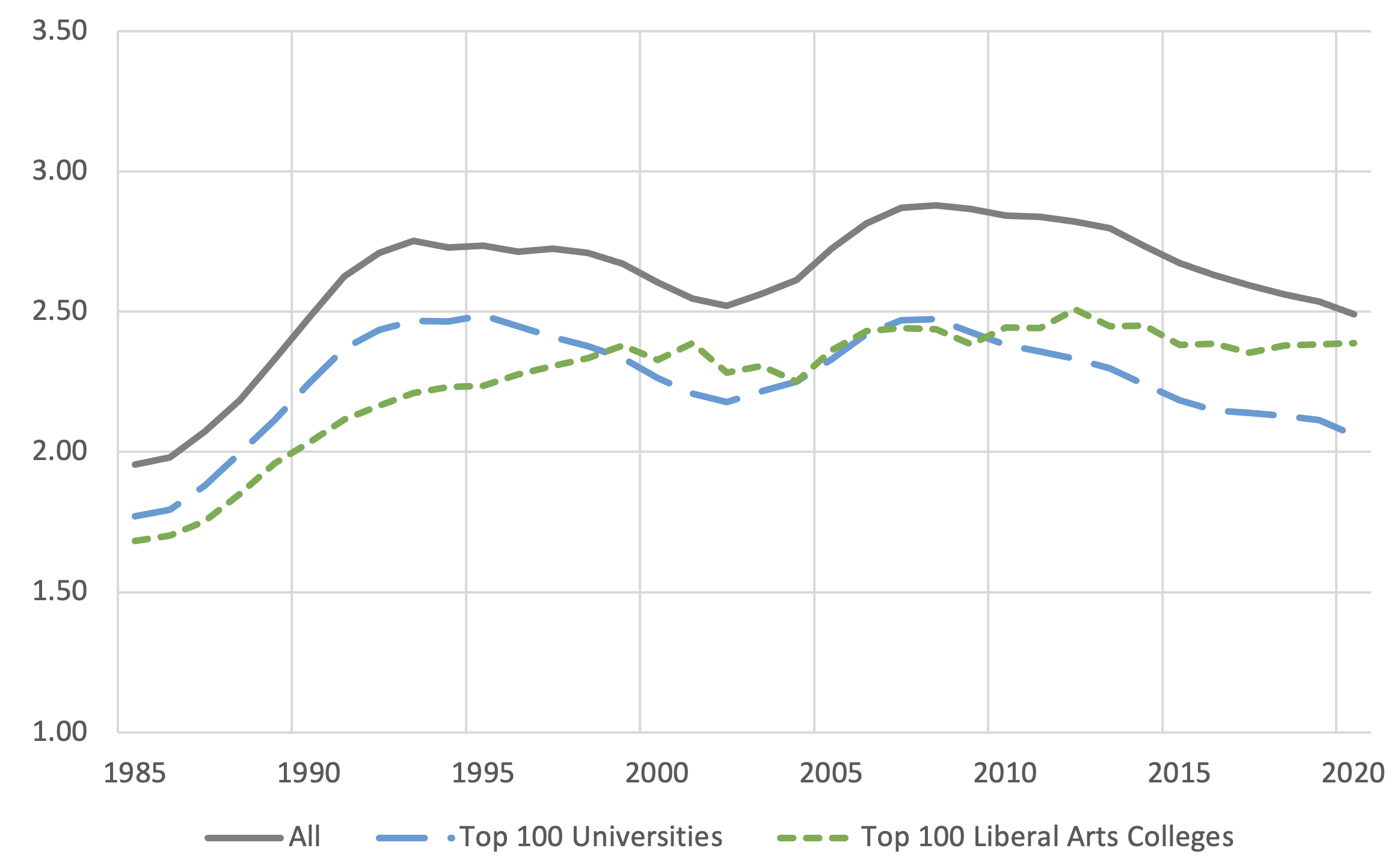

Economics has long been among the most popular and highly remunerative undergraduate majors. But women do not major in economics to the same degree as do men. The good news is that there are relatively more female economics majors now than 20 years ago, even scaled by their numbers as bachelor’s degree (BA) recipients (women earn far more BAs than do men). The bad news is that the gain has merely brought us back to levels achieved around 1992 (see Figure 1). The fraction of women among majors in economics remains lower than in many STEM fields (Bayer and Rouse 2016).

Several years ago, we initiated the Undergraduate Women in Economics (UWE) Challenge, a one year randomised controlled trial (RCT) with the purpose of narrowing the gender gap in economics.

