Life is an adventure and an important part of the journey, for many, is earning a livelihood while nurturing a family. These often occupy the same time slots and, for most, that creates conflict. Mothers often reduce their hours at work and occasionally leave employment or shift into less time-intensive jobs and firms. But a cascading often follows. Fewer hours at paid work when young generate fewer promotions later.

A large and internationally diverse literature has demonstrated that men and women have divergent earnings growth paths after the birth of a child. That conclusion is true even when they had been on the same career trajectory and also holds within couples (e.g. Johansson and Lindahl 2016, Kleven et al. 2019, Kuziemko et al. 2018).

These realities are the main parts of an important and well-explored reason why women earn less than men in the decade or more following their first birth. But, what happens to women’s work, careers, and earnings when the children grow up? That is what we explore in our recent paper (Goldin et al. 2022).

There is a moment when childcare demands lessen and women can assume greater career and workplace challenges. Do mothers earn more as a result of their increased work time, relative to men and to women who have not yet had, or will never have, children? To answer these questions, we use longitudinal data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) and observe men and women born from 1957 to 1964 as they advance to their mid-fifties.

Gender earnings gaps from the NLSY79

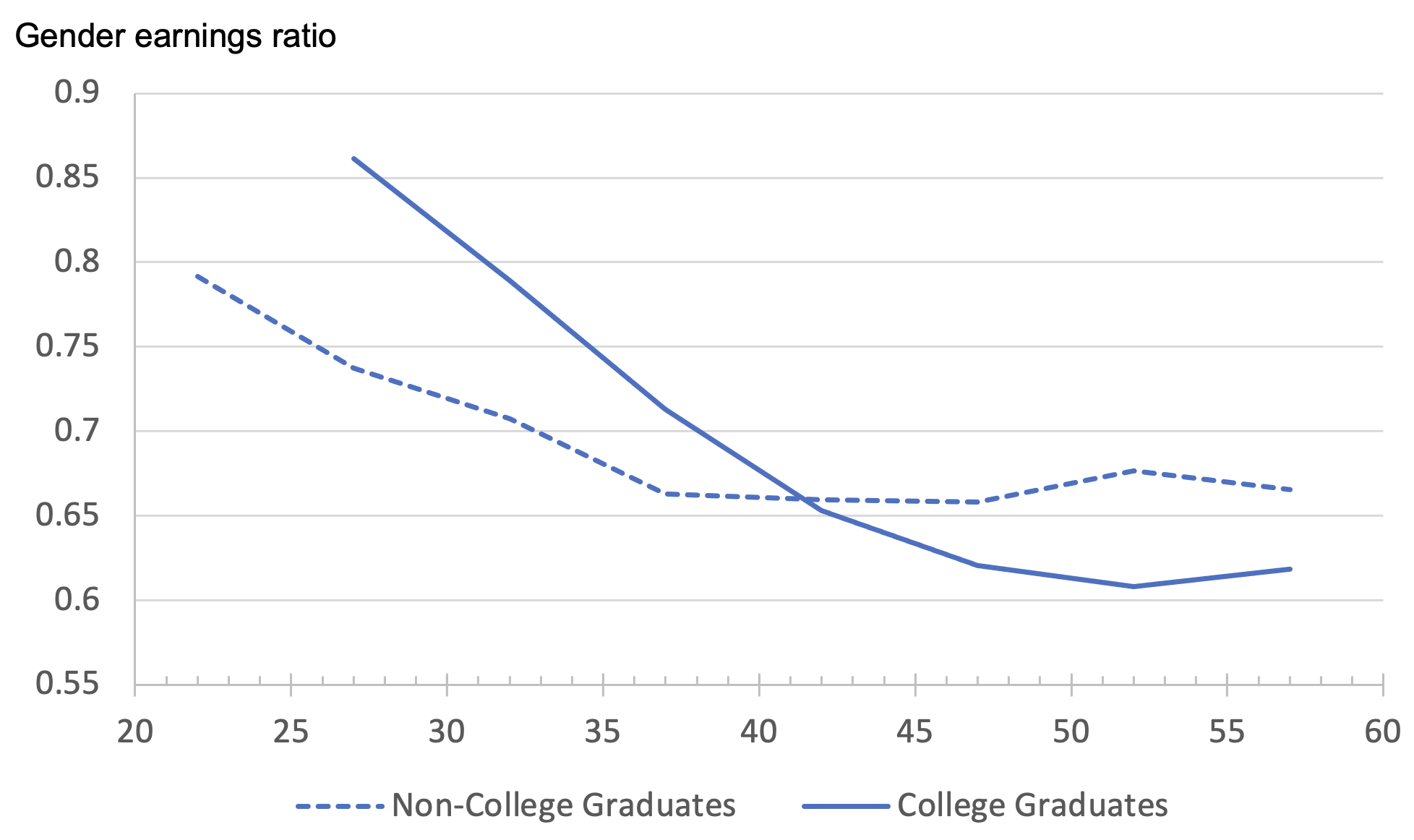

We motivate our study with Figure 1, showing the estimated gender earnings gap (ratio) by age and education, controlling for hours and weeks worked. The gender earnings ratio is initially higher for those with a college degree (solid line) than those without (dashed line). But college graduate women quickly lose out relative to college graduate men, and by their early forties, the gender earnings ratio for the two education groups switches and becomes greater for those without a college degree. College graduate women lose out relative to their male counterparts, whereas the less-educated women have earnings that remain about the same relative to less-educated men.

