Major geopolitical challenges have led to a significant increase in the use of economic sanctions, and the recent trend extends far beyond the number of cases during the Cold War era (e.g. van Bergeijk 2022, Yotov et al. 2020).

The sanctions imposed by Western nations on Russia following its invasion of Ukraine mark another milestone, with unprecedented and extensive restrictions placed on trade and financial activities.

There are two notable distinctions of the sanctions against Russia. First, they represent a shift from blanket bans to targeted restrictions on specific agents, entities, sectors, and goods.

This reflects the distinction on the decision between how much to trade or whether to trade at all, at individual good or asset level, and/or with individual entities. Second, Russia is a sizeable economy, and a major producer of gas and oil in particular.

Its deep integration into global value chains until its invasion of Ukraine highlights the importance of international interdependence as a determinant of the effects of sanctions, and the potential for them to have unintended consequences also on the countries that impose them.

Against this background, a modern assessment of the impact of sanctions calls for a new framework that would account for these key distinctions, and we offer our answer to this call in Ghironi et al. (2024a). Simulations from our framework demonstrate that sanctions can hurt the targeted country regardless of whether the exchange rate appreciates or depreciates. They can hurt the targeted country even when imports and exports are rerouted to third countries.

A framework for modelling international economic sanctions

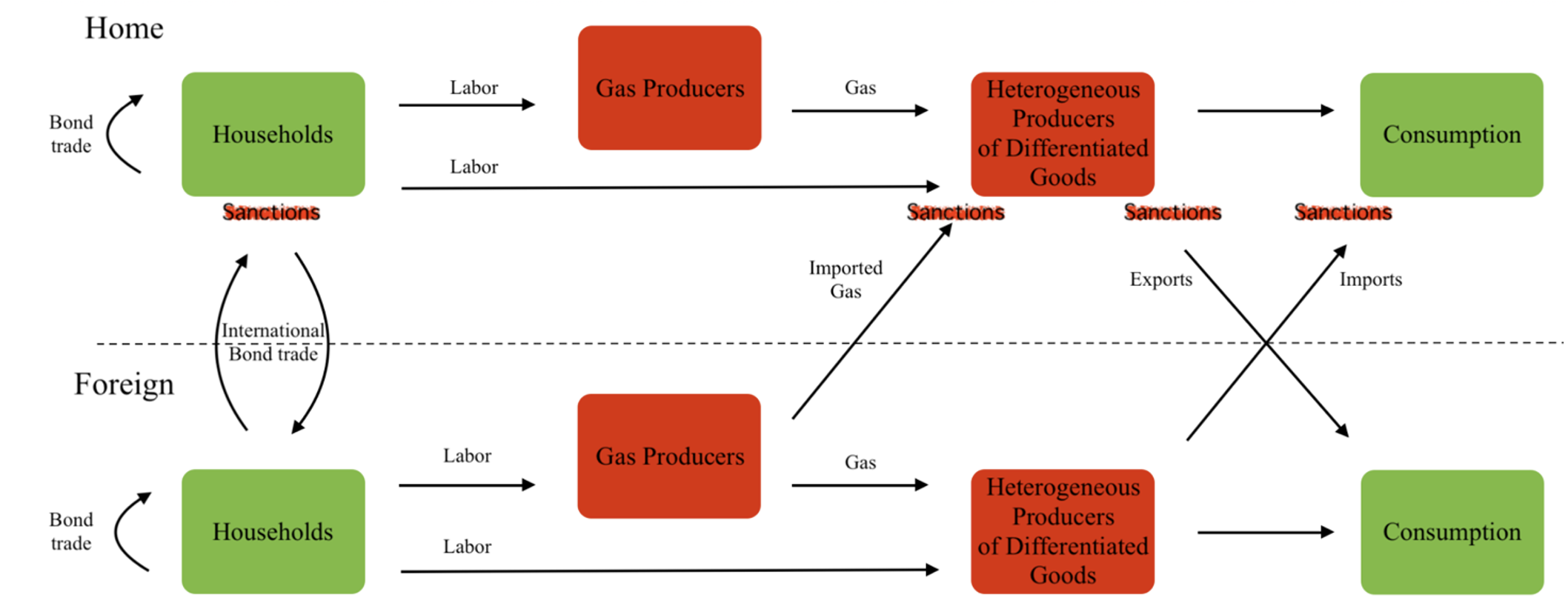

We develop a framework of international trade and macroeconomic dynamics triggered by sanctions that prohibit trade in certain goods and/or to certain agents. Our framework considers a world economy that consists of asymmetric, large countries, and it divides production between an upstream and a downstream sector. The former produces a homogenous commodity (e.g. gas) under perfect competition, and the latter produces differentiated consumption goods under monopolistic competition between heterogeneous firms. We assume country asymmetry by allowing one country to have comparative advantage in production of energy, while the other(s) have comparative advantage in production of consumption goods (Figure 1 summarises the basic structure of the model and its flows of goods, assets, and factors of production).

Figure 1 Model architecture

We consider two types of sanctions: trade sanctions and financial sanctions. Both imply exclusion of certain goods or agents from the international market. Financial sanctions prohibit access to international bond markets for a targeted group of sanctioned individuals. Trade sanctions, on the other hand, prohibit trade in selected individual goods, including gas (Figure 1 highlights where sanctions apply).

How do sanctions work? What are their effects on the sanctioned and the sanctioning countries?

Media reports often rely on exchange rate fluctuations to gauge how sanctions are working.

