Portugal is a small country (albeit with great history), accounting for 1.5% of the GDP and 2.3% of the population of the EU. It is also a very open economy, with international trade representing more than 100% of GDP and a significant dependence on external capital flows.

Portugal held national elections on 10 March 2024, and on 25 April it will commemorate 50 years of the return of democracy. However, in spite of very significant external support, free access to the large EU markets, and monetary stability brought about by euro area accession, the Portuguese population has not become better off for over a generation. Why such a disappointing outcome, what can be done and what are the lessons for other EU countries? The short answer is public policies biased towards current consumption and not towards private sector-led development. This column will elaborate on that.

Converging before EU accession

Portugal was under a dictatorial regime from 1926 until 1974, when the ‘Carnation Revolution’ heralded the overthrow of the dictatorship by the Portuguese military. During most of the dictatorship period, Portugal was under the ‘Estado Novo’ (the ‘New State’), a nationalist regime that, however, implemented a series of economic liberalisation and integration measures, particularly after the end of WWII. The country benefited from financial support from the Marshall Plan, joined the European Free Trade Association and the OECD in 1960, and signed a free trade agreement with the European Economic Community (EEC), the predecessor to the EU, in 1972.

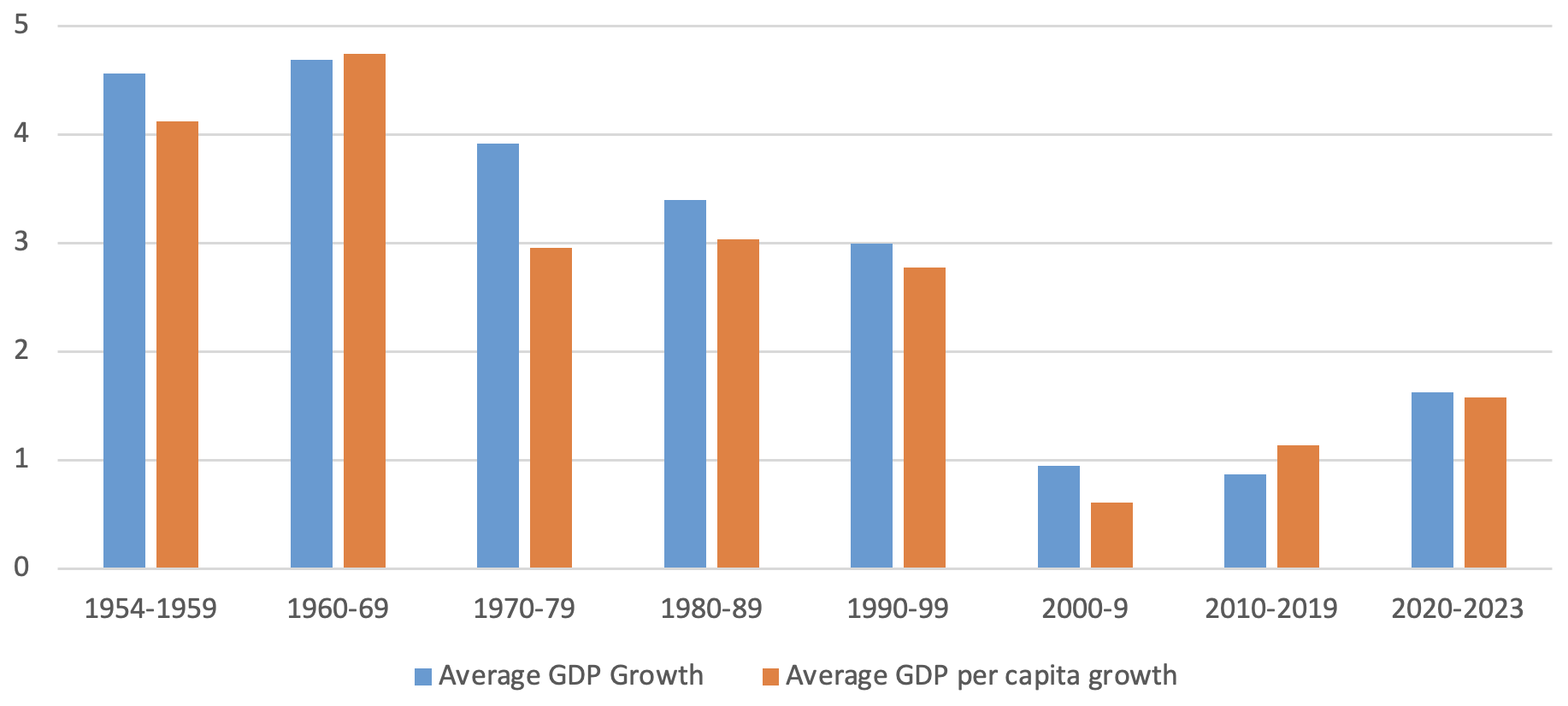

The result was that Portugal registered a strong process of liberalisation and economic integration that lasted from the mid-1950s to 1973, with important effects in terms of ‘real convergence’ – that is, the approximation of the country towards higher levels of development. The average growth rate of GDP and GDP per capita during the period between the mid-1950s and the Portuguese EU accession in 1986 was actually twice as high as during the post-EU accession period: respectively 3.9 % versus 2.0%, respectively, for GDP growth, and 3.4% versus 1.9% for GDP per capita growth (Figure 1).

