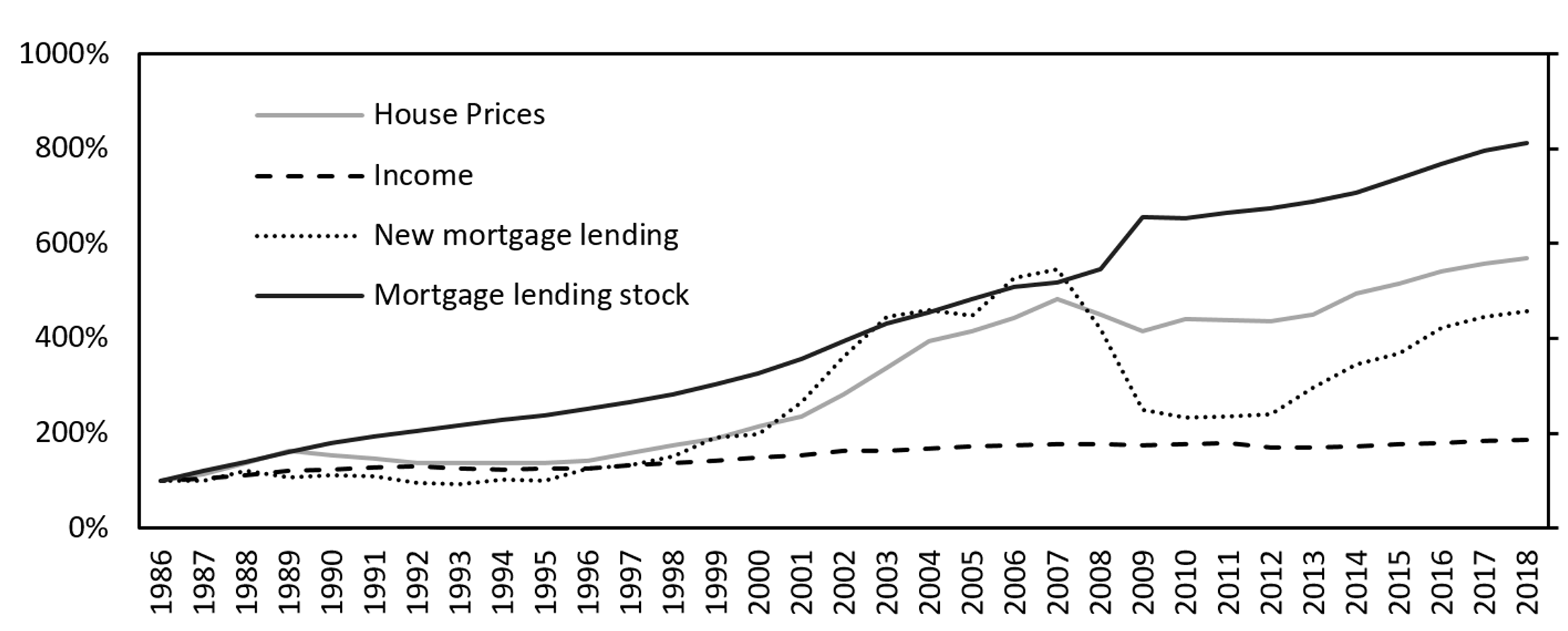

It is well understood that real estate lending booms can cause financial crises and weak recoveries (Schularick et al. 2014). Raising house prices that go hand-in-glove with soaring mortgage borrowing should, therefore, be seen as a cause of concern. Taking the UK as a case in point, Figure 1 shows how over the past three decades, house prices and mortgage debt have risen much faster than income. Two important channels have been established in the literature to explain the positive relationship between house prices and mortgage borrowing. First, if house prices increase, owners want to borrow more to convert the increase in wealth into an increase in consumption (Mian and Sufi 2011). This is the wealth channel, which applies mainly to homeowners but not first-time buyers. Second, if house prices increase, households can borrow more since the value of their collateral has increased, making borrowing cheaper and easier to obtain (Campbell and Cocco, 2007). This is the credit constraint channel, which applies to both homeowners and first-time buyers.

