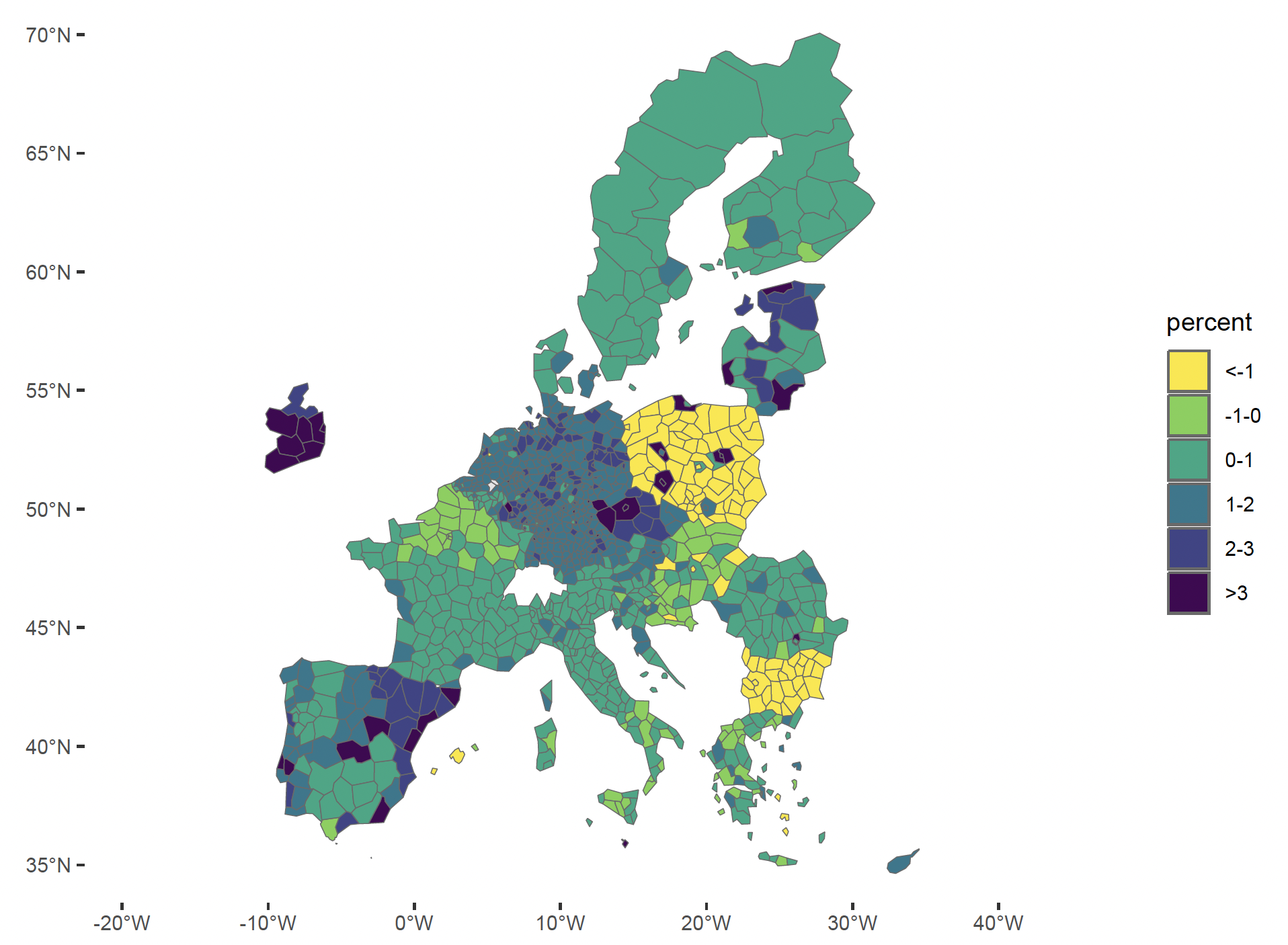

Immigration into the EU accelerated sharply after the onset of the war in Ukraine, reaching a historic high of around 6.5 million in 2022, taking into account the roughly 4 million refugees from Ukraine. Inflows eased in 2023 but remained significantly above pre-pandemic averages. Both the size and the composition of the population increase differ across the EU (Figure 1). In Central and Eastern Europe and Germany, refugees from Ukrainian played an outsized role in raising immigration, while Latin Americans made the largest contribution in Spain.

