Ukraine is in desperate need of more weapons and ammunition to survive the Russian aggression and eventually regain control over its territories and win the war. This is priority number one. Priority number two, however, is to make sure Ukraine has to money to win the war – not only in theory and in principle, but actual money available when it is needed in a predictable manner and at a scale that ensures that the government of Ukraine does not have to resort to unstainable alternatives when foreign financial support does not materialise at the pace promised. This latter situation has happened more than once without being linked to developments in Ukraine but to internal issues in the major partners of Ukraine.

The IMF in its third review of the programme for Ukraine in March 2024 (IMF 2024) states (their bold/italics):

“[r]isks to the outlook (both baseline and downside) remain exceptionally large and continue to evolve amid prevailing uncertainties (Annex I). Key risks ahead include those arising from major shortfalls in external financing and/or the impact of a more intense and longer war:

- External financing shortfalls: Shortfalls or prolonged delays in donor financing could require the authorities to take prompt countermeasures to cope with liquidity pressures, which could weaken confidence and further dampen growth, and be potentially destabilizing if the uncertainties last too long.”

Predictability is also key to ensuring that other types of funding materialise (Trebesch 2023, Nell et al. 2023). In particular, private sector investments, both domestic and foreign, will require macroeconomic stability. There has been a lot of attention on war risk insurance for trade and investment focusing on the physical risks associated with doing business in a country that is being attacked by a brutal neighbour. However, macroeconomic stability is also needed to ensure that the value of the currency is maintained and that local markets for goods and services function, otherwise there will be very little private investment and economic growth will suffer.

The EU has devised a plan that would transfer some €3 billion in incomes from the excess profits Euroclear makes from managing frozen Russian assets this year. We propose using this money to finance borrowing by the partners of Ukraine, with proceeds of this borrowing put in a fund that is available in a predictable manner and at a scale that matters. The fiscal costs to the borrowing countries would be net zero, while Ukraine would gain significantly in terms of macroeconomic stability.

Although €3 billion can be a lot of money in some circumstances, the external financing need of the Ukrainian government in 2024 is estimated at €38 billion by the IMF in its programme with Ukraine. There will be further needs for foreign funding in the years to come and at levels that have to be considered highly uncertain at this point in time, regardless of what is in the IMF’s and others’ forecasts. If the difficulties to agree on funding for Ukraine continues in the US and the levels that the EU has so far agreed do not increase substantially, there will be a very significant funding gap for the Ukrainian budget that is also a significant funding gap for its needs to import goods and services in this year and years to come.

Instead of transferring the €3 billion to the European Peace Facility, as suggested by EU leaders, the money could by leveraged through borrowing by Ukraine’s partners. This could then finance a fund of €120 billion today if we use the current 10-year rate for AAA-rated Eurobonds rounded up to 2.5% as the cost of borrowing and with the goal of making the financing cost net zero. A fund of €120 billion would then be available for disbursement to Ukraine in line with the needs of the Ukrainian government and consistent with the IMF programme. To reduce both administration and uncertainty regarding disbursements from this fund, this could be done based on the same cycles and conditions as has already been agreed in the IMF programme, since this is about ensuring macroeconomic stability.

