COP28 highlighted the critical role of green technology and innovation in driving emissions reduction and sustainable development and achieving the ambitious net zero goal by 2050 (UNFCCC 2024). It follows the European Green Deal’s target for the EU to become a net-zero emissions region by 2050. To achieve this target, widespread adoption of existing technologies and the development of innovations are needed (van der Ploeg and Venables 2023).

However, innovation, particularly green innovation, faces significant challenges due to market failures pertinent to both environmental externalities and innovation production, highlighting the crucial role of institutions and policies. Achieving the 2050 target requires a more cohesive policy approach, where states coordinate their strategies. In the EU for instance, research suggests that uniform carbon pricing could serve as an effective and efficient strategy in diminishing emissions (Schmidt et al. 2021).

Further, we must acknowledge the disparities among EU member states in technological readiness, availability of skilled labour, and innovation capacity (Santoalha et al. 2021). By identifying best practices and constraints across states, policymakers can devise strategies to enhance overall performance and address existing limitations.

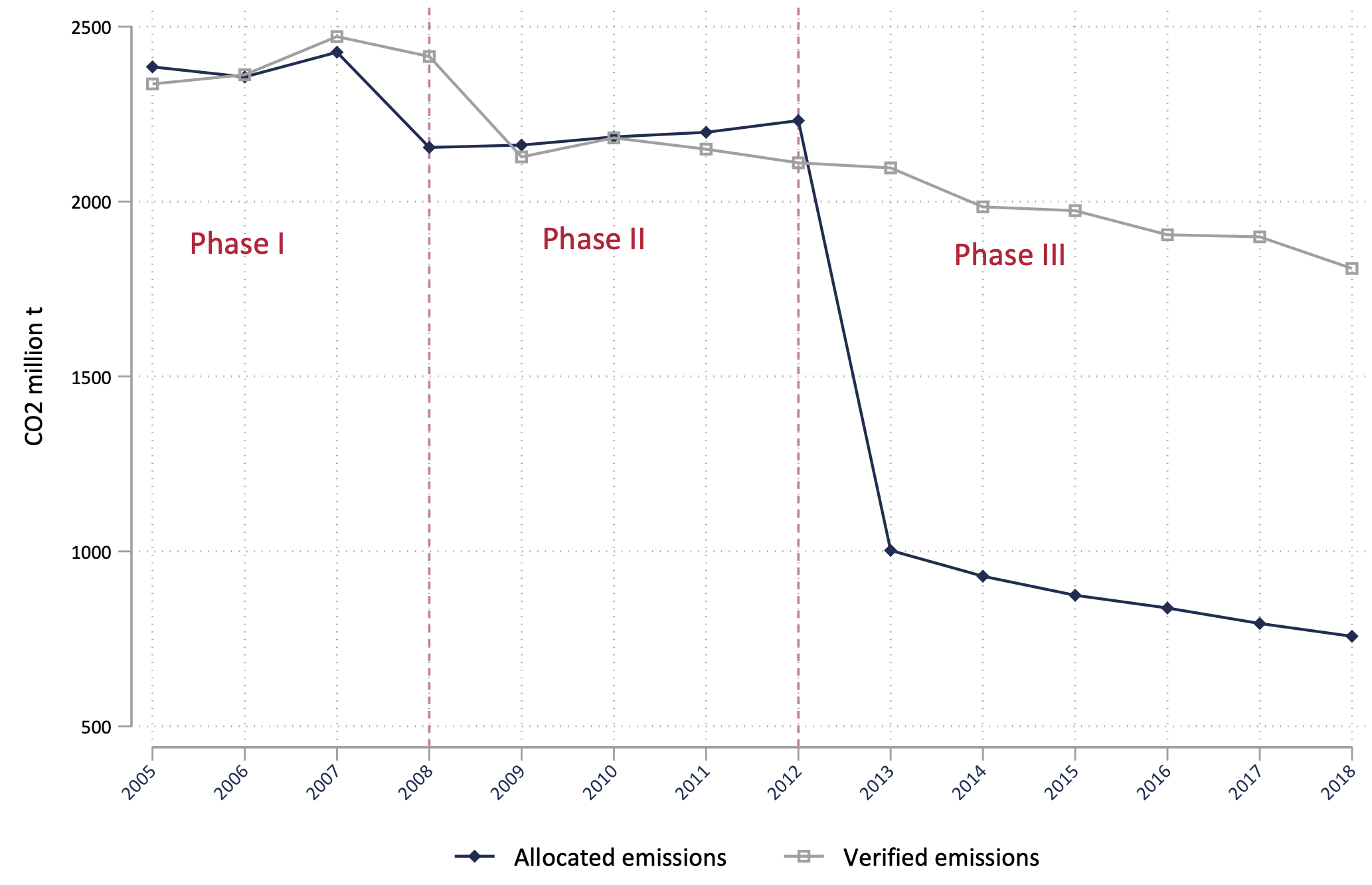

The EU Emissions Trading System (EU ETS) stands as the flagship cap-and-trade regulation. It is the first and largest market for greenhouse gas emissions worldwide, covering more than 11,000 manufacturing and power plants and more than 45% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions in its current form. The primary objective of EU ETS is to incentivise firm-level innovation away from carbon-intensive technologies through price signalling. Consequently, EU ETS provides a unique opportunity to examine how industries and firms respond to the incentives of this market-based mechanism that imposes a financial cost on emitting carbon. Figure 1 depicts the evolution in actual (verified) and allocated emissions during the first three phases of the EU ETS.

Figure 1 Total allocated and verified CO2 emissions of all firms participating in the EU ETS, 2005–2018