Figure 1 Average growth in GDP and GDP per capita in Portugal (%)

Source: Banco de Portugal (BdP) and Instituto Nacional de Estatística (INE).

Real integration was led by a historically unique set of large and diversified family-owned Portuguese industrial and financial conglomerates, similar to the Japanese zaibatsus – the Companhia União Fabril (CUF), the Champalimaud Group, the Espírito Santo Group, Banco Português do Atlântico, Banco Borges & Irmão, Banco Fonsecas & Burnay and Banco Nacional Ultramarino – which, according to some estimates, had a combined turnover of around 75% of the Portuguese 1974 GDP (CUF, for example, was ranked among the 200 largest companies in Europe in the early 1970s,and was the largest company in the Iberian Peninsula; see Ferreira da Silva et al. 2015).

Not converging after EU accession

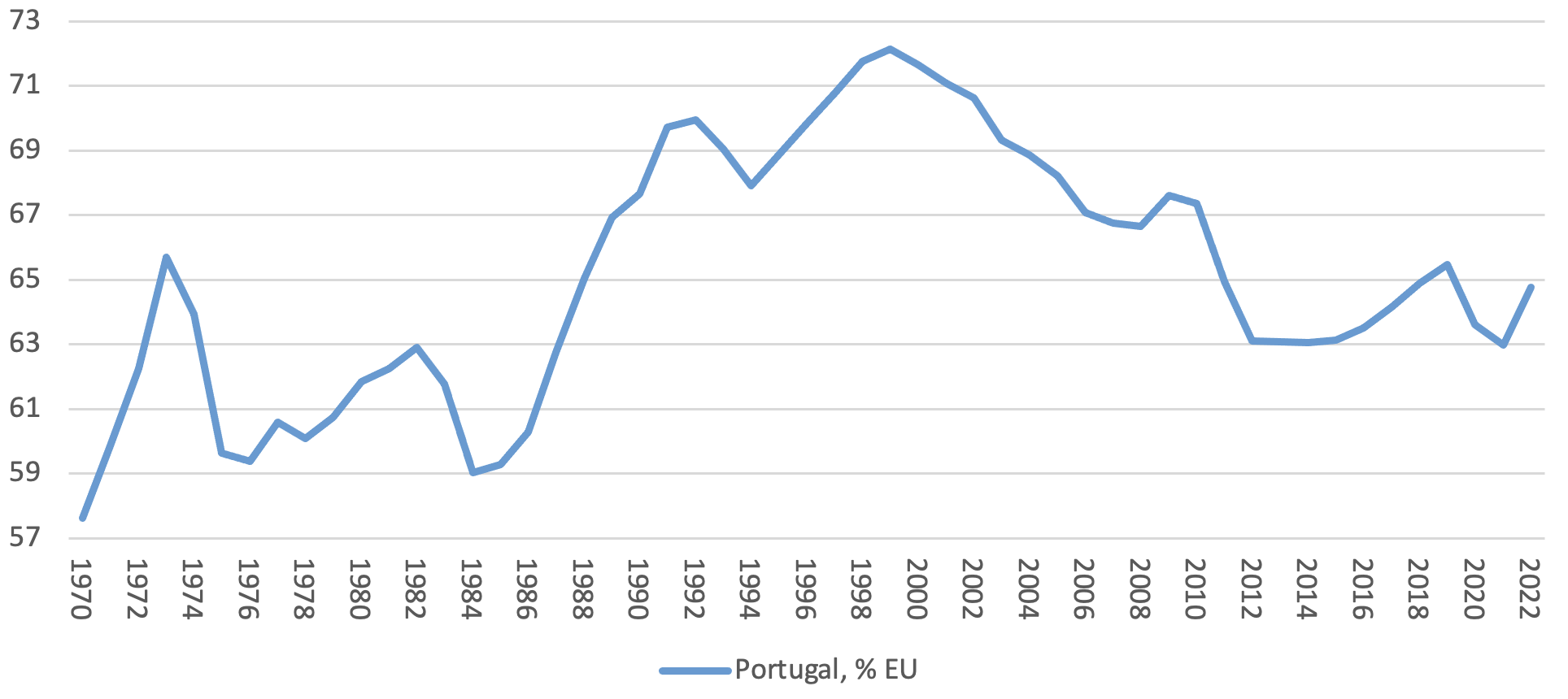

Portugal submitted its application for membership of the EEC on 28 March 1977 and became an EU Member State on 1 January 1986, but its real economic convergence reversed soon afterwards: adjusting for price levels (Portugal, poorer than the EU average, has lower prices for non-tradable goods and services), Portugal’s GDP per capita in relation to the EU reached 66% in 1973, before the Carnation Revolution, fell to 59% in 1985 before Portugal’s entry into the EU, reached a maximum of 72% in 1999, falling afterwards almost continuously to below 65% (i.e. below the value in 1973) in 2022 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 GDP per capita in Portugal, as a percentage of the equivalent value of the EU

Source: World Bank.

