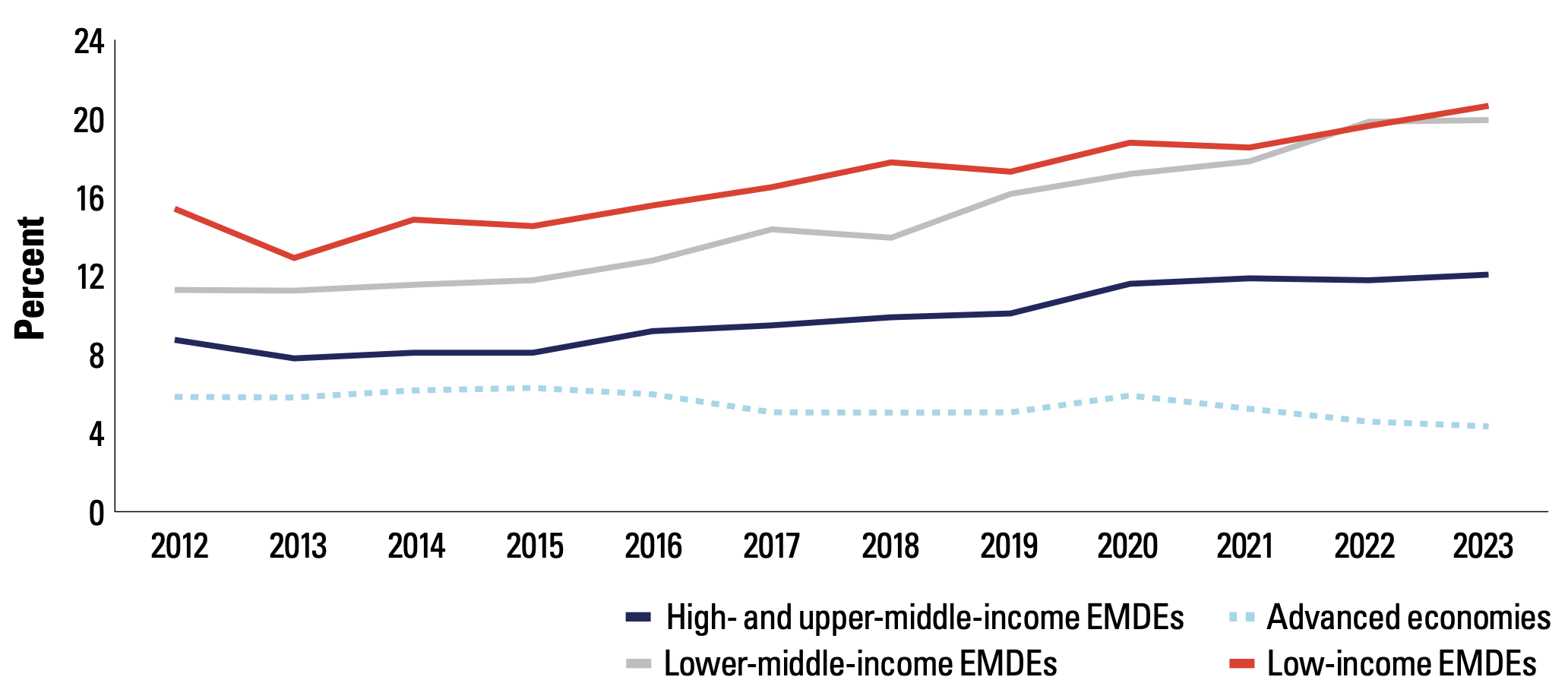

In just 12 years, between 2012 and 2023, the exposure of domestic banks to their government debt rose by over 35% across all emerging market and developing economies (EMDEs). It now stands at a decade high of 16% of bank assets on average, nearly three times higher than in advanced economies (Figure 1). The exposure rose even more – by over 50% – in countries facing public debt distress.

The financial health of the banking sector and the government are often closely linked (Feyen and Zuccardi 2019, Borio et al. 2023). For example, public sector authorities ultimately backstop the financial sector and often play an ownership role in some banks. And by purchasing government bonds, banks help the government meet its funding objectives and promote bond market liquidity.

Figure 1 Government debt to total banking sector assets, 2012–23 (%)

Sources: World Bank staff calculations based on IMF International Financial Statistics data.

