Financial innovation has long been a defining feature of the financial sector, in the shape of new products (e.g. new types of securities), new technologies (e.g. credit scoring, automated teller machines or ATMs), and new institutions (e.g. venture capitalists, mutual funds) (Tufano 2013). The current wave of financial innovation is being supported by specific technological advances, involving: smart phone technology, the internet and application programming interfaces (APIs); artificial intelligence (AI) and big data technology; and distributed ledger technology (DLT) (Allen et al. 2021). These new technologies affect the way banks produce and provide financial services to their customers, as well as bringing new fintech and big tech players into the production and provision of financial services. This has potential implications for incumbent financial institutions and, notably, for traditional banks. It might also create new sources of systemic risk, which could pose regulatory and policy challenges.

This column describes a recent report from the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB)’s Advisory Scientific Committee (Beck et al. 2022), which discusses the impact of digitalisation on Europe’s traditional banking system and the rise of new sources of risk stemming from digitalisation, and offers three different scenarios on how digitalisation will shape the future structure of Europe’s banking system.

A new wave of innovation

The recent wave of financial innovation based on the opportunities offered by digitalisation has come mostly from outside the incumbent banking system in the form of new financial service providers, either in competition or cooperation with incumbent banks but also with the potential for substantial disruption (Cornelli et al. 2020).

- Mobile phones (especially smart phones), the internet, and APIs have enabled quicker information exchange, new delivery channels, and better exploitation of economies of scale. This has allowed new delivery channels, a move away from the traditional brick-and-mortar branch models, and the entry of new payment service providers – from mobile phone companies offering mobile money to fintech companies offering digital wallets. The internet has also enabled more competition, allowing customers to compare products and prices of different financial services across providers, with platforms enabling customers to shift deposits across banks as conditions change.

- The information technology revolution, including the rise of cloud computing, has facilitated the creation, processing, and use of big data and applied statistics for measuring and managing financial risk. AI and machine learning enable an improvement in screening and monitoring models over existing techniques, such as traditional (mostly static) credit scoring models. Several studies have shown big data to be more useful in predicting default patterns than more traditional approaches, such as banks merely relying on credit registry data.1 AI and big data may also play a role beyond credit scoring in operational and broader risk measurement and management activities, such as fraud and cyber incident monitoring, anti-money laundering, and compliance checks.

- A third innovation is distributed ledger technology (DLT), which describes decentralised data architecture and cryptography and allows the keeping and sharing of records to be synchronised while ensuring their integrity through the use of consensus-based validation protocols. The most prominent DLT has been blockchain, based on Nakamoto (2008), who introduced it as a method of validating ownership of the cryptoasset bitcoin; it is a decentralised distributed database that maintains a continuously growing list of records locked into a chain of hacking-proof ‘blocks’. Although cryptoassets have caught the attention of many investors, there has been a trend towards stablecoins – cryptoassets that are pegged to another asset (such as the US dollar, other national currencies, and commodities) and whose value is guaranteed by holdings of sufficient reserves in these assets, similar in construction to a currency board. In addition (and reaction) to the increasing importance of private cryptoassetss, central banks around the world have started exploring the value of central bank digital currencies for retail customers (e.g. Bindseil et al. 2021).

Challenges for Europe’s banks

The European banking system is confronting fundamental structural changes and challenges that are going to shape its future and its ability to serve the financial needs of the real economy. Some of these challenges, including overbanking and non-performing loans (NPLs), have been present for several years and can be seen as legacy problems dating back to the global financial crisis and the European sovereign debt crisis. Other challenges are forward-looking in nature and relate to the changes affecting society beyond the banking and financial systems, such as climate change. In addition, the COVID-19 pandemic is affecting economic structures and exerting an impact on the banking system that may touch the core business models and operations of European banks.

Among the forward-looking challenges, the increased digitalisation of advanced economies appears to be quite relevant. For traditional banks, digitalisation may lead to offering new products and services, potentially improving customer experience.

