After years of being sidelined in European policy debates against the backdrop of labour markets recovering from the Great Recession, inequality is back on the agenda following the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing cost-of-living crisis. While some empirical analysis conducted before the pandemic provided a picture of growing income inequality in most European countries (see Blanchet et al. 2019 for trends between 1980 and 2017), others noted a more nuanced picture across rich countries (Nolan 2018, Kanbur 2020). More recently, inequality was predicted to increase further in the aftermath of the pandemic (Alfani 2020, Pizzuto et al. 2020).

Beyond trends across countries, a relevant strand of the empirical literature focuses on estimating inequality from a global perspective (Milanovic 2005). These studies identify a fall in global income inequality levels due to narrowing disparities in income levels between nations, while within-country inequalities have grown in most developed countries in recent decades (Ortiz-Juarez et al. 2022, Wills and Mayhew 2020, Milanovic 2016), although other studies proposing new methods claim this within-country inequality has stopped rising and started falling in recent years (Maxim Pinkovskiy et al. 2024). This approach has been used less often to estimate income inequality in supranational entities such as the EU, but the existing analyses point to declining inequality levels due to income convergence between EU countries (Fischer and Filauro 2021).

In a recent report (Vacas Soriano 2024), I use household disposable income data from the Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) over the period 2007–2022 to provide an updated picture on income inequality and middle-class populations across EU27 countries.

EU-wide income inequality declined due to income convergence between countries

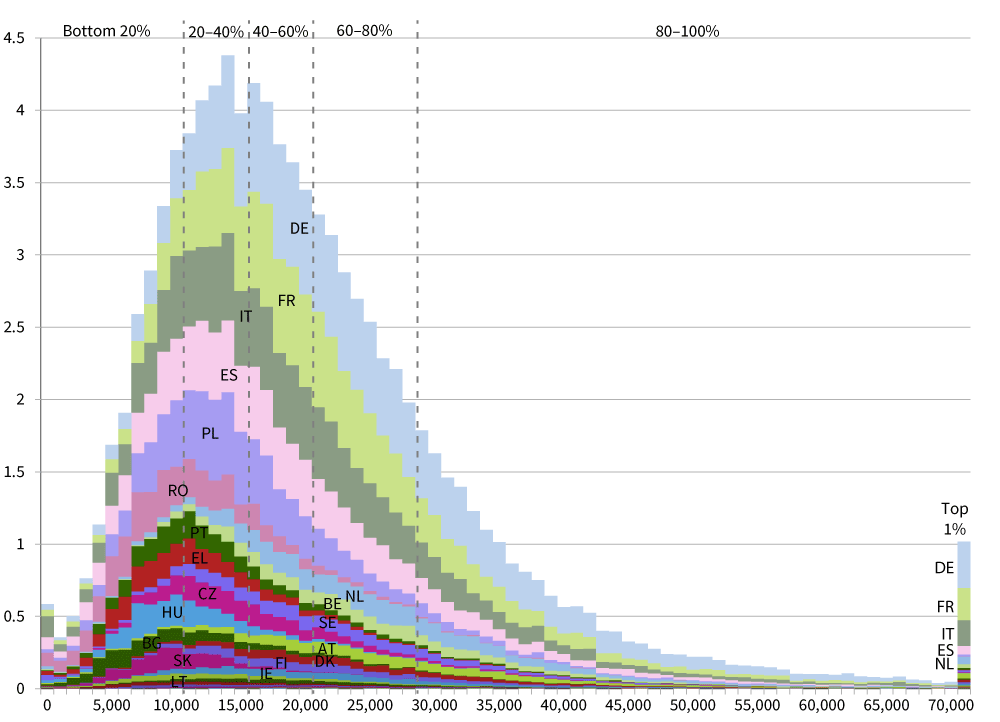

Measuring income inequality for the EU as a whole requires considering all EU citizens as part of a single income distribution (shown in the top panel of Figure 1), which is shaped by income disparities both between and within countries. Two insights emerge. First, income disparities between countries are reflected by the different positions they occupy in the EU-wide income distribution: populations of member states that joined the EU after the 2004 enlargement (EU13) are relatively more represented at the bottom EU-wide income quintile, while the populations of older member states (EU14) account for almost all people found in the top quintile. Second, income disparities within countries are evidenced by the significant overlapping of different countries, especially the largest, whose populations are spread over the EU-wide income distribution.

