The banking turmoil in March 2023 was the most significant system-wide banking stress since the global crisis in terms of scale and scope (Basel Committee on Banking Supervision 2023). In our related column (Beck et al. 2024a) and in a recent report of the Advisory Scientific Committee (ASC) of the European Systemic Risk Board (Beck et al. 2024b), we review the role played by deposit funding in the EU financial system and the academic literature on bank runs and interest rate risk.

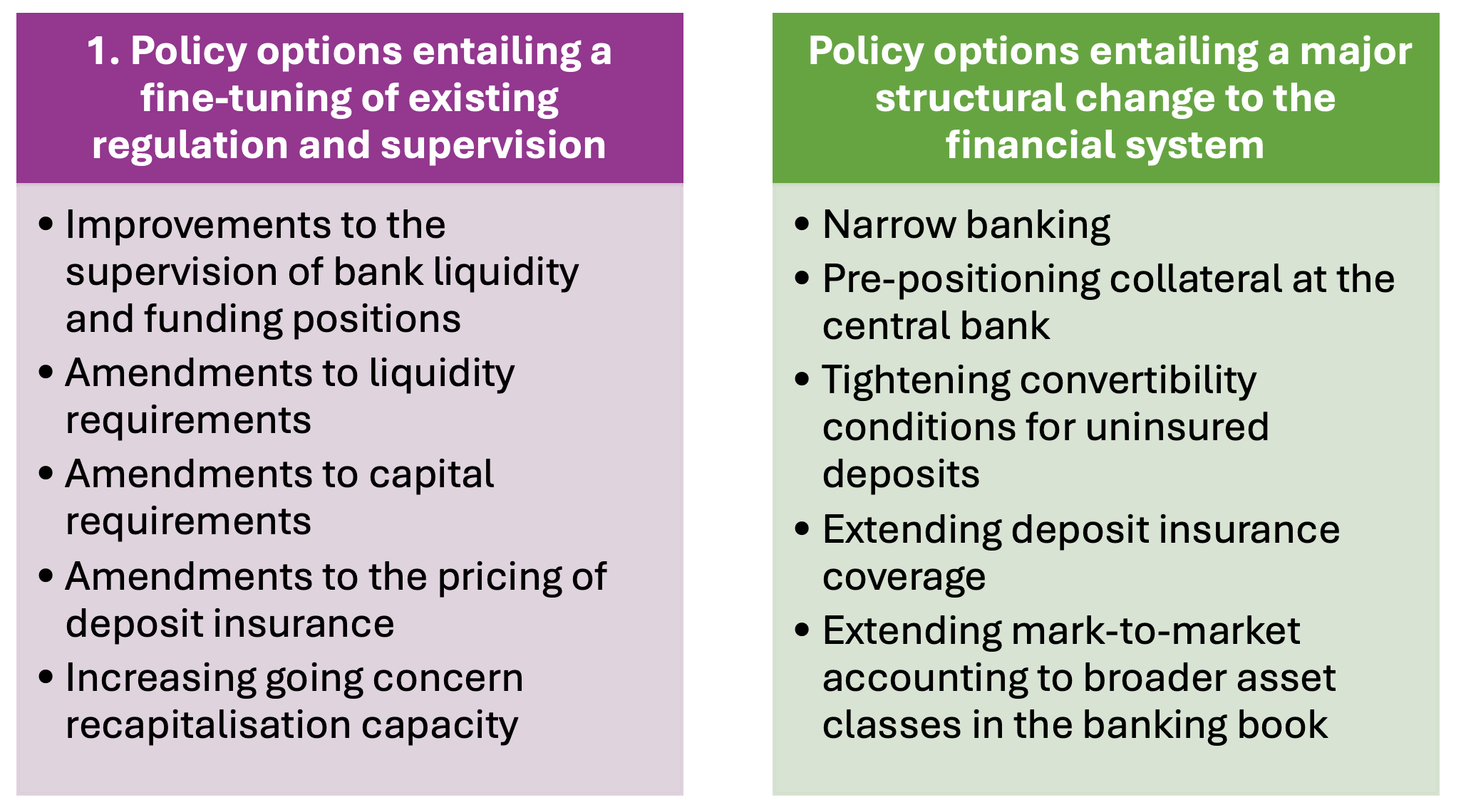

In this column, we discuss, from an academic perspective, a range of possible policy options that were mentioned in the aftermath of the banking turmoil in March 2023. Our starting point is a full and sound implementation of Basel III global standards. We order the policy options into two categories (Figure 1). The first category includes options that could be further considered without major structural changes to the current regulatory and supervisory framework, and which might be implemented as adjustments within the margins of discretion of Basel III. The second category includes those with policy options that would entail a deeper structural transformation of the institutional setup or of the banking industry.