Empirical findings on the effectiveness of ETS have been mixed. For instance, research focusing on the Italian manufacturing sectors, conducted by Borghesi et al. (2015), suggests that firms subject to the EU ETS regulation exhibit a greater propensity for environmental innovation, whereas the stringency policy environment has led to a diminishing effect on innovation diffusion when compared to the non–EU ETS firms. Similarly, Andreou and Kellard (2021) find poorer firm performance for environmentally proactive firms within the EU ETS framework. In contrast, Ren et al. (2022) highlight a positive impact on the environmental and performance measures as well as an increase in environmental innovation for firms related to the ETS framework in China.

In Andreou et al. (2023), we depart from conventional approaches by delving into the interplay between national structural characteristics and the aptitude of the EU ETS, while accounting for idiosyncratic firm attributes. Our central hypothesis posits that a sound institutional framework fostering innovation and technology investment at the national level positively impacts firms’ ability to reduce emissions.

To analyse the channels that connect national attributes and environmental degradation as measured by firms’ emissions, we exploit a rich novel dataset which merges firm-level verified greenhouse gas emissions, with firm-level financial data and a comprehensive set of national indicators from the IMD World Competitiveness Center and the World Economic Forum.

Our analysis covers 540 firms across 31 European countries over the period 2005–2018. We find a significant negative relation between national structural characteristics and firms’ verified emissions per installation, even after controlling for idiosyncratic firm properties. The emissions-mitigating effect of sound institutions is robust even when controlling for R&D spending at the country level as well as the stringency of environmental policy. In general, environmental policies intend to align firm incentives with emissions reduction, which promotes innovation for transitioning to a low-carbon economy. Conversely, institutional environments foster knowledge accumulation and assimilation which are pivotal for green innovation.