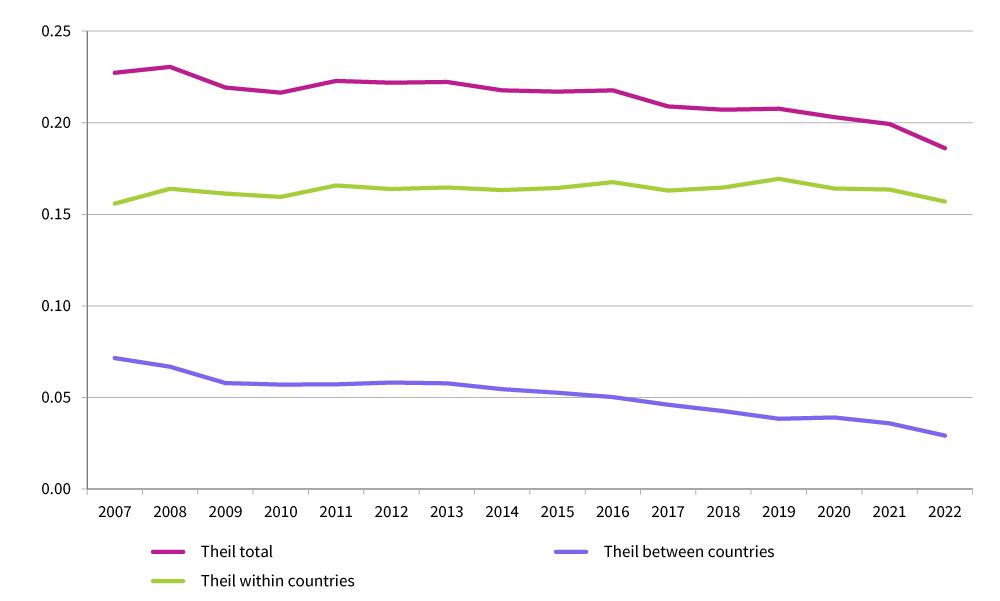

Income inequality for the EU aggregate can be decomposed into those two elements (between and within-country income disparities) by using the Theil index (see the bottom panel of Figure 1). A picture of declining EU-wide inequality emerges between 2007 and 2022 (given the one-year lag in EU-SILC income data, it really refers to 2006–2021) and reverses during the Great Recession and its aftermath before resuming thereafter and continuing even in the most recent years of the COVID-19 pandemic. The contribution of between and within-country income disparities plays a very different role. On the one hand, the reduction of income disparities between countries are entirely responsible for the fall of EU-wide income inequality in the last 15 years. This is explained by a strong process of convergence in average income levels between countries, largely due to catch-up income growth in most EU13 countries and much more modest progress in EU14 countries.

On the other hand, within-country income disparities represent the lion’s share of EU-wide income inequality levels (and increasingly so, given the abovementioned reduction in income disparities between countries), but they did not play a significant role in the evolution of EU-wide income inequality because they were broadly similar at the beginning and the end of the period.

Figure 1 EU-wide income inequality

a) Shares of EU population by equivalised household disposable income level in PPP-euro in 2022

b) Evolution of inequality levels as measured by the Theil index

Notes: Data on equivalised household disposable income is made comparable across EU countries by using euros adjusted by purchasing power parity (PPP). The EU-wide income distribution (including those aged at least 16) is split into five income quintiles by the vertical lines (upper panel).

Source: EU-SILC 2022 edition (income referring to 2021) for the upper panel; EU-SILC 2007–2022 editions (income referring to 2006–2021) for the bottom panel.

