The ability to issue debt is an important instrument at the government’s disposal. Sovereign borrowing can help buffer the economy from the impact of adverse macroeconomic shocks, but can also make a country vulnerable to financial distress. The sharp increase in fiscal expenditures and debt issuance during the pandemic period, as well as concerns from the fallout of war, have brought more urgency to understanding how a government can borrow.

Despite a diverse set of investor groups in the sovereign debt market, the academic literature has typically focused upon individual creditor groups in isolation. For example, the sovereign-bank nexus (‘doom loop’) literature focuses on domestic bank investors (e.g. Perez 2014, Bocola 2016, Fahri and Tirole 2018, Chari et al. 2020, Baskaya et al. 2024). Similarly, the emerging market (EM) debt literature tends to focus on the role of foreign banks (e.g. Eaton and Gersovitz 1981, Arellano 2008, Mendoza and Yue 2012, Arellano et al. 2020). A further area focuses on explaining foreign official investors (e.g. Wooldridge 2006, Ghosh et al. 2017, Bianchi and Sosa-Padilla 2024). Nevertheless, these various literatures leave some important questions open. Who are the investors that hold government debt? And does this ownership composition matter? In our recent paper (Fang et al. 2024) we address these questions.

Who holds sovereign debt?

To establish who holds sovereign debt, we assemble a dataset that distinguishes the holders of each country’s sovereign debt into foreign and domestic investors and then into three subgroups within those categories: banks, other ‘non-bank’ private investors, and official creditors consisting largely of central banks.

Assembling these data series provides annual holdings by investor groups for 101 countries over 1990-2018.