Figure 1 Crude rate of net migration by NUTS 3 regions, 2022

Source: Eurostat

Notes: The crude rate of net migration plus adjustment is defined as net migration during the year in percent of the average population in that year. The data for Bulgaria, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden do not include Ukrainian refugees under the temporary protection scheme. The data for Bulgaria, Denmark, Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Slovenia, Slovakia, Finland and Sweden do not include asylum seekers.

Amid a challenging demographic outlook – the EU’s working age population is expected to contract sharply into the 2030s (Eurostat 2023) – the high level of non-EU immigration allowed the EU’s population to grow in 2022 and 2023 at the fastest rate in many years. The old-age dependency ratio – though still rising – rose more slowly than in previous years.

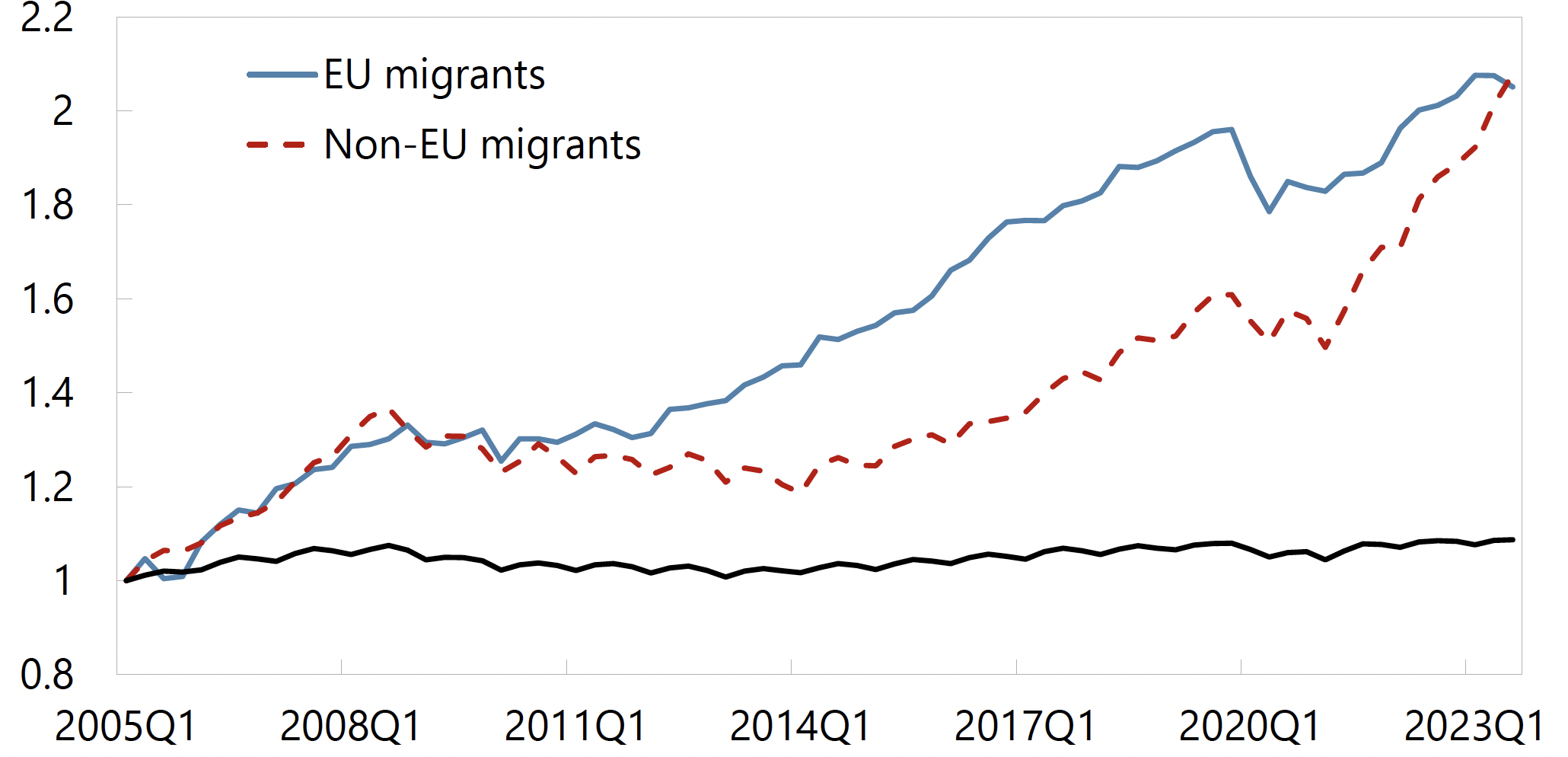

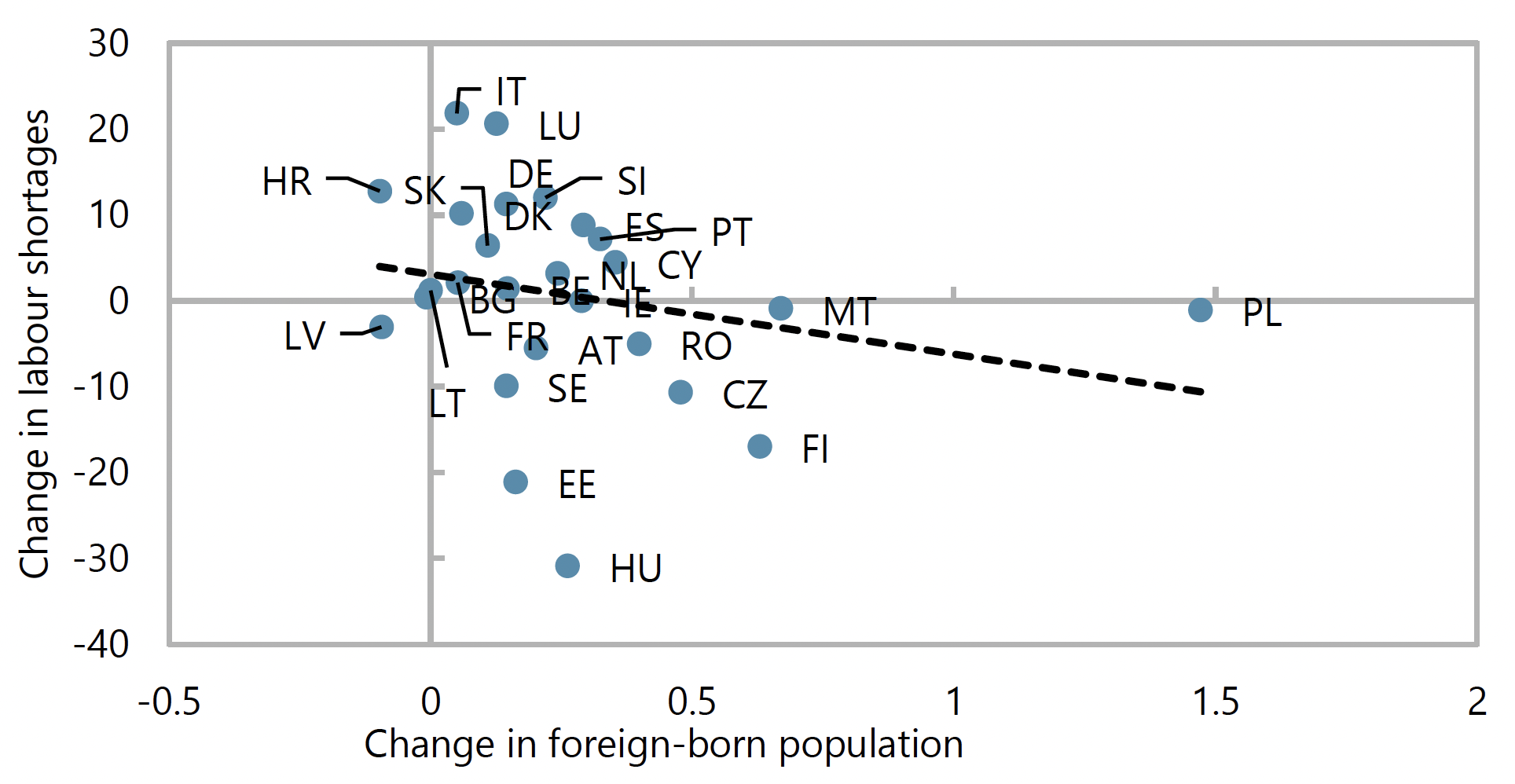

Immigration also helped meet unprecedentedly strong labour demand in Europe during 2022-23, with close to two-thirds (2.7 million) of the EU jobs (4.2 million) created between 2019 and 