The banking turmoil in March 2023 was a stark reminder of the fragility associated with banks’ funding structures, especially when they rely on an inadequately diverse uninsured deposit base (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2023, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2023, Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority 2023, Admati et al. 2023, Honohan 2023). These cases provided new evidence of the speed at which, in a world of digital banking and social networks enabling the rapid flow of information, adverse news on a bank’s solvency or liquidity position can put it on the brink of failure in a matter of weeks, if not days or even hours. A few days after the Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank failures, the forced merger of Credit Suisse with UBS showed how the legacy and viability problems of a larger bank, if left unresolved for a long period, may also crystallise in the need for a sudden intervention by the authorities when investor confidence breaks down, deposits are withdrawn on a massive scale, and access to market funding is lost.

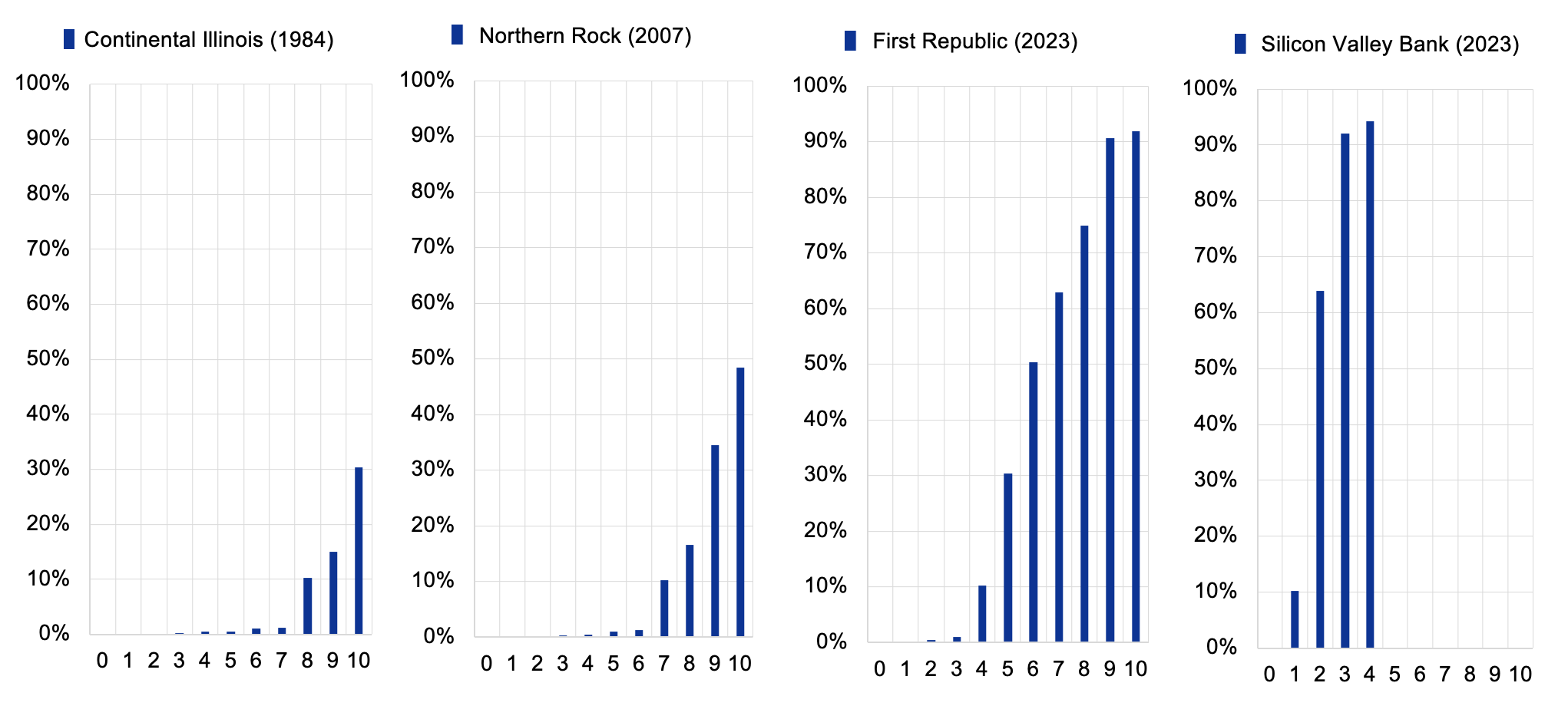

To illustrate the vulnerability of banks to runs, Figure 1 simulates the implications for the EU banking system of deposit withdrawals with the speed and intensity of those seen in specific run episodes. For each selected case, each panel shows as a function of the number of days into a run episode, which share of total assets of the EU banking system would stay at banks able to withstand the deposit withdrawals with their available liquidity (cash, central bank deposits, and demand deposits) and without access to any refinancing. Despite its stark assumptions, this hypothetical simulation shows that, in the absence of external liquidity support, a large part of the EU banking system would be able to cope with deposit outflows like those witnessed during the global crisis (e.g. Northern Rock in 2007), but only a very small proportion would be able to withstand runs like those at Silicon Valley Bank or First Republic.