Now that many of the undergraduate cohorts treated by the interventions have graduated, we can evaluate our light-touch, low-cost programme.

The bottom line is that UWE (pronounced “you”) was effective in increasing the fraction of female BAs who majored in economics relative to men in liberal arts colleges. Large universities did not show an impact of the treatment. The sheer size of these institutions meant that the light-touch interventions could not reach enough undergraduates. In some cases, enrollment capacity limitations and constraints on the number of faculty and teaching staff may have deterred departments from recruiting more students. However, among the large universities, those that implemented their own UWE RCTs showed modest success in encouraging more women to major in economics (even if some of their own institutional RCTs showed limited impact).

The gender gap in economics

Our measure of the gender gap in economics and its change over time must consider the fact that women now receive considerably more bachelor’s degrees than do men. We employ various forms of a statistic we term the ‘conversion ratio’. The conversion ratio gives the extent to which male or all (female and male) undergraduates opt into the economics major relative to female undergraduates. The ratio is scaled by the number of degree recipients, showing the extent to which male or total versus female undergraduates get ‘converted’ into economics majors.

We use the male to female economics major version in our discussion of general trends when the unit of analysis is a group of institutions (or the entire US). When each school is the unit of observation, we use the variant that gives the ratio of female economics majors to total economics majors (scaled by the fraction female among all BAs) because it is less sensitive to the fact that some institutions have very few female majors. Schools have increasingly allowed students to have multiple majors, and we have included in the analysis dual majors after 2001 when the NCES IPEDS reports those data.

We plot in Figure 1 the conversion ratio [(M econ/F econ)/(M BA/F BA)] among all undergraduate institutions in the US that had an economics major. Information is provided for the top 100 universities and top 100 liberal arts colleges, as well as for all institutions with an economics major. In the most recent years, the number of male to female economics majors (adjusted for BAs) was around 2.5 across all institutions, 2.4 for liberal arts colleges, and 2.1 for top universities.

Figure 1 Economics conversion ratios (male economics majors/female economics majors)/(male BAs/female BAs), 1984 to 2021

Notes: The conversion ratio is the ratio of male to female economics majors divided by the ratio of male to female BAs across all institutions in each of the three groups. Therefore it is a national average for these institutions. Data for multiple majors begins in 2001 but those for a single major do not yield results that are much different. Inclusion of the “second” major generally decreases the “conversion” ratio since relatively more women have economics as a “second” major. -year centered moving averages shown. “Top 100” institution lists are from the 2013 US News and World Report. “All” is for the entire US. Schools are included only if they granted an undergraduate degree in economics. Economics includes all fields under NCES CIP code 45.06.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics, IPEDS online.

There are several reasons to be concerned that women are underrepresented in economics. Most important is that some of the gender gap is due to incorrect or misperceived information about the major and career options. A common misperception is that economics is only about finance. This view often dissuades women from majoring in economics, at the same time as it encourages men to do so. Another reason is that a large earnings premium exists among economics majors (Stange et al. 2022). Finally, gender imbalances change the nature of economics since women and men gravitate to different fields within economics.