2023 filled by non-EU citizens. This led to an acceleration of a longer-run trend, whereby both EU and non-EU migrants roughly doubled their share in total employment (Figure 2). At the same time, the unemployment rate of EU citizens remained at historic lows, suggesting immigrants helped alleviate labour shortages to some degree (Figure 3).

Figure 2 EU employment index by citizenship (2005Q1=100)

Sources: Eurostat and IMF staff calculations.

Figure 3 Correlation between labour shortages and change in foreign-born population (EU27; 2019Q1-2023Q4; percentage points)

Sources: European Business and Consumer surveys; Eurostat; IMF staff calculations

Note: Change are over the period 2019Q1-2023Q4. Labour shortages are averaged across industry, construction and services.

During this period, Ukrainian refugees seem to have been absorbed into employment faster than previous refugee waves, despite historically low employment rates of immigrant women (Solmone and Frattini 2022). This reflects not only tight labour market conditions in Europe (Verwey et al. 2023) but also the fact that the temporary protection scheme allowed Ukrainian refugees to look for work almost immediately (Pogarska et al. 2023, Eurofound 2024, Honorati et al. 2024).

Impact of immigration on potential output

What does this increase in labour force mean for Europe’s production capacity (or potential GDP)? A mapping of the effect of higher (immigrant) labour supply to potential GDP is not trivial. A large literature shows that immigration can have positive effects on total factor productivity (TFP) – for example through innovation and knowledge diffusion (e.g. Lewis and Peri 2015, Bahar and Rapoport 2018), in addition to positive effects through greater labour supply (Engler et al. 2023, IMF 2020). However, this requires a proper matching of immigrants’ skills to jobs, which takes time. Overqualification among immigrants in Europe is common (Dalmante and Frattini 2024). In the near term, a significant increase in labour supply without accompanying increases in capital stock (as investment takes time to ramp up) could temporarily lower labour productivity. As a case in point, while employment in 2023 stood above pre-pandemic projections, labour productivity fell short of pre-pandemic projections (by the IMF and others).