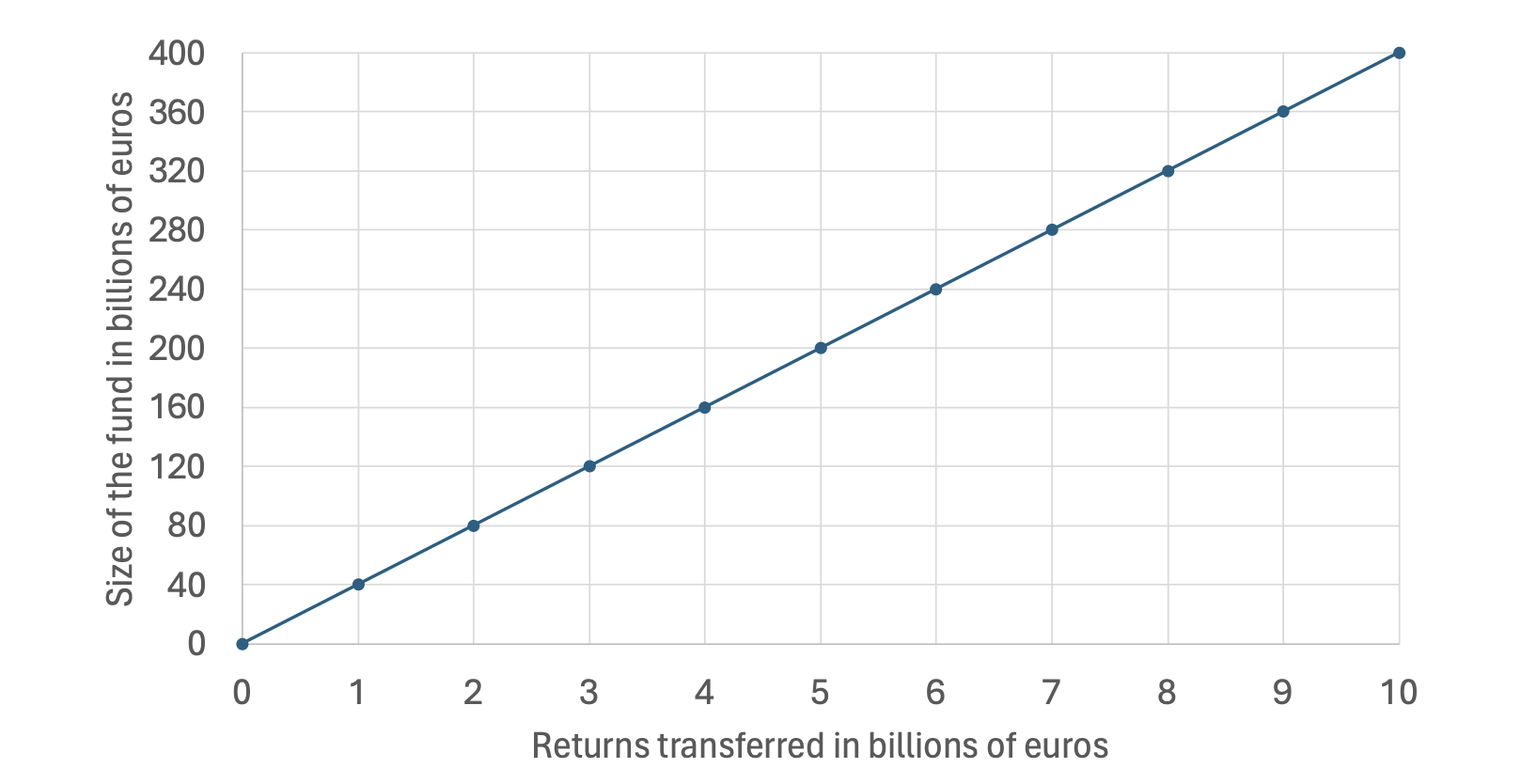

The size of the fund could be increased further if more of the frozen assets are included or if the assets held by Euroclear are invested in a manner that generates higher returns. Figure 1 shows how large the fund could be without incurring any fiscal costs to the borrowers for different levels of incomes from frozen assets. Since each extra €1 billion of transferred returns can finance borrowing of €40 billion, there are strong reasons to look for ways to generate higher returns of the frozen assets that can be used to contribute to this fund or to go beyond the assets that are now being considered for this transfer and transfer returns from all frozen Russian assets to finance this fund.

Figure 1 The relationship between the size of a fund with zero fiscal costs and level of transferred returns from Russian frozen assets if borrowing for the fund is done at 2.5%

In this example, the yield of a 10-year bond is used to do the calculation of the fund. The maturity of the borrowing could usefully be chosen such that when the bonds mature, the principles of the frozen Russian assets have also been transferred to pay the principle of the maturing bonds. In this way, there is no fiscal cost also at maturity. This further strengthens incentives for Ukraine’s partners to push the agenda of war reparations and transfer of the principals to Ukraine.

Finally, it should be made clear that this fund could only be set up with the consent of the government of Ukraine, since the people of Ukraine are the ones that should be compensated by Russia for the damages Russia is doing in Ukraine and to the people of Ukraine. However, given that the fund would provide funding at scale in a predictable manner to Ukraine, this is likely not an obstacle to the creation of this fund.

References

IMF (2024), “Ukraine: Third Review of the Extended Arrangement Under the Extended Fund Facility, Requests for a Waiver of Nonobservance of Performance Criterion, and Modifications of Performance Criteria-Press Release; Staff Report; and Statement by the Executive Director for Ukraine”.

Nell, J, B Weder Di Mauro, N Shapoval, and Y Gorodnichenko (2023), “Financing democracy: Why and how partners should support Ukraine,” VoxEU.org, 13 December.

Trebesch, C (2023), “Foreign support to Ukraine: Evidence from a database of military, financial, and humanitarian aid”, VoxEU.org, 21 February.