Much popular discussion now regards an increase in government borrowing (‘unfunded tax cuts’) as a very risky endeavour. By way of example, a recent front page report in the Financial Times on market worries associated with a prospective rise in borrowing quotes a market participant as saying that the Truss episode was still “etched into the psyche” of gilt investors (Financial Times 2024).

Recall that the trough-to-peak move in ten-year gilt yields during that period was as much as 293 basis points!

In this column, I consider a variety of different reasons for why UK yields might have risen during the ‘Truss period’ and show that the popular view might overstate the impact of higher borrowing. The analysis suggests that the projected increase in borrowing plausibly accounted for less than one-quarter of the observed rise in gilt yields during this period. I also discuss some implications of these findings for the plausible market impact of the UK government modifying its fiscal rules as a part of its forthcoming Budget on 30 October.

Some plausible reasons why yields rose

There are several possible explanations for why yields might have risen over this period. In order to attempt to tease out their relative contribution, it is very important to be cognizant of the Bank of England’s intervention in the gilts market that was announced on 28 September 2022 (Bank of England 2022). For that reason, the quantitative analysis below mainly stops on the day before (27 September).

(i) Global yields

Of course, gilt yields are influenced by global bond yields as they compete for global capital. For a variety of reasons, yields in several developed countries rose meaningfully during this period. Table 1 displays the rise in ten-year yields in some key comparator countries during the trough-to-peak rise in UK yields by 27 September.

Table 1 The rise in international ten-year yields between 2 August and 27 September 2022

With international yields rising by about 150 basis points over this period, it would appear that the UK-specific component of the actual rise in UK gilt yields is only around one-half of it. Incidentally, it is interesting to note that the low in yields over this period was on 2 August in all three countries, which merely serves to emphasise the importance of global factors.

(ii) A questioning of the institutional framework

A feature of the now infamous Budget statement on 23 September 2022 was that the government chose not to commission a forecast from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). Moreover, there was market chatter about the possibility that the Bank of England’s remit might be modified to a nominal GDP target, which might amount to an implicit upward revision in the inflation target.

That this might have been an important feature during the Truss episode is, perhaps, consistent with how other markets behaved over this period. Textbook models usually show fiscal expansions leading to an exchange rate appreciation. Typically, in developed countries, as long as markets believe that the central bank will continue to be able and willing to achieve its inflation target (i.e. in the absence of so-called fiscal dominance), the textbook model works and the exchange rate does appreciate and longer-term inflation expectations remain stable.

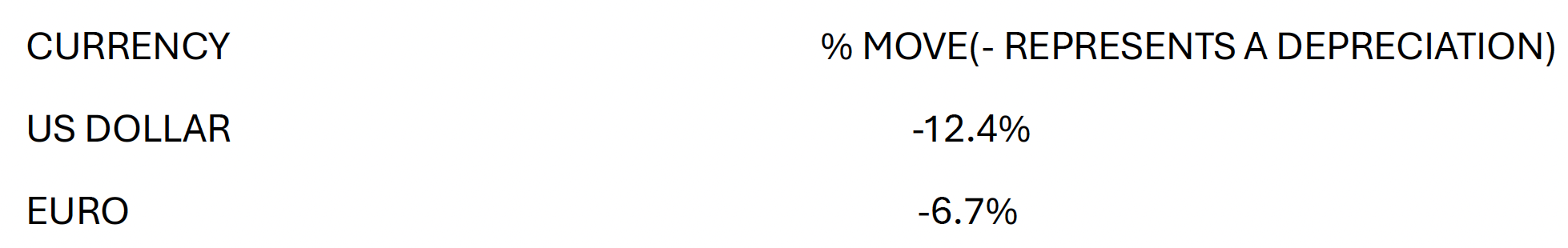

Table 2 shows movements in the exchange rate between 2 August and 27 September.

Table 2 Percentage change in the sterling exchange rate versus other currencies between 2 August 2 and 27 September

Specifically, sterling depreciated meaningfully versus both the US dollar and the euro. Note that the extent of depreciation was even greater at the lows on 26 September. So it is plausible that the markets were worried about the undermining of the independent institutions relevant to the UK macroeconomic framework, or else the higher borrowing may have led to an exchange rate appreciation.

