Global supply chains have long been recognised for their role in enhancing cost efficiencies (Antràs and Chor 2022). However, the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic and ongoing geopolitical tensions have revealed their fragility. At the same time, a significant debate has emerged surrounding the drivers of the recent bout of inflation. While highlighting the traditional demand-side influences coming from stimulus packages and rising consumer demand, some scholars recognise that an important role was played by supply chain disruptions, logistical constraints, and production halts (Bernanke and Blanchard 2023). In the media, some commentators have suggested that firms have taken advantage of supply chain disruptions to raise prices, talking about ‘greedflation’. However, in the academic discourse, the exact source of this increase in market power remains unclear.

The unequal impact of supply chain shortages

In our paper (Franzoni et al. 2024), we provide a link between supply chain shortages and the observed increase in firms’ market power. We show that these disruptions impacted firms heterogeneously as a function of their size in the relevant industry. In our analysis, we find that following the supply chain shortages, the larger firms in an industry gained a competitive edge over smaller competitors. These industry champions were better equipped to navigate the disruptions due to their diversified supplier networks and greater bargaining power with their suppliers, who provided preferential deliveries when shortages occurred.

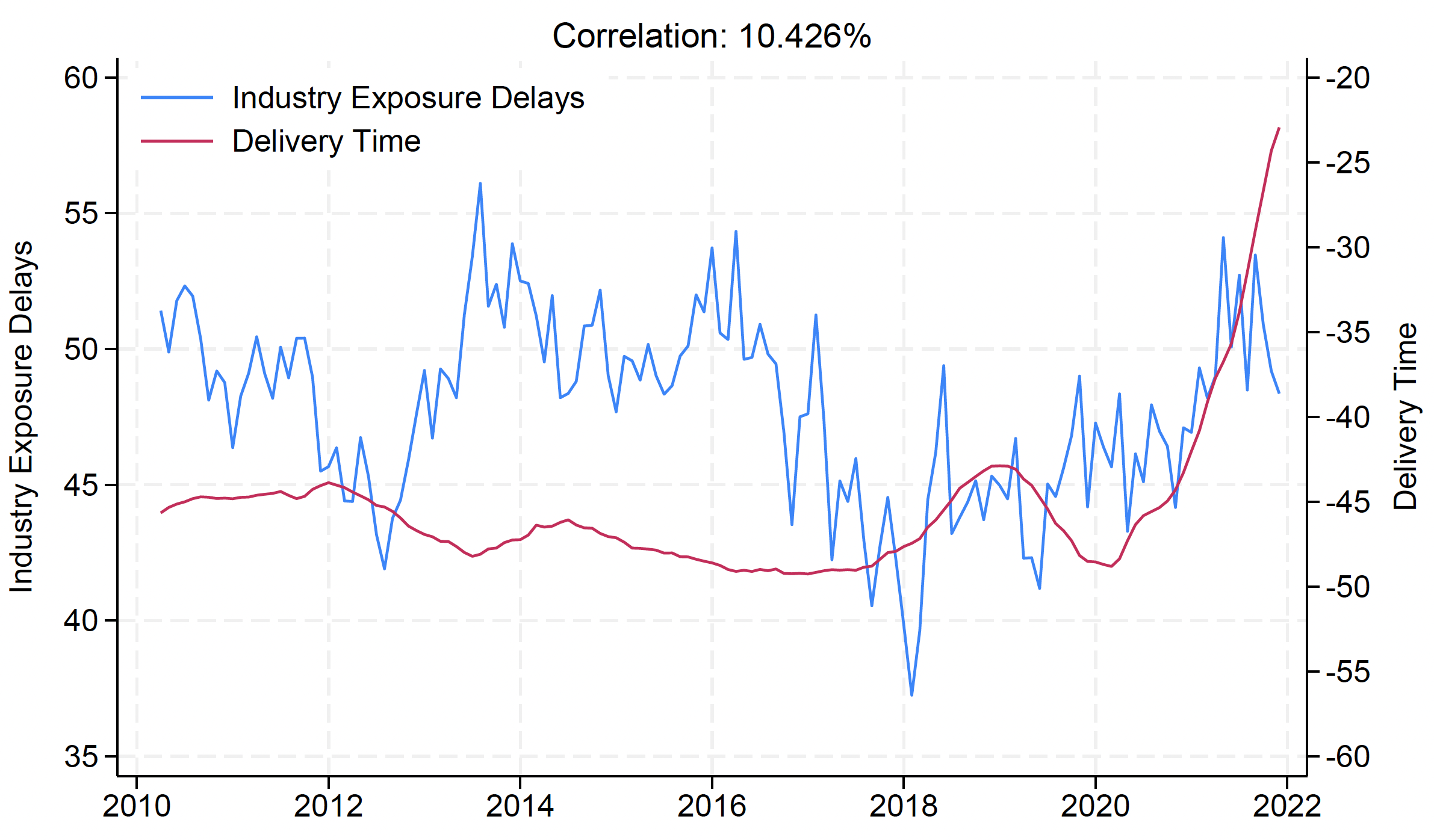