Evolution of income inequality in EU countries: A mixed picture

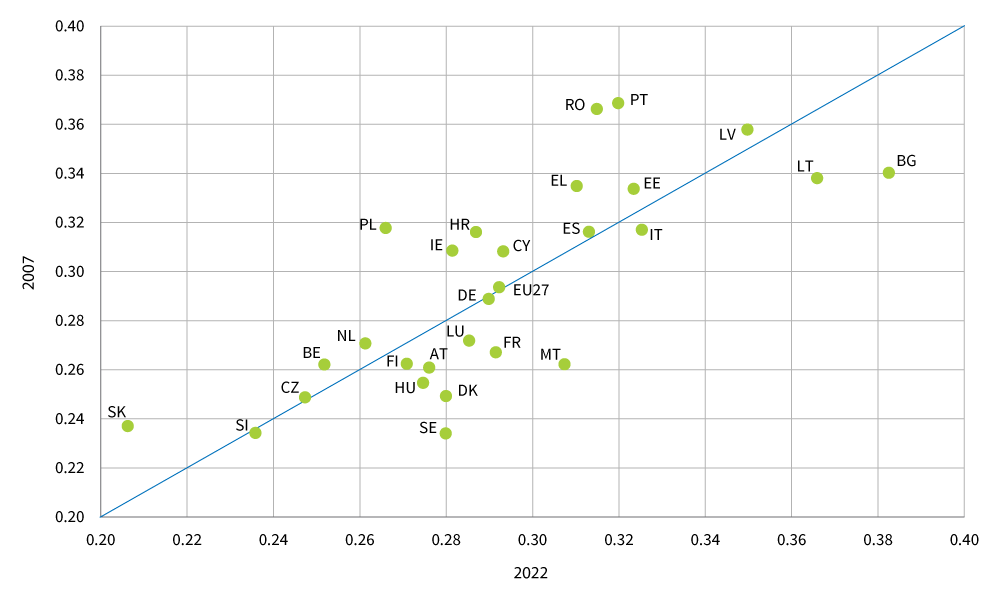

The relative stability of aggregate within-country income inequalities conceals the existence of diverging patterns across countries, captured by comparing inequality levels at the beginning and the end of the period (see Figure 2). The picture is mixed: inequality increased in around half of countries (the 13 countries below the diagonal line in the figure), especially so in Sweden, Denmark, Malta, and Bulgaria; while inequality declined in the other half (the 14 countries above the diagonal line), significantly so in Poland, Romania, Portugal, and Slovakia.

A certain convergence in income inequality levels between countries has taken place over the period. Among those countries initially characterised by relatively low inequality levels, a rather consistent upwards trend emerged in several EU14 countries from the Nordic region (Sweden, Denmark, and Finland) and continental clusters (Austria, Luxembourg, and France), plus Malta and Hungary. Among countries initially characterised by relatively high inequality levels, a moderation occurred in several EU13 countries (Romania, Poland, Croatia, Latvia, Estonia, Cyprus), plus Portugal, Greece, and Ireland. These diverging trends have shaken-up the position of some countries on the inequality scale: Sweden and Denmark have become relatively more unequal, Poland much more equal.

Figure 2 Diverging cross-country patterns in income inequality, 2007 and 2022 (Gini index)

Notes: Income inequality levels are measured by the Gini index (ranging from values of 0 to 1).

Source: EU-SILC 2007 and 2022 editions (income referring to 2006 and 2021).

Evolution of the middle class in EU countries: Shrinking in most cases

European countries are middle-class societies where a majority of people belongs to this class (here defined as those with an equivalised household disposable income between 75% and 200% of the national median). On average across EU27 countries, the middle-income class comprises 64% of the population (while 28.5% and 7.5% belong to the lower and the higher income class, respectively), ranging from above 75% in Slovakia to 51% in Bulgaria. This makes for cohesive societies with a large proportion of people concentrated around the middle of the income distribution, which explains why the size of the middle class and income inequality levels are very correlated.