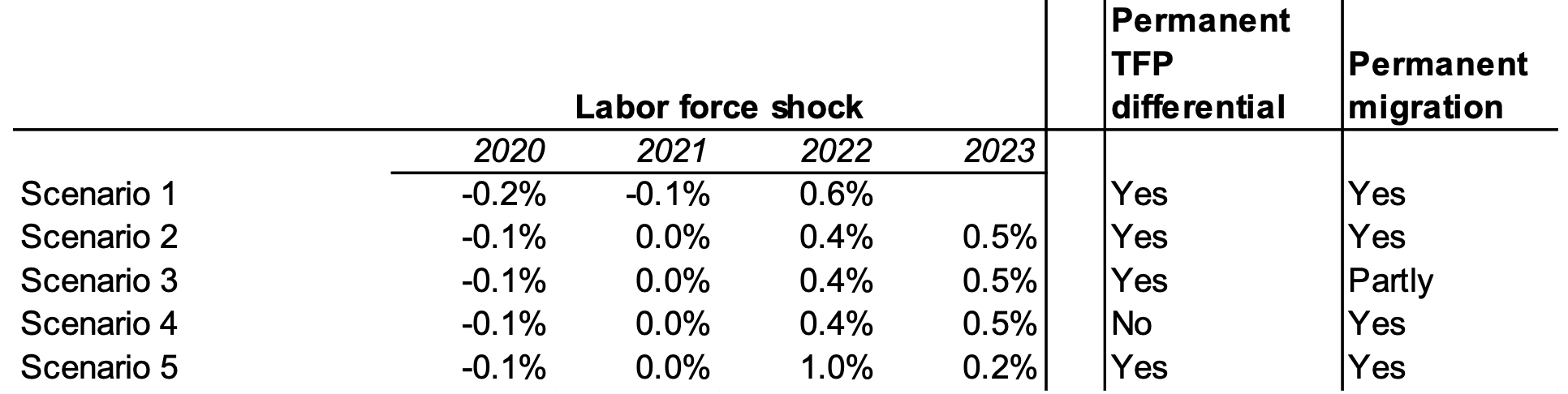

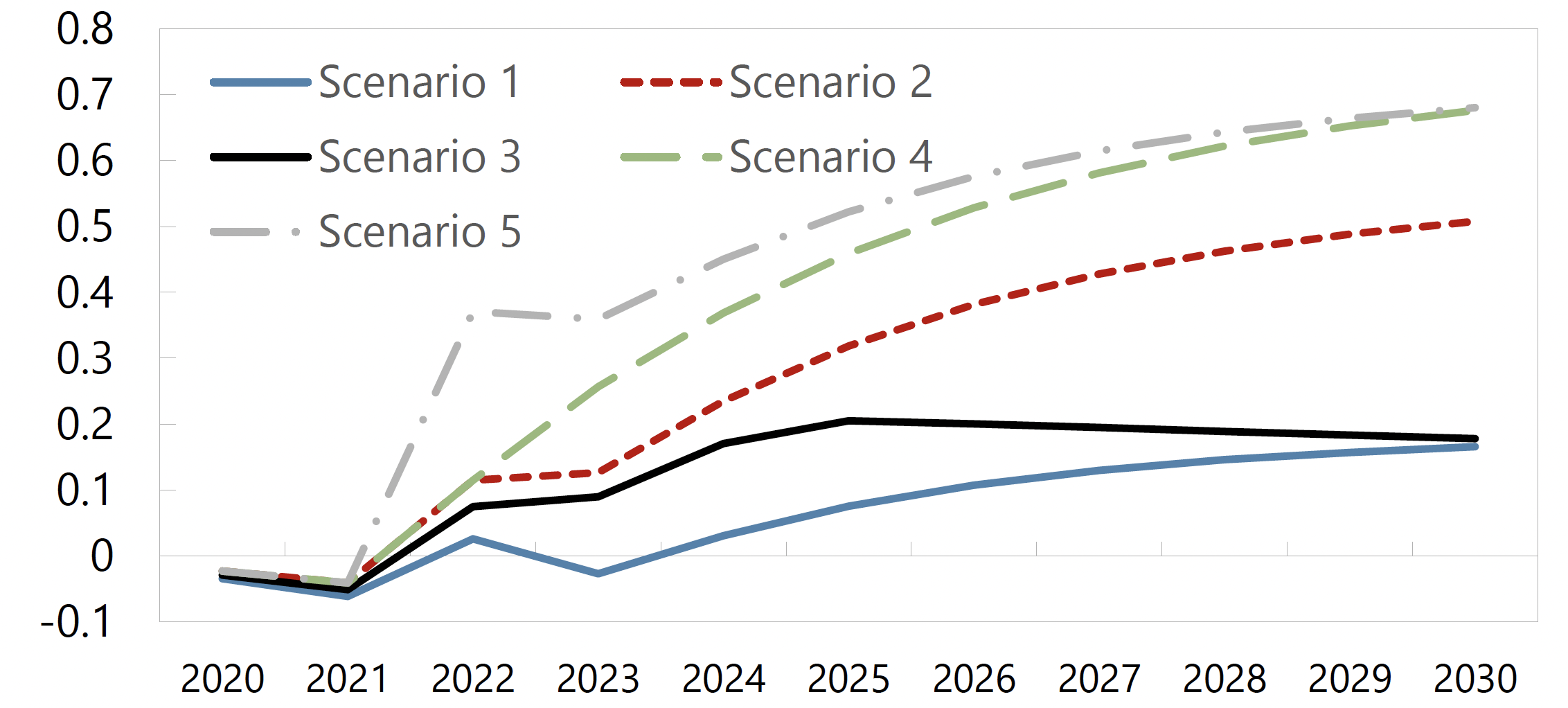

Using a semi-structural general equilibrium model (Andrle et al. 2015), in a recent paper we simulate the impact of the recent increase in immigration – relative to pre-pandemic expectations – on potential output in the euro area (see Caselli et al. 2024). As summarised in Table 1, we consider five scenarios which combine different assumptions on the size of the working age population shock, the productivity differential between migrants and natives (either a permanent gap or a gap that slowly closes over time) and the length of migrants stay in the domestic economy, given many have intentions to return home, as in the case of refugees from Ukraine (Adema et al. 2024).

Table 1 Euro area: Key assumptions in different model scenarios

Sources: Author’s calculations.

We find an impact on the level of potential output in 2030 of 0.2-0.7% (Figure 4), with a central estimate of 0.5% (slightly less than half the euro area’s annual potential GDP growth at that time). Potential output also grows at a faster pace in the short term due to capital stock catching up with the larger labour supply. However, the impact on GDP per capita depends crucially on how productivity develops. If a permanent wedge between migrants and natives remains – for example, due to a lack of relevant skills or unsuccessful labour market integration – the impact would be negative. However, as capital stock catches up in the longer term, the negative effect on GDP per capita would fade away. The simulation results use a similar methodology and deliver consistent results with recent IMF work on the impact of Venezuelan refugee flows to Latin America (Alvarez et al. 2022), and the inflow of refugees to the EU in 2015-16 (Aiyar et al. 2016).

Figure 4 Potential output impact of labour force increases

Sources: Authors' calculation based on IMF Flexible System of Global Models.