Figure 1 Relative annual earnings of women to men by education level: Cohorts born 1957 to 1964

Gender earnings ratio

Sources: OLS estimation from Goldin et al. (2022), tables 2a, 2b col. (2).

Notes: College graduates are those who have earned a four-year college degree by age 35, and the non-college are those who did not, but who achieved at least a high school degree by that age. Log(hours) and log(weeks) are held constant. College graduate age groups begin at ages 25 to 29; non-college graduate groups begin at ages 20 to 24. Midpoints of age groups are given.

The role of children in the gender earnings gap is investigated next, together with how differences in earnings between mothers and non-mothers, and between mothers and fathers, evolve as the children grow up and reach milestone ages.

The motherhood effect and the parental gender gap in earnings

Similar to the studies previously mentioned, we find that hours of paid work initially plummet with motherhood, more so for the college graduate group. Hours stay lower for mothers than non-mothers in the college graduate group, but increase as the youngest child begins school and eventually graduates secondary school. Hours for mothers in the non-college graduate group become virtually identical to non-mothers. Mothers increase their work time as the children grow up, but they are still behind fathers.

How do the changing work effort patterns translate to pay gaps? We next analyse how log(annual earnings) changes in an individual fixed effects framework including age group variables and their interaction with gender, work time variables (weeks and hours in logs), the number of children and the age group of the youngest all interacted with gender, and a measure of accumulated job experience. The estimation is done separately by the two education groups in Figure 1.