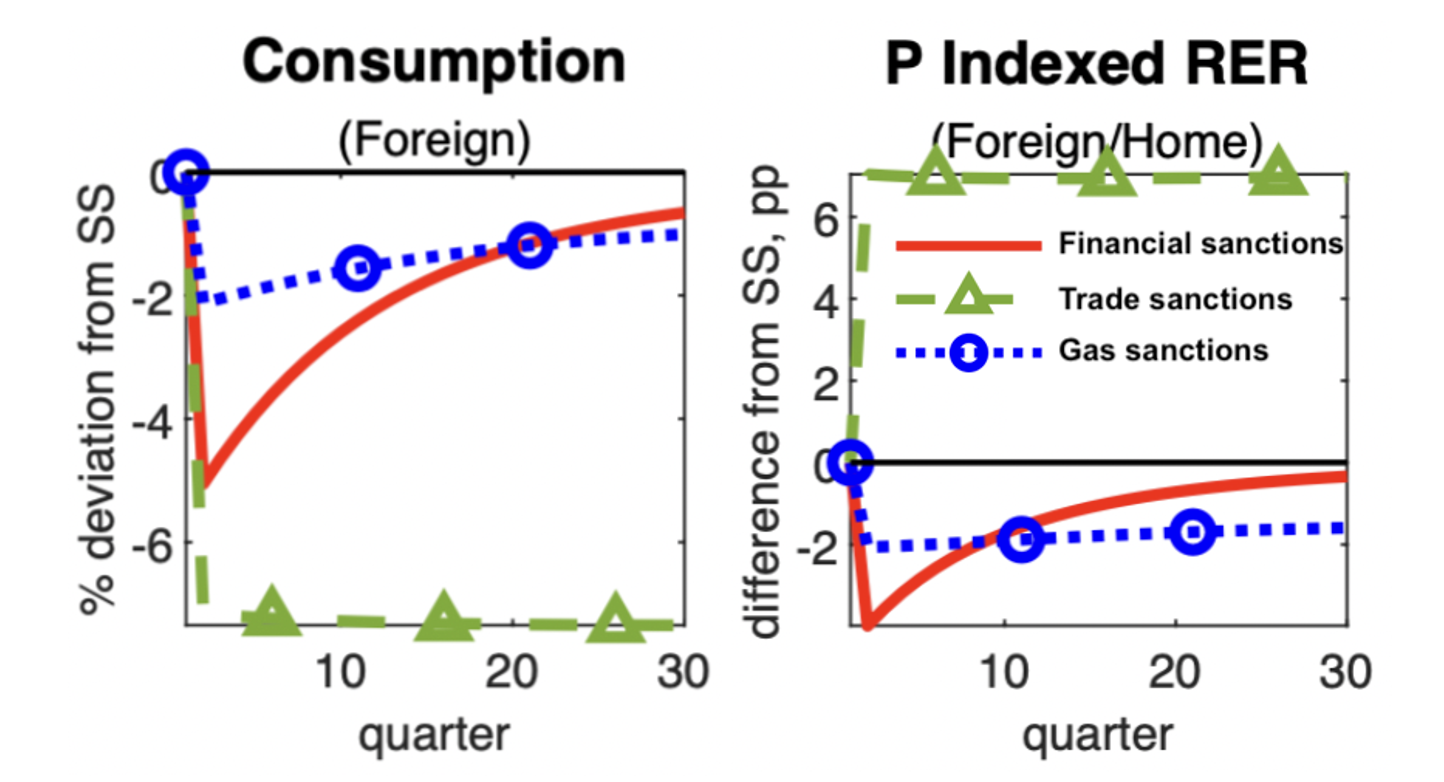

The results of our framework suggest that early concerns about how sanctions are working can be misleading. Simulation exercises involving goods trade, gas trade, and financial sanctions indicate that all types of sanctions may lead to a significant fall in consumption and a sharp increase in labour supply in the sanctioned economy (referred to as “Foreign” in our paper, “Home” being the country that imposes the sanctions). These changes in Foreign consumption and labour supply translate into a pronounced decline in welfare. However, the real exchange rate reacts differently to different types of sanctions. As shown in Figure 2, the combined effect of import and export sanctions (in the form of excluding the products of the top 1% productive firms from international trade) generate depreciation of the sanctioned economy’s exchange rate, while financial sanctions and gas sanctions cause it to appreciate. These findings confirm the finding in Eichengreen et al. (2022), Lorenzoni and Werning (2023), and Itskhoki and Mukhin (2023) that exchange rates are not a good metric to evaluate how sanctions are working.