Figure 1 Application of some of the largest historical deposit outflows to the EU banking sector (percentages)

Source: ESRB Secretariat calculations based on the EBA’s 2022 Transparency Exercise.

Notes: The x-axis shows number of days into the run and the y-axis shows the share of total assets in the total assets of the EU banking system of those banks that would not have enough liquid assets (cash, central banks, and demand deposits) and debt securities to compensate for outflows of household and non-financial corporation deposits under different deposit outflow scenarios. To arrive at the percentages along the y-axis, we follow two steps. First, each individual bank participating in the EBA’s 2022 Transparency Exercise is assumed to experience the same path of deposit outflows (in proportional terms) as the banks that suffered each of the runs shown, and we assess whether each of the banks would have enough liquid assets to cope with these outflows. Second, the total assets of those banks unable to cover deposit outflows with existing liquid assets are computed as a share of total assets of the EU banking system. The path of deposit withdrawals associated with each run is extracted from the data reported in Rose (2023) and HM Treasury (2009). Balance sheet data for the sample of EU banks are taken from the EBA’s 2022 Transparency Exercise, which has a reference date of June 2022.

In a recent report of the Advisory Scientific Committee (ASC) of the European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), we discuss, from an academic perspective, a range of possible policies to adjust banks’ regulatory and supervisory frameworks in light of the lessons learned from these episodes (Beck et al. 2024a). The views expressed in the report, as with all reports by the ESRB ASC, do not represent the official stance of the ESRB.