Figure 1 from our research highlights the time series of supply chain shortages, measured using both industry exposure to port congestions (Industry Exposure Delays, blue line) and supplier delivery times (red line). The former measure is derived from Bills of Lading (BoL) data, which provides detailed information on maritime shipping volumes for imports into the US from around the world. The latter is the supplier delivery times S&P Global Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI), which summarises at the industry-region level the time it takes for firms to receive the goods they have ordered. As seen in the figure, there was a significant increase in supply chain disruptions in 2021, coinciding with the peak of the Covid-19 pandemic, which strained firms across the globe. This increase in delivery delays underscores the magnitude of the disruption experienced by firms during this period.

Figure 1 The time series of supply chain shortages

Notes: This figure plots the time series of the average of our proxies for supply chain disruption across US industries. We report Industry Exposure Delays on the left y-axis and Delivery Time on the right y-axis.

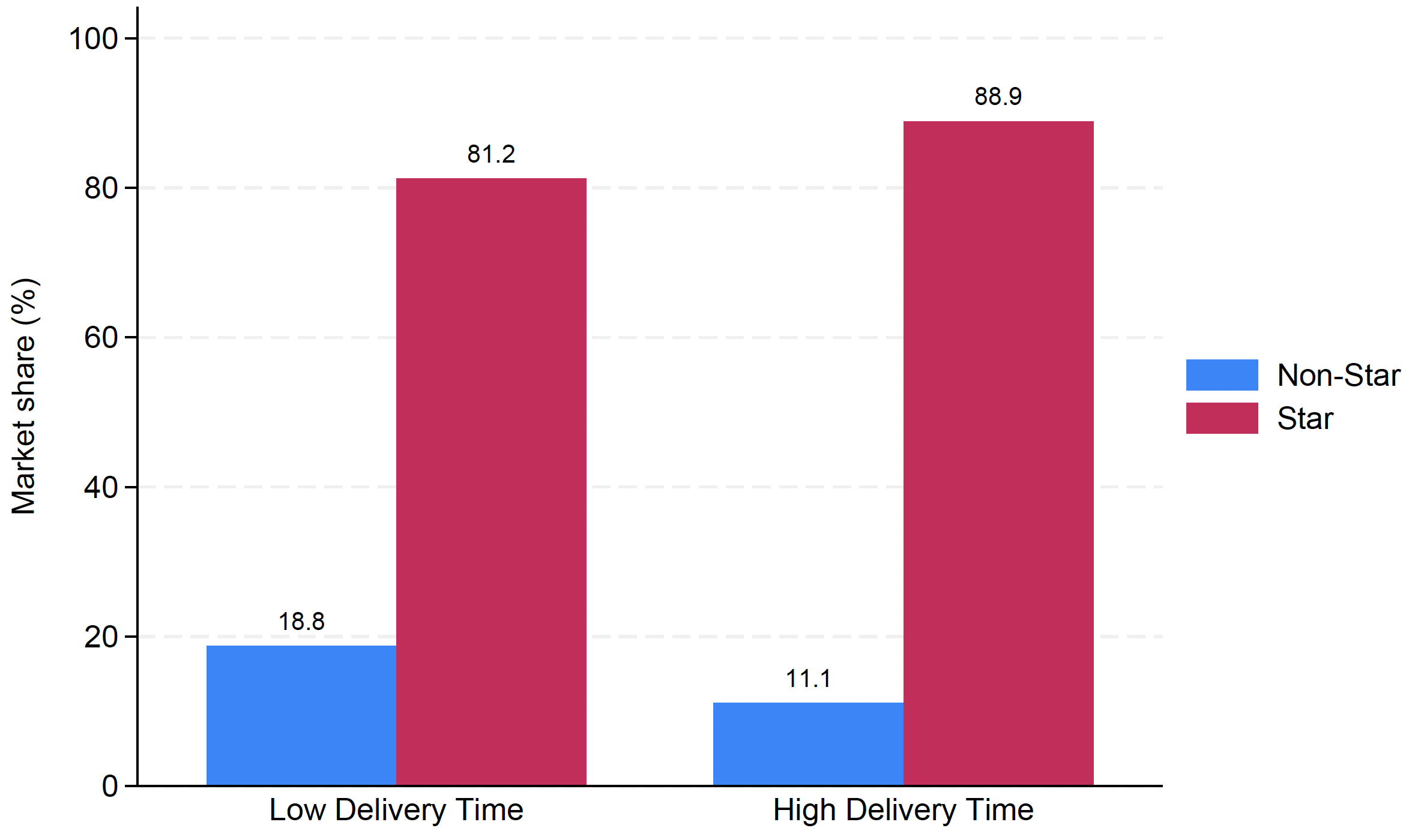

Our findings suggest that, in this context, larger firms proved more resilient. Figure 2 shows that superstar firms were able to increase their market share during periods of high delivery times at the expense of smaller firms. Specifically, during periods of supply-chain disruptions, superstar firms held 88.9% of the market share, up from 81.2% during calmer periods.