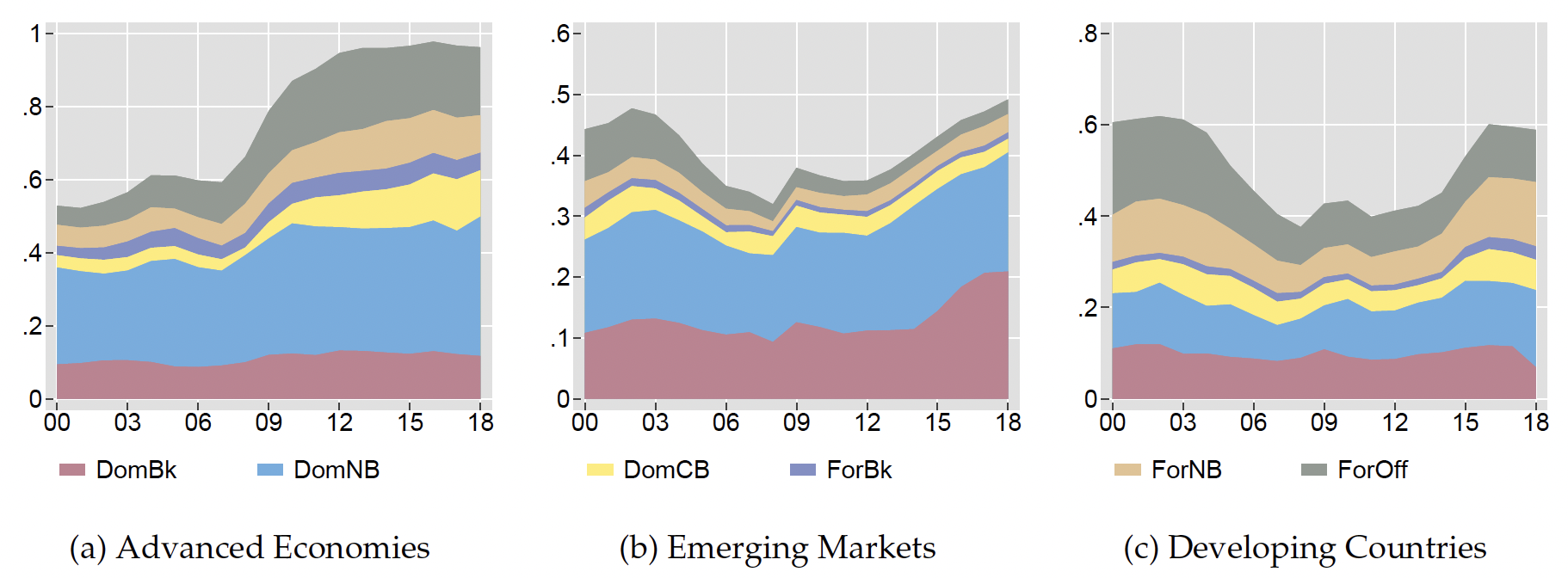

Figure 1 highlights both the growing importance of government debt as well as how the investor base varies in our data set. Panels (a), (b), and (c) show the aggregate investor holdings-to-GDP shares for advanced economy, emerging market and developing economy debt, respectively. These figures show distinctive differences within the groups. For all groups, the foreign bank and non-bank shares have been stable over time. However, Panel (a) of Figure 1 shows that the proportion of foreign official holdings has become larger for advanced economies, as central banks have increased their holdings of safe haven government debt presumably for reserve purposes. Moreover, Panel (b) illustrates how the proportion of foreign official creditor holdings have declined for emerging markets. By contrast, the advanced economy holdings of domestic central banks has expanded over time, tied to the use of unconventional monetary policies and other programmes.

Figure 1 Sovereign debt holdings by investor group

Note: The figures plot the aggregate debt by country group divided by the aggregate GDP of the country group. The investor group holdings are broken down into Domestic Banks (DomBK), Domestic Nonbanks (DomNB), Domestic Central Bank (DomCB), Foreign Banks (ForBK), Foreign NonBanks (ForNB), and Foreign Official (ForOff). Each panel shows a balanced sample over the given time frame.