To summarise the results, it appears that the Truss episode was associated with a rise in yields because of both higher borrowing and a higher risk premium associated with UK assets. Moreover, the fact that the exchange rate fell is suggestive of the possibility that the ‘risk premium’ channel was more important than the borrowing channel. Assuming an absence of segmentation between the currency and bond markets, it seems plausible to assume that the risk premium channel was similarly more important to the gilts market than the borrowing impact.

One reason, however, for being careful about the above interpretation of movements in exchange rates and gilt yields is that we might have seen ‘contagion’ between the gilts and currency markets. In the context of the 1987 stock market crash, Mervyn King and I argued that rational investors might attempt to infer unobserved information from price changes in other markets (King and Wadhwani 1990). It is therefore possible that another reason that the currency depreciated was because investors assumed that a part of the reason that gilt yields were rising is that other investors had ‘private information’ that was relevant to them.

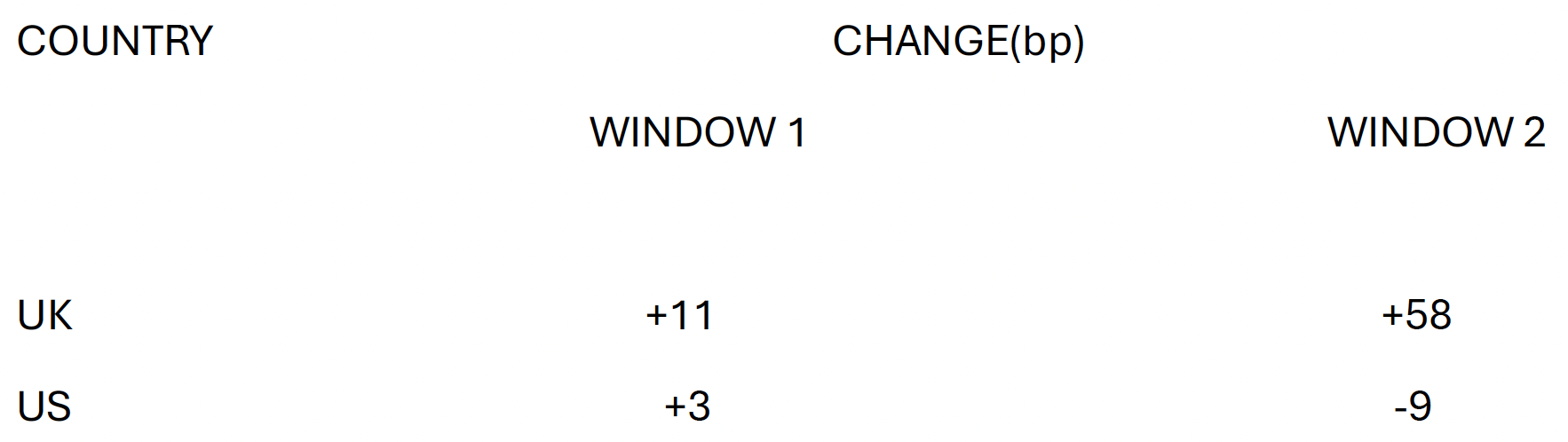

Some caution is also in order because the same worries should have been associated with higher levels of breakeven inflation in the gilts market. Table 3 suggests that whether or not one saw this was dependent on the precise time-window used for the comparison.

Table 3 Changes in 20-year breakeven rates over alternative time-windows for the UK and US

Note: Window 1 relates to 2 August to 27 September; Window 2 is from 2 August to 30 September.

Using the same time window as for the currency, there is, rather surprisingly, not much difference between the rise in the breakeven inflation rate in the US and the UK. But if the time window is extended by a few days until 30 September, the difference between the two countries is highly striking and consistent with what happened to the currency. These results are somewhat puzzling. It is though possible that the index-linked gilt market was distorted because of the deleveraging associated with liability-dependent investment (LDI) flows, and so we should be wary of the published prices until the BOE restored some order after their intervention on 27 September. For example, Pinter (2023) points out that there was significant selling pressure from the LDI sector in some segments of the index-linked market. Indeed, it is these LDI flows that I turn to next.