Deposit funding and the risk of runs

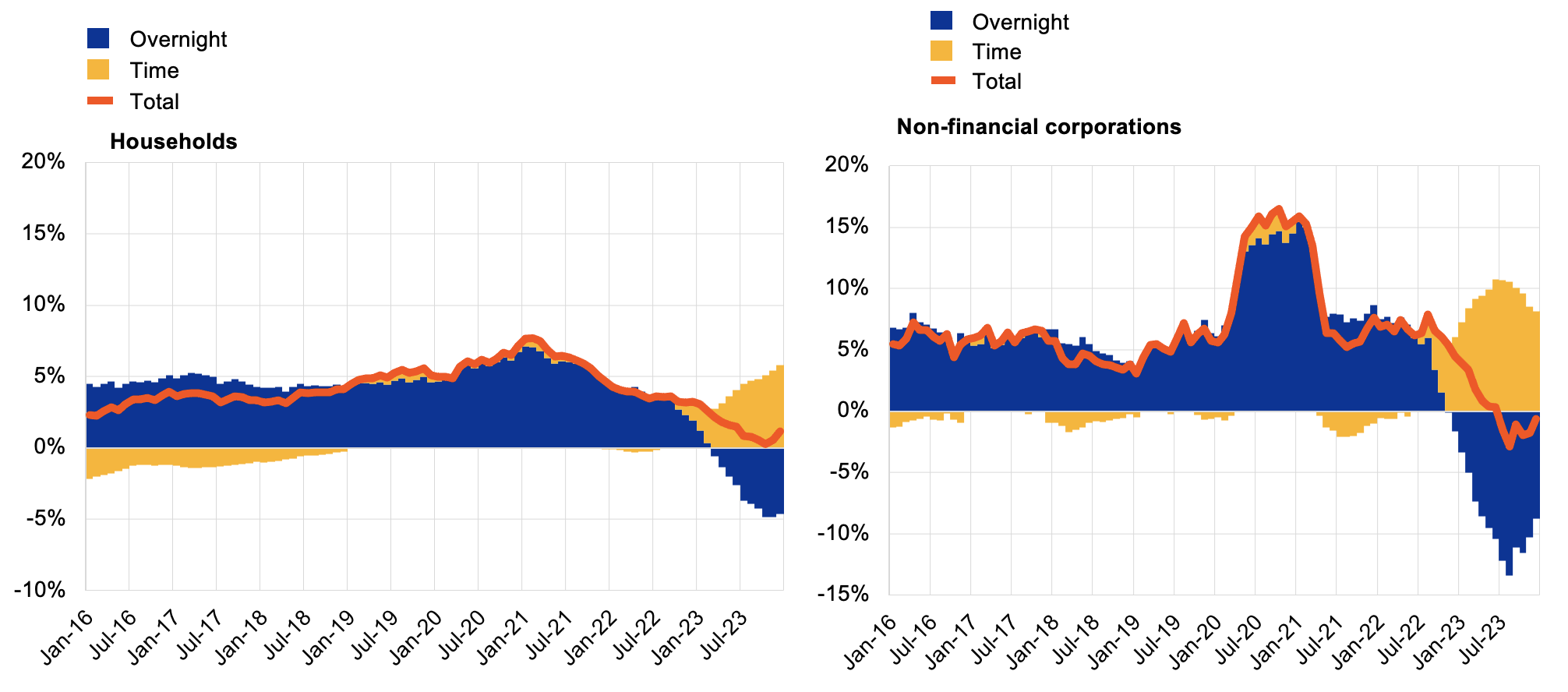

Deposits are the primary source of funding for European banks, although their importance varies substantially across EU member states, with insured deposits accounting on average for 37% of total deposits and 92% of depositors being completely covered. At the onset of the recent high inflation period, banks in both the EU and the US had record levels of overnight deposits from households and non-financial corporations. However, the trend reversed as interest rates began increasing in 2022, especially for non-financial corporations. Figure 2 shows a flow from overnight to time deposits of both households and non-financial corporations. In this tightening phase of monetary policy, the pass-through of policy rates to deposit rates was incomplete, varied across different types of deposits, and was slower than in previous tightening phases.

Figure 2 Deposits of households and non-financial corporations in the euro area: Year-on-year growth rates (percentages)

Source: ESRB Secretariat calculations based on ECB (BSI Statistics).

Notes: The latest observation is for December 2023. Time (or term) deposits include deposits with agreed maturity and deposits redeemable at notice. The red line shows the yearly growth rate of deposits, and the blue and yellow bars represent the contribution of overnight and time deposits respectively.

Deposit runs are a major source of bank fragility. They almost always result from a combination of weak fundamentals (concerns about the solvency or liquidity position of a bank or the banking system) and the strategic considerations of depositors who may withdraw funds in response to information they receive (Rochet and Vives 2004, Matta and Perotti 2024). The runs observed in the US in March 2023 unfolded much more rapidly than previous ones, fuelled by the concentration of the depositor base of the affected banks, their large share of uninsured deposits, the role of social media, and the feasibility of making fast (instant) payments and transfers from the accounts of the banks affected. All of this forced supervisors to intervene much more rapidly than in previous crises.

According to evidence from the academic literature, uninsured depositors are much more prone to withdraw deposits during a bank run than insured depositors (Iyer and Puri 2012, Martin et al. 2024). When bank solvency problems are widespread, depositors seek refuge in banks that, because of their size or systemic importance, are more likely to ensure their depositors are fully protected or at least more favourably treated in the resolution process (Iyer et al. 2019, Acharya et al. 2023). Formal deposit insurance is effective in making deposits attractive to depositors and providing a stable base of ‘information-insensitive’ funding for banks. However, it may come at the cost of moral hazard if individual banks are willing (and able) to compete for deposits more aggressively, especially when they are weak, and therefore take excessive risks (Ioannidou and Penas 2010, Anginer et al. 2014).