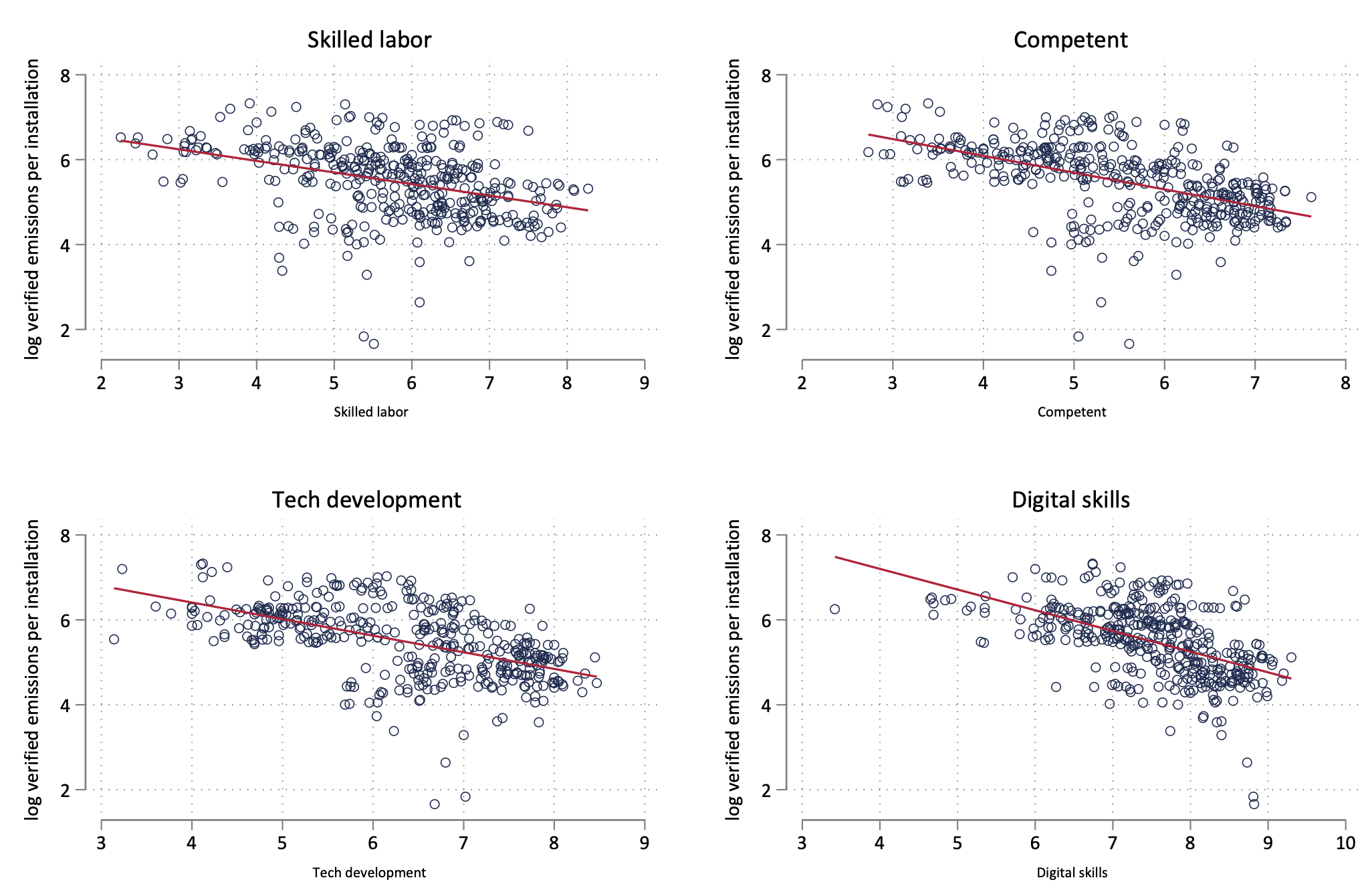

One striking revelation is the significant influence of skilled labour and competent managers on emissions reduction efforts. For instance, increasing the indicator of skilled labour by one standard deviation decreases firms’ emissions per installation by 21.4%, whereas the same improvement in the competent-managers indicator is associated with a 21.1% drop in emissions per installation. The results reveal a sizeable emissions abatement effect; however, in practice, such improvements in structural attributes imply substantial transformation at the national level. For example, an increase of one standard deviation in skilled labour would elevate Cyprus from the middle of the EU country table to the second place below Ireland. In the same vein, using 2018 data, a one-standard-deviation improvement in the competent-managers indicator translates into an increase in country ranking by ten positions.

Figure 2 shows the correlation between the (log) verified emissions per installation and skilled labour on the top-left plot, and competent managers on the top-right plot.

Figure 2 Labour market efficiency, technological infrastructure, and emissions for EU ETS countries, 2005–2018

Notes: Scatterplots of indicators from the IMD World Competitiveness Ranking capturing labour market efficiency and technological infrastructure for countries that participated in EU ETS, 2005–2018. Country names are included in the graphs of the working paper Andreou et al. (2023).

The bottom-left plot of Figure 2 shows that improving the technological infrastructure (for instance, the number of computers per capita) decreases substantially the firms’ emissions per installation. In particular, increasing the indicator of technological development by one standard deviation (enough to reposition Greece above Germany and Belgium, using 2018 data) decreases firms’ emissions per installation by 11.5%. An increase in the indicator assessing the availability of digital skills in a country, as depicted in the bottom-right plot, leads to a 16% reduction in firms’ emissions per installation. A transformation of this size would move a laggard country very close to the average performer for the 2010–18 period. Our results align with previous calls for government investments in technological infrastructure and addressing the gaps in the necessary competences (Cervantes et al. 2023, Schmidt and Schögl 2020).