(iii) LDI flows, deleveraging, and lessons from the 1987 stock market crash

Some investors using LDI strategies became forced sellers during the crisis. This led to the equivalent of what felt like a gilt market crash – by way of example, the price of the March 2046 index-linked gilt fell from 104.9 on 21 September to 68.07 on 27 September! In some ways, this was akin to the October 1987 stock market crash. In that case, the portfolio insurance sector was forced to sell as prices fell. Genotte and Leland (1990) developed an elegant model in which the presence of such forced selling can lead to demand curves becoming perversely shaped. Markets can then become rather illiquid and crashes can occur even with a relatively small amount of forced selling. In the case of the 1987 stock market crash, it was difficult to point to enough news to justify the size of the price fall that occurred on 19 October and this is perhaps why the Brady Commission ended up focusing on the role of portfolio insurance (Brady et al. 1988). Similarly, it is wholly implausible that the news on extra borrowing could explain why the 2046 index-linked gilt fell by over 35% in a matter of few days. Note that Pinter (2023) documents evidence that is suggestive of contagion from the woes of some segments of the index-linked market to the gilt market more broadly.

It therefore seems safe to conclude that at least some of the rise in ten-year gilt yields discussed above was due to deleveraging and not just due to the projected increase in government borrowing.

Bringing it all together: How much of the rise in gilt yields was due to higher government borrowing?

In recent years, a widely cited rule of thumb in the UK has been that a one-year, 1% of GDP unanticipated fiscal loosening generates a peak increase in interest rates of 60 basis points (this is based on a working paper published by the OBR in 2012). More recently, H M Treasury published a policy paper (H M Treasury 2023) where different assumptions are made about some key parameters used in the prior OBR analysis and the likely range of the impact of a fiscal policy loosening of 1% of GDP is therefore widened to between 50 and 125 basis points.

Note that the Kwarteng/Truss budget initially implied a projected fiscal loosening of around 2% of GDP, and so H M Treasury’s numbers would suggest an increase of interest rates ranging between 100 and 250 basis points.

In popular discussion, the Truss episode has become the poster child of the evils of government borrowing. The actual rise in ten-year gilt yields of around 290 basis points appears to be even higher than the upper end of what the Treasury’s range implied.

But this analysis of the episode suggests that the contribution of the higher government borrowing projections was plausibly much smaller than even the OBR’s initial numbers would have implied.

This is best explained in steps:

- The actual rise in yields was 288 basis points

- The implied rise in ‘excess yields’ was around 136 basis points, as perhaps 152 basis points of the rise can be accounted for by the rise in global yields.

- The impact of the attack on macro institutions. I argued above that the impact of undermining the institutions was plausibly greater than that of higher borrowing. I therefore make the working assumption that the two factors contributed equally, which then suggests that the resulting estimate of the impact of higher borrowing falls to 68 basis points.

- The impact of forced deleveraging. It is difficult to estimate the impact of the forced LDI selling, but is likely to have been non-trivial.

- A plausible upper bound of the impact of higher borrowing on gilt yields. Steps 1-4 lead me to conclude that a plausible upper bound estimate of the contribution of higher government borrowing to ten-year gilt yields during the Truss episode is 68 basis points. It is notable that this number is even smaller than the lower end of Treasury estimates, which would have suggested a number of around 100 basis points. Note that reasonable people might disagree with how I dealt with factors (ii) and (iii) above, but I feel that the highly conservative assumption of no effect from deleveraging gives plenty of wiggle room.

Therefore, far from the Truss episode suggesting that we should become more concerned about the impact of borrowing on interest rates than had been true historically, I believe that allowing for other relevant factors suggests that the actual borrowing-related impact on interest rates might have been even smaller than the lower end of the Treasury’s range of estimates!

Some implications for the current conjuncture

There has been much recent discussion in the UK in the run-up to the Budget on whether the Chancellor should modify the existing fiscal rules to allow for more public investment. Some have argued that the resulting increase in the supply of gilts could have highly significant market implications with echoes of the Truss crisis.

I believe that the current Chancellor is in an entirely different place from the backdrop to the September 2022 budget because:

- Far from attacking the OBR or Bank of England, the Chancellor has actually said that she will legislate to strengthen the OBR.