Figure 1 Policy options to address bank funding vulnerabilities

Source: Beck et al. (2024).

In the following paragraphs, we briefly describe each category. Beck et al. (2024) offer a more detailed account of each policy, paying specific attention to (i) how each policy option affects the allocation of potential gains or losses across agents, (ii) the implications of each option for risk-taking, (iii) the effectiveness of each option in reducing bank funding fragility, and (iv) the likely impact of each option on the cost of intermediation. For related discussions on policy lessons from the 2023 banking turmoil, see Dewatripont et al. (2023) and Acharya et al. (2024).

Policy options entailing a fine-tuning of existing regulation and supervision

First, the bank runs in the US in March 2023 provided evidence of the increased speed with which deposits can move across banks and the role of social media and digital payment channels in accelerating these runs. They also showed that concerns about triggering runs lead to regulatory forbearance as supervisors are reluctant to act in a timely manner. Timely intervention by microprudential authorities would require increased frequency of reporting by banks of their liquidity positions, which is currently on a monthly basis in the EU (with the possibility for the microprudential supervisor to increase the reporting frequency on an ad hoc basis). Further granularity of the supervisory information related to the concentration of uninsured funding would also be useful. Moreover, the fact that the last published capital ratios of Silicon Valley Bank and Credit Suisse remained above the regulatory minima, at a time when they were failing, suggests the need to incorporate market-based information into the (confidential) supervisory assessment of banks and as input to timely intervention.

Second, a consequence of the striking speed of the runs observed in March 2023 relates to the way the risk of deposit outflows is considered in the computation of the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), even if the LCR is not designed to cover all tail events. Currently, the LCR is computed assuming outflow rates of 3% and 10% for stable (i.e. insured) and less stable (i.e. uninsured) household deposits respectively over a period of 30 days, while outflow rates for corporate deposits are estimated in the range from 5% to 40%. In addition, in view of the vulnerability stemming from the concentration of uninsured depositors, regulators and supervisors could consider introducing concentration limits on the funding side (for uninsured deposits or similarly flighty liabilities), similarly to the large exposures regime. Another measure to ensure a timely recognition of distress would require that all debt securities qualifying as liquid assets be measured at fair value in the financial statements. While this would not affect the LCR calculation, it seems illogical to classify some securities as ‘held-to-maturity’ for accounting purposes and at the same time consider them as available to cover sudden liquidity needs.

Third, turning to amendments to capital requirements, it is obvious that higher capital buffers increase bank resilience in the face of a materialisation of various risks, but there are trade-offs. Indeed, a 'one size fits all' solution is not optimal, because the capital ratio necessary to protect the most vulnerable banks may be excessively high for (and unduly penalise) those which are less vulnerable. In line with the view that a 'one size fits all' solution is not optimal, interest rate risk in the banking book is currently addressed under Pillar 2. However, in addition to ensuring a full and faithful implementation of the whole Basel III framework, there may be room for a more explicit and dedicated treatment of interest rate risk in the banking book or funding fragility risks in Pillar 2. A possibility would be to establish a more direct link between the results of regular interest rate risk-specific stress tests and corrective actions (e.g. in the form of capital and liquidity planning and potential restrictions on the maximum distributable amount).

Fourth, the pricing of deposit insurance could be amended to make it (even) more risk-based. Discussions about the pricing of deposit insurance typically combine two perspectives: funding (to finance the activities of deposit insurance schemes) and incentives (to raise insured deposits and, if risk-based, the accompanying risk-taking). In the EU, banks’ contributions to deposit guarantee schemes are based on the amount of covered deposits and the degree of risk incurred by each bank. According to EBA Guidelines (European Banking Authority 2023a), a bank’s contribution should be adjusted by the risk posed by the institution, measured by an aggregate risk weight based on capital, liquidity and funding, asset quality, business model and management, and potential losses for the deposit guarantee scheme. Following their successful implementation across the EU and the experience gained over the first few years, the EBA Guidelines may undergo limited enhancements to increase their risk-based component.