Moreover, our study underscores the importance of fostering collaboration between the public and private sectors in technological-development ventures. For instance, a one-standard-deviation increase in public-private partnerships is linked to a noteworthy 14.1% decrease in firm emissions.

Our research also highlights the critical significance of accountability. The EU ETS Phase III in 2013 introduced reforms such as the implementation of the auctioning system and the introduction of the market stability reserve. These measures effectively address the persistent challenge of allowance oversupply leading to a decline in the allocated permits. Consequently, firms are compelled to incorporate the cost of auctioned emission allowances into their strategic decisions. As illustrated in Figure 1, incentives for reducing emissions intensified, as corroborated by our empirical findings that emphasise the pronounced emissions-abating effect of national attributes during Phase III.

Policy implications

While environmental policies can potentially create positive outcomes, sound institutions at the national level must act as facilitators and catalysts for businesses to adopt sustainable practices, innovate, and invest in clean technologies. Our research offers clear policy implications that could guide decision-makers across both the public and private sectors.

First, there is a pressing need to address the skills gap through investments in education and training programmes. These initiatives should extend beyond traditional workforce development to include programmes for managers, ensuring that the talent pool has the necessary competencies to drive the green transition forward. This is in line with the “Learning for the green transition and sustainable development” recommendation of the Council of the EU (European Commission 2023).

Second, policymakers should prioritise investments in technology and infrastructure to facilitate emissions-reduction initiatives. This includes funding R&D projects as well as improving the technological capabilities of industries. One suggested approach is to utilise revenues from the auction of EU ETS emission allowances, as suggested by the Innovation Fund.

Third, fostering collaboration among stakeholders is paramount. Bringing together the public sector, academia, research centres, think tanks, and the private sector will allow policymakers to leverage diverse expertise and talent to accelerate progress towards sustainability goals. Achieving lasting and significant change requires joining forces with multiple stakeholders across industry, government, the research community, and civil society. This approach resonates with the European Green Deal’s call for “an open dialogue with all concerned, including farmers, businesses, social partners and citizens” (EC 2024).

Lastly, policymakers must establish robust monitoring and evaluation mechanisms to assess the effectiveness of the emissions-reduction efforts. This is critical for identifying areas of strengths and areas requiring improvement, confirming that incentives remain feasible and effective in driving the green transition forward.

References

Andreou, P C, S Anyfantaki, C Cabolis, and K Dellis (2023), “Exploring country characteristics that encourage emissions reduction”, Bank of Greece Working Paper 323.

Andreou, P C, and N M Kellard (2021), “Corporate environmental proactivity: Evidence from the European Union’s Emissions Trading System”, British Journal of Management 32: 630–47.

Borghesi, S, G Cainelli, and M Mazzanti (2015), “Linking emission trading to environmental innovation: evidence from the Italian manufacturing industry”, Research Policy 44: 669–83.

Cervantes, M, C Criscuolo, A Dechezleprêtre, and D Pilat (2023), “Fostering innovation for climate neutrality”, VoxEU.org, 1 June.

European Commission (2023), “The Green Deal Industrial Plan: Putting Europe’s net-zero industry in the lead”, press release, 1 February.

European Commission (2024), “Recommendation for 2040 target to reach climate neutrality by 2050”, Directorate-General for Communication, 6 February.

Ren, S, X Yang, Y Hu, and J Chevallier (2022), “Emission trading, induced innovation and firm performance”, Energy Economics 112: 106157.

Santoalha, A, D Consoli, and F Castellacci (2021), “Digital skills, relatedness and green diversification: A study of European regions”, Research Policy 50: 104340.

Schmidt, C, and R Schlögl (2020), “Making the European Green Deal really work”, VoxEU.org, 23 November.

Schmidt, C, K Schubert, I Mejean, X Ragot, P Martin, C Gollier, C Fuest, N Fuchs-Schündeln, and M Fratzscher (2021), “Pricing of carbon within and at the border of Europe”, VoxEU.org, 6 May.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) (2024), “How climate technology is being ramped up”, 9 January.

van der Ploeg, F, and A Venables (2023), “Radical climate policies”, VoxEU.org, 25 February.