Figure 2 Market share and delivery time

Notes: This figure plots the average total market share of Star and Non-Star firms in periods of low and high delivery time. At the top of each bar we report the percentage market share for each group.

The mechanism behind large firms’ resilience

Studying the channel behind these gains in market share, we observe that larger firms received preferential treatment from suppliers when shipping capacity was constrained. For instance, using maritime shipment data, we find that during supply chain bottlenecks, the deliveries of inputs to large firms were less negatively impacted. This advantage was further compounded by the fact that larger firms often sourced from larger suppliers, who were also less affected by the disruptions.

The consequence was a widening gap in production costs between large and small firms. While smaller firms struggled to maintain their operations, large firms increased their market share and profitability. This improvement in competitive edge was also reflected in higher stock returns.

The mechanism proposed in our paper provides an equilibrium explanation for why large firms’ market power and profits have increased in the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic. The term ‘greedflation’ has gained traction in the media and political discourse, with some commentators arguing that large corporations used supply chain disruptions as an excuse to increase prices unjustifiably. Our paper provides an empirical foundation for understanding how supply chain shortages can reduce competition and allow firms with significant market power to raise prices. However, we do not suggest that these price hikes are purely opportunistic. Rather, we emphasise the structural advantages large firms have in navigating supply chain bottlenecks, which can lead to a less competitive environment and higher markups.

Inflation: More than just a cost pass-through

One of the most significant outcomes of this shift in market dynamics is its contribution to inflation. While much of the inflationary pressure during the post-pandemic recovery has been attributed to cost pass-through effects—where firms raise prices to cover higher production costs—our research suggests that there is more at play. In industries dominated by large firms, price hikes were not solely a reflection of higher costs, but also an indication of increased market power driven by the cost advantages that the large firms enjoyed over their competitors.

These effects were more pronounced in industries where a few large firms already dominated their competitors. In these industries, concentration further increased due to the shortages and prices spiked more sharply than in industries where firms are homogenous in size and, consequently, similarly affected by the shortages. We also find that in industries that are ex-ante more concentrated, supply chain shortages are associated with larger drops in output, indicating that market power amplifies supply shocks. These findings are in line with work by Bernanke and Blanchard (2024), who argue that supply-side shocks, such as those seen during the pandemic, can have inflationary consequences when coupled with high market concentration.

Aggregating the effect we identify across industries, we estimate that up to 23% of US inflation in 2021 can be attributed to the mechanism of supply chain-driven market concentration. The phenomenon is not isolated to the US, with similar patterns observed internationally.

Policy implications: Market power and inflation

The Covid-19 pandemic exposed how vulnerable global supply chains are and the risks they pose to both competition and price stability. As supply chain problems begin to resolve and smaller companies can more easily obtain necessary inputs, the advantage that large, dominant firms enjoy may lessen. This could lead to lower profit margins and a decrease in inflation, helping to explain why inflation has been falling without causing a recession. However, ongoing supply chain challenges, especially with rising geopolitical tensions, highlight the need for thoughtful policy responses.

Central banks, which are responsible for managing inflation, might find that their usual tools are not enough when inflation is driven by changes in market power. Simply increasing interest rates to reduce the money supply may not tackle the root problem of increased market concentration caused by supply chain issues. On the contrary, higher interest rates could make it harder for small businesses to access funds, reducing competition further and potentially leading to higher prices.

To address these problems, a comprehensive approach is necessary. This means not only improving the resilience of supply chains by diversifying sources, investing in infrastructure, and reducing dependence on single suppliers but also ensuring fair competition in the market. Looking ahead, policymakers and regulators must understand that supply chain shortages do more than temporarily slow down production—they can change the competitive landscape to favour larger firms. This shift significantly affects how inflation behaves and how much supply shocks can impact the economy. By recognising the broader economic impacts of ongoing and future supply chain disruptions, effective policies can be developed to promote fair competition, stabilise prices, and build a more resilient economy in the post-pandemic world.

References

Antràs, P and D Chor (2022), “Global Value Chains”, Handbook of International Economics 5: 297-376.

Bernanke, B and O Blanchard (2023), “What Caused the U.S. Pandemic-Era Inflation?”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 23–4.

Bernanke, B and O Blanchard (2024), “An analysis of pandemic-era inflation in 11 economies”, Peterson Institute for International Economics Working Paper 24–11.

Franzoni, F, M Giannetti and R Tubaldi (2023), “Supply Chain Shortages, Large Firms’ Market Power, and Inflation”, CEPR Discussion Paper 18574.