The rise in the use of non-tariff measures, especially in the form of antidumping duties and countervailing duties, has been widely recognised and dramatically changed the landscape of trade policy. Bown (2012) points out that temporary trade barriers are of vital importance because of their wide usage. Using a sample of major G20 users of temporary trade barriers over the period 1990–2009, Bown shows that low- and middle-income countries increase their use of temporary trade barriers, especially to combat the global financial crisis, while high-income countries are primarily the opposite.

However, the recent trade spats over battery electric vehicles (BEVs) between the EU and China, as well as Canada and China, might suggest that high-income countries may also increase their use of non-tariff measures due to precautionary motives, to avoid losing strategic opportunities for future developments.

On 4 July 2024, the EU announced the imposition of countervailing duties on imports of Chinese BEVs on top of the existing 10% tariff. According to UNCTAD (2015), countervailing duties are a type of contingent trade-protective non-tariff measures. They are designed and implemented to counteract adverse effects from imports in the importing country’s market, contingent upon the fulfilment of procedural and substantive requirements. The extra duties targeted Chinese vehicle manufacturers that the EU claimed to have received ‘unfair subsidisation’ from the Chinese government. The subsidization purportedly was threatening economic injury to European producers by lowering the world price. These duties included 17.4% for BYD vehicles, 19.9% for Geely, and 37.6% for SAIC (European Commission 2024b).

The Chinese government and vehicle producers have publicly denied these accusations (Ministry of Commerce 2024). On 9 August 2024, China lodged a complaint through the WTO dispute settlement mechanism, further complicating the dispute (BNN Bloomberg 2024). On 20 August, the European Commission disclosed the draft decision to impose countervailing duties on the imports of BEVs from China with slight adjustments to the previously proposed duties. These duties included 17.0% for BYD, 19.3% for Geely, and 36.3% for SAIC, with Tesla as an exception regulated by a low rate at 9% (European Commisssion 2024a).

Meanwhile, on 26 August 2024, the government of Canada announced its intention to implement a 100% surtax on all Chinese BEVs, effective 1 October 2024. This surtax will apply in addition to the 6.1% tariff that currently applies to electric-vehicle imports from China. According to UNCTAD (2015), a surtax is a customs surcharge type non-tariff measures (F4), levied solely on imported products in addition to tariffs to raise fiscal revenues or protect domestic industries.

All these ongoing trade disputes over Chinese BEVs involve the importing countries – such as the EU and Canada – mixing seemingly opposite trade policies, tariffs, and non-tariff measures, for the same policy goal of stopping or slowing down the imports of Chinese BEVs. Why do countries mix trade policies? Does trade-policy mixing depend on the characteristics of the products, importing countries, or export countries?

Trade policy mix and match: Trade model with consumption externality

In our paper Kee and Xie (2024), we analyse the Sino-EU electric vehicle disputes in the context of the trade policy choices of the EU, without taking a stance on this issue. We focus on shedding light on the policy actions of the EU in response to the lower world price of BEVs. The underlying reasons for these trade policy actions are likely far more complex than any economic model can capture. They may involve balancing competing objectives, such as developing domestic BEV production capacity in the longer run and addressing current climate issues or pollution. Additionally, domestic political factors, as well as international geopolitical factors, are considered. We abstract from all these factors and focus on how the EU government may use non-tariff measures to promote social welfare on a product that may have consumption externality, given that tariffs are already in place. Such a simplification is necessary to distil any policy lessons we can learn from analysing this ongoing real-world dispute.

BEV is a product with consumption externalities. On the one hand, BEV imports may lead to more congestion if BEVs more than replace the gasoline vehicles on the road, hence generating negative consumption externalities. On the other, BEVs are green products that are less polluting than gas vehicles, and the public is happier to see more BEVs, hence exerting positive consumption externalities. In both cases, it is essential to analyse the trade dispute using a model with consumption externalities, and we thus analyse this trade dispute through the lens of our terms-of-trade model with consumption externalities.

In equilibrium, EU imports of BEVs equal exports from China, which determines the equilibrium world price. Any factors that increase net BEV exports from China lead to a lower world price and an increase in EU imports of BEVs. One such factor could be Chinese government subsidies, as argued by the EU. Other possible factors include technological advancement or productivity gains in China, which could also increase BEV exports, resulting in a lower world price. For the purpose of this analysis, the reasons behind the increase in Chinese BEV exports are not as important and will not affect our results.