- Although global yields have risen in recent weeks, the rise so far is much smaller than what we saw between August and October 2022. Of course, this will have to be monitored as fears relating to deficits in other countries such as France or the US could easily destabilise global bond markets in the coming period, not least because the US election might have a meaningful impact on the fiscal outlook.

- The OBR/Treasury estimates of higher borrowing on interest rates assume that it represents a pure demand stimulus with no corresponding supply-side benefits. If the Chancellor makes a case that convinces the markets that the higher public investment will yield meaningful supply-side benefits, then the impact on interest rates might be lower. In this regard, Suresh et al. (2024) have, on the behalf of the OBR, produced estimates suggesting that a sustained 1% of GDP increase in public investment could lead to a rise in the level of potential output of around 0.5% after five years and around 2.5% in the long run (50 years). But, as the authors emphasise themselves, these are partial equilibrium estimates that do not take into account the importance of how the investment if financed. Specifically, the US Congressional Budget Office showed that if public investment was financed by borrowing, then the level of GDP would be unchanged at a 30-year horizon because the reduction in funds available for private investment (‘crowding out’) ultimately dampens GDP (CBO 2021). Having said that, both studies agree that GDP rises at a 10-year horizon.

- In the current conjuncture, I would not expect to see much of the LDI-related selling that was observed in 2022. First, I expect LDI investors to be more resilient than in 2022. Second, other opportunistic investors will be more confident of BOE intervention this time around. Having said that, it is always important to be cognizant of vulnerabilities in the markets. In 2022, market chatter about distress in the LDI sector (e.g. Nangle 2022) appears to not have been given enough weight ahead of the Budget.

- If the Chancellor is anxious about the likely market impact of the higher borrowing that might be associated with more public investment, I have previously argued (Wadhwani 2024) that she should go further and allow the Bank of England to set the inflation target – a change that would merely bring the UK in line with the US and the euro area. This would meaningfully reduce the risk of some future government deciding to move the inflation target higher and markets would take some comfort from that. This government should expect to be rewarded for this action by lower breakeven inflation and interest rates.

Conclusions

Although the Kwarteng/Truss Budget of 2022 is held up as a poster child for why higher government borrowing leads to a significant impact on bond yields, I have argued that once one allows for other relevant factors, the underlying impact of the higher budget deficit on gilt yields was plausibly less than one-quarter of the actual observed increase in interest rates. Moreover, my estimate of the borrowing-related impact on interest rates during the Truss episode is even smaller than the lower end of the range of likely impacts published by H M Treasury.

Author’s note: The author is a former member of the UK Chancellor’s Economic Advisory Council and the Monetary Policy Committee at the Bank of England. He writes in a personal capacity, and is extremely grateful to Enrique Sentana for helpful comments.

References

Bank of England (2022), “Bank of England announces gilt market operation”, 28 September 2022.

Brady, N F, Cotting, J C, R G Kirby, J R Opel and H M Stein (1988), Report of the Presidential Task Force on Market Mechanisms, U.S. Government Printing Office.

Congressional Budget Office (2021) “Effects of Physical Infrastructure Spending on the Economy and the Budget Under Two Illustrative Scenarios”, August.

Financial Times (2024) “Cost of borrowing mounts as Reeves walks 'tightrope' over spending plans”, 8 October 8.

Genotte, G, and H Leland (1990) “Market Liquidity, Hedging, and Crashes”, The American Economic Review 80(5): 999-1021.

H M Treasury (2023), “Annex: The Impact of borrowing on interest rates”, Policy Paper.

King, M and S Wadhwani (1990), “Transmission of Volatility between Stock Markets”, The Review of Financial Studies 3(1),: 5-33.

King, M, E Sentana and S Wadhwani (1994), “Volatility and Links between National Stock Markets” , Econometrica 62(4): 901-933.

Nangle, T (2022), “The big collateral call facing UK pension funds”, Financial Times, 21 July.

OBR - Office for Budget Responsibility (2012), “A small model of the UK economy”.

Pinter, G (2023), “An anatomy of the 2022 gilt market crisis”, Bank of England Staff Working Paper No. 1019.

Suresh, N, R Ghaw, R Obeng-Osei, and T Wickstead (2024) “Public Investment and potential output”, OBR Discussion Paper No. 5, August.

Wadhwani, S (2024), “How to cut the UK debt interest bill”, VoxEU.org, 22 July.