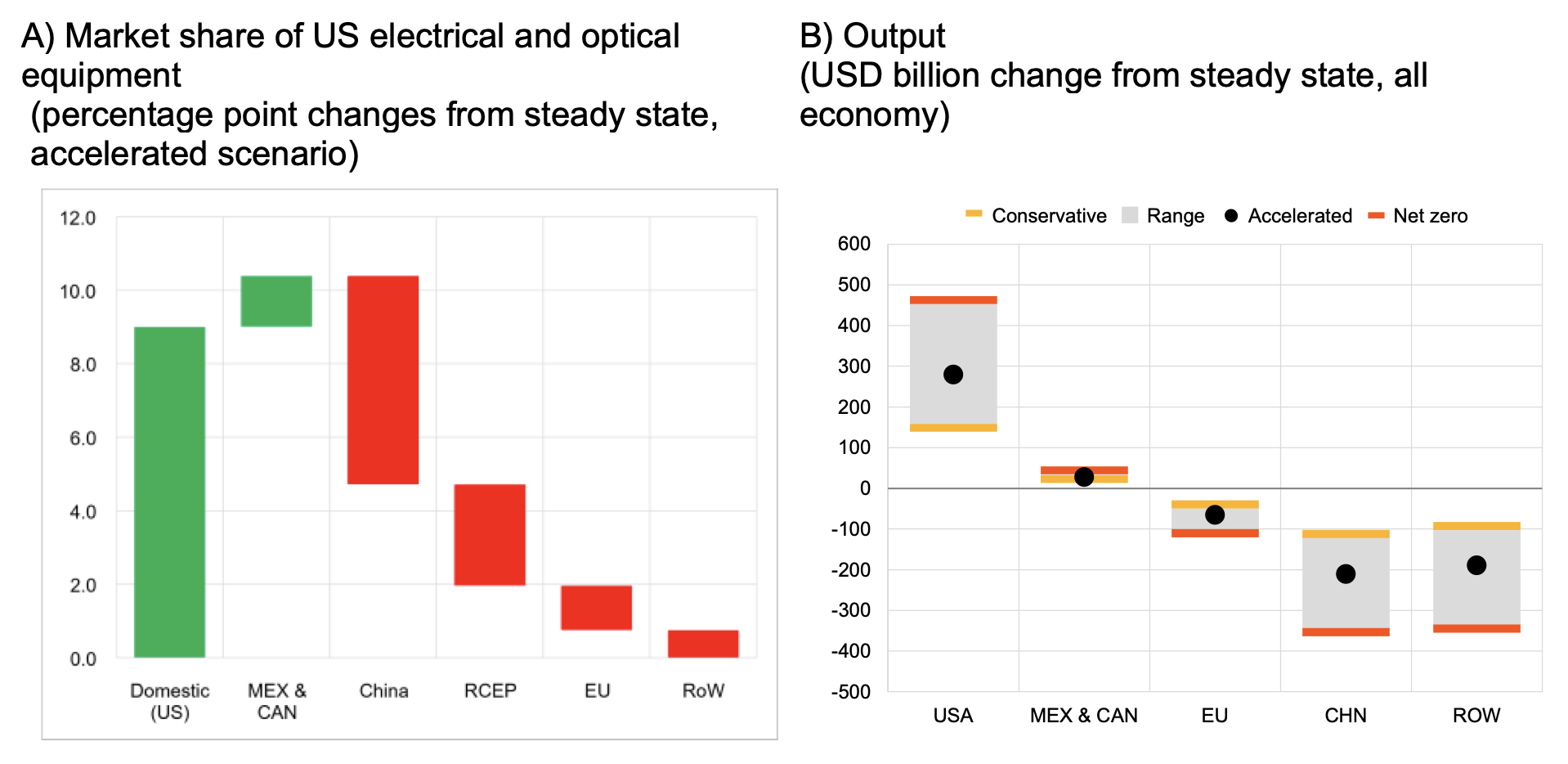

These relocation effects translate into changes of market share.