This interconnection between banks and the government is known as the sovereign–bank nexus, and at moderate levels it reflects healthy financial sector deepening. Yet the exposure of banks to government debt in EMDEs rose rapidly in recent years as governments borrowed more and encouraged domestic banks to lend to them. The COVID-19 pandemic contributed to this build up, as foreign investors retrenched from local debt markets, while government debt soared to historic highs, going from 49% of GDP in 2019 to almost 55% on average in 2023. Moreover, regulatory standards designed to capture the risks that banks take often do not account for the tail risk of a local currency government debt default, which is significant in some EMDEs, facilitating the accumulation of these exposures.

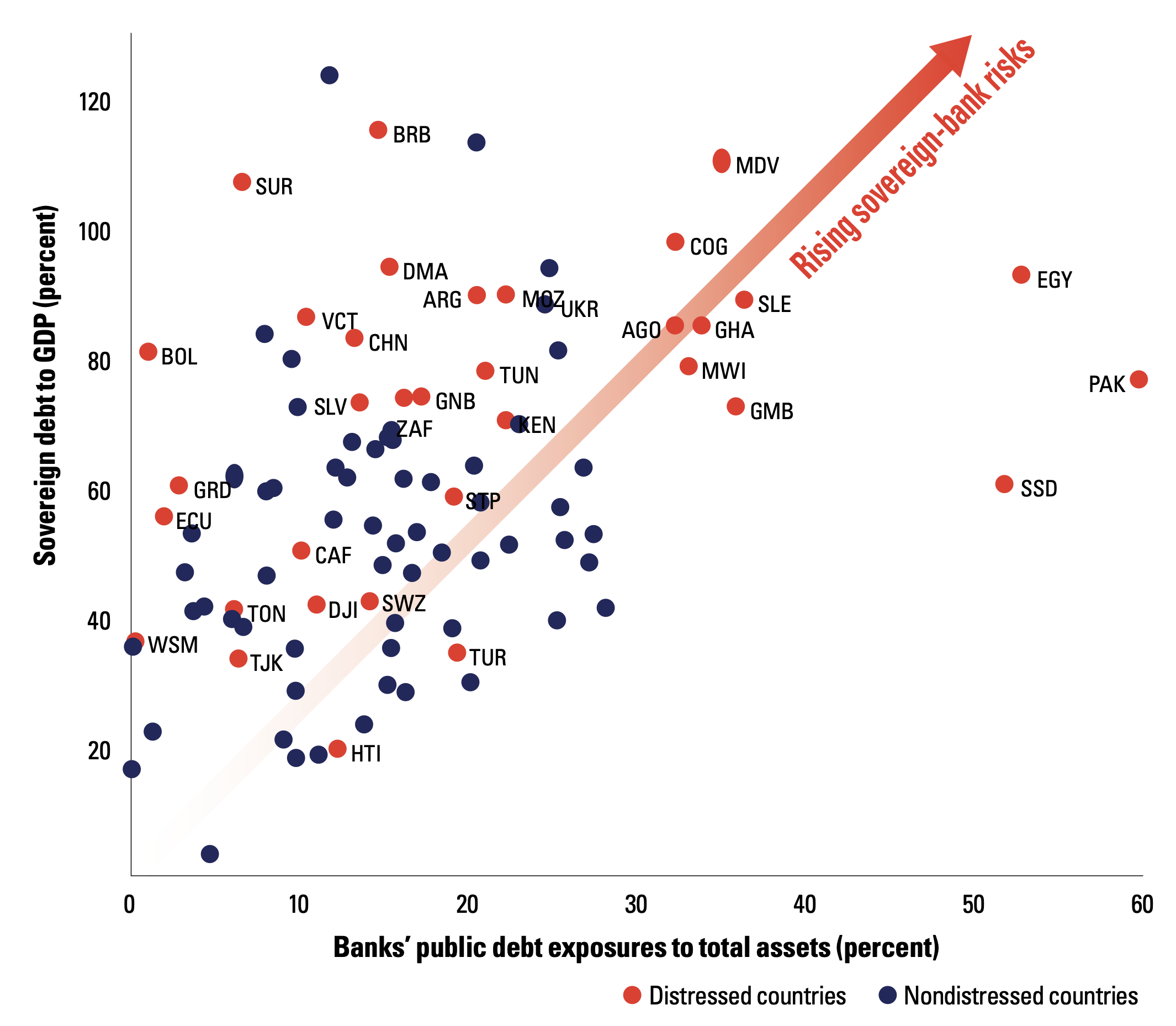

Figure 2 Sovereign debt to GDP and government debt to total banking sector assets in 2023 (%)

Sources: World Bank staff calculations based on IMF International Financial Statistics and WEO data.

The results of this surge in borrowing and lending were twofold: governments became more indebted (the vertical axis in Figure 2) and domestic banks became more exposed to that government debt (the horizontal axis).