Fiscal and local implications

Previous IMF work has shown that the increased migration caused initial fiscal costs of around 0.2% of EU GDP and as high as 1% of GDP in those countries with the largest per capita inflow of refugees (IMF 2022). As shown in the literature, the medium- and longer-term fiscal impact will be determined to a large extent by the labour market outcomes of migrants – in other words, the extent to which they enter into and remain in productive employment. Beyond the fiscal costs, the impact on native labour market outcomes, as well as ‘congestion’ costs related to the crowding of the per capita provision of public services, are often discussed with concern.

Data constraints mean it is too early for a meaningful analysis of the wage impact of the recent increase in immigration. The broader literature tends to find possible adverse effects of immigration on some native wages in the short run, due in large part to differences between migrants’ and native workers’ skills (see Edo 2019 for a recent review among many others). However, in the longer run the impact on native wages is generally found to be positive.

In terms of congestion costs (for example, a reduction in the per capita provision of public goods), amid large local population shocks in some regions in 2022 (as high as 3% of the population) and an inelastic supply of public services and amenities (including housing), anecdotal evidence suggests resources were stretched in some places (OECD 2022, Eurofound 2023, FRA 2023, Szymanska 2023).

Policy priorities

Two policy priorities emerge from the research, fully aligned with the literature. To improve output trends amid rapidly ageing populations and tight labour markets, governments need to focus on integrating migrants into the labour market, in the most productive way possible, and to make sure the supply of public services and amenities (including at the local level) keeps up with the population increase.