In a recent paper, we show that if house prices increase, deposit-constrained buyers need to borrow more if they cannot easily downsize to a smaller home (Ahlfeldt et al. 2024). We label this effect of house prices on mortgage demand the housing consumption channel, and it applies to all buyers. While intuitive to many (would-be) homebuyers, this channel is not consistent with standard economic models in which, when house prices go up, homebuyers choose proportionately smaller houses to keep housing expenditure constant.

Figure 1 Evolution of house prices, income, and mortgage lending in the UK

Quantifying the housing consumption channel in mortgage demand

Naturally, changes in mortgage borrowing observed in data are shaped by all of the abovementioned channels. To disentangle the different channels, we estimate the system of mortgage demand and supply equations using a unique dataset. We combine transaction prices from the UK Land Registry with data on the mortgage value, interest rates, and borrower age and income at the time of the transaction, covering all UK mortgage issuances from 2005 to 2017. Our estimates show that the elasticity of mortgage demand in response to house prices is positive and relatively high, at 0.82. This means that for every 1% increase in house prices, mortgage demand rises by 0.82%. This suggests that housing and non-housing consumption are less easily substitutable than standard economic models assume, where households are expected to downsize to more affordable homes without significantly increasing borrowing.

We incorporate our estimates of the elasticity of mortgage demand with respect to house prices into a broader economic model where the housing and mortgage markets interact. Intuitively, when house prices rise – perhaps due to increasing demand not met by sufficient new supply – households seek larger mortgages. Similarly, when borrowing increases – for instance, due to lower interest rates or more competition between banks (Szumilo 2021) – housing demand grows as households can finance purchases at higher prices. This creates a feedback loop whereby rising house prices are amplified through the mortgage market.