Fifth, in all cases of bank distress during 2023, delays in supervisory intervention led to forbearance over poor capitalisation and weak risk controls, resulting in even larger losses. Strengthening bank resilience and the chance of recovery may require increasing going concern recapitalisation capacity. Offering new powers to supervisors to intervene timely in weak but potentially viable banks may reassure depositors and prevent the escalation of outflows. In this regard, evaluating a bank deposit franchise and business model next to its book equity would help assess whether a troubled bank is viable and able to recover, or is actually not viable and should be moved into resolution. Moreover, a more credible implementation of convertible (CoCo) bonds would restore supervisory credibility for preventive intervention and have a disciplining effect on risk creation. Activating the conversion of CoCo bonds by means of a regulatory trigger after a thorough stress test, a higher trigger based on risk-weighted assets or a trigger determined by market prices could therefore increase their usefulness during episodes of banking stress (see also Calomiris and Herring 2013, Martino and Perotti 2024).

Policy options entailing a major structural change to the financial system

First, narrow banking proposals are usually brought to the fore after banking crises and may take several forms, from subjecting banks to a 100% reserve requirement (that is, fully backing their deposits with central bank reserves) to milder forms equivalent to imposing stricter versions of existing liquidity requirements. The strongest argument against imposing a full version of narrow banking by regulation is that it would force a separation between the deposit taking and loan making activities of banks or, more broadly, eliminate their socially valuable maturity and liquidity transformation functions. A likely effect would be to shift most lending and all credit risk to less regulated shadow banks (Vives 2016). It would also diminish banks’ role in the transmission of monetary policy.

Second, a related alternative to narrow banking is to require banks to have their flighty (uninsured) deposit funding fully backed (after applying appropriate haircuts) by collateral prepositioned at a central bank discount facility. This idea was first formulated as the ‘pawnbroker for all seasons’ by King (2016). Rather than eliminating liquidity risk, banks would use collateral to obtain liquidity from the central bank, enabling them to cope with deposit outflows. As in the case of narrow banking, a full implementation of this alternative could be a substitute for deposit insurance and liquidity requirements. A fractional reserve approach would allow banks to remain involved in lending activities, albeit on a reduced scale (as risky private loans would be refinanced at a discount). Under this arrangement, central banks’ collateral frameworks would play a central role in determining the provision of bank credit to the economy, potentially interfering with central banks’ current core competencies regarding price stability and financial stability.

Third, contingent measures such as automatic charges triggered by high outflows would slow down withdrawals and contain self-reinforcing expectations of rapid escalation into a run (Perotti 2023). Such measures could act as market stabilisers and buy precious time for authorities. In a run, most withdrawals do not reflect a need for immediate liquidity but a fear of not being paid in full if the bank becomes insolvent. In this context, early withdrawers impose an externality on late withdrawers, since the bank may become insolvent (and unable to pay the remaining deposits in full) once a sufficient number of depositors have withdrawn their deposits. Similar concerns arise for investors in the money market fund sector, where regulators have favoured in recent years contingent charges (or swing pricing), to be automatically activated and quantitatively adjusted to the size of the outflows taking place. Imposing temporary redemption charges on uninsured deposit outflows would directly reduce run incentives and may also shift expectations of further withdrawals by others, avoiding escalation driven by fear of dilution rather than solvency concerns. The strongest argument against these measures is that departing from the par value conversion of uninsured deposits would entail a fundamental change in the nature of this key money-like saving instrument.

Fourth, following the banking turmoil in March 2023, it has been suggested to extend the scope of deposit insurance to all deposits, regardless of their amount. The existing literature suggests that while deposit insurance can play a key stabilising role in times of crisis, it can also undermine financial stability by encouraging the build-up of risk in the financial system (Anginer et al. 2014). Extending deposit insurance to all deposits will further increase the volume of large deposit accounts on bank balance sheets (attracting funds now outside the banking system) and will remove any incentive for depositors to question the stability and risk profile of the bank. Furthermore, a significant extension of deposit coverage is likely to increase opposition to creating a common deposit insurance scheme in the euro area, as it would raise concerns about the socialisation of losses due to excessive risk-taking.