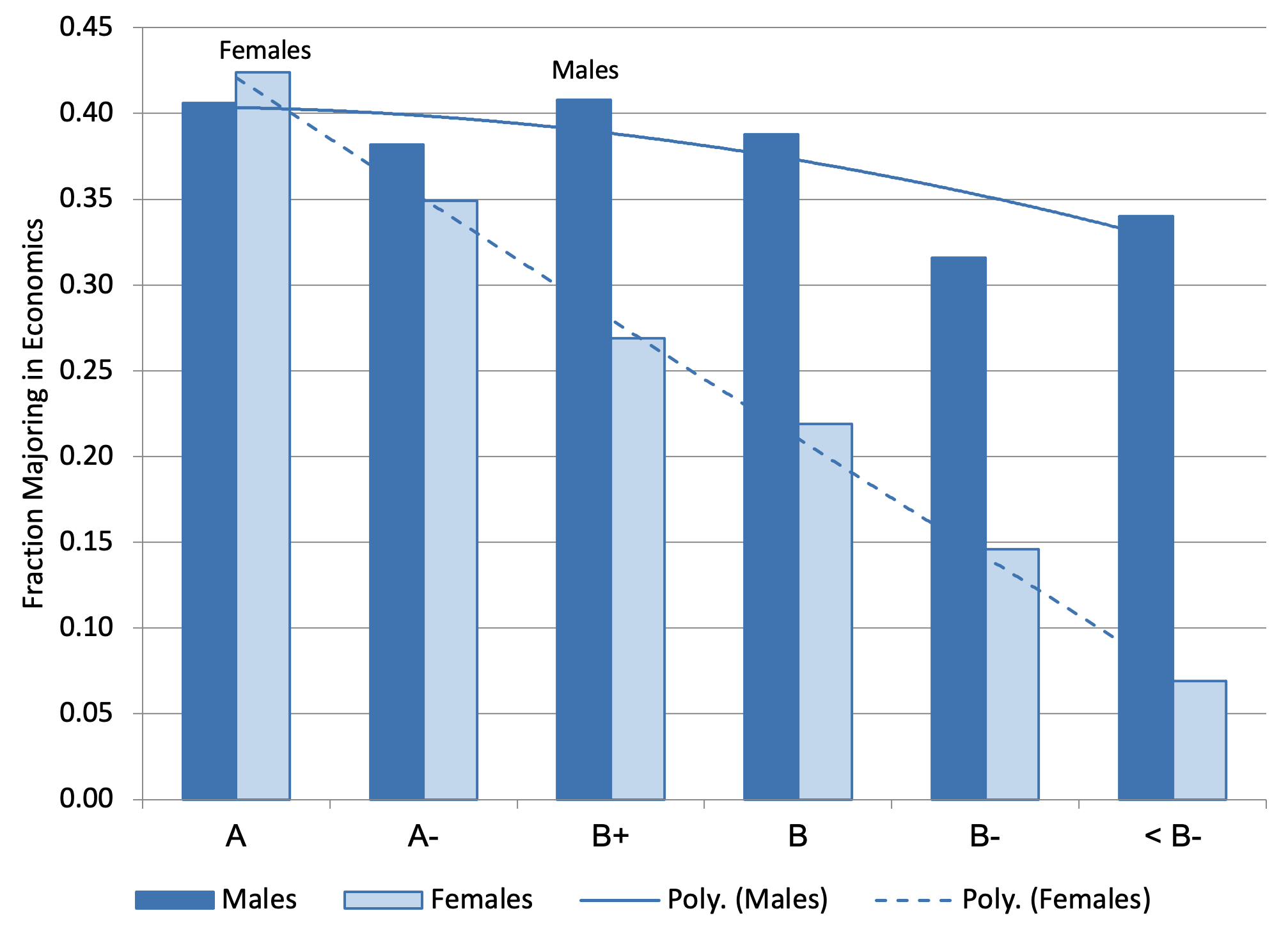

Women’s greater grade sensitivity is another factor that has led many to exit the field after taking the Principles sequence even when they received the same grades as men who remain with the major. Figure 2 shows that women who took Principles at “Adams College” (a fictitious name for a real institution that provided the authors with administrative data for several classes graduating before 2014) had a much higher probability of majoring in the subject if they obtained an exceptional grade. Men, however, majored in economics almost regardless of their grade in Principles. Therefore, women have greater ‘grade sensitivity’ regarding their likelihood of majoring in economics.

Figure 2 Fraction majoring in economics by grade in Principles at “Adams College”, c. 2012

Notes: Grade is for Principles-Spring or -Fall if the student placed out of Principles-Spring. Results do not change if only Principles-Fall is used. Trend-lines are second degree polynomials.

Sources: “Adams College” administrative data.

Creating the UWE Challenge

In the summer of 2014, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation generously funded a grant through the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) that enabled the implementation of an RCT, later titled the Undergraduate Women in Economics (UWE) Challenge.

In January 2015, UWE sent emails to the economics department chairs (or undergraduate programme coordinators) of all US colleges and universities with a reasonably sized economics programme, asking if the department was willing to implement a set of interventions intended to increase the number of female majors. They were told that they would be given $12,500 if they were selected and that the funds could be used in any reasonable way to implement the suggested (or similar) light-touch interventions. The sizable number of affirmative replies allowed the sample to be further limited to 88 schools that had a substantial aggregate number of economics majors. Of those, 20 were randomly chosen as treatments and the remaining 68 became controls.

The 20 treatment schools were deliberately chosen in a manner to be highly varied. Some are large state universities, a few are flagship institutions, some are small liberal arts colleges, and several are Ivy League institutions. During the 2015/16 academic year, treatment institutions used the funding and guidance from the project organisers to propose and initiate interventions that would disproportionately increase the number of female economics majors, possibly without decreasing the number of male economics majors. One size would not fit all the UWE treatment institutions, and a list of potential light-touch interventions in the following three areas were assembled: (1) better information; (2) mentoring and role models; and (3) instructional content and pedagogical style.