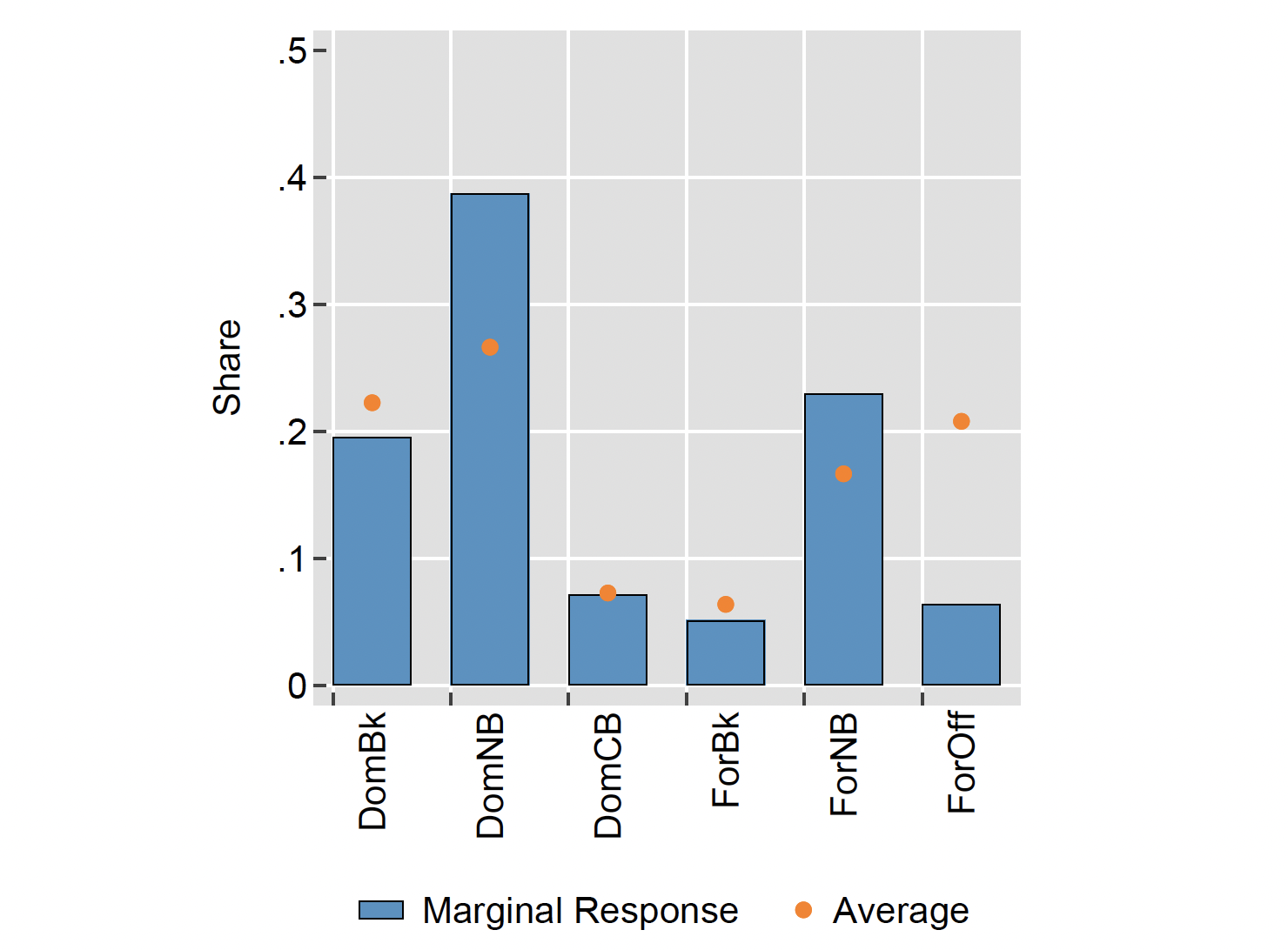

These trends raise an important question. When the size of debt increases, which investors absorb the additional amount? To answer this question, we calculate a measure of the proportional increase in holdings taken up by each investor group when the amount of debt increases. Since we have measures of all investor holdings, this percentage increase in debt must add up to one.

Figure 2 depicts the percentage change across the six investor groups. As the figure shows, domestic non-banks (DomNB) and foreign non-banks (ForNB) take up the highest proportional increase at 39% and 23%, respectively. Importantly, foreign non-banks play a much stronger role in expanding holdings in response to new debt than do foreign banks that take on only 5% on the margin. Moreover, these marginal holdings responses by non- banks are larger than their average holdings shares, given by the orange circle. By contrast, domestic and foreign banks take on less than their average holdings. We find that these patterns are robust to decomposing country groups, splitting subsamples, and evaluating crisis periods.

Figure 2 Marginal holders of sovereign debt

Note: This figure plots the responses of sovereign debt holdings by each investor group to changes in the outstanding amount of sovereign debt as Marginal Response and their average portfolio shares as Average. The groups are Domestic Banks (DomBk), Domestic NonBanks (DomNB), Domestic Central Banks (DomCB), Foreign Banks (ForBk), Foreign NonBanks (ForNB), and Foreign Official (ForOff).

Who are the non-bank investors?