Last but not least, the market turmoil in the US in March 2023 reignited the discussion on the benefits of applying mark-to-market accounting to as many bank assets as possible. This reiterates on the old debate in accounting and prudential circles on the benefits and costs of fair value versus amortised cost (or ‘historical cost’) in the measurement of financial assets (see European Systemic Risk Board 2017). Overall, in the current debate there is no consensus on the benefits of promoting full (or as full as possible) mark-to-market accounting in banking. However, there may be room for more targeted changes. For instance, as outlined by Cecchetti and Schoenholtz (2023), there could be room for fine-tuning current accounting rules to ensure that changes in the market value of securities in banks’ balance sheets are reflected in the banks’ capital requirements.

Concluding remarks

To sum up our views on the policy proposals above, we do not regard proposals to move towards a full version of narrow banking or an untargeted expansion of deposit insurance coverage as desirable, while proposals of redemption gates and the pre-positioning of collateral require further careful consideration of the pros and cons. Moving to a full narrow banking system would shift intermediation activities outside the regulated banking sector, and an expansion of deposit insurance coverage would involve high costs and a reduction in market discipline.

While there are arguments in favour of contingent measures to avoid the escalation of withdrawals into runs, they would fundamentally change the nature of deposits as money-like instruments and thus require a very careful assessment. Similarly, the proposal of prepositioning collateral at the central bank must be holistically assessed, taking into account issues related to ‘safe assets’ and central bank policies, as well as their impact on the maturity transformation provided by banks.

On the other hand, we believe that three proposals could be implemented relatively quickly and would potentially increase banks’ liquidity resilience, reduce their incentives to take risks aggressively, and provide supervisory authorities with the necessary information and possibly time to intervene in fragile banks. The proposals refer to (i) amendments to liquidity requirements, (ii) enhancements to the supervision of banks’ liquidity and funding positions, and (iii) improving how funding fragilities are incorporated into the computation of Pillar 2 liquidity and capital guidance.

Finally, there are proposals that would require deeper analytical efforts or legislative changes and are thus only feasible in the medium term. Changes to the pricing of deposit insurance would require data and modelling work to design better risk-based premiums. Changes to Pillar 1 capital requirements would require global regulatory agreements to be reopened and would thus only be feasible in the medium to long term, unless EU authorities decided to top up the global minimum requirements. Contingent measures to ensure credible recapitalisation and favour recovery over resolution are desirable, with the specific intent to overcome the current bias for forbearance. They could be included in current discussions on the EU recovery and resolution frameworks.

References

Acharya, V, E Carletti, F Restoy and X Vives (2024), “Banking turmoil and regulatory reform”, VoxEU.org, 7 June.

Anginer, D, A Demirgüç-Kunt and M Zhu (2014), “How does deposit insurance affect bank risk evidence from the recent crisis”, Journal of Banking & Finance 48: 312-321.

Basel Committee on Banking Supervision (2023), Report on the 2023 banking turmoil.

Beck, T, V Ioannidou, E Perotti, A Sánchez Serrano, J Suarez and X Vives (2024a), “Addressing banks’ vulnerability to runs, part 1: Facts, arguments, and policy challenges”, VoxEU.org, 8 October.

Beck, T, V Ioannidou, E Perotti, A Sánchez Serrano, J Suarez and X Vives (2024b), “Addressing banks’ vulnerability to deposit runs: revisiting the facts, arguments and policy options”, European Systemic Risk Board, Report of the Advisory Scientific Committee No. 15, August.

Calomiris, C and R Herring (2013), “How to design a contingent convertible debt requirement that helps solve our Too-Big-to-Fail problem”, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 25(2): 39-62.

Cecchetti, S and K Schoenholtz (2023), “Making banking safe”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18302.

Dewatripont, M, P Praet and A Sapir (2023), “The Silicon Valley Bank collapse: Prudential regulation lessons for Europe and the world”, VoxEU.org, 20 March.

European Banking Authority (2023a), “Guidelines (revised) on methods for calculating contributions to deposit guarantee schemes under Directive 2014/49/EU repealing and replacing Guidelines EBA/GL/2015/10”, February.

European Banking Authority (2023b), Report on deposit coverage in response to European Commission’s call for advice, December.

European Systemic Risk Board (2017), “Financial stability implications of IFRS 9”, July.

King, M (2016), The end of alchemy, Little, Brown Book Group, London.

Martino, E and E Perotti (2024), ”Containing runs on solvent banks: prioritizing recovery over resolution”, CEPR Policy Insight No. 127.

Perotti, E (2023), “Learning from Silicon Valley Bank’s uninsured deposit run”, VoxEU.org, 5 May.

Vives, X (2016), Competition and stability in banking. The role of regulation and competition policy, Princeton University Press.