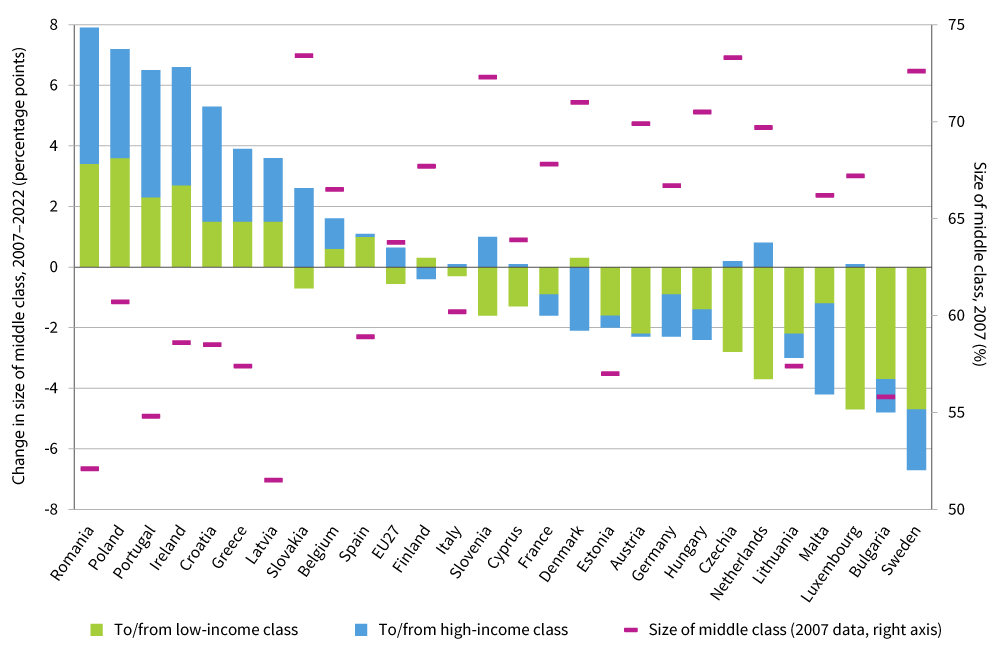

Changes in the size of the middle class and in income inequality are also very correlated, but a more generalised picture across EU countries emerges in this case. While the cross-country average size of the middle class has remained broadly stable over the period (contracting negligibly from 64% to 63.8%), a shrinking emerges in almost two-thirds of countries (see Figure 3). The contraction was more significant in those countries to the right of the figure (they are ranked from a larger increase to a larger decline in the size of the middle class over the period), a mix of EU14 (especially Sweden and Luxembourg, but also the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Denmark) and EU13 countries (especially Bulgaria and Malta, but also Lithuania, Czechia, Hungary, and Estonia). Conversely, the middle class expanded in ten countries (to the left of the figure), very significantly in some EU13 countries (Romania, Poland, and Croatia), as well as in Portugal and Ireland.

The figure offers two more insights. First, the generalised shrinking of the middle class translated more prevalently in a downward movement of people into the lower-income class. Second, a certain convergence in the size of the middle class has taken place between countries as well, due to its contraction in some countries where it was very large initially, and its expansion in other countries where it used to be smaller (for instance, Sweden, Denmark, Netherlands, or Czechia in the former case; Romania, Latvia, or Portugal in the latter).

Figure 3 The middle class shrank in most countries (change in the size of the middle class, 2007–2022, in percentage points)

Notes: Data depict changes in the size of the middle class, differentiating between people coming from low- and high-income classes in cases of increases in the middle class, or moving into low- and high-income classes in cases of declines in the middle class. For this reason, the sign of the changes in the size of the low- and high-income classes has been inverted. Countries are ranked by the change in the size of the middle class, from biggest increase to largest decline. “EU-av” refers to the unweighted average across EU27 countries.

Source: EU-SILC 2007–2022 editions (income referring to 2006–2021).

Concluding remarks

This column summarises trends in income disparities within the EU over the last 15 years for which data are available. It shows that EU-wide income inequality declined due to a strong process of income convergence between countries, largely due to notable catch-up growth in EU13 countries. Against the well-established public perception of growing income inequalities and shrinking middle classes, it shows that income inequality increased in only around half of EU27 countries, while the middle class shrank in almost two-thirds of these countries, although to varying degrees.

When putting these findings together, a nuanced picture of different patterns across European regions emerges. The most positive picture is among EU13 countries: most showed strong income growth, and several managed to become less unequal and expand their middle classes (Romania, Poland, Croatia, Slovakia, and Latvia). A bleaker dynamic characterises EU14 countries: many of them registered growing inequalities and shrinking middle classes (the three Scandinavians and Austria, Germany, France, and Luxembourg among the continental cluster); and in the Mediterranean countries (Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain) where this did not occur (except in Italy), narrowing disparities took place against a background of poor income growth, which prevented a significant convergence of these countries towards higher income levels.

Due to the opposing trends affecting different groups of countries, a certain process of convergence between EU countries has occurred. This process has occurred as well in income inequality levels and the size of the middle class, although less intensely than in income levels.

References

Alfani, G (2020), “Pandemics and inequality: A historical overview”, VoxEU.org, 15 October.

Blanchet, T, L Chancel and A Gethin (2019), “How unequal is Europe? Evidence from distributional national accounts”, WID.world Working Paper 2019/6.

Fischer, G and S Filauro (2021), “Income inequality in the EU: General trends and policy implications”, VoxEU.org, 17 April.

Kanbur, R (2020), “An age of rising inequality? No, but yes”, VoxEU.org, 21 September.

Milanovic, B (2005), Worlds Apart: Measuring International and Global Inequality, Princeton University Press.

Milanovic, B (2016), Global Inequality: A New Approach for the Age of Globalization, Harvard University Press.

Nolan, B (2018), “Inequality and ordinary living standards in rich countries”, VoxEU.org, 3 August.

Ortiz-Juarez, E, A Summer and R Kanbur (2022), “The global inequality boomerang”, VoxEU.org, 2 May.

Pinkovskiy, M, X Sala-i-Martin, K Chatterji-Len and W Nober (2024), “Inequality within countries is falling”, VoxEU.org, 19 August.

Pizzuto, P, P Loungani, J D Ostry and D Furceri (2020), “COVID-19 will raise inequality if past pandemics are a guide”, VoxEU.org, 8 May.

Vacas Soriano, C (2024), “Developments in income inequality and the middle class in the EU”, Eurofound, 12 July.

Wills, S and K Mayhew (2020), “Inequality: What has happened, why care, and what can be done about it”, VoxEU.org, 18 June.