New competitors for traditional banks

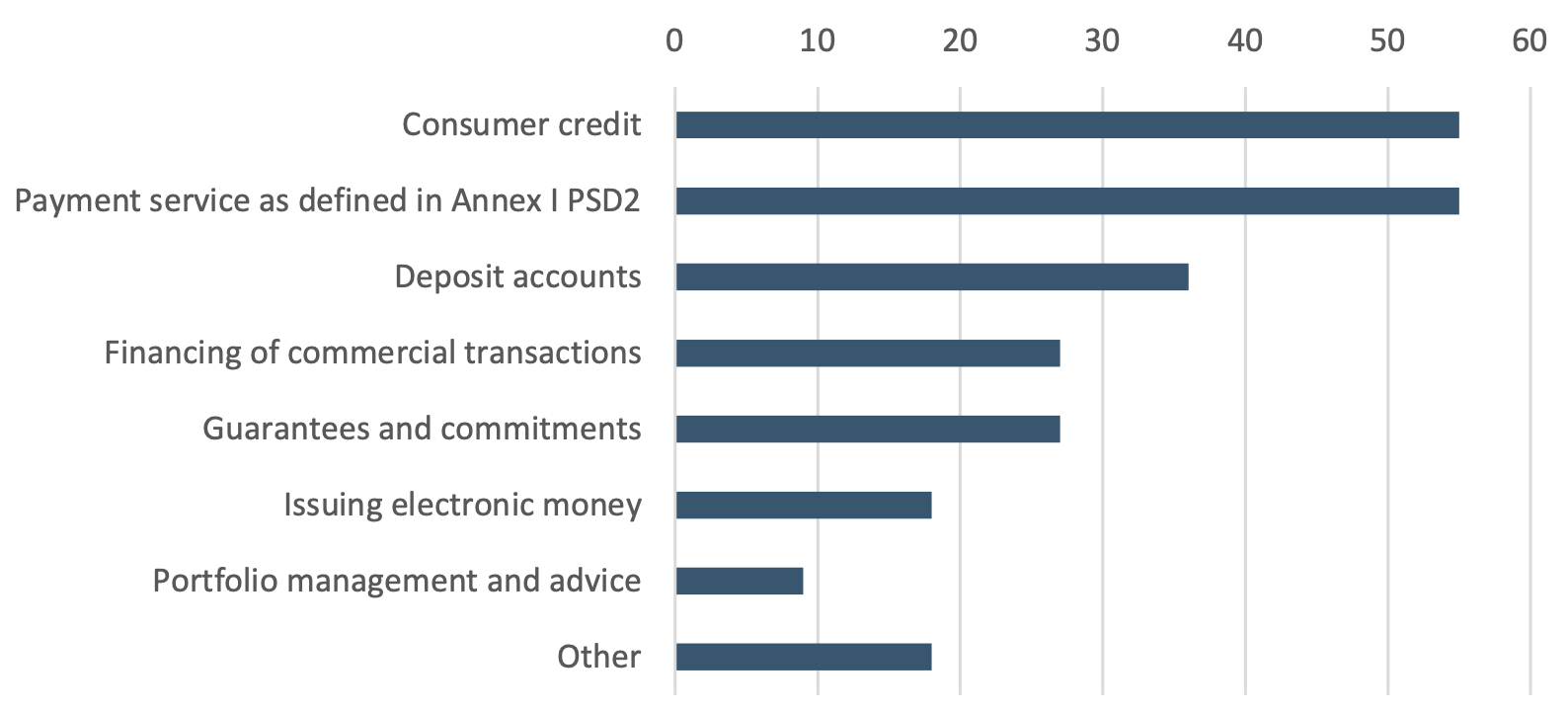

Across the globe, fintechs have shown impressive growth and are typically small and specialised in specific services (although, in aggregate, they cover a diverse group of financial services, Figure 1). Big techs, usually operating through platforms, derive advantages from data analytics, network externalities, and interwoven activities, and follow an envelopment strategy by moving from non-financial into financial services.2

As a result of these innovations and new providers, incumbent banks face competition across different business lines, and disintermediation may result in losses of scale and/or scope economies. Banks typically expect fintechs not to threaten their incumbency, albeit with some need to buy out innovators to sustain this position. With big techs, however, incumbent banks could react in different ways, depending on how big techs go about expanding into financial service provision: either by establishing subsidiaries or by cooperating with incumbent banks. The former approach would pose a direct challenge for incumbent banks, which might react by increasing their risk profile to defend their position. Cooperation seems less disruptive, although it would also likely erode the rents that incumbent banks have enjoyed so far, potentially rendering many of them unviable in their current business model.