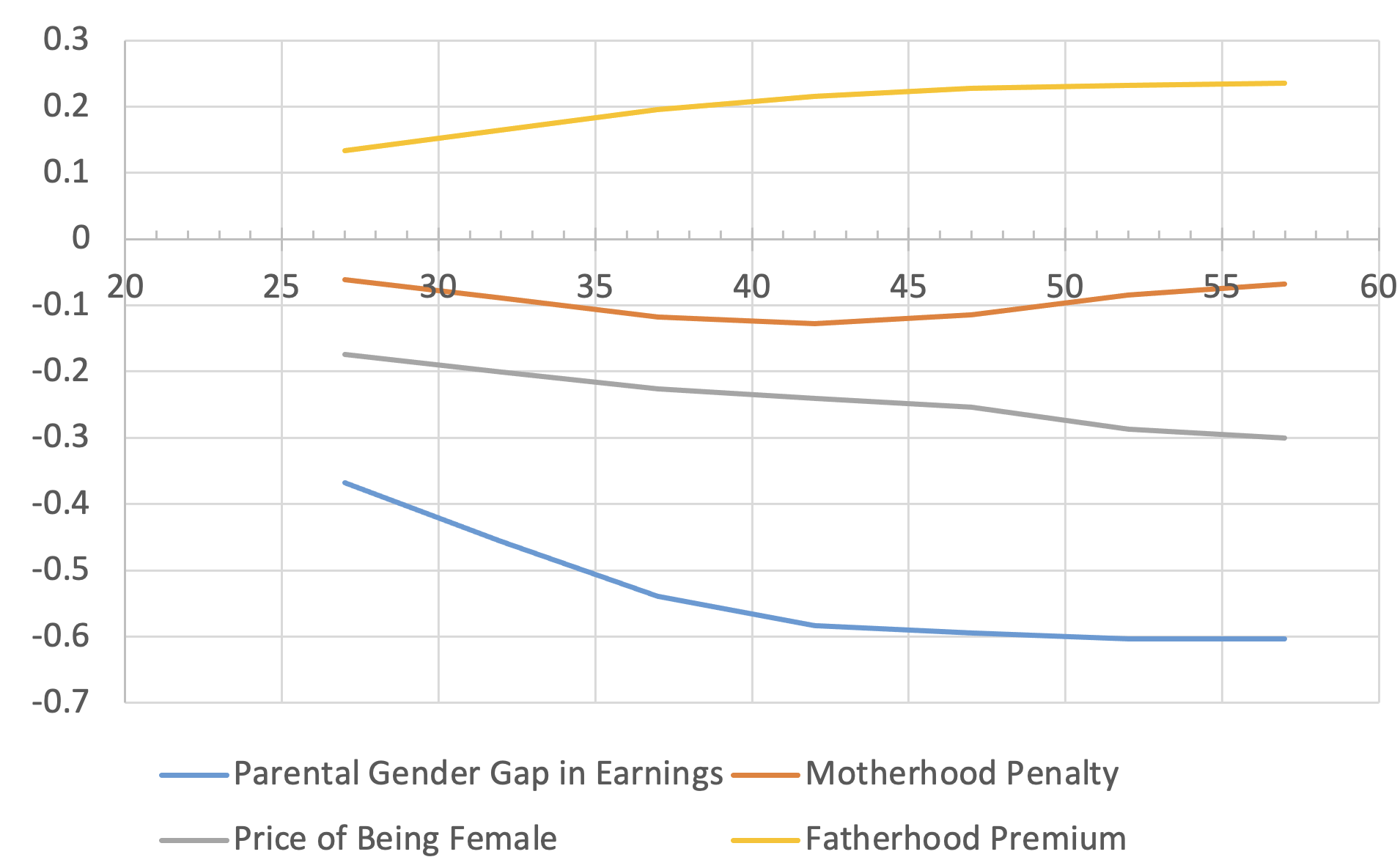

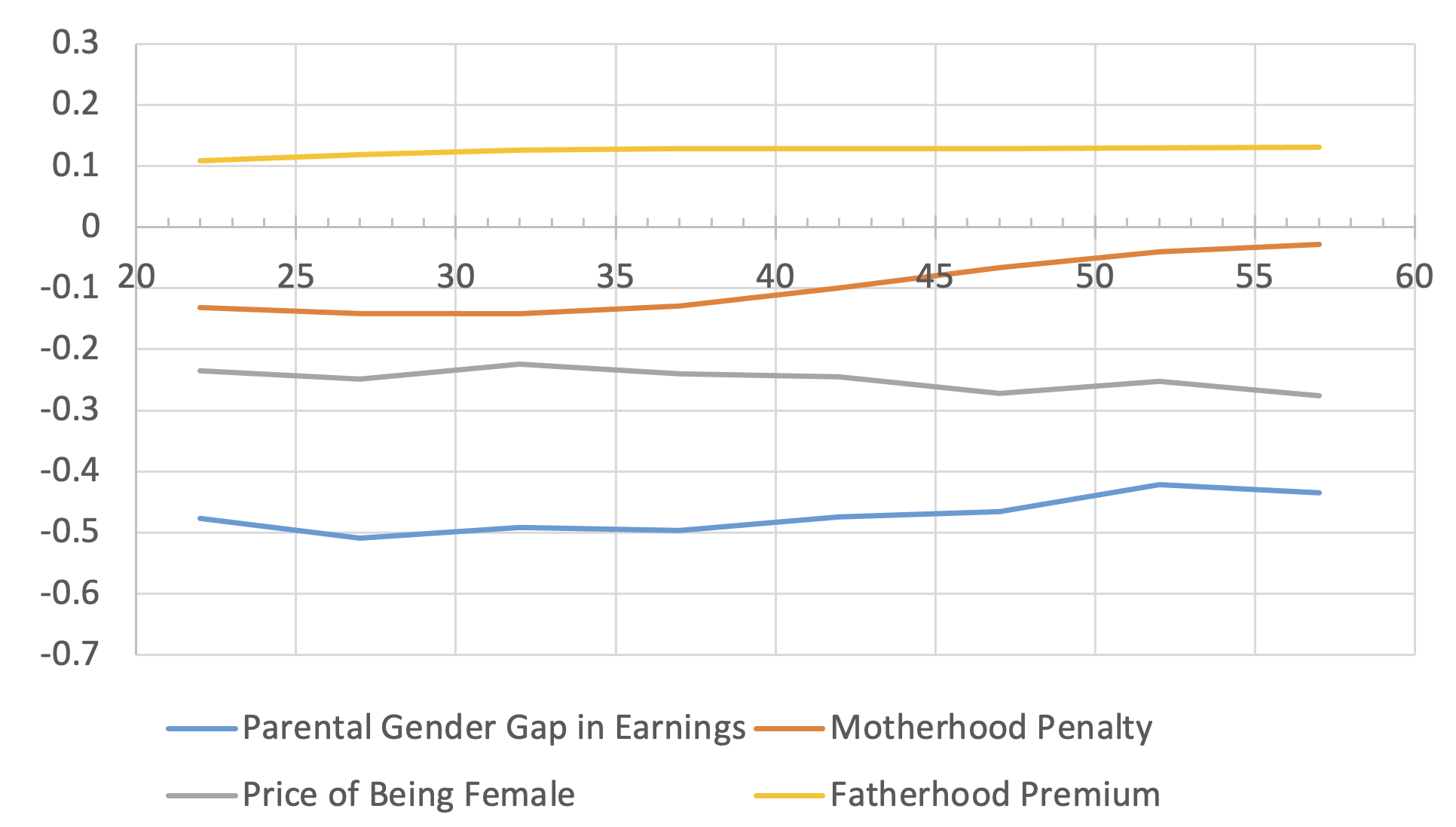

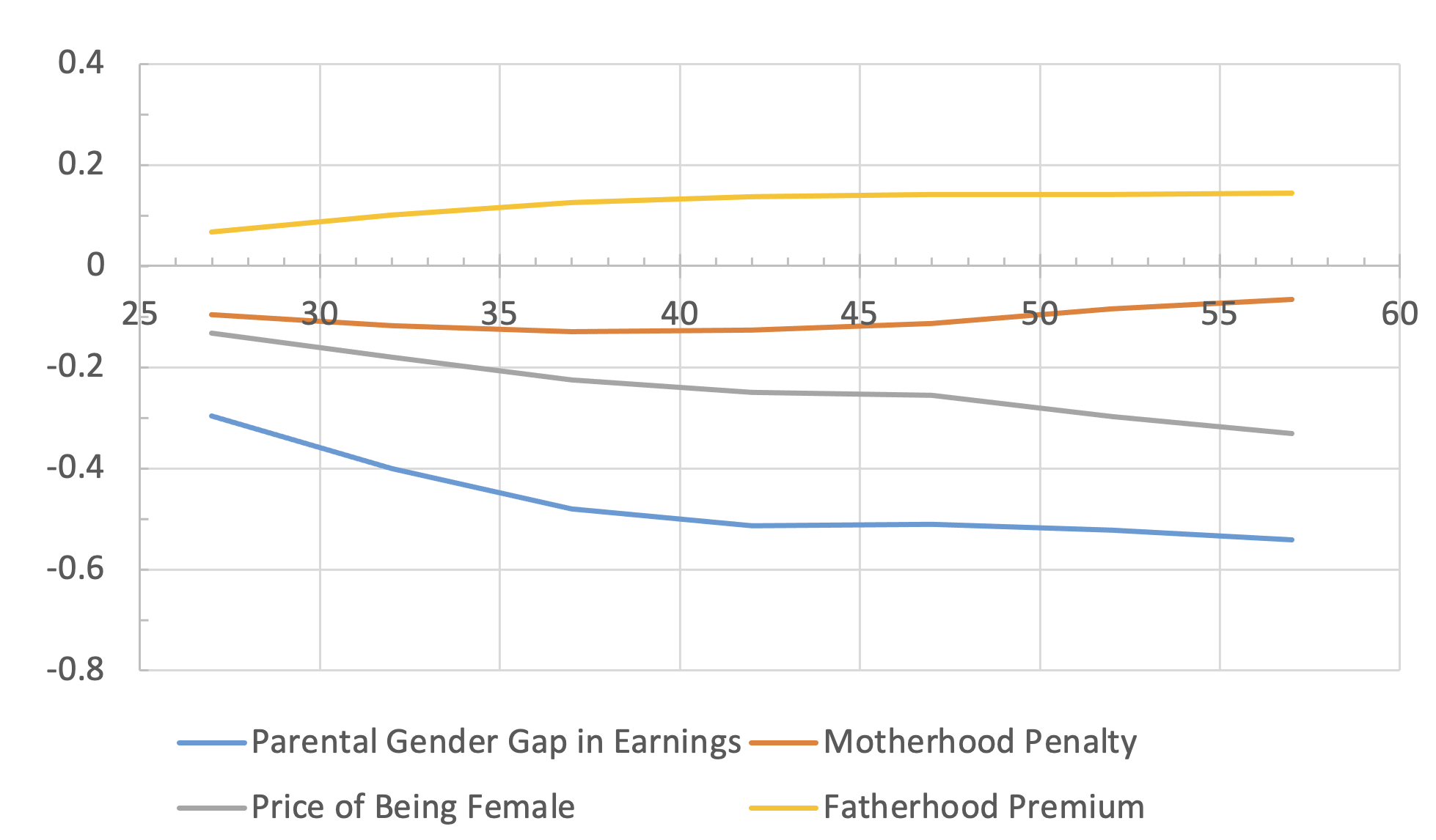

Figures 2a and 2b partition the parental gender gap (blue line) into three components: the motherhood penalty (the difference between mothers and non-mothers; orange line), the price of being female (the difference between men and women; grey line), and the fatherhood premium (the difference between fathers and non-fathers; yellow line). The full parental gender gap in earnings (blue line) varies in similar ways to Figure 1. It is greater for the less educated at first and then greater for the more educated.

Figure 2 Parental gender gap in earnings (= motherhood penalty + price of being female – fatherhood premium)

A) College graduates

B) Non-college graduates

Source: Goldin et al. (2022), table 4.

Notes: Estimates use the results from our standard individual fixed effects regression of annual earnings with age groups interacted with gender, total number of children and age group dummy of youngest child (0<3; 3<6; 6<12; 12<18; 18 plus) interacted with gender plus log(hours), log(weeks), previous five year’s work experience, and advanced degrees (for the college graduate sample). All parents are assumed to have children given by the data for women with regard to number and age of the