- Further efforts to facilitate labour market access for immigrants not under the Temporary Protection Directive should be pursued, including minimising restrictions on taking up work during the asylum application phase. Easing avenues for migrants to enter self-employment (including access to credit), facilitating skill recognition, strengthening language training, and improving rental housing affordability and supply could also help. Finally, strengthening the role of the non-governmental sector – drawing for example on the experience of Germany, which has built a strong network of collaboration between government, NGOs, CSOs, and the private sector – can support integration (Honorati et al. 2024). In addition, reducing barriers to geographical mobility (including those linked to housing, education, and health services) would allow migrants to move where labour demand is high.

- National governments, and possibly the EU, should carefully study whether the needed mechanisms are in place to avoid a sudden decline in the provision of local public goods (such as schooling and social housing) at the per capita level, as a result of an influx of immigrants. Currently, public data do not allow an in-depth assessment of this question, so establishing whether per capita public good provision has been negatively affected is an important first step. Regions relying more on local financing may require greater initial support from regional, central, or supranational governments to ensure continuity of services.

Authors’ note: The views expressed in this column are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

References

Adema, J, C G Aksoy, Y Giesing and P Poutvaara (2024), “Understanding return intentions and integration of Ukrainian refugees”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Aiyar, S, B Barkbu, N Batini, H Berger, E Detragiache, A Dizioli, C Ebeke, H Lin, L Kaltani, S Sosa, A Spilimbergo and P Topalova (2016), “The Refugee Surge in Europe: Economic Challenges,” IMF Staff Discussion Note, SDN/16/02.

Alvarez, J, M Arena, A Brousseau, H Faruqee, E W Fernandez Corugedo, J Guajardo, G Peraza and J Yepez (2022), “Regional Spillovers from the Venezuelan Crisis: Migration Flows and Their Impact on Latin America and the Caribbean,” IMF Departmental Paper.

Andrle, M, P Blagrave, P Espaillat, K Honjo, B Hunt, M Kortelainen, R Lalonde, D Laxton, E Mavroeidi, D Muir, S Mursula and S Snudden (2015), “The Flexible System of Global Models – FSGM,” IMF Working Paper, WP/15/64.

Bahar, D and H Rapoport (2018), "Migration, Knowledge Diffusion and the Comparative Advantage of Nations,” The Economic Journal 128(612): F273-F305.

Caselli, F, H Lin, F Toscani and J Yao (2024), “Migration into the EU: Stocktaking of Recent Developments and Macroeconomic Implications,” IMF Working Paper, WP/24/211.

Dalmonte, A and T Frattini (2024), “Skilled but struggling: The ‘brain waste’ dilemma of migrants in Europe”, VoxEU.org, 13 August.

Edo, A (2019), “The Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market,” Journal of Economic Surveys 33(3).

Engler, P, M MacDonald, R Piazza and G Sher (2023), “The Macroeconomic Effects of Large Migration Waves”, IMF Working Paper, WP/23/259.

Eurostat (2023), Population Projections in the EU.

Honorati, M, M Testaverde and E Totino (2024), “Labor market integration of refugees in Germany: new lessons after the Ukrainian crisis”, World Bank Social Protection & Jobs Discussion Paper, No. 2404.

International Monetary Fund (2020), “The Macroeconomic Effects of Global Migration”, World Economic Outlook, Chapter 4, April 2020.

Lewis, E and G Peri (2015), "Immigration and the Economy of Cities and Regions", in Handbook of Regional and Urban Economics 5: 625-685.

Pogarska, O, O Tucha, I Spivak and O Bondarenko (2023), “How Ukrainian migrants affect the economies of European countries”, VoxEU.org, 7 March.

Solmone, I and T Frattini (2022), “The labour market disadvantages for immigrant women”, VoxEU.org, 30 March.

Verwey M, A Kiss, C Tinti, and K Van Herck (2023), “A modest recovery ahead after a challenging year”, VoxEU.org, 22 November.