Because no government debt is completely risk free (and EMDE government debt often carries much more risk than that of advanced economies) and debt sustainability concerns have been rising recently (Van Trotsenburg and Saavedra 2024), this tighter connection between banks and their governments exposes EMDE financial sectors to additional risks, including government debt restructurings and defaults. This ‘deadly embrace’ between banks and their government is not just an issue in EMDEs, as demonstrated by the Eurozone crisis (Grande and Angelini 2014).

Rising risks

In a recent report (World Bank 2024), we analyse the current state and potential implications of the evolving sovereign–bank nexus in EMDEs and recommend actions for policymakers to mitigate associated risks.

To be sure, the majority of banks in EMDEs have demonstrated resilience in the face of multiple overlapping shocks, and most banks appear to have adequate buffers to withstand future shocks.

However, out of 33 EMDEs in which banks have high government exposure (where government debt is more than 20% of bank assets), 16 countries face high government debt risks. A deterioration of the value of government debt in these countries could threaten macroeconomic and financial sector stability and trigger banking crises. Our analysis indicates that a 5% loss on banks’ government debt holdings – which is relatively small by historical standards – would cause one-fifth of banks in the sample of debt-distressed countries to become undercapitalised.

A particular risk is a joint banking–government debt crisis, with a government default or domestic debt restructuring spilling over to the banking sector and causing bank failures and financial instability (Kaminsky and Reinhart 1999, Cerra and Saxena 2008). Our analysis shows that countries with a high sovereign–bank nexus also tend to be less prepared to deal with financial stress, which can amplify adverse feedback loops.