youngest in Goldin, et al. (2022), Appendix table 1. We simulate the effects of changing the number of children and the age of the youngest by using the mean number and ages of children in the sample by gender and education.

Consider, for example, college graduate women and men at ages 35 to 39. Women with children earn 12 log points less than women without children. But a similar difference between mothers and fathers is 54 log points. What accounts for the enormous difference between the parental gender gap and the motherhood gap?

Two primary factors reveal why mothers earn far less than fathers. All college graduate women 35 to 39 years get 22.6 log points less than same age men. The remainder (now in excess of 19 log points) comes from the fatherhood premium. There may be astonishment at this finding. Not only do women earn less by their years of raising children, but men actually earn a premium.

The fatherhood premium is fairly constant across age groups for the non-college graduate group and considerably smaller after age 40. The parental gender gap in earnings is equivalently smaller.

There is a long-standing literature regarding the fatherhood premium and the male marriage premium. The literature has assessed whether fathers (or married men) earn more because they work harder after they have children (or get married) or, alternatively, whether they become fathers (or get married) when they are earning more or that various principals in the labour market (e.g., supervisors) reward fathers and married men more.

Whatever the reasons, among different sex couples, men are enabled to become fathers while continuing to advance in their careers because women disproportionately take care of the children. Mothers cut back on their paid work hours, work less demanding jobs, and earn less. But something else must be operating because women without children do worse than men with children. For men, having the children and a wife who is the caregiver is related to their earnings boost. Put simply: the motherhood penalty becomes very small as the children grow up, but the fatherhood advantage remains large and increases with age, especially among college graduates.

Exploring the fatherhood premium

What can explain the persistence of the fatherhood premium? We explore the possibility that the fatherhood premium, and its increase with age, come disproportionately from fathers who have time-intensive jobs around the moment of family formation.

We focus on college graduates since the fatherhood premium accounts for about 40% of the parental gender gap in earnings for the college graduate group but just 25% for non-college graduates.