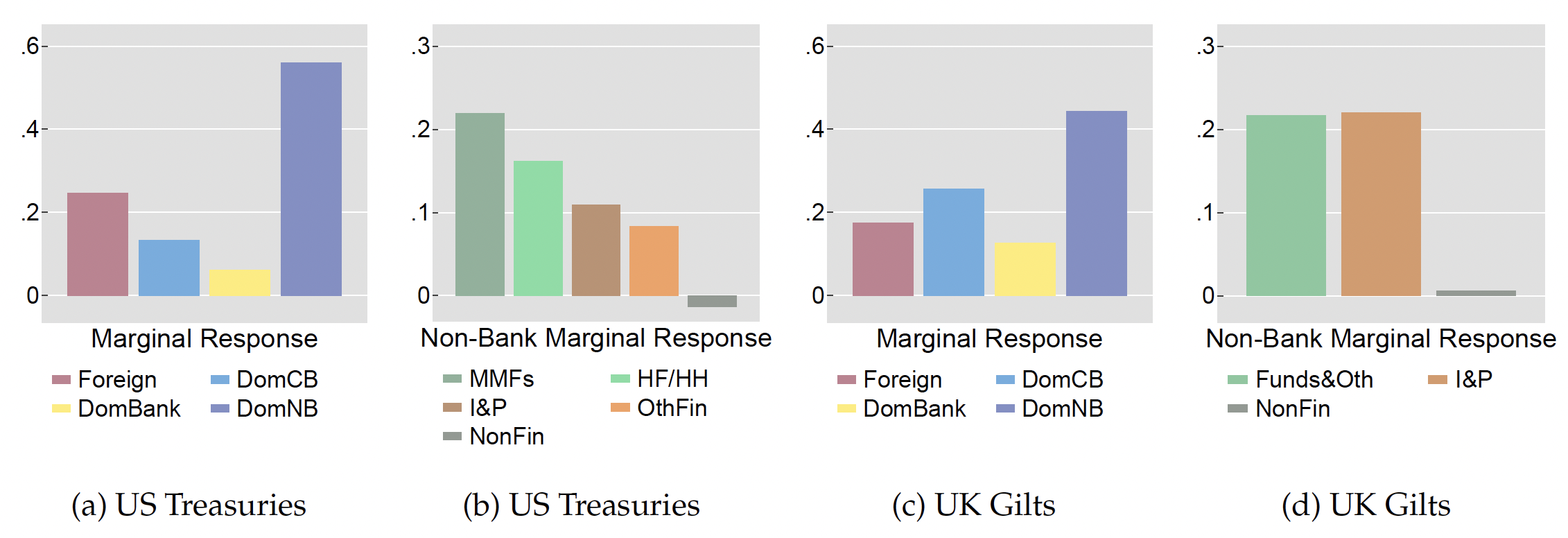

This finding raises the follow-up question: who are these non-bank investors? To shed light on this question, we turn to more disaggregated data sets that provide investor holdings of (i) US Treasuries, (ii) UK gilts, and (iii) euro area securities holdings.

In Figure 3 we use the US and UK data to examine how much debt is taken up on the margin by the domestic non-bank subgroups. As shown for US Treasuries in Panel A, do- mestic non-banks are the primary marginal absorbers of US Treasuries ($0.56 of every dollar issued). But Panel B also shows the share of this response further broken down into sub- groups of: (a) money market funds (MMF), (b) household and hedge funds (HH/HF),

(c) insurance and pension funds (I & P), (d) other financial institutions including investment funds (OthFin), and (e) non-financial corporations (NonFin). These measures show that in- vestment funds are the most important group since money market funds (MMFs) together with hedge funds (HF/HH) correspond to 68% of the pick up of sovereign debt by domestic non-banks.

Figure 3, Panel C shows a similar decomposition for holdings responses of UK gilts but with a different domestic non-bank group into only three categories: (a) investment funds and other similar institutions (Funds & Oth), (b) insurance and pensions (I&P), and (c) non-financial corporations (NonFin). For the UK market, the insurance and pensions sector plays a much larger role for non-bank holdings than found in US Treasuries, accounting for about half of the marginal absorption of the domestic non-bank sector. Funds and other non-bank financial institutions account for the other half.

Figure 3 Domestic non-bank marginal holders: US and UK

Note: This figure plots the responses of sovereign debt holdings by each investor group to changes in the outstanding amount of sovereign debt as Marginal Response and for the non-bank subgroups as Non-Bank Marginal Response. These responses are measured for the holders of US Treasuries and the holders of UK Gilts over 1995q1-2020q4. These responses are shown in panels (a) and (b) for US Treasuries and in panels (c) and (d) for UK Gilt, respectively.