Figure 1 Financial services marketed or distributed via a digital platform (% respondent financial institutions reporting use)

Source: European Banking Authority (2021).

New risks

New providers entering with bank-like intermediation models would be exposed to the known risks in banking (liquidity risk, credit risk, market risk, etc.), affecting, in turn, system-wide risk. While more competition could enhance stability over the long term, concentration (particularly with big techs) could result in new too-big-to-fail institutions, and a stronger focus on transaction-based intermediation could make the system more procyclical. Furthermore, incumbent banks may take greater risks to compete with new providers. Cooperation between big techs and incumbent banks might lengthen intermediation chains, moving them towards the originate-and-distribute model, which raises concerns about incentives and risk distribution.

In addition to financial risk, digitalisation also poses significant non-financial risks, both for banks and for fintech and big tech companies. These risks stem from several factors: greater concentration on providing basic services, such as cloud computing; broader use of artificial intelligence (AI) in finance; overly automated or IT-oriented services that may be more prone to cyberattacks; trust in a leading technology that might suddenly turn obsolete; and a false sense of security from overleveraging insights from AI.

Three scenarios for European banking in 2030

The contribution of financial and non-financial risks to the overall level of risk in the system depends on how incumbent banks interact with fintechs and big techs in the future, an area still dominated by uncertainty. Consequently, the report uses three alternative scenarios for the EU financial system in 2030 as a basis for discussing the appropriate macroprudential policy responses. The three scenarios do not cover every possible path of the EU banking system until 2030, but were selected on the basis of their implications for the interaction of banks with fintechs and big techs (scenarios 1 and 2) and the impact of central bank digital currencies (scenario 3).

- Scenario 1: Incumbent banks continue to dominate and maintain their central role in money creation and financial intermediation. They aggressively counter the competitive threat through technological adaptation, acquiring fintech companies, and lobbying. Fintechs continue to focus on specific niche markets, while big techs offer payment services but do not have access to central bank clearance and payment systems (they might cooperate with incumbent banks). The banking system renews itself by incorporating new providers and new products.

- Scenario 2: Incumbent banks retrench, while big techs offer financial services through regulated subsidiaries and capture the hard-data, transaction-based lending market. Incumbent banks increasingly focus on relationship-intensive services, at both the high end (investment banks) and low end (community banks) of the market. The banking system shrinks, especially because mid- and small-sized banks are no longer able to exploit scope economies. This scenario leads to a structural change in the financial system.

- Scenario 3: Issuance of retail central bank digital currencies, under certain intermediation models, leads to a very different structure of the financial system. Incumbent banks face higher funding costs and a more volatile funding base, as the traditionally stable retail deposit clientele switches, at least partially, to the digital currency. Financial intermediation moves away from incumbent banks, while the central bank plays an increasing role as an intermediary. Other financial service providers (including fintechs and big techs) offer tailormade and specialised services in lending, asset management, and risk management. The traditional banking system no longer plays the role of a stable anchor.

Policy conclusions

Given that developments in the financial system are endogenous to regulatory responses and adjustments, especially during potentially disruptive transformations, we propose several policy actions to address financial and non-financial risks. Some of these actions would apply to all three scenarios, while others would be more relevant if only one of the three scenarios materialises. Critically, the regulatory response will be a key driver of which of the three scenarios materialises.

These policy actions are the following:

- The regulatory perimeter and conditions for accessing the safety net would need to be expanded or adapted. Fintechs and big techs would need to have access to the safety net in case of performing bank-like financial activities. At the same time, a prudential framework should be developed, including consumer protection and anti-money laundering. This becomes even more important in the scenarios of bank retrenchment and central bank digital currencies.

- Global cooperation may need to be enhanced further, since most fintech and big tech companies operate on a global scale, with no permanent establishment in jurisdictions where they are present. To avoid undesired and untimely discussions, mechanisms for cooperation should be put in place ex ante.