Focusing on the US domestic demand of electrical and optical equipment, Figure 3 (Panel A) shows that that US producers gain nine percentage points in market share, mostly at the expenses of China (-6 percentage points).

While the rest of the world loses, the IRA would benefit the US through additional output and lower strategic dependence vis-à-vis China. Reported in nominal terms, the IRA would entail by 2030 the relocation to the US of $280 billion worth of annual output across all sectors (accelerated scenario) mainly at the expenses of China (-$210 billion) and, to a smaller extent, the EU (-$70 billion).

While these represent a relatively small share of total output (i.e. a 0.7% increase in US output and a -0.2% and -0.4% decrease in EU and Chinese output respectively) sectoral effects are more sizeable (+15% for electric and optimal equipment production in the US, and -1.6% and -2.4% in the EU and China respectively). Output gains/losses would be larger in the net zero scenario for the US and China respectively (Figure 3, Panel B).

At the global level, summing across all effects (positive in USMCA, negative elsewhere), the IRA translates into net annual output losses concentrated mostly in the green sectors, thus suggesting that the IRA could slow the green transition at global level.

Figure 3 ‘Winners’ and ‘losers’ of the Inflation Reduction Act

Sources: Baqaee and Farhi (2023), ADB IO table, ECB staff calculations

Notes: Non-linear impact simulated through 25 iterations of the log-linearised model. Panel a) refers to the accelerated scenario; red and green bars indicate respectively negative and positive impacts. USMCA = US, Mexico, and Canada (trade) Agreement; RCEP = Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership, a trade agreement among 15 Asia-Pacific countries; ROW = rest of the world. RCEP does not include China. Panel b) states the US dollar change (in billions) from steady state expressed in 2021 levels.

What’s next?

The stylised analysis presented in this column shows that policies aimed at boosting the green transition, if coupled with measures erecting barriers against trade, would distort sectoral trade flows and lead to a reallocation of production in the green sectors mainly in response to financial incentives and not necessarily according to a country’s comparative advantage. Should the main US trading partners take retaliatory measures as part of their response to the IRA, this would likely cause further harm, as increased domestic production would come at the cost of a slower green transition including by hindering the international diffusion of knowledge in green technologies. Therefore, from a purely economic perspective, the first best response to climate change remains international cooperation; after all climate change is a global challenge that requires global solutions.

At the same time, it should be recognised that the re-evaluation of domestic security priorities is an important element in shaping domestic policies. The green transition, and the technological progress it entails, can usher an industrial and technological revolution with far reaching economic implications in terms of consumption possibilities, job creation, technological progress, and new strategic dependencies. Therefore, countries have an incentive to attract investments that will give them a competitive edge in the key sectors of the future (Terzi 2022). In light of these considerations, the estimated economic effects presented in this column likely represent a lower bound for both winners and losers.

Authors’ note: This column reflects the opinions of the authors and not necessarily those of the European Central Bank.

References

Atalay, E (2017), “How Important Are Sectoral Shocks?”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 9(4): 254–280.

Attinasi, M G, L Boeckelmann and B Meunier (2023), “Friend-shoring global value chains: a model-based analysis”, Economic Bulletin Box 2, European Central Bank.

Bachmann, R, D Baqaee, C Bayer, M Kuhn, A Löschel, B Moll, A Peichl, K Pittel and M Schularick (2022), “What if? The economic effects for Germany of a stop of energy imports from Russia”, ECONtribute Policy Brief No 28/2022.

Baqaee, D and E Farhi (2023), “Networks, Barriers, and Trade”, Econometrica, forthcoming

Cai, J, N Li and A M Santacreu (2022), “Knowledge Diffusion, Trade, and Innovation across Countries and Sectors”, American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 14(1): 104–145.

Costinot, A and A Rodriguez-Clare (2014), “Trade theory with numbers: quantifying the consequences of globalization”, Handbook of International Economics 4, 197.

Goes, C and E Bekkers (2022), “The impact of geopolitical conflicts on trade, growth, and innovation”, Staff Working Paper No. ERSD-2022-9, World Trade Organization.

Terzi, A (2022), “A green industrial revolution is coming”, VoxEU.org, 28 June