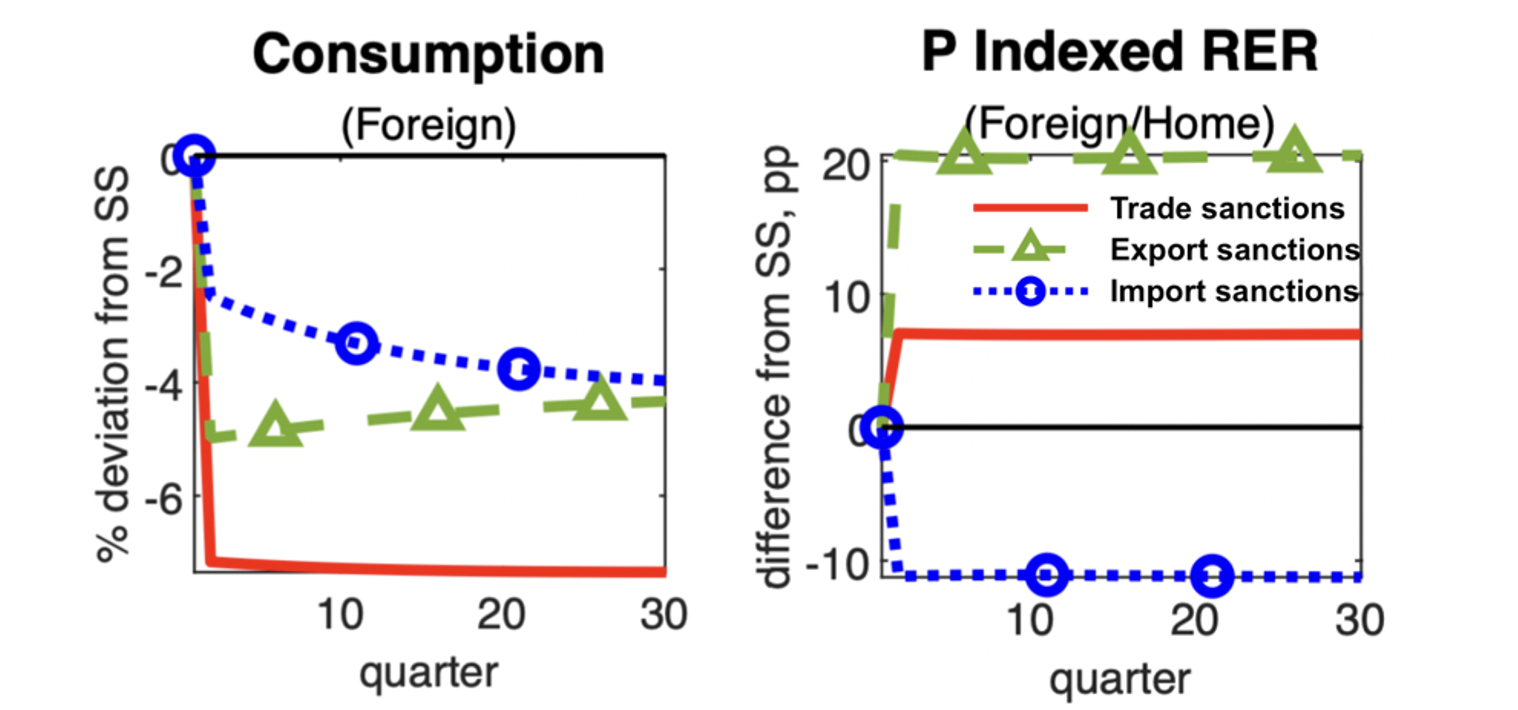

What drives exchange rate fluctuations in response to sanctions? Contrasting from the papers above, our framework links movements in the exchange rate to changes in relative downstream-sector labour costs, average exporter productivity, and consumption composition across countries. Sanctions are most directly tied to the changes in average exporter productivity and consumption composition. For example, following export sanctions that prohibit the most productive Home firms from exporting to Foreign, average import prices in this economy increase because highest productivity Home exporters are those who charge the lowest prices. Moreover, Foreign consumers substitute the goods they no longer have access to with imports of other goods and consumption of domestic goods. Substitution toward imports of other goods induces less productive Home firms, which charge higher prices, to enter the export market. Substitution toward domestic goods includes domestic non-traded goods, also charging higher prices. All these effects put upward pressure on the Foreign consumption price index, causing Home’s real exchange rate to depreciate, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 2 Comparison of financial, trade-in-goods, and gas sanctions

Notes: Lines indicate transitional paths from no-sanction steady state to sanction steady state. Financial sanctions are exclusion of 90% of Foreign households from international bond trade. Trade sanctions are combined effect of import and export sanctions that are introduced with the exclusion of products of the top 1% Home and Foreign productive firms from international trade. Gas sanctions are a ban on gas trade. A negative deviation of the real exchange rate (RER) from the initial point indicates Home RER appreciation whereas a positive deviation indicates depreciation.

Who is most hurt by the sanctions – the sanctioned or the sanctioning country? A quantitative assessment within our framework shows that sanctions reduce welfare for both economies, but more so for the sanctioned country.

Sanctions have a great impact when less advantageous sectors are targeted and the sanctioned economy must move resources into these sectors. In our model, sanctions that prohibit trade in final consumption goods lead to the most reshuffling between heterogenous producers in the final production sector of the sanctioned economy and affects more the welfare of its population. We show that, for financial sanctions to reduce welfare, the fraction of Foreign agents excluded from international bond trading must be very high. Otherwise, non-sanctioned agents end up engaging in international financial transactions also on behalf of the sanctioned ones, largely undoing the aggregate impact of the sanction.