- The financial intermediation activities of big techs may need to be ring-fenced and therefore provided through a subsidiary that falls within the regulatory perimeter. This policy may require profound organisational changes in big techs and might reduce the appeal of entering the financial intermediation business, greatly decreasing the probability of the second scenario (banks’ retrenchment).

- The extended use of non-financial providers of services may fall under a different regulatory authority (e.g. telecom regulator) and require enhanced cooperation between regulators in different sectors and jurisdictions. Such cooperation might also be required across borders, given the global nature of most big techs. As the regulatory and legislative approaches towards platform companies (i.e. big techs) change at the EU level, such changes should involve close cooperation with financial-sector regulators.

- Increased digitalisation in financial services may require a change in regulatory and supervisory practices, which were defined when digitalisation was in its infancy and non-financial risks were not high priorities on the regulatory agenda. Digitalisation may increase the importance of non-financial risks (many of them currently under the umbrella of operational risks), and a more accurate reflection of these risks in the prudential framework may be required. This would also apply to the skills of staff in regulatory and supervisory authorities.

- Political decisions on the issuance of central bank digital currencies to retail customers would need to carefully balance efficiency gains against any stability risks posed to the incumbent financial system. Issuing digital currencies can give customers more options and result in more competition. However, it is important to consider the medium- to long-term implications for the structure of the financial system, in terms of both efficiency and stability.

- The support framework for an orderly exit and capacity reduction of incumbent banks should be strengthened: under every scenario, they will face increased competition and even tighter profit margins. This will necessarily result in incumbent banks reducing capacity and possibly exiting the market, a process that can cause fragility. This process can also be proactively facilitated by avoiding government support for unviable banks, facilitating mergers, easing barriers to market exit and liquidation, and completing the banking union.

References

Allen, F X G and J Jagtiani (2021), “A Survey of Fintech Research and Policy Discussion”, Review of Corporate Finance 1, 259–339.

Beck, T, S Cecchetti, M Grothe, M Kemp, L Pelizzon and A Sánchez Serrano (2022), Will video kill the radio star? Digitalisation and the future of banking, Reports of the ESRB Advisory Scientific Committee No. 12, January.

Berg, T, V Burg, A Gombović and M Puri (2020), “On the Rise of FinTechs: Credit Scoring Using Digital Footprints”, Review of Financial Studies 33, 2845–2897.

Bindseil, U, F Panetta and I Terol (2021), “Central Bank Digital Currency: functional scope, pricing and controls”, ECB Occasional Paper Series No. 286, December.

Björkegren, D. and Grissen, D. (2020), “Behavior Revealed in Mobile Phone Usage Predicts Credit Repayment”, The World Bank Economic Review 34, 618–634.

Cornelli, G, J Frost, L Gambacorta, R Rau, R Wardrop and T Ziegler (2020), "Fintech and big tech credit: a new database", BIS Working Paper 887 (also published as CEPR Discussion Paper 15357).

European Banking Authority (2021), “Report on the use of digital platforms in the EU banking and payments sector”, September.

Frost, J, L Gambacorta, Y Huang, H S Shin and P Zbinden (2019), “BigTech and the changing structure of financial intermediation”, Economic Policy 34, 761–799.

Jagtiani, J and C Lemieux (2018), “The roles of alternative data and machine learning in fintech lending: Evidence from the LendingClub consumer platform”, Financial Management 48, 1009–1029.

Nakamoto, S (2008), “Bitcoin: a peer-to-peer electronic cash system”, mimeo.

Tufano, P (2003), “Financial innovation: the last 200 years and the next”, in The Handbook of the Economics of Finance, JAI Press.

Endnotes

1 See, for example, Björkegren and Grissen (2020) on mobile phone call records; Berg et al. (2020) on ‘digital footprint’ data used by a German e-commerce company; Frost et al. (2019) on data from Mercado Libre in Argentina, an e-commerce platform; and Jagtiani and Lemieux (2018) comparing loans made by a large fintech lender to similar loans originated by traditional banks.

2 While there is no one widely accepted definition of either, we define fintech firms as new technology-driven players aiming to compete with traditional financial institutions in the delivery of financial services and big tech firms as platform firms, such as Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Alibaba, and Tencent.