Interest rate risk is at the core of banking business

Losses due to the rise in interest rates were a trigger of the runs observed in the US. Exposure to interest rate risk is a direct consequence of banks’ involvement in maturity transformation. There is evidence that many banks enjoy a natural interest rate hedge due to their ‘deposit franchise’

(Drechsler et al. 2021). But individual banks or business models may fail to be effectively hedged against interest rate risk. The bank failures in the US in early 2023 show that the franchise and hedging value of deposit funding is vulnerable to any force that leads depositors to withdraw their funds or suddenly requires banks to pay much higher rates to roll over their deposits.

There are multiple ways in which interest rate risk interacts with banks’ funding structure, which should be considered by regulators, in conjunction with the safety guarantees and the capital and liquidity position of each bank, rather than with a single-dimensional tool (Suarez 2023). The larger and more stable a bank’s deposit franchise, the lower the minimum capital necessary for it to remain solvent when interest rates spike unexpectedly. Thus, if the system can guarantee the stability of a greater fraction of deposits during crises, the minimum capital needed to ensure a bank stays solvent declines. Prudential authorities therefore face a trade-off between requiring more capital of banks and extending the coverage of the safety net for their deposits. Alternatively, imposing a minimum fraction of highly liquid assets provides an immediate buffer to cope with outflows without the need to sell longer-term or less liquid assets. But holding more liquidity reduces banks’ expected net interest income and may result in them being less able to accumulate loss-absorbing capacity.

Policy challenges

While the bank failures in March 2023 revealed the idiosyncratic weaknesses of each of the banks affected, they also highlighted the importance of taking a holistic approach to addressing vulnerabilities associated with deposit funding and interest rate risk.

In the case of the large regional US banks that failed, imprudent exposure to interest rate risk in the context of a peculiar business model was compounded by (i) optimistic views on the size and speed of the uninsured deposit outflows that might occur in a phase of distress, (ii) a lack of supervisory oversight, and (iii) the failure of investors to effectively exercise market discipline until it was too late. In contrast, Credit Suisse was designated a global systemically important bank and hence subject to the entire Basel III framework. It was known to have suffered management and asset quality problems dating back to well before March 2023, but its supervisors were not effective in enforcing recovery until it was too late.

Even under a well-developed set of regulatory requirements, proper risk management by the individual banks and prompt detection of trouble and corrective interventions by supervisors remain crucial for preventing disorderly failures triggered by deposit runs. Besides the contribution of, and interaction between, standard prudential tools such as capital and liquidity requirements, and setting up credible deposit insurance schemes and resolution frameworks, the holistic approach also means considering (i) ways for authorities to encourage earlier interventions in troubled banks (promoting their effective recovery before liquidation or resolution becomes the only way out) and (ii) alternatives to contain uninsured deposit withdrawals from banks (which can occur at an alarmingly higher speed than in the past, especially if the depositor base is concentrated).

The problems witnessed in the US banking industry in March 2023 had elements in common with the savings and loans crisis of the 1980s. On that occasion, an incorrect supervisory response exacerbated the crisis and added to its final cost (Shoven et al. 1992, Moysich 1997). The banks that failed in March 2023 may have been fundamentally insolvent at the time their runs occurred. However, there is widespread agreement that more timely supervisory intervention would have been beneficial. In particular, it would have helped to contain losses and prevent the messy collapses that raised fears of system-wide panic and pushed authorities into taking support measures such as temporarily extending blanket guarantees on bank deposits (Admati et al. 2023).

At present, supervisors have few tools to use if uninsured deposit withdrawals from a viable bank escalate. Even banks with a valuable deposit franchise, limited latent banking book losses, and a viable business model may suffer a run that threatens their survival. Activating ad hoc extended guarantees as a measure of last resort (as US authorities did) may contain contagion but raises significant concerns in terms of moral hazard. Alternatives would include acting pre-emptively via bank recovery tools such as early recapitalisation based on contingent convertible debt. Additionally, it might be worth considering whether there would be alternative ways to reduce uninsured deposit withdrawals in periods of distress.