Figure 3 Comparison of export and import sanctions on goods

Notes: Lines indicate transitional paths from no-sanction steady state to sanction steady state. Import and export sanctions are exclusion of products of the top 1% productive firms from international trade. Trade sanctions indicate the combined effect of import and export sanctions. A negative deviation of the real exchange rate (RER) from the initial point indicates Home RER appreciation whereas a positive deviation indicates depreciation.

International economic sanctions and third-country effects

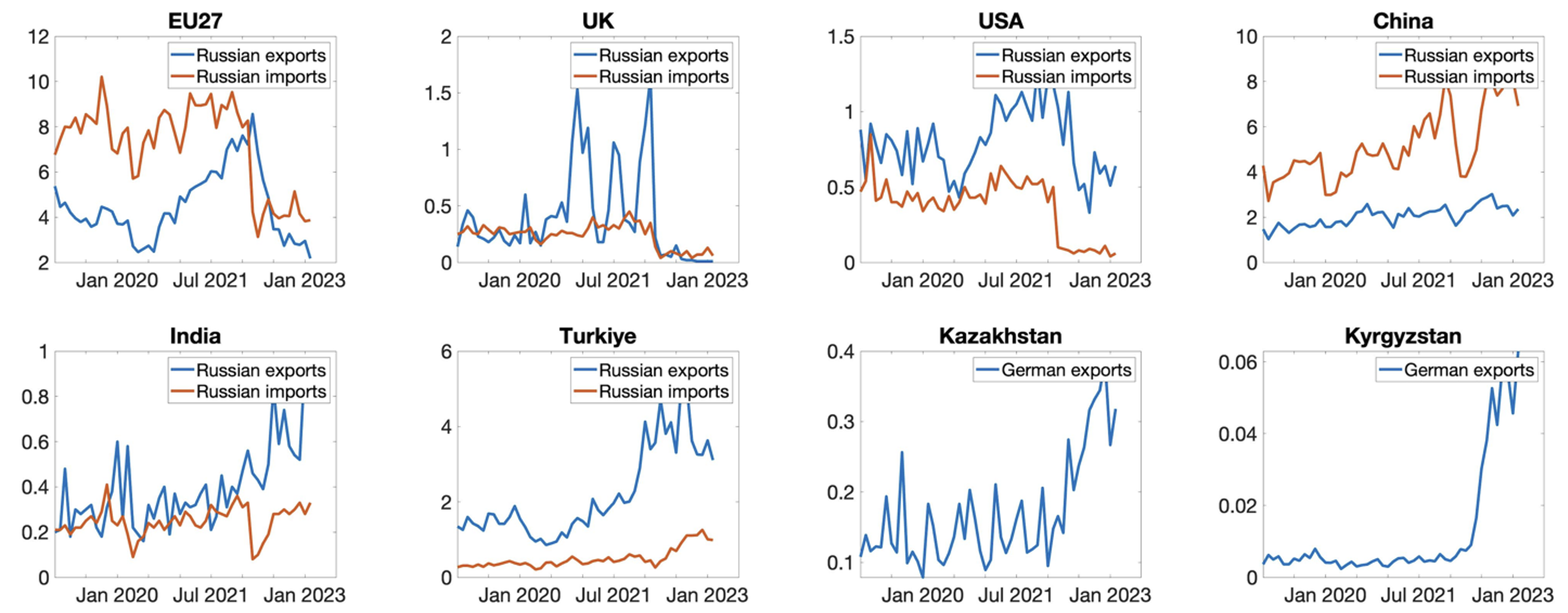

It is often argued that the efficacy of sanctions is limited because they cannot be effectively enforced in an interconnected world due to trade substitution to third countries. This observation was first raised by Friedman (1980) during the Cold War. Results from our other research (Ghironi et al. 2024b) suggest that sanctions still generate substantial welfare losses in the sanctioned economy even in an interconnected three-region world economy.