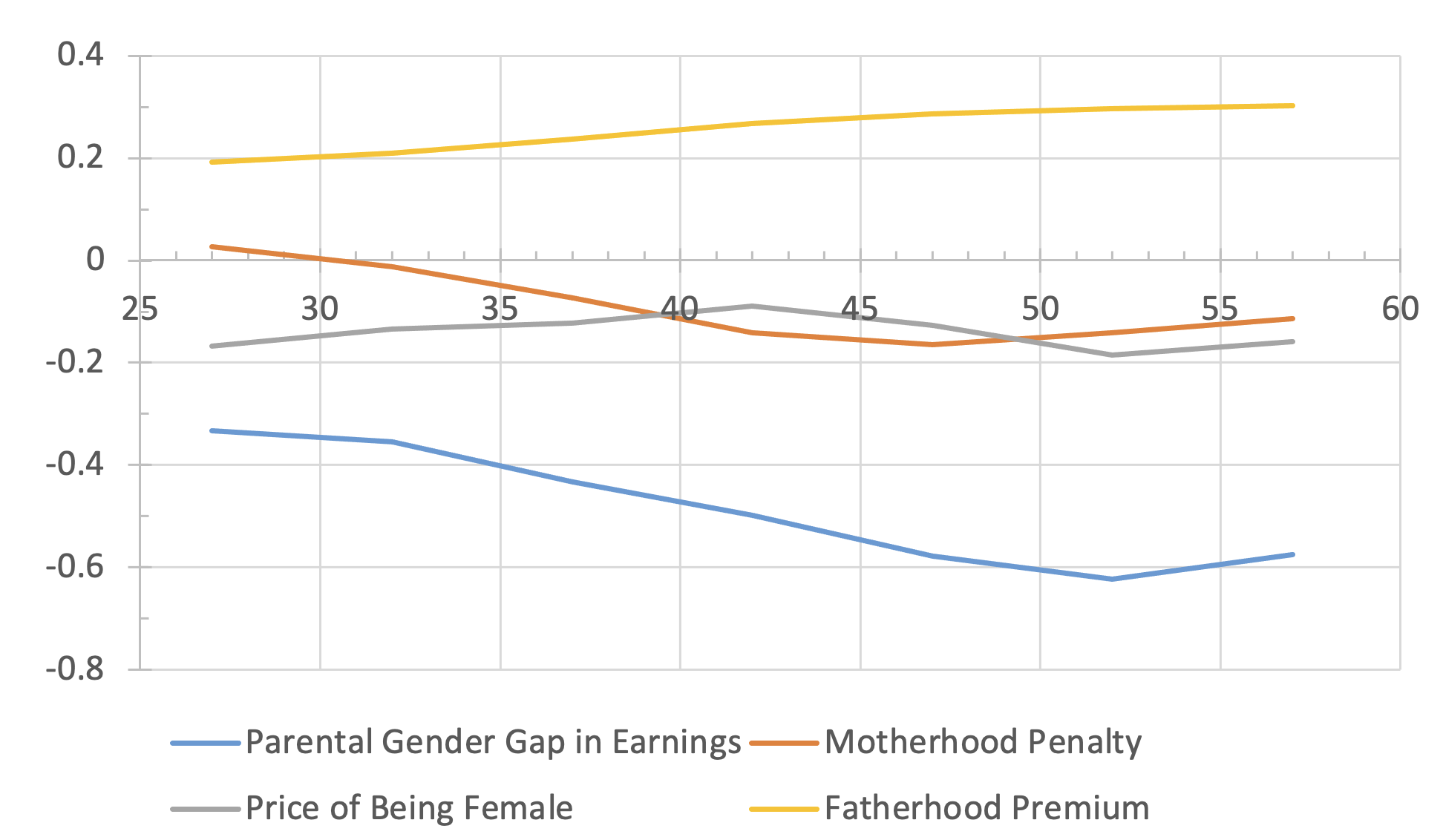

Figure 3a gives the results for those with time-intensive occupations and Figure 3b for those without. The differences are striking. The fatherhood premium for the time-intensive group (yellow line) is generally twice that for the others. The fatherhood premium for college graduates in the non-time-intensive group is the same as for non-college men. The price of being female (essentially the residual; grey line) is substantially smaller at older ages for the time-intensive group, and the motherhood penalty (orange line) is larger.