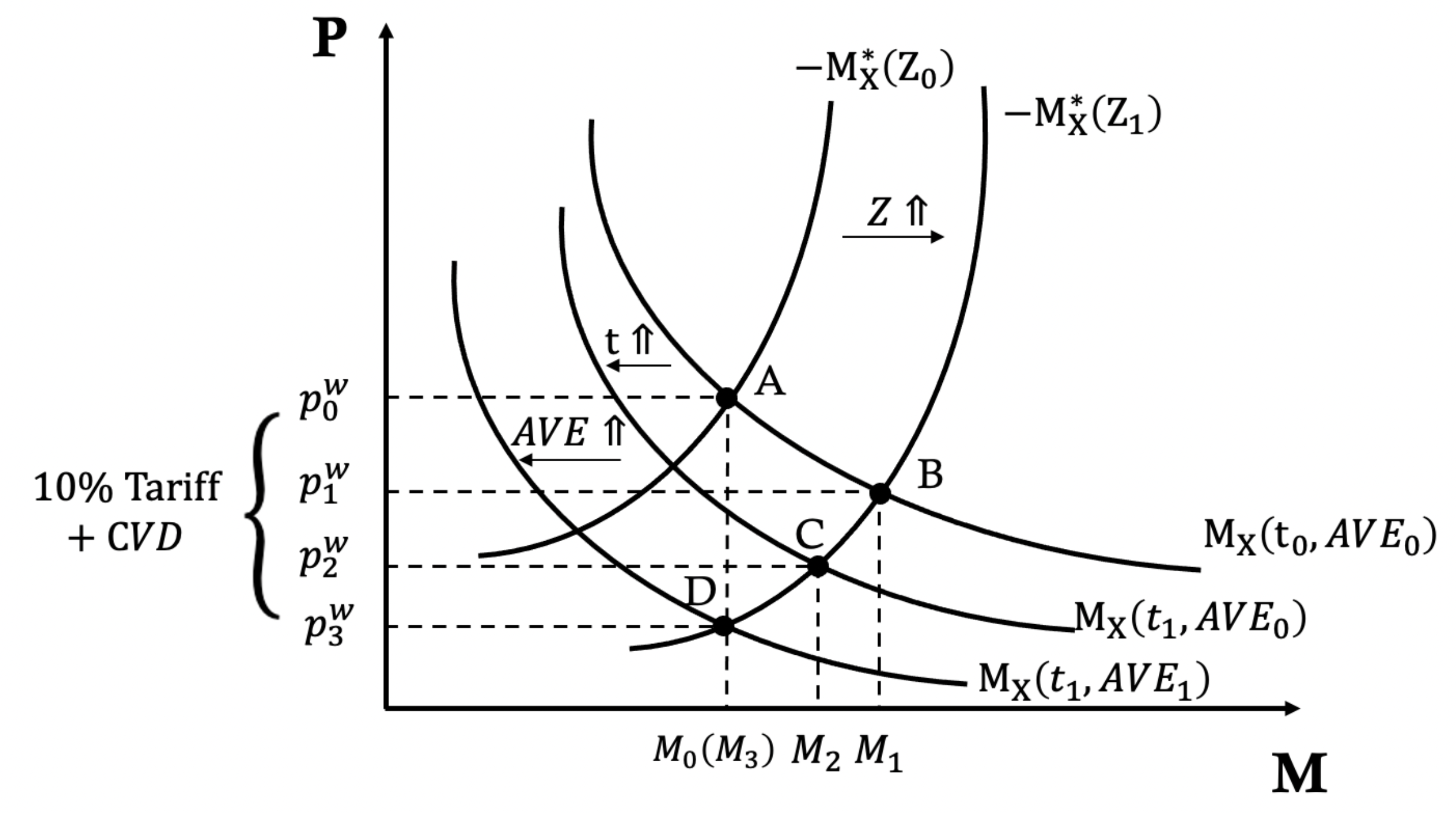

Figure 1 nicely illustrates the Sino-EU BEV disputes. Given the initial downward-sloping import demand curve and the initial upward-sloping export supply curve of BEVs, the initial market equilibrium is at point A. A change in the supply-side factor, Z, which could be the state subsidies of the Chinese government, technological advancement, or productivity gains in China, shifts the upward-sloping export supply curve to the right, leading to a lower world price and an increased quantity imported, at point B. Confronting the lower world price and the larger imports, the EU’s existing 10% tariff on imports of BEVs from China shifts the downward-sloping import demand curve leftward and reduces the import, at point C. On top of this tariff, imposing NTMs will further shift the import demand curve leftward, leading to an additional decrease in the import of BEVs, at point D, to fully offset the increase in imports due to the change in factor Z. The use of NTMs, in addition to tariffs to further reduce imports, nicely demonstrates that tariffs and NTMs are substitutive trade policy instruments. Overall, the mixed-use of tariffs and NTMs could capture the terms-of-trade gains and cancel out the impacts on BEV imports due to any supply-side factors, such as the Chinese state subsidies or productivity gains.