This result is even more surprising given that Portugal benefited (and still benefits) from very significant EU unilateral transfers: the total of all the different types of EU support over time is close to half of Portugal’s GDP. Portugal also joined the euro in 1999, which was expected to have supported real convergence as it not only eliminated the economic costs of a separate currency in interactions with other euro area economies (Portugal's largest economic partners) but also implied more favourable financing conditions and less uncertainty for all economic agents. Yet, convergence stopped. Why?

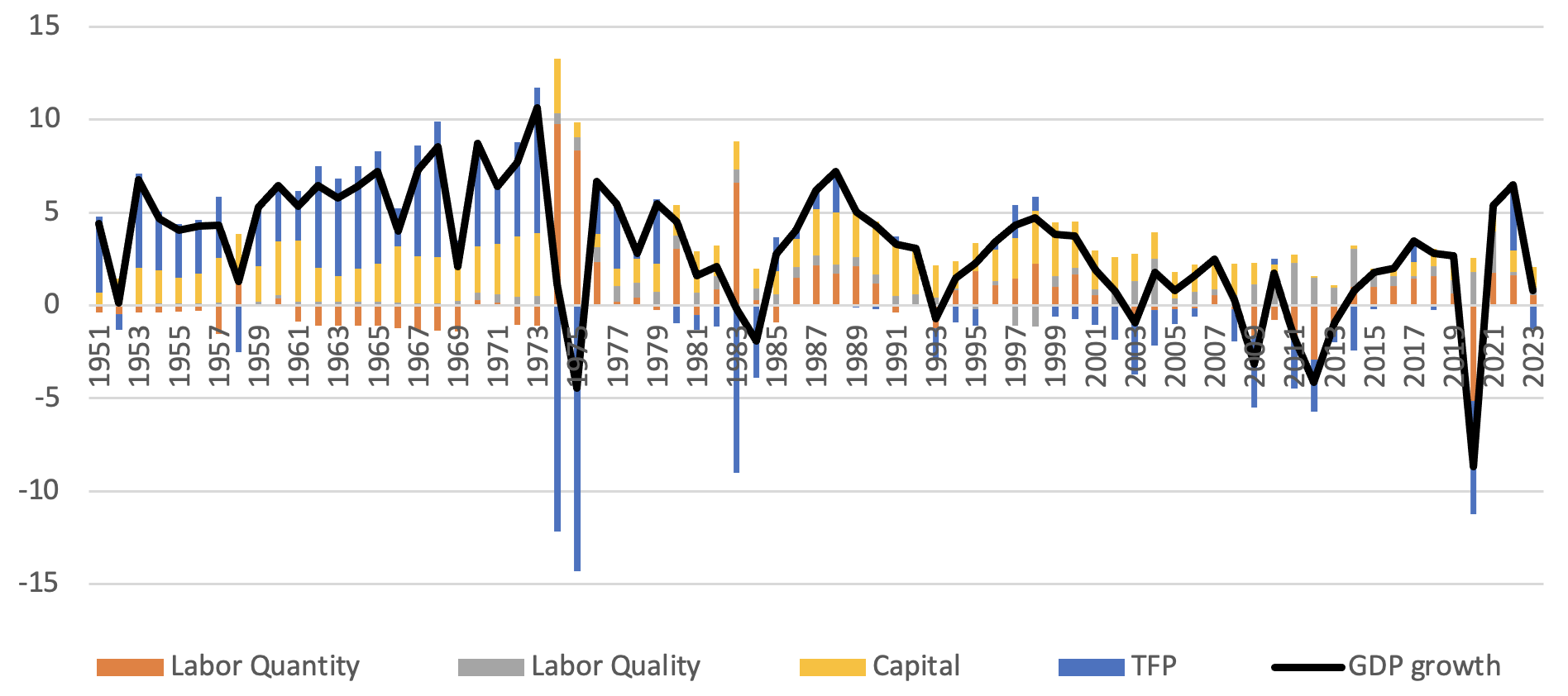

Carrying out a growth decomposition exercise helps to understand what led to this result (Figure 3): the contribution of the quantity of labour remained at similar levels before and after accession, while contribution of the quality of labour to growth almost doubled (due to the accumulation of human capital). However, the contribution of capital (i.e. physical investment) to growth decreased by around 30%, while the contribution of total factor productivity (TFP), a proxy for technological progress, became negative. In other words, most of Portugal’s reduction in growth and convergence since EU accession is associated with these (related) falls in capital and TFP, which are likely related to the nature of the ecosystem of Portuguese private companies post-1974 and to public policies.