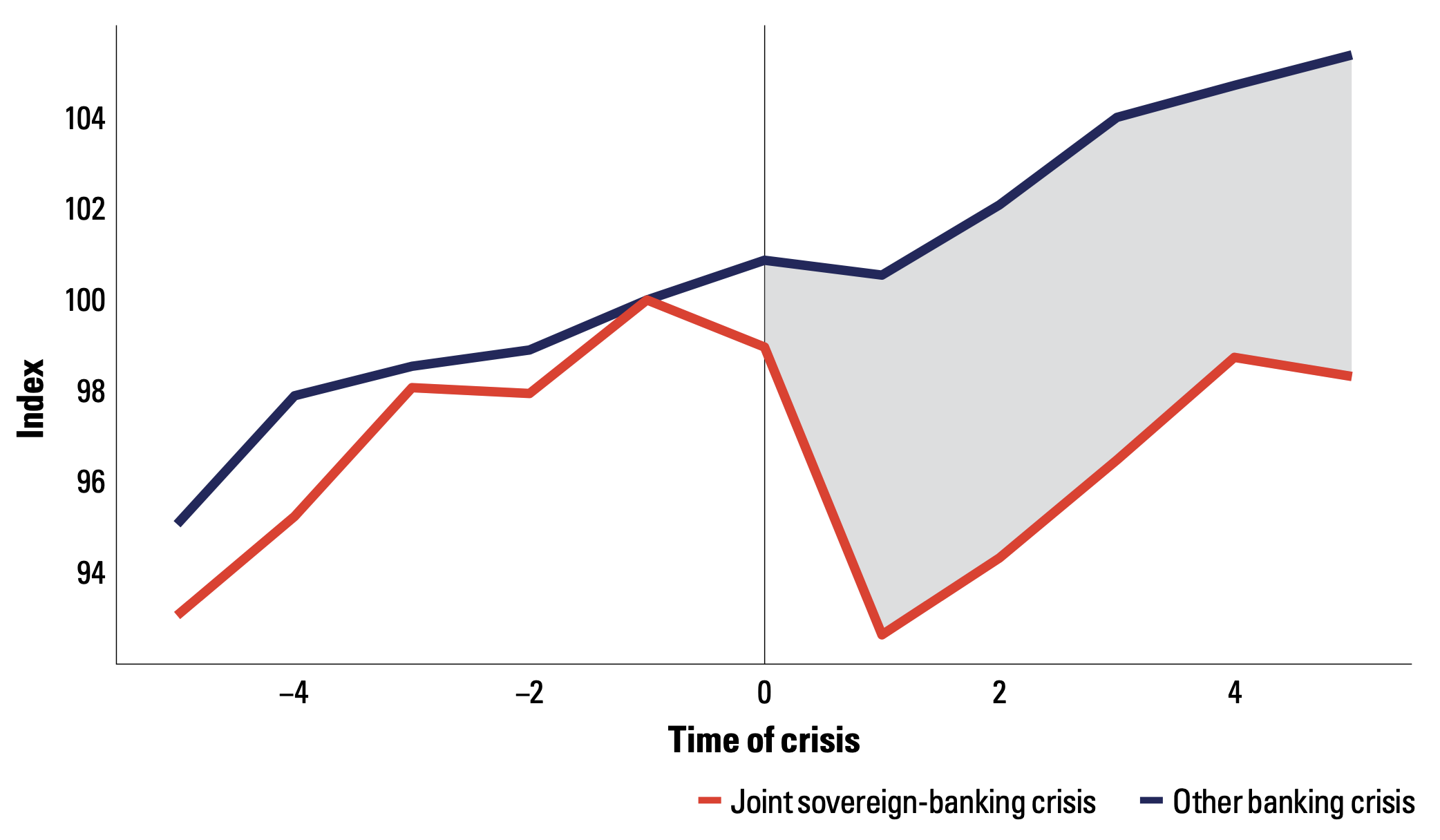

While all banking crises are costly for the government and the broader economy, combined government debt and banking crises have historically been the most severe and are associated declines in median real GDP per capita of 7% one year from their onset, with GDP still considerably lower several years later (Figure 3).

The indirect fallout from joint banking–government debt crises has generally included decreased bank lending, which depresses economic activity and drives unemployment higher, and reduced tax revenues, which impairs government spending and can further increase government debt. History shows that such crises have hit the poorest and most vulnerable parts of the population the hardest.

Figure 3 Median GDP per capita five years before and after a joint public debt and systemic banking crisis event (red) and a banking crisis only (navy) (constant 2015 $, index t–1=100)

Sources: World Bank staff calculation based on Laeven and Valencia (2020) and World Bank World Development Indicators.

Note: The red line shows joint banking and government debt crises that occurred globally between 1970 and 2017. There were 21 cases within a three-year span. The navy line represents other banking crises during that time span. This sample includes 80 crises. The analysis starts from the first year of any crisis occurrence. Both lines show the median GDP per capita in constant 2015 $, indexed to one year before the crisis over an 11-year period (five years before and after the crisis), across the respective crisis samples.

What can be done?

First and foremost, sound fiscal and other policies to preserve public debt sustainability and macroeconomic stability are required. EMDE banking authorities cannot resolve sovereign–bank nexus risks alone, but they can take concrete steps to foster more prudent risk taking by banks and strengthen financial sector resilience. These include:

- Introducing more granular disclosure requirements for banks’ exposures to the government. Banks are required to hold minimum government securities for liquidity management but face no maximum limits and have limited disclosure requirements on such exposures. This renders their balance sheets less transparent and makes it difficult for markets to estimate impacts of various sovereign stress scenarios.

- Carefully considering the benefits and drawbacks of capital charges on government debt exposures in local currency, particularly if these exposures exceed certain thresholds. Currently, these capital charges are zero.

- More broadly, encouraging stronger bank buffers well in advance of potential crises, implementing effective financial safety nets and crisis management frameworks, putting in place appropriate institutional arrangements to allow decision makers to coordinate and act decisively, and conducting regular stress-testing for banks that also consider possible impacts of sovereign debt stress.

- Finally, in the medium term, continuing to promote the deepening of domestic capital markets and the institutional investor base to mitigate the concentration of government bonds in banks’ asset holdings.

References

Borio C, M Farag and F Zampolli (2023), “Tackling the Fiscal Policy-Financial Stability Nexus,” BIS Working Papers 1090.

Cerra, V and S Saxena (2008), “Growth Dynamics: The Myth of Economic Recovery,” American Economic Review 98(1): 439-57.

Feyen, E and I Zuccardi (2019), “The Sovereign-Bank Nexus in EMDEs: What Is It, Is It Rising, and What Are the Policy Implications?”, World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 8950.

Grande, G and P Angelini (2014), “How to loosen the banks-sovereign nexus,” VoxEU.org, April 8.

Kaminsky, L and C Reinhart (1999), “The Twin Crises: The Causes of Banking and Balance-of-Payments Problems,” American Economic Review 89(3): 473–500.

Laeven, L and F Valencia (2020), “Systemic Banking Crises Database: A Timely Update in COVID-19 Times,” CEPR Discussion Paper 14569.

Van Trotsenburg, A and P Saavedra (2024), “Urgent need to address liquidity pressures in developing countries,” World Bank Blogs, World Bank: Washington, DC.

World Bank (2024), “Sovereign-Bank Nexus Risks Need to Be Addressed”, Chapter 2 in Finance and Prosperity 2024, Washington, DC.