Figure 3 Parental gender gap in earnings (= motherhood penalty + price of being female – fatherhood premium) by the time intensity of the starting occupation for college graduates

A) Time-intensive occupations

B) Non-time-intensive occupations

Source: Goldin et al. (2022), table 5.

Notes: Of the original NLSY79 sample (1,260 individuals, parents and non-parents), 1,207 have non-missing time-intensive occupations at an early age (and before the first birth, of which 828 were in not time intensive and 379 were in a time-intensive occupations). Time-intensive occupations and not time-intensive occupations are determined by the average share of workers with 45+ hours per week in these occupations in the 1990 Census and the average of five normalized characteristics from O*NET (Goldin 2014). The procedure is described in Goldin et al. (2022), Appendix 3. These estimates use the results from the individual fixed effects estimation with log(hours), log(weeks), previous five year’s work experience, and advanced degrees (for the college graduate sample) as in Goldin, et al. (2022), table 3a col. (5).

Men with time-intensive occupations when younger were enabled or motivated to work even harder when they had children than were men who were not fathers. Extra effort exerted when younger appears to have been disproportionately rewarded through career opportunities that produced higher earnings later. But mothers who began in time-intensive occupations do far worse than non-mothers in these occupations from age 40. One reason for these differences is that interruptions and lower hours at the start of employment are more heavily penalised in time-intensive jobs.

Summary

We began with the notion that life is an adventure. Parenthood is part of the journey when mothers reduce their hours of work, occasionally leave employment for some time, or shift into less time-intensive jobs and firms. But there is a moment when childcare demands greatly lessen and women can increase their hours of paid work and assume greater career challenges. We can think of that moment, metaphorically, as when mothers reach a summit and can then run down the other side of the mountain. But even though they increase their hours of work, they never enter the rich valley of gender equality. In large measure, their inability to earn the same as fathers is due to the positive relationship that children have with the earnings of men and their negative relationship with women’s, even given years of job market experience.

Acknowledgments: This column reflects work under grants from the Russell Sage Foundation (Grant #85-18-05) and the National Science Foundation (Grant #1823635).

References

Angelov, N, P Johansson and E Lindahl (2016), “Parenthood and the Gender Gap in Pay”, Journal of Labor Economics 34(3): 545-79.

Budig, M J (2014), The Fatherhood Bonus and the Motherhood Penalty: Parenthood and the Gender Gap in Pay, Third Way, Next Report.

Goldin, C (2014), “A Grand Gender Convergence: Its Last Chapter”, American Economic Review 104(4): 1091-119.

Goldin, C and J Mitchell (2017), “The New Lifecycle of Women’s Employment: Disappearing Humps, Sagging Middles, Expanding Tops”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 161-82.

Goldin, C, S P Kerr, SP and C Olivetti, C (2022), “When the Kids Grow Up: Women’s Employment and Earnings across the Family Cycle”, NBER Working Paper 30323.

Juhn, C and K McCue (2017), “Specialization Then and Now: Marriage, Children, and the Gender Earnings Gap across Cohorts”, Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 183-204.

Killewald, A (2013), “A Reconsideration of the Fatherhood Premium: Marriage, Co-residence, Biology, and Fathers’ Wages”, American Sociological Review 78: 96-116.

Kleven, H, C Landais, J Posch, A Steinhauer and J Zweimüller (2019),“Child Penalties across Countries: Evidence and Explanation”, AEA Papers and Proceedings 109(May): 122-26 (summarised on Vox column here).

Kleven, H, C Landais, and JE Søgaard (2019), “Children and Gender Inequality: Evidence from Denmark”, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 11(4): 181-209 (summarised on Vox here)

Korenman, S and D Neumark (1991), “Does Marriage Really Make Men More Productive?”, Journal of Human Resources 26(2): 282-307.

Kuziemko, I, J Pan, J Shen and E Washington (2018; revised 2020), “The Mommy Effect: Do Women Anticipate the Employment Effects of Motherhood”, NBER Working Paper 24740 (summarised on Vox here).

Lundberg, S and E Rose (2000), “Parenthood and the Earnings of Married Men and Women”, Labour Economics 7: 689-710.

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics (2019), National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1979 (NLSY79) cohort, 1979-2016 (rounds 1-27). Produced and distributed by the Center for Human Resource Research (CHRR), Ohio State University (sample design information available here).