Overall, sanctions generate inefficient resource allocation and associated welfare losses in the sanctioned economy regardless of exchange rate movements and after consideration of third-country effects. The sanctioned economy must reallocate resources toward sectors in which it is at a disadvantage. If the channels to trade with third countries are difficult to find, sanctions have more significant impact in the sanctioned economy, in terms of economic performance and welfare. Our results also show absent mechanisms that incentivize third countries to join sanctions, they may be better off remaining outside, hence the difficulty of international coordination when imposing sanctions.

Figure 4 Russia’s exports and imports of goods other than mineral fuels and German exports

Notes: The figure plots Russia’s monthly exports and imports of goods to the selected countries and Germany’s exports to Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan from April 2021 to February 2023. Source: Zsolt Darvas, Luca Lery Mofat, Catarina Martins, and Conor McCafrey’s Russian Foreign Trade Tracker (17 May 2023), Federal Statistical Office Germany (4 July 2024).

Does this rerouting of trade imply that sanctions are ineffective? Not quite. Results from our other research (Ghironi et al. 2024b) show that while coordination between the West and the third countries would inflict more significant harm on the sanctioned economy, unilateral imposition of sanctions by the West still has a substantial impact.

Overall, sanctions hurt the target economy regardless of exchange rate movements and after consideration of third-country effects. However, this does not imply that sanctions cannot be made more impactful. Forcing the sanctioned economy to reallocate resources toward sectors in which it is at a disadvantage and collaborating with third countries could significantly amplify their impact in terms of economic performance and welfare. Importantly, coordination with third countries would make sanctions more effective, but our results also show the difficulty of achieving it, as, absent mechanisms that incentivise them to join a sanctioning coalition, third countries are better off remaining outside.

Authors’ note: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the IMF, its Executive Board, or IMF management.

References

Brooks, R. (2024), “Threats to global economic security: Weak sanctions implementation and high debt,” Brookings, 11 April.

De Luce, D (2022), “Too Big to Sanction? A Large Russian Bank Still Operates Freely Because It Helps Europe Get Russian Gas”, NBC, 18 June.

Eichengreen, B, M M Ferrari, A Mehl, I Vansteenkiste and R. Vicquery (2023), “Sanctions and the Exchange Rate in Time”, VoxEU.org, 5 July.

European Commission (2023), “Economically Critical Goods List”, accessed 15 November 2023.

Friedman, M (1980), “Economic sanctions”, Newsweek, 21 January.

Ghironi, F, D Kim and G K Ozhan (2024a), “International Trade and Macroeconomic Dynamics with Sanctions”, CEPR Discussion Paper 19109.

Ghironi, F, D Kim and G K Ozhan (2024b), “International Economic Sanctions and Third-Country Effects”, IMF Economic Review 72: 611-652.

Government of Canada (2023a), “Canadian Sanctions Related to Ukraine”, accessed 15 November 2023.

Government of Canada (2023b), “Special Economic Measures (Russia) Regulations”, accessed 15 November 2023.

Imbs, J and L Pauwels (2023), “The economic costs of trade sanctions”, VoxEU.org, 10 November.

Itskhoki, O and D Mukhin (2022), “Sanctions and the Exchange Rate”, VoxEU.org, 16 May.

Lorenzoni, G and I Werning (2023), “A Minimalist Model fort he Ruble during the Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” American Economic Review: Insights 5(3): 347-56.

Mulder, N (2022), The Economic Weapon: The Rise of Sanctions as a Tool of Modern War, Yale University Press.

US Department of Commerce (2023), “Common High Priority List”, accessed 15 November 2023.

Van Bergeijk, P A G (2022), “The Second Sanction Wave”, VoxEU.org, 5 January.

Yotov, Y, E Yalcin, A Kirilakha, C Syropoulos and G Felbermayr (2020), “The Global Sanctions Database”, VoxEU.org, 4 August.