What UWE did

We used the NCES IPEDS data to explore whether the 20 treated schools had outcomes at graduation different from those of the 68 control schools for treated cohorts (Avilova and Goldin 2023). The dependent variable is the conversion ratio for female majors relative to all majors in each year for each institution scaled by the ratio of BAs [(F econ/Total econ)/(F BA/Total BA)]. The estimation is a relatively standard difference-in-differences analysis where the post-treatment period is taken to be all years from the academic year 2017/18 to 2020/21 and the full period begins with 2000/01.

Our main finding is that a treatment effect of the UWE intervention is discernable and substantial for the liberal arts colleges but not for the entire group of treatment schools. The impact for the liberal arts college is 17% of the mean for the dependent variable.

The reasons for a differential impact by type of institution are several. The liberal arts colleges were actively involved in multiple interventions. Several of the larger institutions (whether public or private) struggled to get faculty buy-in despite the enthusiasm of the faculty and staff directly involved in the UWE Challenge. Most faculty supported increased diversity in economics and participated in one-time interventions but were less enthusiastic about those that demanded continued commitment. The higher faculty-student ratio at the liberal arts colleges may have been an additional factor.

There are ample reasons why the light-touch interventions would have reached too few undergraduates at some of the larger institutions. But six of the larger treatment universities did their own RCTs and evaluated them using administrative records from the schools (for which they each obtained their own IRB). Despite their size, the deliberate implementation of experimental treatments and the presence of invested faculty may have enhanced the effect of the UWE treatment.

Conclusion

The Undergraduate Women in Economics Challenge tested whether deliberate efforts could move the needle on female representation among undergraduate economics majors. We find that interventions at treatment schools may have been successful at liberal arts colleges and possibly at the larger universities that, in addition, had their own RCT.

The interventions that our treatment schools used were low-cost and light-touch. But they required the time and initiative of undergraduate instructional staff and faculty. The UWE programme provided advice and funding and gave recognition to these hard-working faculty and teaching staff. We should note that the UWE Challenge sparked many non-treatment economics departments to be less complacent in their general success in appealing mainly to male students. If our efforts have led to greater awareness that curriculum and advising should be altered to also attract the majority BA group – women – we will have succeeded admirably.

Authors’ note: The authors thank the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation for funding and Danny Goroff for encouragement. We are grateful to faculty members at the UWE treatment schools and the members of the UWE Board of Experts who helped set up the UWE Challenge.

References

Antman, F, E Skoy, and N E Flores (2022), “Can better information reduce college gender gaps? The impact of relative grade signals on academic outcomes for students in introductory economics”, working paper, University of Colorado, Boulder.

Avilova, T and C Goldin (2023), “What did UWE do for economics?”, NBER Working Paper no. 31432.

Avilova, T and C Goldin (2020), “What can UWE do for economics?”, in S Lundberg (ed.) Women in Economics, CEPR Press, pp. 43-50.

Avilova, T and C Goldin. (2018), “What can UWE do for economics?”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 108: 186-90.

Bayer, A, and C E Rouse (2016), “Diversity in the economics profession: A new attack on an old problem”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 30(4): 221–42.

Bedard, K, J Dodd, and S Lundberg (2021), “Can positive feedback encourage female and minority undergraduates into economics?”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 111: 128-32.

Bozzano, M and G Bertocchi (2020), “The education gender gap: From basic literacy to college major”, VoxEU.org, 5 October.

Butcher, K, P McEwan, and A Weerapana (2023), “Women’s colleges and economics major choice: Evidence from Wellesley College applicants”, VoxEU.org, 6 Aug.

Goldin, C (2015), “Gender and the undergraduate economics major: Notes on the undergraduate economics major at a highly selective liberal arts college”, working paper, Harvard University.

Halim, D, E T Powers, and R Thornton (2022), “Gender differences in economics course-taking and majoring: Findings from an RCT”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 112: 597-602.

Li, H-H (2018), “Do mentoring, information, and nudge reduce the gender gap in Economics majors?”, Economics of Education Review 64: 165-83.

Lundberg, S (2020), “Women in the economics profession: A new eBook”, VoxEU.org, 5 March.

Patnaik, A, G C Pauley, J Venator, and M J Wiswall (2023), “The impacts of same and opposite gender alumni speakers on interest in economics”, NBER Working Paper No. 30983.

Porter, C, and D Serra (2020), “Gender differences in the choice of major: The importance of female role models”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 12(3): 226-54.

Stange, K, S A Imberman, M F Lovenheim, and R Andrews (2022), “College majors affect more than just average earnings”, VoxEU.org, 27 October.