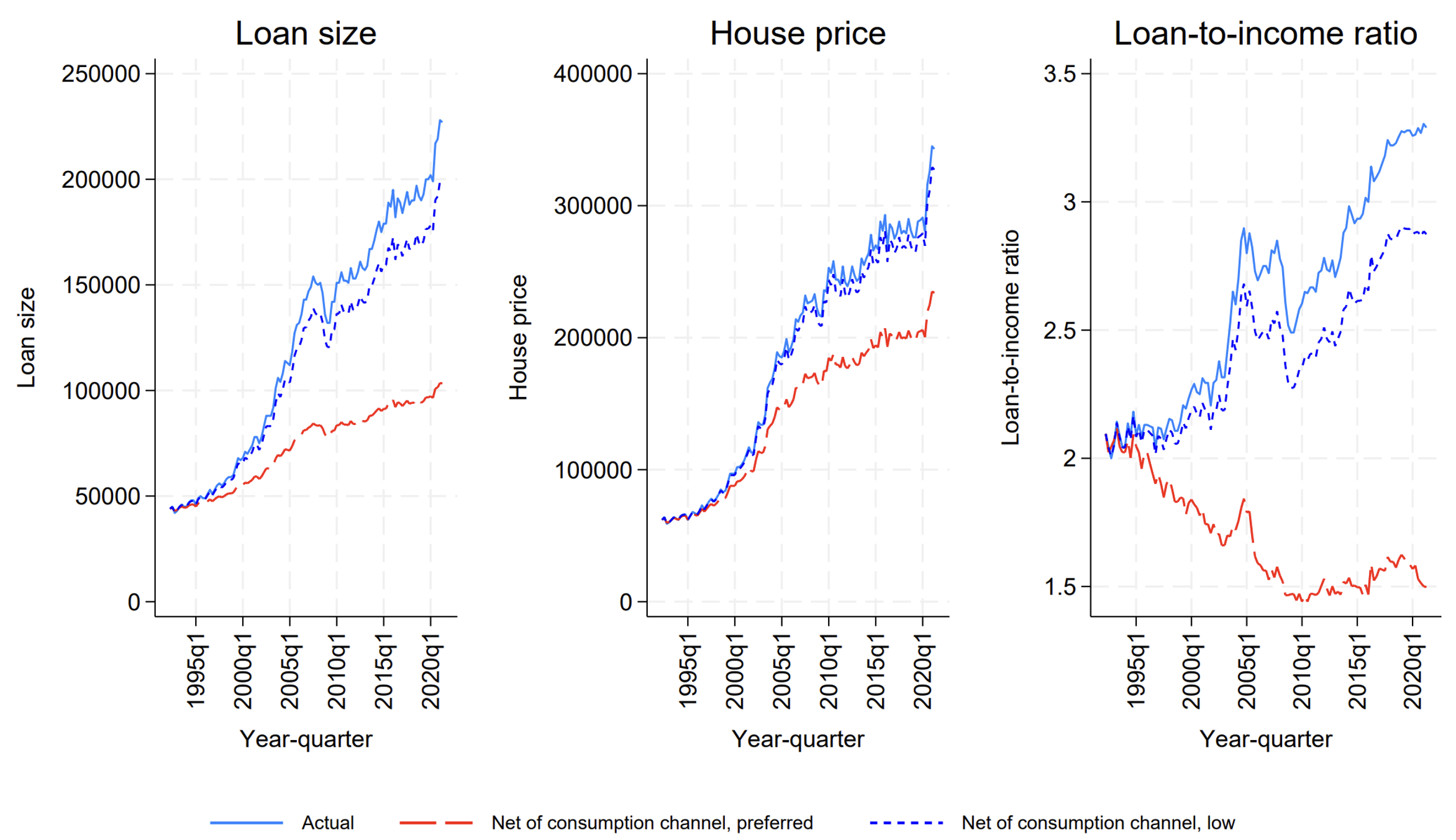

We calibrate this model to fit trends in average house prices and mortgage loan sizes in the UK since 1995. Then, we simulate how house prices and loan sizes would have evolved if the elasticity of mortgage demand with respect to house prices were zero. In this hypothetical scenario in which there is no housing consumption channel, households respond to rising prices by downsizing instead of borrowing more, as assumed in standard models. Our results, illustrated in Figure 2, suggest that without the housing consumption channel, mortgage borrowing in the UK would be 50% lower than observed. House prices themselves would be 31% lower due to the absence of the feedback loop in this hypothetical scenario. Therefore, the housing consumption channel is not only intuitive but also quantitatively important.

Figure 2 Counterfactual trends net of consumption channel

Notes: The solid lines present the actual trends observed in data. The dashed lines give counterfactual outcomes in the absence of a consumption channel: the dashed red line corresponds to no consumption channel, the dashed blue line corresponds to a weaker consumption channel than we observe in the data.

Takeaways for policy

The size of the housing consumption channel we describe in our paper has significant implications for economic vulnerability and housing market cycles. The new results covered in this column strengthen the case for macroprudential regulation of mortgage debt (Ning and Dagher 2012, Kuhn et al. 2020). During periods of strong house price growth, a household will seek a larger mortgage, which, without macroprudential interventions such as limits on high loan-to-income or loan-to-value mortgages, will increase the amount of mortgage debt in the economy directly in response to house price increases.

The housing consumption channel offers a critical insight into the dynamics of the housing market and its broader economic implications. As house prices continue to rise, understanding this channel is essential for policymakers, real estate professionals, and financial planners. The challenge lies in balancing homeownership aspirations with financial stability to avoid a cycle of unsustainable debt. Our study adds to our understanding of the feedback loop between house prices and household leverage and emphasises the role of the housing consumption channel in driving this loop (in addition to the wealth and credit constraint channels).

Authors’ note: Any views expressed are solely those of the authors and should not be taken to represent (or reported as representing) the opinions of the Bank of England or any of its policy committees.

References

Ahlfeldt, G, N Szumilo and J Tripathy (2024), “Housing-Consumption Channel of Mortgage Demand”, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 19370.

Campbell, J and J Cocco, (2007), “How do house prices affect consumption? Evidence from micro data,” Journal of Monetary Economics 54(3): 591–621.

Mian, A and A Sufi (2011), “House Prices, Home Equity-Based Borrowing , and the US Household Leverage Crisis”, American Economic Review 101(5): 2132–2156.

Ning, F and J Dagher (2012), “Lender regulation and the mortgage crisis”, VoxEU.org, 26 June.

Kuhn, M, M Schularick and A Bartscher (2020), “Inequality and US household debt: Modigliani meets Minsky”, VoxEU.org, 18 May.

Primiceri, G, A Tambalotti, and A Justiniano (2017), “The mortgage rate conundrum”, VoxEU.org, 31 October.

Schularick, M, A Taylor, and Ò Jordà (2014), “The great mortgaging”, VoxEU.org, 12 October.

Szumilo, N (2021), “New mortgage lenders and the housing market”, Review of Finance 25(4): 1299-1336.