The bank failures observed in March 2023 revived old debates about policy options addressing the fragility inherent in uninsured deposit funding, covering multiple aspects of the current framework, including liquidity requirements and the supervision of banks’ liquidity positions, and more structural changes to banks’ business models. In a related column (Beck et al. 2024b), as well as in our recent ASC report, we review an extensive list of options, paying specific attention to (i) their likely effect on the allocation of potential losses across agents, (ii) their implications for risk-taking, (iii) their effectiveness in reducing bank funding fragility, and (iv) their likely impact on the cost of intermediation. We also consider the main challenges to the implementation of the different options, as well as their credibility and complexity.

References

Acharya, V, A Das, N Kulkarni, P Mishra and N Prabhala (2023), “Deposit and credit reallocation in a banking panic: the role of state-owned banks”, NBER Working Paper 30557.

Admati, A, M Hellwig and R Portes (2023), “When will they ever learn? The US banking crisis of 2023”, VoxEU.org, 18 May.

Admati, A, M Hellwig and R Portes (2023), “Credit Suisse: too big to manage, too big to resolve, or simply too big?”, VoxEU.org, 8 May.

Anginer, D, A Demirgüç-Kunt and M Zhu (2014), “How does deposit insurance affect bank risk evidence from the recent crisis”, Journal of Banking & Finance 48: 312-321.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2023), Report on the 2023 banking turmoil, October.

Beck, T, V Ioannidou, E Perotti, A Sánchez Serrano, J Suarez and X Vives (2024a), Addressing banks’ vulnerability to deposit runs: revisiting the facts, arguments and policy options, European Systemic Risk Board, Report of the Advisory Scientific Committee No. 15, August.

Beck, T, V Ioannidou, E Perotti, A Sánchez Serrano, J Suarez and X Vives (2024b), "Addressing banks’ vulnerability to runs, part 2: Policy options", VoxEU.org, 10 October.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2023), Review of the Federal Reserve’s supervision and regulation of Silicon Valley Bank, April.

Drechsler, I, A Savov and P Schnabl (2021), “Banking on deposits: maturity transformation without interest rate risk”, Journal of Finance 76(3): 1091-1143.

HM Treasury (2009), “The nationalisation of Northern Rock”, March.

Honohan, P (2023), “Lessons from missing the signals of failing banks”, VoxEU.org, 26 May.

Ioannidou, V and M F Penas (2010), “Deposit insurance and bank risk-taking: Evidence from internal loan ratings”, Journal of Financial Intermediation 19(1): 95-115.

Iyer, R, T L Jensen, N Johannesen and A Sheridan (2019), “The distortive effects of Too Big To Fail: evidence from the Danish market for retail deposits”, Review of Financial Studies 32(12): 4653-4695.

Iyer, R and M Puri (2012), “Understanding bank runs: the importance of depositor-bank relationships and networks”, American Economic Review 102(4): 1414-1445.

Martin, C, M Puri and A Ufier (2024), “Deposit inflows and outflows in failing banks: the role of deposit insurance”, Journal of Finance, forthcoming.

Matta, R and E Perotti (2024), “Pay, stay or delay: how to settle a run”, Review of Financial Studies 37(4): 1368–1407.

Moysich, A (1997), “The Savings and Loan crisis and its relationship to banking”, in Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, History of the Eighties – Lessons for the Future, Volume I, Chapter 4, pp. 167-188.

Rochet, J-C and X Vives (2004), “Coordination failures and the lender of last resort: was Bagehot right after all?”, Journal of the European Economic Association 2(6): 1116-1147.

Rose, J (2023), “Understanding the speed and size of bank runs in historical comparison”, Economic Synopses, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Issue 12, pp. 1-5.

Shoven, J, S Smart and J Waldfogel (1992), “Real interest rates and the Savings and Loan crisis: the moral hazard premium”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 6(1): 155-167.

Suarez, J (2023), “Addressing interest rate risk when banking on deposits: a simple framework”, mimeo.

Swiss Financial Market Supervisory Authority (FINMA) (2023), Lessons learned from the CS crisis, December.