Figure 1 Sino-EU battery electric vehicle dispute

Source: Kee and Xie (2024).

So, why do countries mix trade policies? Our analysis suggests that one reason is that they want to maximise their social welfare involving products with consumption externalities. Both tariffs and non-tariff measures have terms-of-trade gains, but non-tariff measures may also improve social welfare directly if there are consumption externalities, and the use of non-tariff measures may boost public confidence in the government in controlling such externalities.

And does mixing of trade policy depend on the characteristics of the products, importing countries, or export countries? As emphasised by both Bown (2012) as well as Beverelli and Bacchetta (2012), product-level analysis is needed to examine the complementarity and substitutability of tariffs and non-tariff measures. Using highly disaggregated importer-exporter-HS 6-digit product-level data, our analysis concludes that it does. Empirical results confirm that overall tariffs and non-tariff measures are policy substitutes in the sense that governments impose more restrictive non-tariff measures on products or trading partners with lower tariffs.

However, depending on the characteristics of the importing countries, exporting countries, and products, governments also mix and match tariffs and non-tariff measures, which may turn the relationship between them to be less substitutive and may even be complementary. Specifically, high-income, capital-abundant, or skilled-labour-abundant importing countries tend to impose more liberal tariffs and restrictive non-tariff measures. This is the case for the EU. On the other hand, exporting countries that are labour-abundant or have lower income often face more liberal tariffs and restrictive non-tariff measures. China is in this category. Policy substitution is further found in consumption products, agricultural products, food and beverage products, and, in general, products with externalities. BEVs are products with consumption externalities. Put together, the case of the Sino-EU BEV dispute makes the perfect storm for trade policy mixing. This is what we observe in real life right now.

Our empirical results also show that countries that participate in global value chains or products relying on global value chains, such as capital goods and intermediate goods, tend to witness complementary reductions in both non-tariff measures and tariffs. However, as Nicita and de Melo (2019) note, the WTO leaves substantial policy space for governments to use non-tariff measures to advance their domestic objectives, making policy substitution between tariffs and non-tariff measures possible.

While many have hoped to use trade agreements to curb such policy substitution, alleviate the negative impact of non-tariff barriers on trade, and harmonise regulatory heterogeneity (Beverelli and Bacchetta 2012, Grossman et al. 2019, Sandkamp et al. 2019), our analysis suggests that these hopes may be in vain: the degree of substitution between tariffs and non-tariff measures tends to be larger for country pairs engaged in deep trade agreements (Fernandes et al. 2021 offer a concise and insightful introduction to deep trade agreements).

Finally, in the current climate of geopolitical fragmentation with the rise of reshoring, nearshoring, and deglobalisation, our analysis suggests that we are entering an era of more mixed use of policies, resulting in more substitution between tariffs and non-tariff measures.

Conclusion

Governments may expand the mixed use of tariffs and non-tariff measures to achieve domestic economic or political agendas. More attention is needed on the trade-off between short-term gains stemming from a beggar-thy-neighbour policy and long-term sustainable gains originating from a win-win strategy.

Authors’ note: The results and opinions presented in this column do not represent the views of our institutions or the countries we represent.

References

Beverelli, C, and M Bacchetta (2012), “Non-tariff measures and the WTO”, VoxEU.org, 31 July.

BNN Bloomberg (2024), “China challenges EV tariffs imposed by Europe with WTO complaint”, BNN Bloomberg, 9 August.

Bown, C P (2012), “Import protection update: Antidumping, safeguards, and temporary trade barriers through 2011”, VoxEU.org, 18 August.

European Commission (2024a), “Commission discloses to interested parties draft definitive findings of anti-subsidy investigation into imports of battery electric vehicles from China”, press release, 20 August.

European Commission (2024b), “Commission imposes provisional countervailing duties on imports of battery electric vehicles from China while discussions with China continue”, press release, 4 July.

Fernandes, A M, N Rocha, and M Ruta (eds) (2021), The economics of deep trade agreements, CEPR Press.

Grossman, G M, P McCalman, and R Staiger (2019), “The ‘new’ economics of trade agreements”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 13903.

Kee, H L, and E Xie (2024), “Trade policies mix and match: Theory, evidence and the Sino-EU electric vehicle disputes”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper WPS10855.

Ministry of Commerce, People’s Republic of China (2024), “MOFCOM regular press conference (July 4, 2024)”, 5 July.

Nicita, A, and Jaime de Melo (2019), “The implications of non-tariff measures for developing countries’ exports”, VoxEU.org, 4 May.

Sandkamp, A, E Yalcin, and L Kinzius (2019), “Global trade protection and the role of non‑tariff barriers”, VoxEU.org, 16 September.

UNCTAD (2015), International classification of non-tariff measures, United Nations Publications.