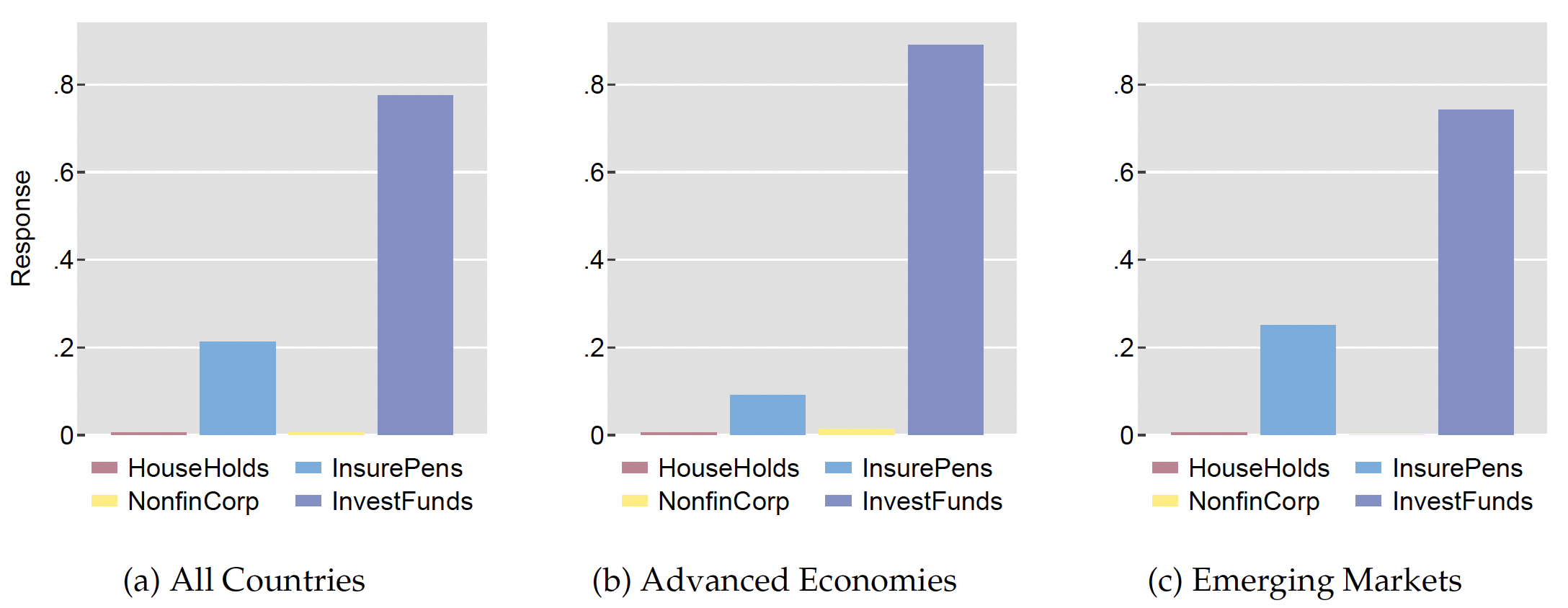

To understand the responses of foreign nonbank groups, we consider holdings by euro area investors of non-euro area government issuers.

As shown in Figure 4, other financial institutions that are largely investment funds represent roughly 80% of the marginal response of variations in holdings of non-euro area holdings regardless of whether broken down into advanced economy or EM issuers. Insurance and pensions are the second most important, but non-financial corporations and households are essentially unresponsive to the outstanding debt variations.

Figure 4 Foreign non-bank marginal holders: Euro area investors

Note: This figure plots the responses of euro area investors to variations in the outstanding amount of non-euro area sovereign debt. Panel (a) shows the responses by investor group to changes in sovereign debt amounts for all countries while Panels (b) and (c) disaggregate these sovereigns into advanced economies versus emerging market issuers.

Why does ownership matter?

We showed above who holds sovereign debt and how the composition of investor holdings varies when that debt expands on the margin. Overall, as debt increases, non-bank investors take up more of this debt than other investor groups. In our paper, we further consider how these investors respond to the price of debt, finding that non-bank investors are also more responsive to reductions in the price of debt. We then ask how much these differences matter to sovereign borrowers, focusing upon EM borrowers.