Figure 3 Decomposition of growth drivers for Portugal, 1951-2023

Source: Conference Board.

Firms, investment, and (big) government in Portugal

The Carnation Revolution led to the deliberate dismantling of the large Portuguese privately owned conglomerates. As a result, Portugal’s economy became heavily dominated by small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs): currently, only 0.1% of Portuguese companies are classified as ‘large’ (i.e. with more than 250 employees and an annual turnover exceeding €50 million), while 96% of all companies are classified as ‘micro’ (i.e. with fewer than 10 employees and less than €2 million in annual turnover).

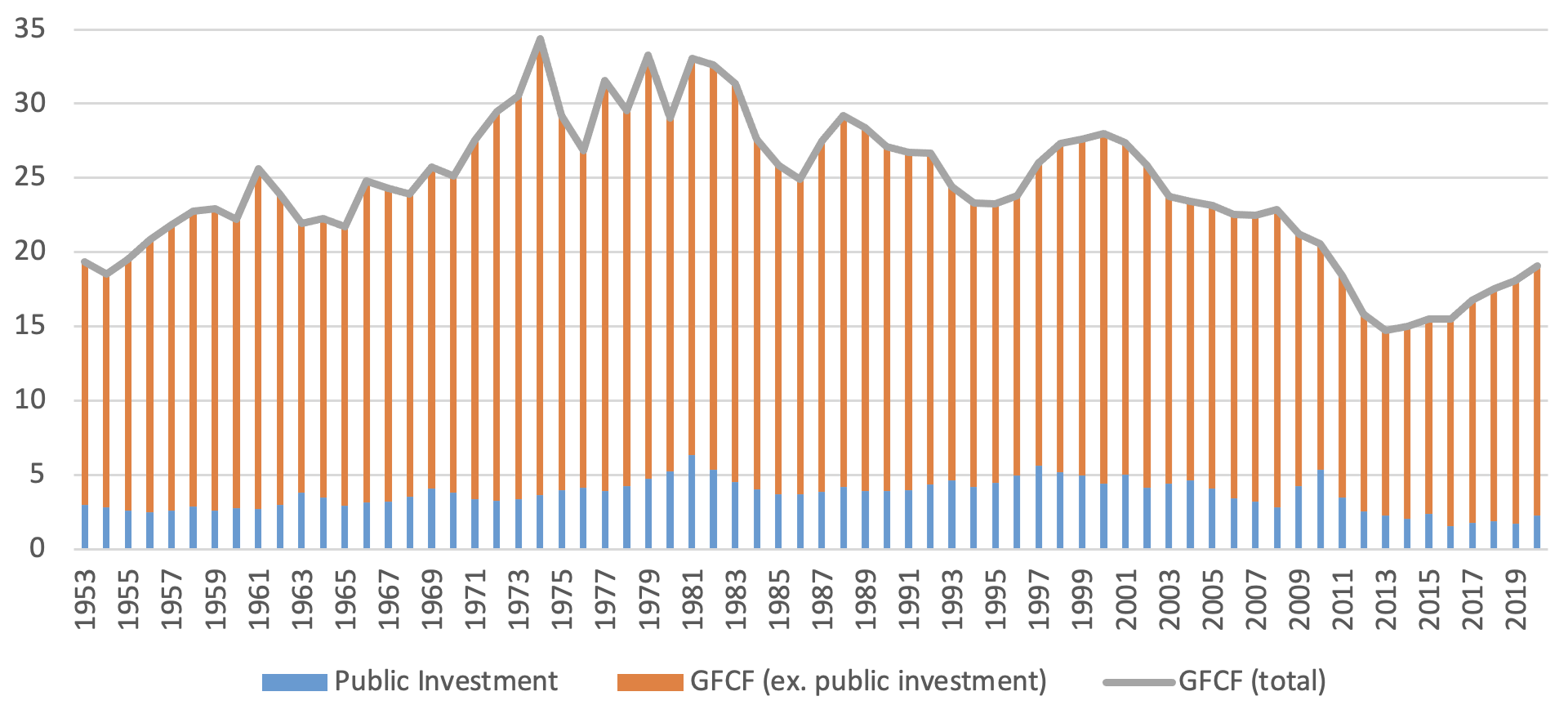

These Portuguese micro-companies tend to operate in less sophisticated and non-tradable sectors: while 5% of Portuguese companies in 2021 were in manufacturing, 30% were in sectors like restaurants, hotels, and real estate. These types of companies invest little, and even less in research and development activities (below 1% of GDP in 2020). As a result, total investment fell from almost 35% of GDP in 1974 to 19% in 2020 (Figure 4).

Figure 4 Gross fixed capital formation and public investment (% of GDP)

Source: BdP and INE, IMF.

