In June the US Congressional Budget Office (CBO) updated the budget outlook for the US (CBO 2024): the US federal debt (held by the public) is projected to grow from 99% of GDP in 2024 to 122% in 2034 – "higher than at any point in history”.

The US interest bill is rising. In 2024, it is projected to exceed the entire military budget. Starting from the CBO outlook, we use fiscal simulations to address three questions. First, what would it take to stabilise the US debt and interest payments in the next few years? Second, can we reasonably expect the US to grow out of its problems? Lastly, what would be a reasonable path out of the current mess, in terms of a combination of spending and tax measures? To produce our simulations, we rely on the FRB-US model, which is a large-scale estimated model of the US economy. FRB-US accounts for the full general equilibrium effects of the policy measures we consider in our scenarios, hence for the indirect fiscal implications of changes in economic activity (on tax revenue and deficits), unemployment (on spending), and interest rates (on the interest bill).

Our main results are summarised below:

- No matter what fiscal consolidation plan we assume, the debt/GDP ratio increases at least until 2026-2027. The same is true for net interest payments.

- Cutting public spending (‘G’) permanently by 1% of GDP has limited effects on the debt/GDP ratio – it would not deliver debt stabilisation.

- Targeting a stable deficit/GDP ratio in the next few years requires a significant increase in the average tax rate on personal income, possibly too large to be politically acceptable. Yet, it would not be enough to stabilise the debt/GDP ratio.

- Even assuming a sustained growth scenario (2.5% real GDP year-on-year), without fiscal consolidation the debt/GDP ratio would not stabilise: the fiscal problem is too large to be offset by growth.

- A recession could make everything worse, as (given the size of the debt) a fall in yields reducing the interest bill would be more than offset by larger primary deficits.

- Any attempt to stabilise the debt/GDP ratio over a short horizon, e.g. already by 2026, would require draconian hikes in (personal income) tax rates, with harsh consequences for the economy. It would be counterproductive, let alone politically unfeasible.

- The way to achieve a stable debt/GDP dynamic is a smooth consolidation plan over a long horizon. Yet, even in a decade-long plan ending in 2034, this would require substantial adjustment already in the short run. Waiting is costly (the adjustment is larger) and risky (it may become difficult if markets become wary or if a negative shock hits the economy).

We substantiate these points with an analysis of fiscal consolidation scenarios that we have constructed using FRB-US, envisioning spending cuts, tax hikes, and a combination of the two, as well as varying the US growth rates, over different time horizons. For each scenario, we include two graphs, showing the associated dynamics of the deficit/GDP and debt/GDP ratios (in grey) against the no-policy change baseline (red dashed lines). Our discussion nonetheless refers to the entire model output, which includes real GDP growth, the unemployment rate, the federal funds (FF) rate, financial variables (i.e. five-year or ten-year yield), the average tax rate on personal income, and the net interest payment as a ratio of GDP.

The next three years

Main takeaway 1: No matter what fiscal consolidation plan we assume, the debt/GDP ratio increases at least until 2026-2027.

Scenario #1: Federal spending cut

We start with a consolidation consisting of a permanent cut in (discretionary) government spending by 1% of GDP achieved by lowering federal purchases by about 20%. Cutting ‘G’ lowers real GDP growth for one year, increases the unemployment rate, and results in a lower FF rate.

It does reduce the deficit/GDP ratio marginally, but it does next to nothing to contain the debt/GDP dynamics, which remain explosive. The net interest payments also keep rising. We should note here that the deficit/GDP ratio in the FRB-US simulations is higher than in the CBO outlook, partly reflecting higher expected yields. The difference in yields, however, is inconsequential for our main conclusions (we return to this point below).

Scenario #2: Stabilising deficits by 2026, no cut in spending

In our second scenario, we refocus on the deficit and taxation. We ask the model to stabilise the deficit/GDP ratio at around 8% by 2026, around 1 percentage point below the CBO projections, without cutting ‘G’. According to FRB-US, this would require raising the average tax rate on personal income by about four percentage points, from around 14% to around 18% (an adjustment of about 3% of GPD). Alas, despite the significant tax increases, the debt/GDP continues to grow, as the deficit, although improving, remains too large. This scenario implies conclusions that are quite similar to the CBO baseline.

A combination of scenarios #1 and #2, positing a permanent cut of ‘G’ by 1% of GDP and an increase in the average tax rate on personal income of three percentage points by 2026 (one percentage point lower than in scenario 2, given the contribution of the cut in spending) will result, relative to the previous scenario, in an anaemic real GDP growth and higher unemployment, with very similar dynamics for the deficit/GDP ratio and debt.

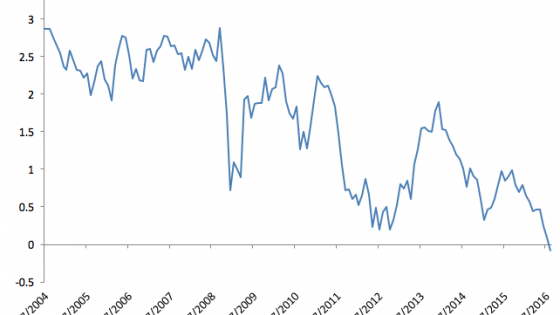

A somewhat better fiscal outlook could follow from a favourable dynamic of borrowing costs. In the FRB-US model the evolution of yields is endogenous, hence (with a deteriorating fiscal outlook) less favourable than assumed by CBO. Specifically, comparing the FRB-US with the CBO baseline, the ten-year yield is expected to average about 50 basis points higher. Throughout our simulations, a lower ten-year yield in line with the CBO assumption would of course mitigate the debt/GDP dynamics, but only at the margin. It would not be enough to stabilise it.