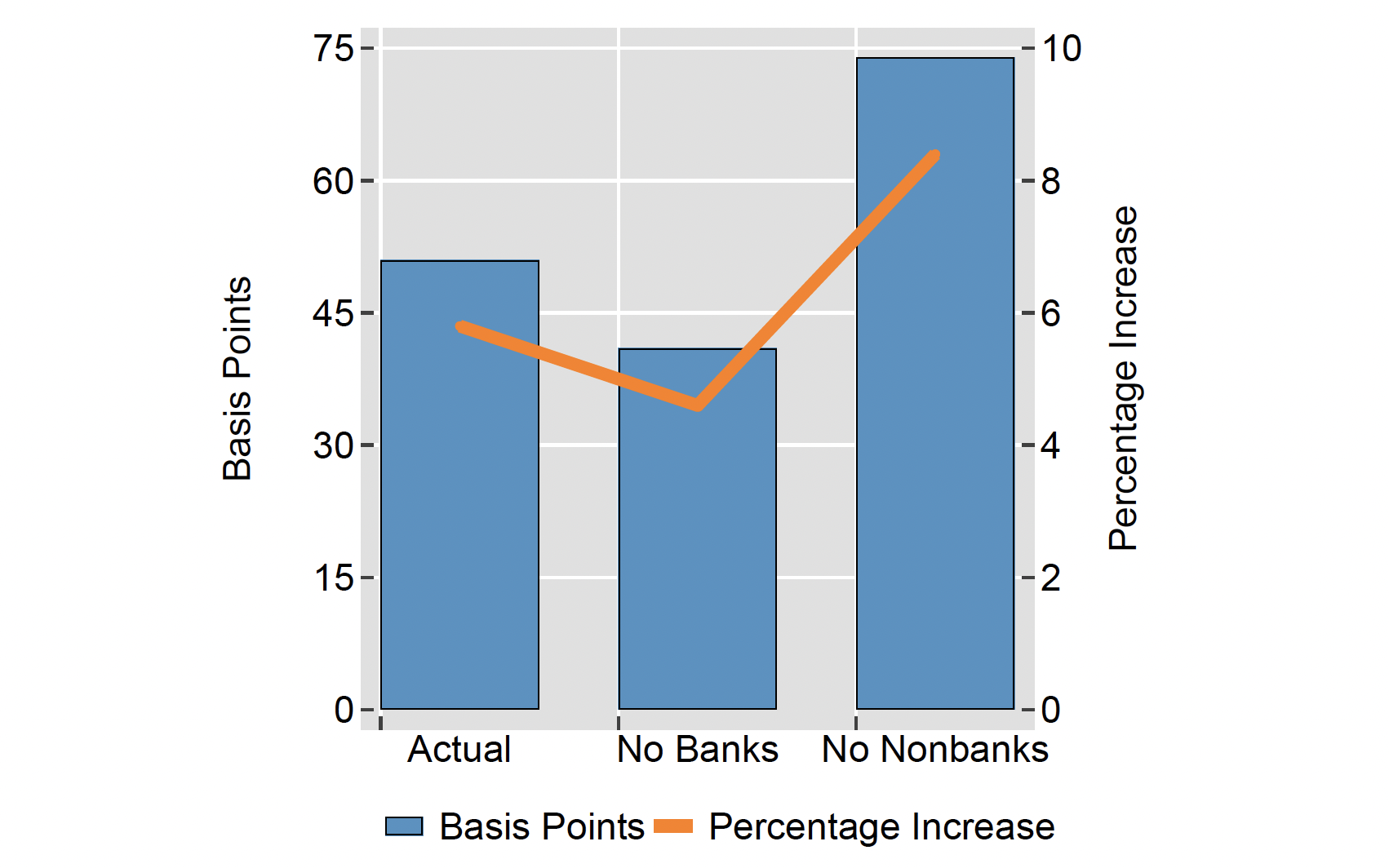

Figure 5 shows the impact on the funding cost of an average EM sovereign in our sample from a hypothetical 10% increase in debt. Based on the ”Actual” ownership composition in the data, the first column shows an increased borrowing cost of 51 basis points or, based upon the average yield for these countries of 8.8%, an increased cost of about 5.8%. Alternatively, the next column shows that if sovereigns only source debt from investors that are not banks (”No Banks”), then the cost impact would be an average 4.6% increase in financing costs. However, if the non-bank investors are not present, as in the last column (”No Nonbanks”), the costs would rise by 74 basis points, reflecting an 8.4% increase. As these measures indicate, EM sovereign borrowers face significant vulnerability to losing non-bank ”investment fund” investors.