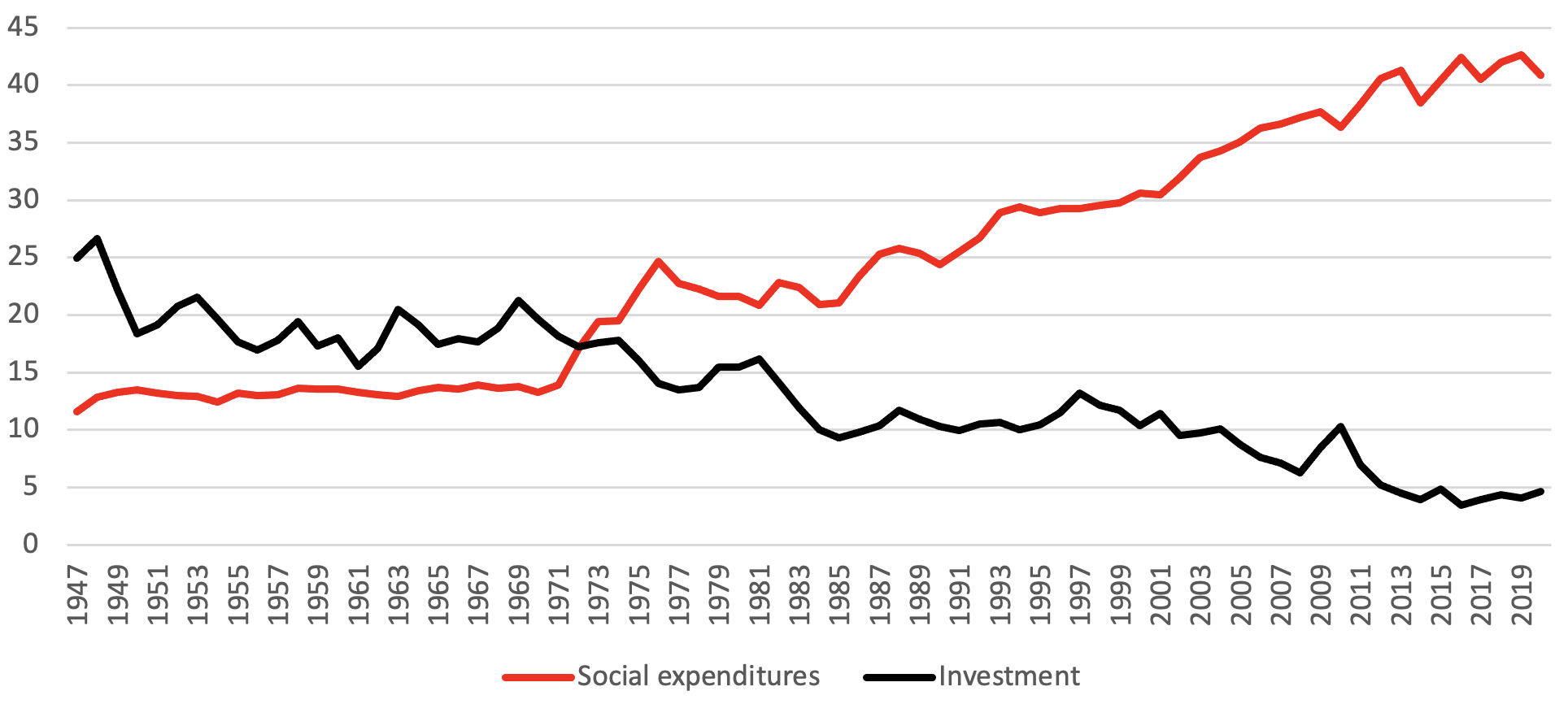

Portugal has also become a ‘big government’ country, with tax revenues having more than doubled as a percentage of GDP between 1974 and 2021, from 20% to around 45%. This greatly increased revenue is mostly used for social benefits (pensions, public health, etc.), which more than doubled as a share of total state expenses, reaching more than 40%, at the same time that investment collapsed to less than 5% (Figure 5). Additionally, the tax and regulatory burdens are above the EU average.

Figure 5 Evolution of types of government expenditures in Portugal (% of total)

Source: BdP and INE, IMF.