Are these scenarios surprising? Let’s square them with the simple the algebra of debt dynamics. In the US, right now, nominal GDP growth is roughly equal to long-term yields. In this case, the debt/GDP ratio stabilises only if the primary deficit close to is zero. However, the current US primary deficit is around 4% of GDP (3.8% in 2023). Therefore, given potential growth and nominal yields, the fiscal correction needed to stabilize the debt/GDP ratio is around 4 percentage points of GDP (see Bureau of the Fiscal Service US Treasury 2023 for an analysis backing the same conclusion).

Can the US grow out of its fiscal mess?

Main takeaway 2: Sustained growth helps, but it cannot solve the problem (and recession risks cannot be ruled out).

Scenario #3: Permanently higher real GDP growth

Let’s suppose that real GDP grows at a steady 2.5% going forward. This is substantially higher than the rates underlying the CBO projections, setting 2% for 2025 and 1.8% for 2026 onward. In our simulation, we raise overall growth by distributing ‘add factors’ to each component of GDP. While higher GDP results in an improved debt/GDP dynamic, absent fiscal correction the path of the debt/GDP ratio remains explosive: the fiscal benefits of higher real GDP growth are more than offset by the fiscal stance. For growth to have a significant effect, we would need to raise it on a permanent basis to a staggering – and implausible – level above 4%.

Scenario #4: Fiscal correction at risk: A recession scenario

The logical counterpart of the high growth scenario above is (the risk of) lacklustre growth. We ask the model to assess the consequence of a mild exogenous recession (-0.5% of real GDP) hitting the US in 2025. The deficit widens, as it usually does during downturns. The larger deficit (due to a lower GDP) more than offsets any reduction in borrowing costs, which may follow from a cyclical drop in yields. Consequently, the debt/GDP dynamics are worse than in the baseline.

The narrowing path ahead

Main takeaway 3: There is no quick fix: forced consolidation by 2026 would be counterproductive, let alone politically unfeasible. Success requires consolidation over a long horizon, but also immediate action.

Scenario #5: The delusional belief in fast-track consolidation, stabilising debt by 2026

As a fifth scenario, we asked the model to directly stabilise the debt/GDP ratio, setting a relatively short horizon, by 2026. According to the model, if we rule out spending cuts, such fast-track consolidation would require zeroing the deficit already by 2026Q4, by doubling the average tax rate on personal income. The impact on the economy would be quite harsh: two years of zero real GDP growth and a rising unemployment rate. Moderating the tax hike with compensating spending cuts would not change the picture – indeed, the economic impact would be harsher. It is easy to rule out this scenario: there is zero political appetitive for it.

Scenario #6: Smoothing adjustment over a ten-year horizon

In our final simulation, we extend the horizon to achieve the desired targets to 2034. To do so in FRB-US, we switch from VAR-consistent expectations to model-consistent expectations. Now, once we simulate over a long horizon, the model can deliver the required target stabilisation of the debt/GDP ratio under different combinations of measures. The scenario we show below relies on deficit targeting.

In the scenario depicted in the graph, stabilising the debt/GDP ratio by 2023 requires an immediate increase in personal income taxes of about six to ten percentage points, for at least a decade. While there could different combinations of measures achieving the same target, in no case will they be negligible or short-lived.

Conclusions

The takeaway is straightforward. Debt is on a steep rising path and, most crucially, so is the interest bill. Even substantial spending cuts and deficit-stabilising measures are at this point insufficient to stop the trend. The hope to grow out of the fiscal mess runs into a frustrating growth arithmetic: nothing short of 4% trend growth would do, by itself. At this point, fast-track consolidations would require politically unfeasible hikes in tax rates and spending cuts, with harsh consequences on the economy.

In our best scenario analysis, stabilising the fiscal outlook will take years to accomplish, but also require significant action already in the short run, operating on both spending and taxation. A consolidation over a long horizon should not be confused with procrastination. Waiting is costly: the size of the required correction is already sizeable. With debt growing at a sustained rate, delaying action can only make the required correction larger.

Even more, waiting is risky. In our simulations, we do not entertain scenario of fiscal and financial turmoil. Large debt may give rise to instability driven by self-validating expectations of a crisis.

As the recent experience in Europe suggests, attempts to stabilise the fiscal outlook when markets are jittery are often self-defeating.

The narrative ‘big fiscal was a success’ was appropriate for the pandemic years. It may be dangerous today, as it fails to recognise that, starting in 2016, before and after Covid, the fiscal stance has remained too relaxed for too long. The model prediction is crystal clear: starting now, it will likely take at least a decade to fix the excessive deficit issue. A year or two of mild measures would hardly do anything. It follows that stabilisation would require some form of bipartisan consensus on sticking to a reasonable path of fiscal adjustment for some time, whichever party governs. The worrisome question is: how many politicians and market participants are aware of the real situation, and have the means and the will to act?

References

Blanchard, O (2024), “Olivier Blanchard’s Roadmap”, LePoint.fr, 11 July.

Bureau of the Fiscal Service U.S. Treasury (2023), Financial Report of the United States Government.

Congressional Budget Office (2024), “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034”, June.

Corsetti, G and B Mackowiak (2024), “Gambling to preserve price (and fiscal) stability”, IMF Economic Review 72(1): 32 – 57.

Jiang, Z, H Lustig, S Van Nieuwerburgh and M Z Xiaolan (2024), “The U.S. Public Debt Valuation Puzzle”, Econometrica, forthcoming.

Perotti, R and L Sala (2024), “Fiscal consolidations: announcements and reality”, mimeo.