Figure 5 Financing costs response to increases in EM sovereign debt

Note: This figure plots the increase in financing costs from a hypothetical 10% increase in government debt in basis points and percentage increase. The percentage increase is based on an average sample yield for emerging markets of 8.8%.

Concluding remarks

The rising levels of government debt worldwide in the wake of the Covid crisis and geopolitical tensions have made answers to questions about their repayment urgent. At the front of those questions is: who holds this debt and does it matter to borrowers in this market? Based upon our analysis, the answers to these questions are striking. First, private financial institutions that are not banks absorb substantially more of the variation in outstanding government debt than other investor groups. Further decomposing this non-bank investment group using country/region-specific data, we find that investment funds are the primary drivers of this larger group. We then identify the propensity to provide funding for EM sovereigns across investor groups and use these to calculate the cost of financing sensitivities to EM sovereign borrowers. These countries face the greatest sensitivity of financing cost against losing non-bank investors compared to any other investment groups. We conclude that EM sovereign investors are highly vulnerable to the presence or absence of non-bank investors. Thus, the behaviour of non-bank investors is crucial for understanding sovereign debt sustainability.

Authors’ note: The views expressed here are those of the authors and not necessarily those of the Bank for International Settlements.

References

Arellano, C (2008), “Default risk and income fluctuations in emerging economies,” American Economic Review.

Arellano, C, Y Bai and G P Mihalache (2020), Monetary policy and sovereign risk in emerging economies (nk-default), Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Arslanalp, S and T Tsuda (2012), “Tracking global demand for advanced economy sovereign debt,” IMF Working Paper No. 12/284.

Arslanalp, S. and T Tsuda (2014), “Tracking global demand for emerging market sovereign debt,” IMF Working Paper No. 14/39.

Baskaya, Y S, B Hardy, Ṣ Kalemli-Özcan and V Yue (2024), “Sovereign risk and bank lending: evidence from the 1999 Turkish earthquake,” Journal of International Economics 150(103918).

Bianchi, J and C Sosa-Padilla (2024), “Reserve accumulation, macroeconomic stabilization, and sovereign risk,” Review of Economic Studies 91(4): 2053-2103.

Bocola, L (2016), “The pass-through of sovereign risk,” Journal of Political Economy 124(4): 879–926. Chari, V V, A Dovis and P J Kehoe (2020), “On the optimality of financial repression,” Journal of Political Economy 128(2): 710–739.

Eaton, J and M Gersovitz (1981), “Debt with potential repudiation: Theoretical and empirical analysis,” Review of Economic Studies 48(2), 289–309.

Fahri, E and J Tirole (2018), “Deadly embrace: Sovereign and financial balance sheets doom loops,” Review of Economic Studies 85(3): 1781–1823.

Faia, E, J Salomao and A V Veghazy (2022), “Granular investors and international bond prices: Scarcity-induced safety,” CEPR Discussion Paper 17454.

Fang, X, B Hardy and K K Lewis (2024), “Who holds sovereign debt and why it matters,” CEPR Discussion Paper 17338.

Ghosh, A, J Ostry and C Tsangarides (2017), “Shifting motives: Explaining the buildup in official reserves in emerging markets since the 1980s,” IMF Economic Review 65: 308–364.

Mendoza, E and V Yue (2012), “A general equilibrium model of sovereign default and business cycles,” Quarterly Journal of Economics 127(2): 889-946.

Perez, D J (2014), “Sovereign debt, domestic banks and the provision of public liquidity,” Stanford Inst. for Economic Policy Research.

Wooldridge, P (2006), “The changing composition of official reserves,” BIS Quarterly Review, September 2006: 25-38.