Less, but more: The role of human capital

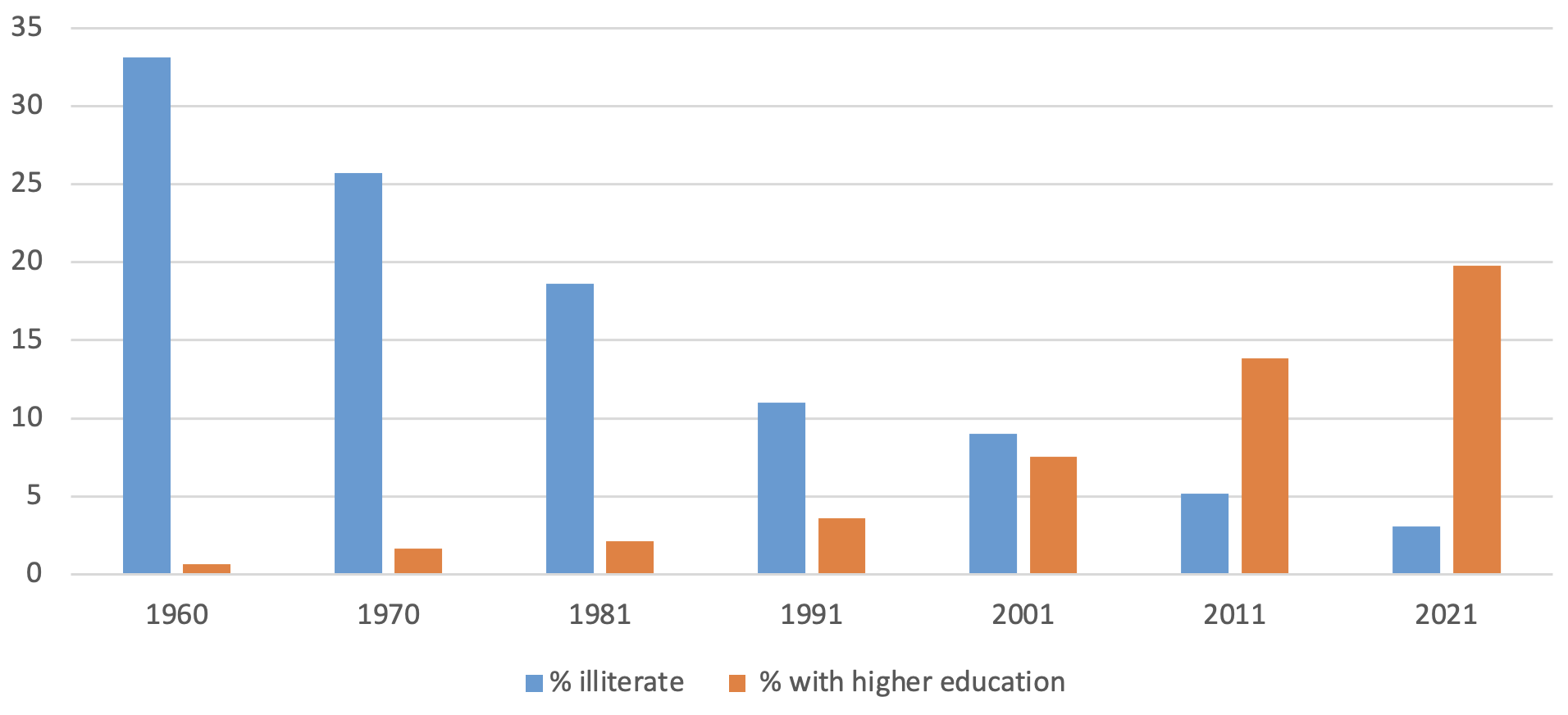

The positive side of the growth decomposition above was human capital accumulation. The process through which this happened is intuitive. The Portuguese population migrated from rural to urban areas (that is, from lower productivity activities to higher productivity activities), at the same time acquiring higher levels of human capital, which rose sharply in the country: more than a third of the total population were illiterate in 1960 and less that 1% of the population had a higher academic qualification, whereas by 2021 around 20% of Portuguese people had a university qualification and only 3% were illiterate (Figure 6).

Figure 6 Education levels of the Portuguese population

Source: INE, World Bank.

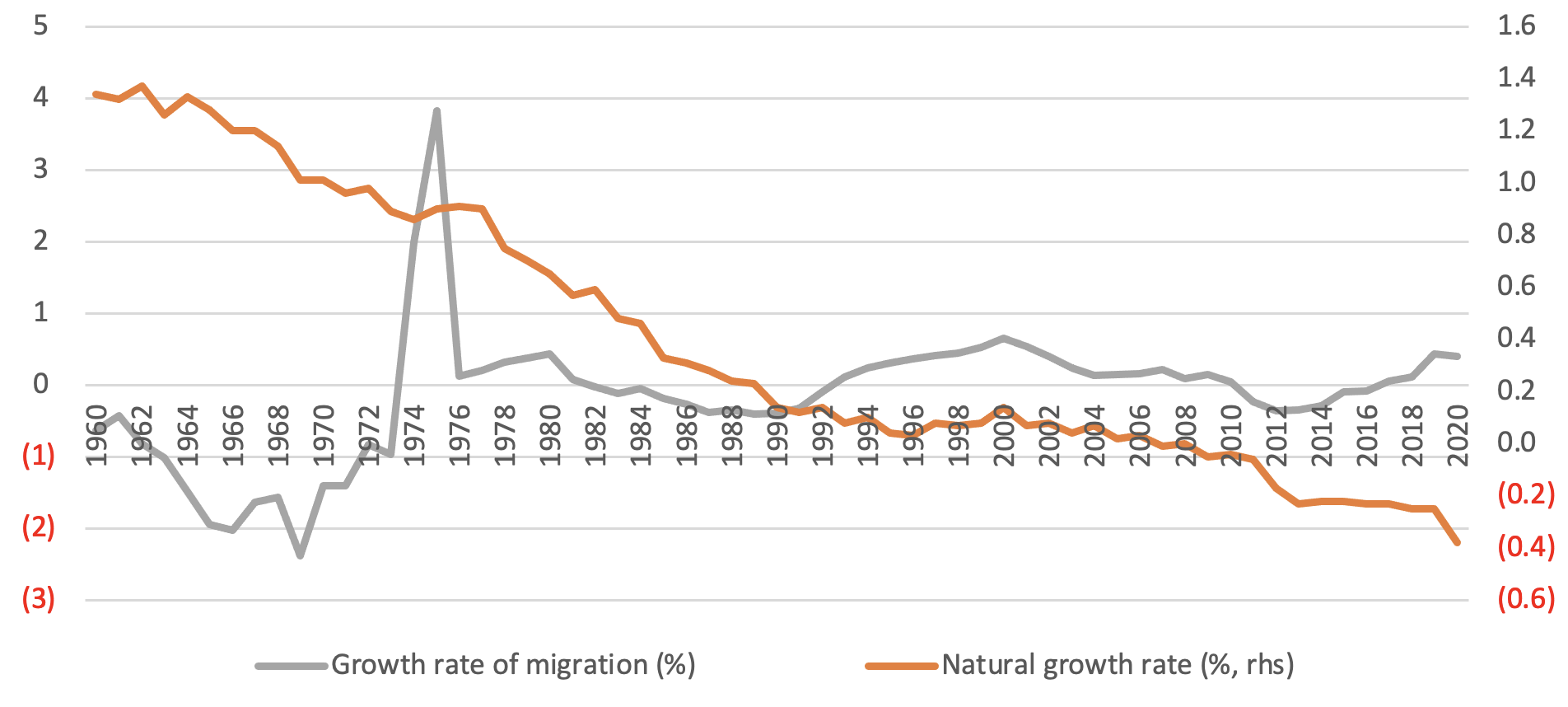

However, further increasing the amount of human capital faces challenges, given the already high percentage of the urban population and the ageing and decline of the Portuguese population, which decreased by almost 300,000 inhabitants between 2010 and 2020, with this drop only partially offset by migration.

It is also necessary to take into account the internal absorption capacity of this more qualified workforce. The country now has net emigration, so the decrease in the total population is due to both a birth rate below the replacement level (this has been the case since 1982, and with a figure of 1.4 births per woman in 2021, it is the lowest in the EU) and net emigration. This is a highly qualified net emigration (‘brain drain’), with almost half of all Portuguese emigrants in 2021 having a higher academic qualification (more than twice the percentage across the whole population). Surveys suggest that the main reason for emigration is the lack of jobs: 24% of those aged between 16 and 24 in Portugal were unemployed in 2023 (compared with 5% of those between 25 and 74 years old).

Figure 7 Growth dynamics of the Portuguese population

Sources: BdP and INE, and World Bank.

Heroes of the Sea, once more?

“Heróis do Mar” (“Heroes of the Sea”) is the first line of the Portuguese national anthem, referring to the country’s courageous exploration of the Atlantic Ocean in the 15th and 16th centuries. Sadly, the country has failed to capitalise on the opportunities provided by EU accession, and as a result has regressed in terms of economic development for almost a quarter of a century. It will also face serious adverse factors in the future, as its population is both ageing and shrinking, and its productive structure is heavily biased towards firms that do not invest, are too small, and too concentrated in traditional non-tradable sectors.

In this column, I conclude that the fundamental reason for this outcome is inadequate government policies that destroyed a previously existing productive ecosystem and that restricted the national private sector’s capacity for growth, innovation, and investment, while at the same time significantly expanding the state’s non-productive current expenditures and its regulatory and tax footprint.

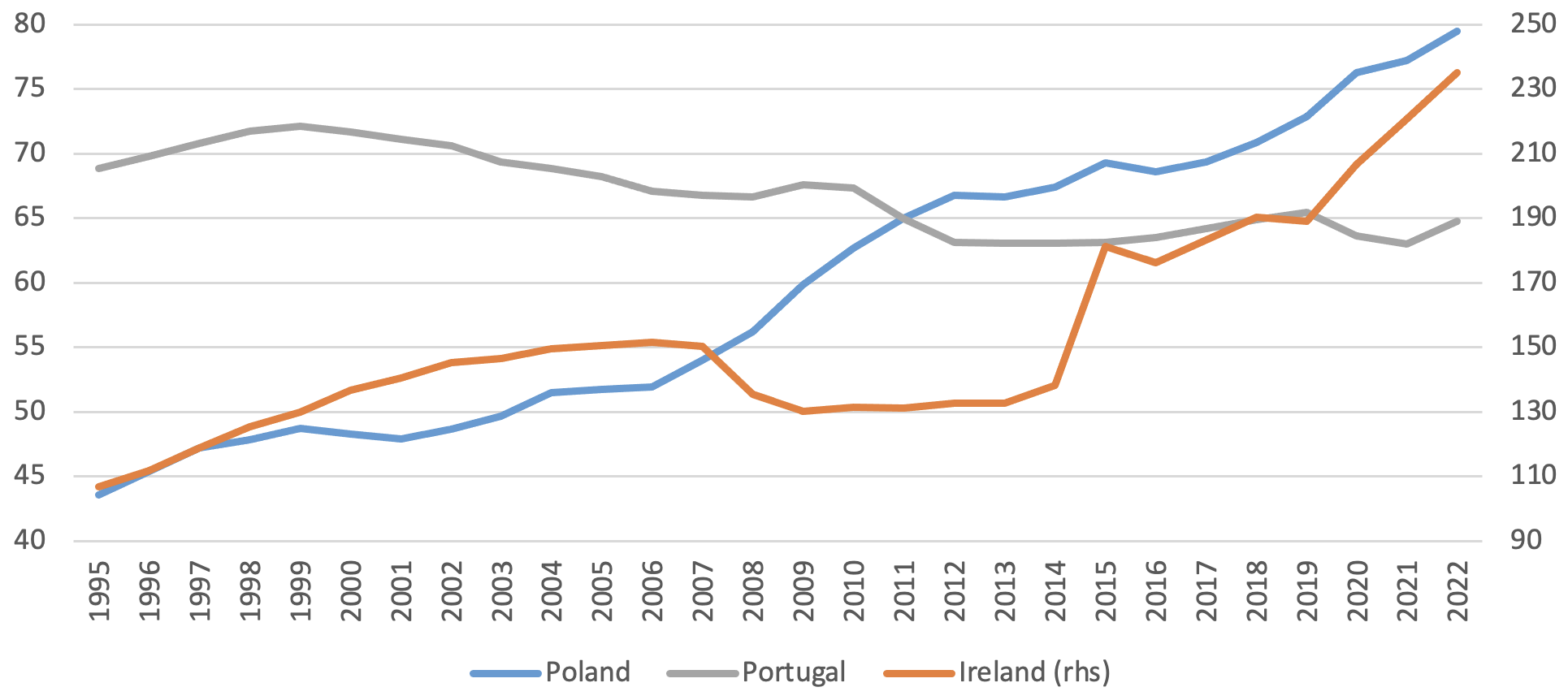

These shortcomings can be corrected by policies that are more supportive of a private sector-led development, incentivising firms to grow larger, produce more sophisticated products, and exit the market faster when they fail, and by making efforts towards higher qualification of older labour force cohorts and immigrants. Countries like Ireland and Poland, which opted for a development strategy based on creating favourable conditions for private investment (domestic, from the EU, or from outside the EU), supporting investment in tradable sectors and by linking their economies with EU and global supply chains, show how powerful this strategy can be for convergence (Figure 8).

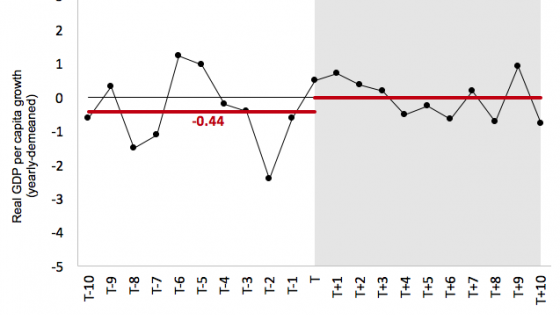

Figure 8 Convergence in Ireland, Poland and Portugal (GDP per capita, % of EU average)

Source: EUROSTAT

The new political cycle about to start in Portugal and the EU, plus the natural reflections associated with the anniversary of the Carnation Revolution, provide a golden opportunity for such changes.

Another conclusion is that EU membership is not a ‘silver bullet’. Being an EU member is better understood as providing several instruments which, if properly used, can significantly support convergence (Vinhas de Souza et al. 2018). However, this positive result depends on the choice and implementation of a specific set of policies, as Ireland and Poland show.

Author’s note: This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of any organisation to which the author is or was affiliated with. All usual disclaimers apply.

References

Ferreira da Silva, A, L Amaral and P Neves (2015), “Business Groups in Portugal in the Estado Novo Period (1930–1974): Family, Power and structural change”, Business History 58(1):49-68.

Naudé, W and M Cameron (2020), “Export-Led Growth after COVID-19: The Case of Portugal”, IZA Discussion Paper No. 13875.

Vinhas de Souza, L, O Dreute, V Isaila and J-M Frie (2018), “Reviving convergence: making EU member states fit for joining the euro area”, in E Nowotny, D Ritzberger-Grünwald and H Schuberth (eds), Structural Reforms for Growth and Cohesion: Lessons and Challenges for CESEE Countries and a Modern Europe, Edward Elgar.